Six Basic Factors in Handwriting Classification Theodora Leh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

19Th Century Writing Activity: Pen &

Lesson Plan: #NoyesArtatHome 19th Century Writing Activity: Pen & Ink Activity based on letters on display in the Noyes Museum’s Estell Empire Exhibition For ages 12 & up Experience with cursive* writing not necessary Assistance from an adult would be helpful. Overview: Round Hand Script: This was the dominant cursive* writing style among 19th century writing “masters,” whose An account book from John Estell’s general store models were engraved on metal. Letters Circa 1836 – 1837 sloped to the right, and thick lines were © Collection of Stockton University produced on the downstrokes using a flexible, straight-edged (not pointed) pen nib (tip). Thin lines were made by using the corner of the nib. Round hand included decorative swirls referred to as “command of hand.” Copperplate: This type of writing was made with a flexible, pointed metal pen. Copperplate script differs from round hand in the gradual swelling of the broad strokes on curved forms and the narrowness of the backstrokes of b, e, and o. Definitions from Britannica.com: https://www.britannica.com/topic/black-letter Project Description: This lesson provides a brief overview of handwriting in the 19th century and a hands-on writing activity. First, paint with a teabag to make “old” looking paper. To write, use a quill** pen with black ink or watered-down paint, or a marker. Try to read and copy the example of 19th century writing. Can you write your own name, or a whole letter to a friend? Supplies: 8.5 x 11” piece of paper A tea bag; preferably a darker tea such as black tea (Lipton, Red Rose) A watercolor brush Your choice of: a quill** pen and black ink, watered-down black paint with a fine-tipped brush, or a black marker (for example: Crayola – “broad line” or Sharpie – “fine point,” the newer, the better) *Cursive writing is a style of writing in which all of the letters in a word are connected. -

Quill Pen and Nut Ink

Children of Early Appalachia Quill Pen and Nut Ink Grades 3 and up Early writing tools were made from materials people could find or easily make themselves. Children used a slate with chalk and stone to write lessons at schools. They also practiced drawing and writing with a stick in dirt. Penny pencils for slates were available at general stores. Paper was purchased at stores too. Before the invention of pencils and pens, children used carved twigs or goose-quill pens made by the teacher. Ink was made at home from various ingredients (berries, nuts, roots, and soot) and brought to school. Good penmanship was highly valued but difficult to attain. Objective: Students will make pen and ink from natural materials and try writing with these old- fashioned tools. Materials: Pen: feathers, sharp scissors or a pen knife (Peacock or pheasant feathers make wonderful pens, but any large feather from a goose or turkey works well too.) Ink: 10 walnut shells, water, vinegar, salt, hammer, old cloth, saucepan, small jar with lid, strainer. (After using the homemade ink, students make like to continue practicing writing with the quill, so you may want to provide a bottle of manufactured ink for further quill writings.) Plan: Pen: Cut off the end of the feather at a slant. Then cut a narrow slit at the point of the pen. Ink: 1. Crush the shells in cloth with a hammer. 2. Put shells in saucepan with 1 cup of water. Bring to a boil, and then simmer for 45 minutes or until dark brown. -

Penmanship Activity Pack

A Day in a One-Room Schoolhouse Marathon County Historical Society Living History Learning Project Penmanship Lesson Activity Packet For Virtual Visits Project Coordinators: Anna Chilsen Straub & Sandy Block Mary Forer: Executive Director (Rev. 6/2020) Note to Participants This packet contains information students can use to prepare for an off-site experience of a one-room school. They may be used by classroom teachers to approximate the experience without traveling to the Little Red Schoolhouse. They are available here for students who might be unable to attend in person for any reason. In addition, these materials may be used by anyone interested in remembering or exploring educational experiences from more than a century ago. The usual lessons at the Little Red Schoolhouse in Marathon Park are taught by retired local school teachers and employees of the Marathon County Historical Society in Wausau, Wisconsin. A full set of lessons has been video-recorded and posted to our YouTube channel, which you can access along with PDFs of accompanying materials through the Little Red Schoolhouse page on our website. These PDFs may be printed for personal or classroom educational purposes only. If you have any questions, please call the Marathon County Historical Society office at 715-842-5750 and leave a message for Anna or Sandy, or email Sandy at [email protected]. On-Site Schoolhouse Daily Schedule 9:00 am Arrival Time. If you attended the Schoolhouse in person, the teacher would ring the bell to signal children to line up in two lines, boys and girls, in front of the door. -

Off-The-Shelf Stylus: Using XR Devices for Handwriting and Sketching on Physically Aligned Virtual Surfaces

