Fundamental Truths About Handwriting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

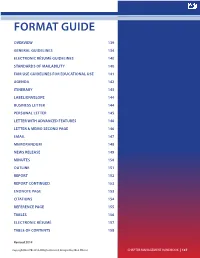

Format Guide

FORMAT GUIDE OVERVIEW 139 GENERAL GUIDELINES 134 ELECTRONIC RÉSUMÉ GUIDELINES 140 STANDARDS OF MAILABILITY 140 FAIR USE GUIDELINES FOR EDUCATIONAL USE 141 AGENDA 142 ITINERARY 143 LABEL/ENVELOPE 144 BUSINESS LETTER 144 PERSONAL LETTER 145 LETTER WITH ADVANCED FEATURES 146 LETTER & MEMO SECOND PAGE 146 EMAIL 147 MEMORANDUM 148 NEWS RELEASE 149 MINUTES 150 OUTLINE 151 REPORT 152 REPORT CONTINUED 153 ENDNOTE PAGE 153 CITATIONS 154 REFERENCE PAGE 155 TABLES 156 ELECTRONIC RÉSUMÉ 157 TABLE OF CONTENTS 158 Revised 2014 Copyright FBLA-PBL 2014. All Rights Reserved. Designed by: FBLA-PBL, Inc CHAPTER MANAGEMENT HANDBOOK | 137 138 | FBLA-PBL.ORG OVERVIEW In today’s business world, communication is consistently expressed through writing. Successful businesses require a consistent message throughout the organization. A foundation of this strategy is the use of a format guide, which enables a corporation to maintain a uniform image through all its communications. Use this guide to prepare for Computer Applications and Word Processing skill events. GENERAL GUIDELINES Font Size: 11 or 12 Font Style: Times New Roman, Arial, Calibri, or Cambria Spacing: 1 space after punctuation ending a sentence (stay consistent within the document) 1 space after a semicolon 1 space after a comma 1 space after a colon (stay consistent within the document) 1 space between state abbreviation and zip code Letters: Block Style with Open Punctuation Top Margin: 2 inches Side and Bottom Margins: 1 inch Bulleted Lists: Single space individual items; double space between items -

19Th Century Writing Activity: Pen &

Lesson Plan: #NoyesArtatHome 19th Century Writing Activity: Pen & Ink Activity based on letters on display in the Noyes Museum’s Estell Empire Exhibition For ages 12 & up Experience with cursive* writing not necessary Assistance from an adult would be helpful. Overview: Round Hand Script: This was the dominant cursive* writing style among 19th century writing “masters,” whose An account book from John Estell’s general store models were engraved on metal. Letters Circa 1836 – 1837 sloped to the right, and thick lines were © Collection of Stockton University produced on the downstrokes using a flexible, straight-edged (not pointed) pen nib (tip). Thin lines were made by using the corner of the nib. Round hand included decorative swirls referred to as “command of hand.” Copperplate: This type of writing was made with a flexible, pointed metal pen. Copperplate script differs from round hand in the gradual swelling of the broad strokes on curved forms and the narrowness of the backstrokes of b, e, and o. Definitions from Britannica.com: https://www.britannica.com/topic/black-letter Project Description: This lesson provides a brief overview of handwriting in the 19th century and a hands-on writing activity. First, paint with a teabag to make “old” looking paper. To write, use a quill** pen with black ink or watered-down paint, or a marker. Try to read and copy the example of 19th century writing. Can you write your own name, or a whole letter to a friend? Supplies: 8.5 x 11” piece of paper A tea bag; preferably a darker tea such as black tea (Lipton, Red Rose) A watercolor brush Your choice of: a quill** pen and black ink, watered-down black paint with a fine-tipped brush, or a black marker (for example: Crayola – “broad line” or Sharpie – “fine point,” the newer, the better) *Cursive writing is a style of writing in which all of the letters in a word are connected. -

IECC Compliance Guide for Homes in New Jersey Code: 2009 International Energy Conservation Code

IECC Compliance Guide for Homes in New Jersey Code: 2009 International Energy Conservation Code Step-by-Step Instructions 1. Using the climate zone map to the right, match the jurisdiction to the appropriate IECC climate zone. Use the simplified table of IECC building envelope requirements (below) to determine the basic thermal envelope requirements associated with the jurisdiction. 2. Use the “Outline of 2009 IECC Requirements” printed on the back of this sheet as a reference or a categorized index to the IECC requirements. Construct the building according to the requirements of the IECC and other applicable code requirements. The 2009 International Energy Conservation Code The 2009 IECC was developed by the International Code Council (ICC) and is currently available to states for adoption. The IECC is the national model standard for energy-efficient residential construction recognized by federal law. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 makes funds available to jurisdictions, like New Jersey, that have committed to adopt and implement the 2009 IECC. Users of this guide are strongly recommended to obtain a copy of the IECC and refer to it for any questions and further details on compliance. IECC CLIMATE ZONE 5 compliance training is also available from many sources. To Bergen Morris Sussex obtain a copy of the 2009 IECC, contact the ICC or visit Hunterdon Passaic Warren www.iccsafe.org. Mercer Somerset Limitations This guide is an energy code compliance aid for New Jersey based upon the simple prescriptive option of the 2009 IECC. It CLIMATE ZONE 4 does not provide a guarantee for meeting the IECC. -

