1963 Television Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Press Release As PDF File

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS - PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: JULIEN’S AUCTIONS ANNOUNCES PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN Emmy, Grammy and Academy Award Winning Hollywood Legend’s Trademark White Suit Costume, Iconic Arrow through the Head Piece, 1976 Gibson Flying V “Toot Uncommons” Electric Guitar, Props and Costumes from Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, Little Shop of Horrors and More to Dazzle the Auction Stage at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills All of Steve Martin’s Proceeds of the Auction to be Donated to BenefitThe Motion Picture Home in Honor of Roddy McDowall SATURDAY, JULY 18, 2020 Los Angeles, California – (June 23rd, 2020) – Julien’s Auctions, the world-record breaking auction house to the stars, has announced PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN, an exclusive auction event celebrating the distinguished career of the legendary American actor, comedian, writer, playwright, producer, musician, and composer, taking place Saturday, July 18th, 2020 at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills and live online at juliensauctions.com. It was also announced today that all of Steve Martin’s proceeds he receives from the auction will be donated by him to benefit The Motion Picture Home in honor of Roddy McDowall, the late legendary stage, film and television actor and philanthropist for the Motion Picture & Television Fund’s Country House and Hospital. MPTF supports working and retired members of the entertainment community with a safety net of health and social -

200 Bail Posted by Hamerlinck

Eastern Illinois University The Keep February 1988 2-19-1988 Daily Eastern News: February 19, 1988 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1988_feb Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: February 19, 1988" (1988). February. 14. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1988_feb/14 This is brought to you for free and open access by the 1988 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in February by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eastern Illinois University I Charleston, I No. Two�t;ons. Pages Ul 61-920 Vol 73, 104 / 24 200 bail posfour felonies andte each ared punishable by Wednesday. Hamerlinck brakes at the accident scene. "He with a maximum of one to three years Hamerlinck recorded a .18 alcohol (White) had cuts all over and hit his sophomore Timothy in prison. level. Johnson said the automatic head on the windshield. I'm sure a lot of erlinck, who was arrested Wed Novak said a preliminary appearance maximum allowable level is .10. If a the blood loss he suffered was from his ay morning in connection with a hearing has been set for Hamerlinck at person is arrested and presumed to be head injury." and run accident that injured two 8:30 a.m. Feb. 29 in the Coles County intoxicated, they could be charged with Victims of the accident are still .nts, posted $200 bail Thursday Jail's court room. driving under the influence even if attempting to recover both physically oon and was released from the Charleston Police Chief Maurice their blood alcohol level is below .10, and emotionally after they were hit by County JaiL Johnson said police officers in four Johnson added. -

REDEFINING “NERDINESS”: the Big Bang Theory Reconsidered REDEFINING “NERDINESS”: Many Studies Define “Nerdiness” Differently

ARTICLE Title REDEFINING “NERDINESS”: The Big Bang Theory Reconsidered REDEFINING “NERDINESS”: Many studies define “nerdiness” differently. Some textual cues including explicit and implicit cues. These would define gifted students as “nerds” (O’Connor 293), terms are adopted from Culpeper’s The Language and The Big Bang Theory Reconsidered suggesting that the word is based solely on intelligence. Characterisation: People in Plays and Other Texts, in which he Others may define “nerds” as “physical self-loathing [and explains that these textual cues can help a viewer make having] technological mastery” (Eglash 49), suggesting certain inferences about a specific character (Language that “nerds” have body issues or are somehow more and Characterisation 167). Explicit cues are when charac- BY JACLYN GINGRICH technologically savvy than the average person. Bednarek ters specifically express information about themselves or defines “nerdiness” as displaying the following linguistic others (Language of Characterisation 167). An example framework: “believes in his own intelligence,” “was a child would be when Leonard says, “Yeah, I’m a frickin’ genius” ABSTRACT it is that they are average people socializing with each prodigy,” “struggles with social skills,” “is different,” “is health (“The Middle Earth Paradigm”). Here he is explicitly other and living normal lives. The Big Bang Theory displays This paper analyzes the linguistic characteristics of Leonard obsessed/has food issues,” “has an affinity for and knowl- saying that he believes he has intellectual superiority. the comical reality of what normally happens in these Hofstadter, television character from The Big Bang Theory and edge of computer-related activities,” “does not like change,” Implicit cues are implied. -