TECHNOLOGY AND CODE published: 04 June 2021 doi: 10.3389/frvir.2021.684498 Off-The-Shelf Stylus: Using XR Devices for Handwriting and Sketching on Physically Aligned Virtual Surfaces Florian Kern*, Peter Kullmann, Elisabeth Ganal, Kristof Korwisi, René Stingl, Florian Niebling and Marc Erich Latoschik Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) Group, Informatik, University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany This article introduces the Off-The-Shelf Stylus (OTSS), a framework for 2D interaction (in 3D) as well as for handwriting and sketching with digital pen, ink, and paper on physically aligned virtual surfaces in Virtual, Augmented, and Mixed Reality (VR, AR, MR: XR for short). OTSS supports self-made XR styluses based on consumer-grade six-degrees-of-freedom XR controllers and commercially available styluses. The framework provides separate modules for three basic but vital features: 1) The stylus module provides stylus construction and calibration features. 2) The surface module provides surface calibration and visual feedback features for virtual-physical 2D surface alignment using our so-called 3ViSuAl procedure, and Edited by: surface interaction features. 3) The evaluation suite provides a comprehensive test bed Daniel Zielasko, combining technical measurements for precision, accuracy, and latency with extensive University of Trier, Germany usability evaluations including handwriting and sketching tasks based on established Reviewed by: visuomotor, graphomotor, and handwriting research. The framework’s development is Wolfgang Stuerzlinger, Simon Fraser University, Canada accompanied by an extensive open source reference implementation targeting the Unity Thammathip Piumsomboon, game engine using an Oculus Rift S headset and Oculus Touch controllers. The University of Canterbury, New Zealand development compares three low-cost and low-tech options to equip controllers with a *Correspondence: tip and includes a web browser-based surface providing support for interacting, Florian Kern fl[email protected] handwriting, and sketching. -

Inking Class Links

Inking Scripts, Flourishes and Monograms Workshop - Jeni Buechel Supplemental materials, books and links I will eventually add and expand this list on my website and keep it updated there, (but not yet...) Fabric Inking Supplies- Pens- Rapidograph pens - Koh I Noor My favorite technical pen that you can fill with airbrush paint for textiles available at Amazon (sets are usually a better $ value) Platinum Preppy Fountain Pen remember, this is my favorite $3.30 fountain pen(!) available at Jet Pens Pentel Gel Roller for Fabric Only comes in black and not a very fine point but is washable and in three colors- black, blue, red Sakura Micron Pigma Pens Archival, fine point and can withstand washing but test first for slight feathering of ink on some fabrics. I use these when I don’t want to take the time to do a nice custom job with a rapidograph or fountain pen with airbrush ink Sakura Gel Pens Wide variety of colors (with metallic shades) and washable but lacking a fine point Sharpie Stained Limited to primary colors but washes well. (still haven’t tried it in a fountain pen -but will soon) Fabrico Dual Marker Washable and range of colors but no fine tip Ink and Paint- Airbrush Ink both kinds work in the rapidograph pen or thinned in the fountain pen and both need heat set by iron or in dryer, wide range of colors and custom colors can be mixed Badger Air-Tex Createx Airbrush Colors Dharma Dyeset is a fabric paint (not dye) but very fine pigmented paint that can be used in the rapidograph or fountain pen Iron Gall Ink very old type of ink still available today but is known to deteriorate some natural fiber antique parchments, but it is washable and available in a limited color- black We did discuss Inktense Pencils, watercolor pencils and textile mediums etc.. -

How Handwriting Trains the Brain – Forming Letters Is Key to Learning

How Handwriting Trains the Brain ing by hand engages the brain in learn- hand versus with a keyboard. Forming ing. During one study at Indiana Univer- Even in the digital age, people remain sity published this year, researchers invited enthralled by handwriting for myriad rea- children to man a “spaceship,” actually sons—the intimacy implied by a loved Letters Is Key an MRI machine using a specialized scan one’s script, or what the slant and shape called “functional” MRI that spots neural of letters might reveal about personality. to Learning, activity in the brain. The kids were shown During actress Lindsay Lohan’s proba- letters before and after receiving different tion violation court appearance this sum- Memory, Ideas letter-learning instruction. In children who mer, a swarm of handwriting experts prof- had practiced printing by hand, the neural fered analysis of her blocky courtroom By Gwendoyn Bounds activity was far more enhanced and ”adult- scribbling. “Projecting a false image” and The Wall Street Journal like” than in those who had simply looked “crossing boundaries,” concluded two on Ask preschooler Zane Pike to write at letters. celebrity news and entertainment site hol- his name or the alphabet, then watch this “It seems there is something really im- lywoodlife.com. Beyond identifying per- 4-year-old’s stubborn side kick in. He portant about manually manipulating and sonality traits through handwriting, called spurns practice at school and tosses aside drawing out two-dimensional things we see graphology, some doctors treating neuro- workbooks at home. But Angie Pike, all the time,” says Karin Harman James, as- logical disorders say handwriting can be an Zane’s mom, persists, believing that hand- sistant professor of psychology and neuro- early diagnostic tool. -