Invisible-Punctuation.Pdf

... ' I •e •e •4 I •e •e •4 •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • ••••• • • •• • • • • • I •e •e •4 In/visible Punctuation • • • • •• • • • •• • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • ' •• • • • • • John Lennard •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • •• • • • • • I •e •e •4 I •e •e •4 I •e •e •4 I •e •e •4 I •e •e •4 I ••• • • 4 I.e• • • 4 I ••• • • 4 I ••• • • 4 I ••• • • 4 I ••• • • 4 • • •' .•. • . • .•. •. • ' .. ' • • •' .•. • . • .•. • . • ' . ' . UNIVERSITY OF THE WEST INDIES- LENNARD, 121-138- VISIBLE LANGUAGE 45.1/ 2 I •e •e' • • • • © VISIBLE LANGUAGE, 2011 -RHODE ISLAND SCHOOL OF DESIGN- PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND 02903 .. ' ABSTRACT The article offers two approaches to the question of 'invisible punctuation,' theoretical and critical. The first is a taxonomy of modes of punctuational invisibility, · identifying denial, repression, habituation, error and absence. Each is briefly discussed and some relations with technologies of reading are considered. The second considers the paragraphing, or lack of it, in Sir Philip Sidney's Apology for Poetry: one of the two early printed editions and at least one of the two MSS are mono paragraphic, a feature always silently eliminated by editors as a supposed carelessness. It is argued that this is improbable -

Chapter Two Literature Review in This Study, the Researcher Shows

11 Chapter Two Literature Review In this study, the researcher shows definition and theory in literature review. The researcher writes some definition of punctuation marks taken from some researchers. Then, the researcher also adds review of related study that contains some research results taken from some researchers. The last is conceptual framework. The researcher takes summary from the theory from some researchers before. English Punctuation According to Jones (1994, p.421) “punctuation, as we consider it, can be defined as the central part of the range of non-lexical orthography”. Allthough arguments could be made for including the sub-lexical marks (e.g. hyphens, apostrolphes ) and structural marlcs (e.g. bullets in itemisations), they are excluded since they tend to be lexicalised or rather difficult to represent, respectively. The other concept comes from Samson (2014, p.23). He said, “punctuation enables us to clarify statements and communicate better with readers.” It is similar with the opinion from Ritter (2001, p. 112) said that “Punctuation exists to clarify meaning in the written word and to facilitate reading. Too much can hamper understanding through an uneven, staccato text, while too little can lead to misreading. Within the framework of a few basic rules (fewer still in fiction), an 12 author's choice of punctuation is an ingredient of style as personal as his or her choice of words.” Writing Writing is an outward expression of what is going on in the writer’s mind (Hussain, Hanif, Asif, and Rehman, 2013). Furthermore, according to Hussain et al (2013), “writing is the visual medium through which graphical and grammatical system of a language is manifested” (p.832). -

Cap Height Body X-Height Crossbar Terminal Counter Bowl Stroke Loop

Cap Height Body X-height -height is the distance between the -Cap height refers to the height of a -In typography, the body height baseline of a line of type and tops capital letter above the baseline for refers to the distance between the of the main body of lower case a particular typeface top of the tallest letterform to the letters (i.e. excluding ascenders or bottom of the lowest one. descenders). Crossbar Terminal Counter -In typography, the terminal is a In typography, the enclosed or par- The (usually) horizontal stroke type of curve. Many sources con- tially enclosed circular or curved across the middle of uppercase A sider a terminal to be just the end negative space (white space) of and H. It CONNECTS the ends and (straight or curved) of any stroke some letters such as d, o, and s is not cross over them. that doesn’t include a serif the counter. Bowl Stroke Loop -In typography, it is the curved part -Stroke of a letter are the lines that of a letter that encloses the circular make up the character. Strokes may A curving or doubling of a line so or curved parts (counter) of some be straight, as k,l,v,w,x,z or curved. as to form a closed or partly open letters such as d, b, o, D, and B is Other letter parts such as bars, curve within itself through which the bowl. arms, stems, and bowls are collec- another line can be passed or into tively referred to as the strokes that which a hook may be hooked make up a letterform Ascender Baseline Descnder In typography, the upward vertical Lowercases that extends or stem on some lowercase letters, such In typography, the baseline descends below the baselines as h and b, that extends above the is the imaginary line upon is the descender x-height is the ascender. -