BILL COSBY Biography

BILL COSBY Biography Bill Cosby is, by any standards, one of the most influential stars in America today. Whether it be through concert appearances or recordings, television or films, commercials or education, Bill Cosby has the ability to touch people’s lives. His humor often centers on the basic cornerstones of our existence, seeking to provide an insight into our roles as parents, children, family members, and men and women. Without resorting to gimmickry or lowbrow humor, Bill Cosby’s comedy has a point of reference and respect for the trappings and traditions of the great American humorists such as Mark Twain, Buster Keaton and Jonathan Winters. The 1984-92 run of The Cosby Show and his books Fatherhood and Time Flies established new benchmarks on how success is measured. His status at the top of the TVQ survey year after year continues to confirm his appeal as one of the most popular personalities in America. For his philanthropic efforts and positive influence as a performer and author, Cosby was honored with a 1998 Kennedy Center Honors Award. In 2002, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor, was the 2009 recipient of the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor and the Marian Anderson Award. The Cosby Show - The 25th Anniversary Commemorative Edition, released by First Look Studios and Carsey-Werner, available in stores or online at www.billcosby.com. The DVD box set of the NBC television hit series is the complete collection of one of the most popular programs in the history of television, garnering 29 Emmy® nominations with six wins, six Golden Globe® nominations with three wins and ten People’s Choice Awards. -

Socioeconomic Class Representation in Sitcoms Awroa:&~

KEEPING UP WITH THE JONESES: SOCIOECONOMIC CLASS REPRESENTATION IN SITCOMS by ALEXANDRA HICKS A THESIS Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2014 A• Abstracto( the Thesis of Alexandra Hicks for 1he degree ofBachelor of Arts in the School of Journalism and Communication to be talcen June, 2014 Title: Keeping Up With the Jonescs: Socioeconomic Class Representation in Sitcoms Awroa:&~ This thesis examines the representation of socioeconomic class in situation comedies. Through the influence of the advertising industiy, situation comedies (sitcoms) have developed a pattem throughout history of misrepresenting ~ial class, which is made evident by their portrayals ofdifferent races, genders, and professions. To rectify the IKk ofprevious studies on modem comedies, this study analyzes socioeconomic class representation on sitcoms that have aired in the last JS years by taking a sample ofseven shows and comparing the estimated cost of characters' residences to the amount of money they would likely earn in their given profession. 1be study showed that modem situation comedies misrepresent socioeconomic class by portraying characters living in residences well beyond what they could afford in real life. Accurate demonstration ofsocioeconomic class on television is imperative be<:ause images presented on television genuinely influence viewers• perceptions of reality. Inaccurate portrayals ofclass could cause audiences to develop distorted views ofmember.; of socioeconomic classes and themselves. u Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Debra Merskin for inspiring me to examine television in an in-depth and critical manner. -

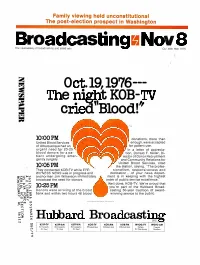

Broadcasting O Ov

Family viewing held unconstitutional The post -election prospect in Washington Broadcasting o The newsweekly of ov broadcasting and allied arts Our 46th Year 1976 Oct.19, 1976--- The night KOB -TV cried Blood!' 10:00 PM donations, more than United Blood Services enough, were accepted of Albuquerque had an for patient use. urgent need fpr 20 -25 In a letter of apprecia- blood donors for a pa- tion, Donald F, Keller, Di- tient undergoing emer- rector of Donor Recruitment gency surgery. and Community Relations for United Blood Services, cited 10:05 PM the station, saying, "The profes- They contacted KOB -TV while EYE- sionalism, responsiveness and WITNESS NEWS was in progress and dedication...of your news depart- anchorman Jim Wilkerson immediately ment is in keeping with the highest broadcast the need for donors. order of public service excellence." Well done, KOB -TV. We're proud that 10:25 PM you're part of the Hubbard Broad- Donors were arriving at the blood casting 50 -year tradition of award - bank and within two hours 46 blood winning service to the public. n-< unneo Bwod Sarwes of aouaue, cue rmDNm Hubbard Broadcasting KSTP -TV KSTP -AM KSTP -FM KOB -TV KOB-AM KOLFM WTOG -TV WGTO -AM Minneapolis. Minneopolis Minneapolis- Albuquerque Albuquerque Albuquerque Tempo. Cypress Sr. Paul St. Paul Sr. Paul St. Pe burp Gardens MagicT stogy. 61 ri:11°1 yPou've probably heard about Greater new leadership by Pulse (Mar -May '7 Media's Magic Music Then: "Sold Out" city! programming by now. Now all's well at Greater Medi, They tell us it's the Right? first brand -new idea in music Well, yes. -