Poor Penmanship John M

Research Techniques 15 Techniques to Triumph Over Poor Penmanship John M. Hoenig describes some techniques for reading old handwriting. HOW OFTEN have we trembled at handwriting has changed greatly riage and death certificates. For finding an important document over the years. Check references example, the person filling out the only to have our spirits plummet like Ancestry’s The Source: A marriage certificate for my Peller when we can’t read crucial infor- Guidebook of American Genealogy cousins obviously came from mation? How many of us wish we (Chapter 5) and Unpuzzling Your Europe. could find and afford the services Past (Betterway Books), and search of an expert in penmanship? the online articles at Ancestry’s Techniques for Deciphering a This article describes ways to website www.ancestry.com for tips Handwritten Passage decipher handwriting. To get pre- on reading American handwriting. 1. Study all of the handwriting on pared, it is essential to note what You’ll find, for example, that the the page (or even the surrounding kinds of handwriting you are fac- sequence of letters “ss” appears in pages) to get used to the style. ing. Are you looking at passenger old American handwriting as “fs”. manifests (which were filled out In this article, we illustrate 2. Try to look for several examples where the ship departed, not at techniques for deciphering pen- of every letter of the alphabet Ellis Island where the ship may manship using European hand- (you’ll need to do this separately have arrived)? Are you looking at writing examples but the princi- for upper case and lower case let- American census records? ters). -

Pencil Size and Their Impact on Penmanship Legibility

5 Pencil Size and their Impact on Penmanship Legibility Becky Sinclair Texas A&M University-Commerce Susan Szabo Texas A&M University-Commerce Abstract Legible penmanship is important. However, young students have difficulty producing legible handwriting (Marr, Windsor, & Cermak, 2001). As legible handwriting is a benefit for both the students and the teachers in the classroom setting, this study examined if pencil size had an impact on preschool and kindergarten students’ handwriting. The students used four different pencil sizes over a two-week period. The data showed pencil size did not impact handwriting legibility but there was a pencil size preference difference between preschool and kindergarten students, which may impact the yearly student supply lists. This action research study began after several second-year teachers attended a mandated professional development workshop on the importance of teaching handwriting. During the workshop they learned that writing promotes thinking, builds communication skills, enhances learning and reading, and builds fine motor skills. In addition, they examined the writing Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (TEKS) and found that kindergarten students should be able to form upper and lower-case letters using the basic conventions of print (left to right and top-to- bottom). The teachers were curious to know if pencil size had an impacted preschoolers and kindergarten students’ handwriting legibility. However, they were not interested in writing an article, so they gave us the data to do so. Theoretical Framework There are several theories that can be connected to penmanship: 1) connection theory; and 2) motor learning theory. First, the connection theory looks at the idea that handwriting legibility is related to fluency of writing and reading skills (Rose, 2004). -

Stylus for Fine-Motor Development

Stylus For Fine-Motor Development A Major Qualifying Project Report submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science. Completed by: Shane Whittaker, Nathan Rose, Tom Ward May 2019 Submitted to: Torbjorn Stansen Bergstrom Mechanical Engineering Department Abstract The objective of this project was to improve the writing ability of children, between the ages of 4-6 by encouraging proper grip techniques and practice through the medium of touch screen technology. The rationale of the project was to produce a stylus that enforces the proper grasp development and is intuitive and enjoyable for children to use. The methods we used were, field testing children in a classroom environment, interviewing child care professionals and elementary school teachers, and research of the professional literature on the occupational development of grips, emerging usages of touch screen devices in homes and school for children, and declining writing ability for children occurring in the United States. The results were the creation of two stylus models for two different target groups. One designed for individual case and another designed for general classroom usage. The conclusions reached by the team are: fine motor development has been decreasing in children between the ages of 4-6 in the United States, children are using touch screen technologies at an increasing rate, and the styluses developed by the team will improve children handwriting writing development. 1 Executive Summary Purpose The purpose of our project was to bring a product through the stages of design, prototyping, testing and manufacturing. -