The Transformation of Calligraphy from Spirituality to Materialism in Contemporary Saudi Arabian Mosques

The Transformation of Calligraphy from Spirituality to Materialism in Contemporary Saudi Arabian Mosques A dissertation submitted to Birmingham City University in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art and Design By: Ahmad Saleh A. Almontasheri Director of the study: Professor Mohsen Aboutorabi 2017 1 Dedication My great mother, your constant wishes and prayers were accepted. Sadly, you will not hear of this success. Happily, you are always in the scene; in the depth of my heart. May Allah have mercy on your soul. Your faithful son: Ahmad 2 Acknowledgments I especially would like to express my appreciation of my supervisors, the director of this study, Professor Mohsen Aboutorabi, and the second supervisor Dr. Mohsen Keiany. As mentors, you have been invaluable to me. I would like to extend my gratitude to you all for encouraging me to conduct this research and give your valuable time, recommendations and support. The advice you have given me, both in my research and personal life, has been priceless. I am also thankful to the external and internal examiners for their acceptance and for their feedback, which made my defence a truly enjoyable moment, and also for their comments and suggestions. Prayers and wishes would go to the soul of my great mother, Fatimah Almontasheri, and my brother, Abdul Rahman, who were the first supporters from the outset of my study. May Allah have mercy on them. I would like to extend my thanks to my teachers Saad Saleh Almontasheri and Sulaiman Yahya Alhifdhi who supported me financially and emotionally during the research. -

OCR a Level Computer Science H446 Specification

Qualification Accredited Oxford Cambridge and RSA A LEVEL Specification COMPUTER SCIENCE H446 ForH418 first assessment in 2017 For first assessment 2022 Version 2.5 (January 2021) ocr.org.uk/alevelcomputerscience Disclaimer Specifications are updated over time. Whilst every effort is made to check all documents, there may be contradictions between published resources and the specification, therefore please use the information on the latest specification at all times. Where changes are made to specifications these will be indicated within the document, there will be a new version number indicated, and a summary of the changes. If you do notice a discrepancy between the specification and a resource please contact us at: [email protected] We will inform centres about changes to specifications. We will also publish changes on our website. The latest version of our specifications will always be those on our website (ocr.org.uk) and these may differ from printed versions. Registered office: The Triangle Building © 2021 OCR. All rights reserved. Shaftesbury Road Cambridge Copyright CB2 8EA OCR retains the copyright on all its publications, including the specifications. However, registered centres for OCR are permitted to copy material from this OCR is an exempt charity. specification booklet for their own internal use. Oxford Cambridge and RSA is a Company Limited by Guarantee. Registered in England. Registered company number 3484466. Contents Introducing… A Level Computer Science (from September 2015) ii Teaching and learning resources iii Professional development iv 1 Why choose an OCR A Level in Computer Science? 1 1a. Why choose an OCR qualification? 1 1b. Why choose an OCR A Level in Computer Science? 2 1c. -

49 Original Article TWO UNPUBLISHED WOODEN LIDS NOS.1410 and 1411 in EL

Egyptian Journal of Archaeological and Restoration Studies "EJARS " An International peer-reviewed journal published bi-annually Volume 6, Issue 1, June - 2016: pp: 49-57 www. ejars.sohag-univ.edu.eg Original article TWO UNPUBLISHED WOODEN LIDS NOS.1410 AND 1411 IN EL- ASHMUNEIN MAGAZINE Safina, A. Egyptology dept., Faculty of Archaeology, Fayoum Univ., Egypt. E-mail: [email protected] Received 29/2/2016 Accepted 14/5/2016 Abstract The main purpose of this article is the publication and study of two wooden lids in El- Ashmunein Magazine. Illustrated drawings are produced for the first time. The complete text of the five columns of hieroglyphs on the lid No.1410 and of the four columns of the lid No. 1411 are the Nut formula, PT 638- 639 (sections a-d), which were incorporated later into the th last part of the 178 chapter of the Book of the Dead. Keywords: Baboon coffin lid, Pyramid Texts, The underground galleries at Tuna el-Gebel. 1. Introduction The two sycamore wooden lids Gebel (c) [2]. Similar burials were found with which we are concerned in this at Saqqara where, after mummification, paper were probably presented to El- most of the upper level baboons were Ashmunein Magazine by S. Gabra (a) . linen-wrapped and each was deposited They were bequeathed to the museum in its own purpose-built rectangular as part of a collection of wooden wooden box without a plaster filling. objects (b) [1] probably all made in the The boxes were placed in niches which same carpenter’s workshop since they were sealed with limestone slabs [3,4] . -