Frons Launches Soap Sensation

et al.: SU Variety II SPECIAL 'GOIN' HOLLYWOOD' EDITION II NEWSPAPER Second Class P.O. Entry Supplement to Syracuse University Magazine CURTIS: IN MINIS Role Credits! "War" Series Is All-Time Screen Dream Syracuse- We couldn't pos sibly get 'em all, but in these 8 By RENEE LEVY series "Winds of War," based on to air in late spring and the entire pages find another 40-plus SU Hollywood- The longest. The Herman Wouk 's epic World War II package will air in Europe next year. alumni getting billboards on most demanding. The hardest. The novels, "War and Remembrance" Curtis, exec producer, director the boulevard. In our research, most expensive. That's the story was shot in 757 locations in 10 and co-scribe of the teleplay, spent we discovered a staggering net behind Dan Curtis 'SO's block countries, using more than 44,000 two years filming and a year and a work of Syracusans in the busi buster miniseries " War and Re actors and extras and nearly 800 half editing "War and Remem ness-producers, directors, membrance," which aired the first sets. The production- the longest brance," a project he originally actors, editors, and more! We 18 of its 30 hours in November on in television history--cost an es considered undoable-particular soon realized that all of them ABC-TV. timated $ 105 million to make. The ly because of the naval battles and would not fit, and to those left A sequel to Curtis's 1983 maxi- concluding 12 hours are expected the depiction of the Holocaust. -

Stand-Up Comedy in Theory, Or, Abjection in America John Limon 6030 Limon / STAND up COMEDY / Sheet 1 of 160

Stand-up Comedy in Theory, or, Abjection in America John Limon Tseng 2000.4.3 18:27 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 1 of 160 Stand-up Comedy in Theory, or, Abjection in America 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 2 of 160 New Americanists A series edited by Donald E. Pease Tseng 2000.4.3 18:27 Tseng 2000.4.3 18:27 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 3 of 160 John Limon Duke University Press Stand-up Comedy in Theory, or, Abjection in America Durham and London 2000 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 4 of 160 The chapter ‘‘Analytic of the Ridiculous’’ is based on an essay that first appeared in Raritan: A Quarterly Review 14, no. 3 (winter 1997). The chapter ‘‘Journey to the End of the Night’’ is based on an essay that first appeared in Jx: A Journal in Culture and Criticism 1, no. 1 (autumn 1996). The chapter ‘‘Nectarines’’ is based on an essay that first appeared in the Yale Journal of Criticism 10, no. 1 (spring 1997). © 2000 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ! Typeset in Melior by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Tseng 2000.4.3 18:27 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 5 of 160 Contents Introduction. Approximations, Apologies, Acknowledgments 1 1. Inrage: A Lenny Bruce Joke and the Topography of Stand-Up 11 2. Nectarines: Carl Reiner and Mel Brooks 28 3. -

Steve Martin

Steve Martin Steve Martin has become one of the world's best-known comedic personalities. Oddly enough, he started out studying philosophy and wanted to become a college professor in the subject. He is a member of Mensa International (an organization for people with very high IQs). His studies, though, turned him in the exact opposite direction. He dropped out of college to pursue a career in comedy writing for numerous television shows before going solo as a stand-up comedian. His experience in philosophy taught him to try ridiculous twists that launched a great career and numerous world renowned catch phrases. Stephen Glenn Martin, born August 14, 1945, is an American comedian, writer, producer, actor, musician and composer. He was born in Waco, Texas and raised in Orange County, California, he worked at Knott’s Berry Farm and Disneyland in concessions. Steve credits this with the beginning of his love for entertainment. He developed his skills in playing the banjo, lassoing, juggling, making balloon animals and improvisational comedy. When he went to college at California State University, long Beach he majored in philosophy. His goal was to become a philosophy professor, but something in his studies changed his mind. “In philosophy, I started studying logic, and they were talking about cause and effect, and you start to realize, ‘Hey, there is no cause and effect! There is no logic! There is no anything!" Then it gets real easy to write this stuff, because all you have to do is twist everything hard - you twist the punch line, you twist the non sequitur so hard away from the things that set I up, that it's easy.. -