Pencil Size, Pencil Shape, Handwriting, and Handwriting Performance

Review 1 Running head: LITERATURE REVIEW Literature Review Keri Rice Eastern Kentucky University Review 2 Literature Review Handwriting has been an important part of society and education for many centuries and is something that all children entering school must learn. Even before becoming school aged, children spend most of their time coloring, scribbling and then eventually begin writing. Handwriting is now being introduced to children at a young age and is still important in spite of the increasing use of computers. Burns (1962) stated, “The ultimate purpose of handwriting is to express and communicate meaning” (p. 3). Literature to complete this review was obtained from online databases using EBSCOHOST and Education Research Information Center (ERIC). The databases included Academic Search Premier and CINAHL. Google Scholar was also utilized to search for handwriting articles. Keywords for locating literature included pencils, writing instruments, pencil size, pencil shape, handwriting, and handwriting performance. The bound periodicals of the Crabbe Library at Eastern Kentucky University were also utilized. According to Amundson (2005), Occupational therapy practitioners view the occupation of children to be activities of daily living, education, work, play, and social participation. In the area of education, school-aged children’s occupations encompass academic tasks, such as reading, writing, calculation, and problem-solving as well as non-academic or functional ones (p.587). One common academic activity is writing. Writing is a complex process that is used in every day life and one that consumes most of the student’s school day. According to Pape and Ryba (2004), students spend one-third to one-half of the school day engaged in Review 3 pencil and paper activities. -

Reading the (Pdf)

Volume 11, Number 2 $8.50 ARTISTS’ BOOKSbBOOKBINDINGbPAPERCRAFTbCALLIGRAPHY Volume 11, Number 2, February 2014. 3 The Zanerian Experience by Clifford D. Mansley, Sr. 8 The Wearable Book by Thery McKinney 11 Camera Distortion . And How to Avoid It by Colleen Nagel 12 Ritual by Amity Parks 20 Rachel Yallop: Making Letters 27 New Tools & Materials 28 Marbleized Mats from Paper Scraps by Ann Bailey 32 Pencil Books by Peter and Donna Thomas 36 A Letter a Week: Artistic Journeys Through the Alphabet by Fiona Dempster 42 Contributors / credits 47 Subscription information Picnic in Your Dreams. Thery McKinney. “The Wearable Book,” page 8. Bound & Lettered b Winter 2014 1 THE ZANERIAN EXPERIENCE BY CLIFFORD D. MANSLEY, SR. As a boy, as Zaner-Bloser, the company is still in Columbus and produces I had terrible instructional materials on handwriting.) handwriting. The college and the rest of the Zaner-Bloser Company were in the This was not same building, a specially-built brick structure. The downstairs happily consisted of business offices, the studio, and a shipping and received at receiving area. The stairwell to the second floor had large and home, as my beautiful examples of calligraphy on the walls, including lavishly father had, at flourished pieces. (There was also an ancient freight elevator that one time, been took passengers and supplies up the three floors.) The second floor a penmanship had two large classrooms with seating in each for about thirty teacher in the students. (At one time, the school had summer sessions for as many Philadelphia as one hundred penmanship teachers. -

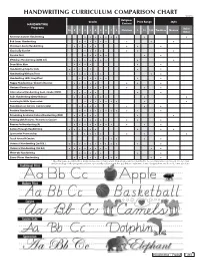

Handwriting Curriculum Comparison Chart

HANDWRITING CURRICULUM COMPARISON CHART ©2018 Religious Grades Price Range Style HANDWRITING Content Programs Italic/ PK K 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Christian $ $$ $$$ Tradition Modern Other American Cursive Handwriting • • • • • • • • • Bob Jones Handwriting • • • • • • • • • Christian Liberty Handwriting • • • • • • • • Classically Cursive • • • • • • • Cursive First • • • • • • • D'Nealian Handwriting (2008 ed.) • • • • • • • • • Draw Write Now • • • • • • Handwriting Help for Kids • • • • • • • Handwriting Without Tears • • • • • • • • • Handwriting Skills Simplified • • • • • • • • Happy Handwriting / Cheerful Cursive • • • • • • • • Horizons Penmanship • • • • • • • • • International Handwriting Cont. Stroke (HMH) • • • • • • • Italic Handwriting (Getty-Dubay) • • • • • • • • • Learning to Write Spencerian • • • • • • • • • New American Cursive (cursive only) • • • • • • • Pentime Handwriting • • • • • • • • • • • Preventing Academic Failure Handwriting (PAF) • • • • • • • Printing with Pictures / Pictures in Cursive • • • • • • • • • • Reason for Handwriting (A) • • • • • • • • • • • Sailing Through Handwriting • • • • • • • • • Spencerian Penmanship • • • • • • • Teach Yourself Cursive • • • • • • Universal Handwriting (2nd Ed.) • • • • • • • • • • • • Universal Handwriting (3rd Ed.) • • • • • • • • • • Write-On Handwriting • • • • • • • Zaner-Bloser Handwriting • • • • • • • • • • • *This chart was assembled by Rainbow Resource Curriculum Consultants and is intended to be a comparative tool based on our own understanding of the programs