Acquisition of L2 Phonology – Spanish Meets Croatian

ACQUISITION OF L2 PHONOLOGY – SPANISH MEETS CROATIAN Maša Musulin University of Zagreb Article History: Submitted: 10.06.2015 Accepted: 08.08.2015 Abstract: The phoneme is conceived as a mental image that is stored in our mind and then represented by sounds in speech and graphemes in writing for phonologically based alphabets. The acquisition of L2 phonology includes two very important skills – reading and writing. The information stored in the mind of a speaker interferes with new information produced by the L2 (Robinson, Ellis 2008; Nathan, 2008). What is similar or equal in the target language to one's native language is, while unknown, incorporated one way or another into an existing model, based on prototypicality (Pompeian, 2004, Moreno Fernández, 2010). The process of teaching the sounds, letters and alphabet to foreign students is much shorter than for native speakers because to a foreign student must be given a tool for writing as soon as possible as they have to write what they are learning and memorize new language units (Celce-Murcia, Brinton, Goodwin, 1996). This paper discusses one type of difficulties Spanish learners of Croatian as L2 face when they are introduced to phonology through letters which represent Croatian sounds in order to display the influence of their preexisting phonological concepts. The subjects are ten students from Spain and Latin America. Their task was to read a group of words containing sounds that were predictably hard for them, minimal pairs and a short text. Keywords: phoneme, grapheme, letter, phonological awareness, foreign language 1. INTRODUCTION As literacy has a big impact on phonological awareness in languages with phonological writing, the graphemes that represent the phonemes, including letters, make an integral part of their mental image. -

The Selnolig Package: Selective Suppression of Typographic Ligatures*

The selnolig package: Selective suppression of typographic ligatures* Mico Loretan† 2015/10/26 Abstract The selnolig package suppresses typographic ligatures selectively, i.e., based on predefined search patterns. The search patterns focus on ligatures deemed inappropriate because they span morpheme boundaries. For example, the word shelfful, which is mentioned in the TEXbook as a word for which the ff ligature might be inappropriate, is automatically typeset as shelfful rather than as shelfful. For English and German language documents, the selnolig package provides extensive rules for the selective suppression of so-called “common” ligatures. These comprise the ff, fi, fl, ffi, and ffl ligatures as well as the ft and fft ligatures. Other f-ligatures, such as fb, fh, fj and fk, are suppressed globally, while making exceptions for names and words of non-English/German origin, such as Kafka and fjord. For English language documents, the package further provides ligature suppression rules for a number of so-called “discretionary” or “rare” ligatures, such as ct, st, and sp. The selnolig package requires use of the LuaLATEX format provided by a recent TEX distribution, e.g., TEXLive 2013 and MiKTEX 2.9. Contents 1 Introduction ........................................... 1 2 I’m in a hurry! How do I start using this package? . 3 2.1 How do I load the selnolig package? . 3 2.2 Any hints on how to get started with LuaLATEX?...................... 4 2.3 Anything else I need to do or know? . 5 3 The selnolig package’s approach to breaking up ligatures . 6 3.1 Free, derivational, and inflectional morphemes . -

Quill Pen and Nut Ink

Children of Early Appalachia Quill Pen and Nut Ink Grades 3 and up Early writing tools were made from materials people could find or easily make themselves. Children used a slate with chalk and stone to write lessons at schools. They also practiced drawing and writing with a stick in dirt. Penny pencils for slates were available at general stores. Paper was purchased at stores too. Before the invention of pencils and pens, children used carved twigs or goose-quill pens made by the teacher. Ink was made at home from various ingredients (berries, nuts, roots, and soot) and brought to school. Good penmanship was highly valued but difficult to attain. Objective: Students will make pen and ink from natural materials and try writing with these old- fashioned tools. Materials: Pen: feathers, sharp scissors or a pen knife (Peacock or pheasant feathers make wonderful pens, but any large feather from a goose or turkey works well too.) Ink: 10 walnut shells, water, vinegar, salt, hammer, old cloth, saucepan, small jar with lid, strainer. (After using the homemade ink, students make like to continue practicing writing with the quill, so you may want to provide a bottle of manufactured ink for further quill writings.) Plan: Pen: Cut off the end of the feather at a slant. Then cut a narrow slit at the point of the pen. Ink: 1. Crush the shells in cloth with a hammer. 2. Put shells in saucepan with 1 cup of water. Bring to a boil, and then simmer for 45 minutes or until dark brown.