25 Cats Name Sam and One Blue Pussy, Ca. 1954 [Written by Charles

25 Cats Name Sam and One Blue Pussy, ca. 1954 [written by Charles Lisanby; printed by Semour Berlin] bound artist’s book with 36 pages and 18 plates offset prints on paper with hand coloring Gift of Richard F. Holmes, Class of 1946 95.18.4 25 Cats Name Sam and One Blue Pussy is one of Warhol’s first promotional books from his years as a commercial artist. The drawings reveal the telltale blotted line technique characteristic of his early graphic work. Warhol used such a line to give his drawings a “printed” feel, and many works were later serially reproduced via offset lithography. In this book, each sketch is accompanied by the name “Sam,” written, not in the artist’s hand, but in the distinctive, whimsical script of Warhol’s mother, Julia. Originally from Slovinia, Warhol’s mother knew little English and when she would painstakingly copy the text Andy asked her to write, she occasionally dropped letters or made misspellings. “Name” in the book’s title is an instance of this kind of accidental elision. Warhol had this book printed and bound and then enlisted friends to help hand color them. Following 25 Cats Name Sam, Warhol created The Gold Book (ca. 1956), a collection of blotted line drawings of friends, flowers, and shoes, on gold paper (inspired by the gold lacquer work he had seen during a trip to Bangkok). Then Warhol composed In the Bottom of My Garden (ca. 1956) replete with slightly suspect cherubs, followed by Wild Raspberries (ca. 1959), a joke cookbook with Suzie Frankfurt’s recipes. -

Origins of the Genre in Search of the Radio Sitcom

1 Origins of the Genre In Search of the Radio Sitcom DAVID MARC The introduction of a mass communication medium normally occurs when an economically viable commercial application is found for a new technol- ogy. A third element necessary to the launch, content (i.e., something to communicate), is often treated as something of an afterthought in this process. As a result, adaptations of popular works and of entire genres from previous media tend to dominate the introductory period, even as they mutate under the developing conditions of the new medium. Such was the case in the rise of the television sitcom from the ashes of network radio. While a dozen or more long-running network radio series served as sources for early television situation comedies, it is in some ways misleading to describe these radio programs (e.g., Father Knows Best, Amos ’n’ Andy, or The Life of Riley) as “radio sitcoms.” According to the Oxford English Dic- tionary, neither the term “situation comedy” nor “sitcom” achieved common usage until the 1950s, the point at which this type of entertainment had become completely absent from American radio. TV Guide appears to be among the first general circulation publica- tions to use the term “situation comedy” in print with the following passage cited by the Oxford English Dictionary from a 1953 article: “Ever since I Love Lucy zoomed to the top rung on the rating ladder, it seems the networks have been filling every available half-hour with another situation comedy” (TV Guide). The abbreviated form, “sitcom,” which probably enjoys greater usage today, has an even shorter history. -

Art Directors Guild to Induct Three Legendary Production Designers Into Its Hall of Fame at 19Th Annual Excellence in Production Design Awards January 31, 2015

ART DIRECTORS GUILD TO INDUCT THREE LEGENDARY PRODUCTION DESIGNERS INTO ITS HALL OF FAME AT 19TH ANNUAL EXCELLENCE IN PRODUCTION DESIGN AWARDS JANUARY 31, 2015 LOS ANGELES, October 15 — Three legendary Production Designers – John Gabriel Beckman, Charles Lisanby and Walter H. Tyler – will be inducted into the Art Directors Guild (ADG) Hall of Fame at the Guild’s 19th Annual Excellence in Production Design Awards ceremony to be held at the Beverly Hilton Hotel on January 31, 2015, as announced today by ADG Council Chairman John Shaffner and Awards Producers Dave Blass and James Pearse Connelly. In making the announcement Shaffner said, “Beckman, Lisanby and Tyler join an honored and distinguished group of ADG Hall of Famers, whose collective work parallels the best of motion picture and television production design. Their enduring legacy and accomplished mastery of our profession are most worthy, influential, inspiring and welcomed additions.” Nominations for the 19th Annual ADG Excellence in Production Design Awards will be announced on January 5, 2015. The ADG will present winners in 11 competitive categories for theatrical films, television productions, commercials and music videos on awards night, January 31, hosted by Comedian Owen Benjamin. JOHN GABRIEL BECKMAN (1898 – 1989) Award winning Production Designer John Gabriel Beckman was an architect prior to becoming an admired American set designer, art director, production designer and muralist. He worked behind-the-scenes for almost a decade before receiving his first screen credit as an art director for Charlie Chaplin’s 1947 black comedy Monsieur Verdoux (which was screened in May as part of ADG’s Film Society Series).