Do Gated Developments in Isle of Dogs Segregate Local Communities?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residential Update

Residential update UK Residential Research | January 2018 South East London has benefitted from a significant facelift in recent years. A number of regeneration projects, including the redevelopment of ex-council estates, has not only transformed the local area, but has attracted in other developers. More affordable pricing compared with many other locations in London has also played its part. The prospects for South East London are bright, with plenty of residential developments raising the bar even further whilst also providing a more diverse choice for residents. Regeneration catalyst Pricing attraction Facelift boosts outlook South East London is a hive of residential Pricing has been critical in the residential The outlook for South East London is development activity. Almost 5,000 revolution in South East London. also bright. new private residential units are under Indeed pricing is so competitive relative While several of the major regeneration construction. There are also over 29,000 to many other parts of the capital, projects are completed or nearly private units in the planning pipeline or especially compared with north of the river, completed there are still others to come. unbuilt in existing developments, making it has meant that the residential product For example, Convoys Wharf has the it one of London’s most active residential developed has appealed to both residents potential to deliver around 3,500 homes development regions. within the area as well as people from and British Land plan to develop a similar Large regeneration projects are playing further afield. number at Canada Water. a key role in the delivery of much needed The competitively-priced Lewisham is But given the facelift that has already housing but are also vital in the uprating a prime example of where people have taken place and the enhanced perception and gentrification of many parts of moved within South East London to a more of South East London as a desirable and South East London. -

Pan Peninsula London, United Kingdom

Reference Project Pan Peninsula London, United Kingdom Frese OPTIMA Project The tallest Residential Tower in the UK. • Max diff. pressure: 400 kPa • Temperature: 0 to 120°C Pan Peninsula, also known as 1 Millharbour, is an exclusive luxury residential development in the • Dimensions: DN15-DN50 Docklands area of London, near South Quay DLR and Canary Wharf Underground stations. Pan Peninsula is one of several new high-rise residential developments that have sprung up due to • Material: DZR brass increased demand for higher living standards in and around Canary Wharf. • Static pressure: PN25 • For cooling and heating The West Tower contains 430 units, while the East Tower houses 356 units. Residents living on pre- mier floors have exclusive access to the Sky Lounge, located on the 31st floor of the East Tower. The Sky Lounge provides a place where residents can relax, hold meetings and conferences, or Frese MODULA host events. Residents also have access to a Business Centre with meeting room, conference room facilities and a library, all with free WiFi access for residents. • Dimensions: MODULA: DN15-DN20 Solution MODULA Pro: DN15-DN25 Frese OPTIMA & Frese MODULA were installed to ensure the hydraulic balance of the piping and • Max differential pressure: the right temperature in the building. Se Control Valve spec • Material: DZR brass • Static pressure: PN 16 • For cooling and heating applications • Allows backward and forward flushing and coil isolation KNOWLEDGE QUALITY INNOVATION MANUFACTURING CUSTOMER EXCELLENCE FOCUS Frese A/S · Sorøvej 8 · DK-4200 Slagelse · Tel: +45 58 56 00 00 · [email protected] · www.frese.eu. -

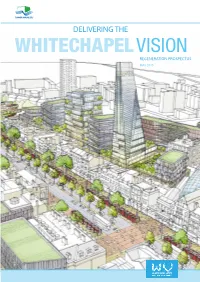

Whitechapel Vision

DELIVERING THE REGENERATION PROSPECTUS MAY 2015 2 delivering the WHitechapel vision n 2014 the Council launched the national award-winning Whitechapel Masterplan, to create a new and ambitious vision for Whitechapel which would Ienable the area, and the borough as a whole, to capitalise on regeneration opportunities over the next 15 years. These include the civic redevelopment of the Old Royal London Hospital, the opening of the new Crossrail station in 2018, delivery of new homes, and the emerging new Life Science campus at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL). These opportunities will build on the already thriving and diverse local community and local commercial centre focused on the market and small businesses, as well as the existing high quality services in the area, including the award winning Idea Store, the Whitechapel Art Gallery, and the East London Mosque. The creation and delivery of the Whitechapel Vision Masterplan has galvanised a huge amount of support and excitement from a diverse range of stakeholders, including local residents and businesses, our strategic partners the Greater London Authority and Transport for London, and local public sector partners in Barts NHS Trust and QMUL as well as the wider private sector. There is already rapid development activity in the Whitechapel area, with a large number of key opportunity sites moving forward and investment in the area ever increasing. The key objectives of the regeneration of the area include: • Delivering over 3,500 new homes by 2025, including substantial numbers of local family and affordable homes; • Generating some 5,000 new jobs; • Transforming Whitechapel Road into a destination shopping area for London • Creating 7 new public squares and open spaces. -

From Sail to Steam: London's Role in a Shipbuilding Revolution Transcript

From Sail to Steam: London's Role in a Shipbuilding Revolution Transcript Date: Monday, 24 October 2016 - 1:00PM Location: Museum of London 24 October 2016 From Sail to Steam: London’s Role in a Shipbuilding Revolution Elliott Wragg Introduction The almost deserted River Thames of today, plied by pleasure boats and river buses is a far cry from its recent past when London was the greatest port in the world. Today only the remaining docks, largely used as mooring for domestic vessels or for dinghy sailing, give any hint as to this illustrious mercantile heritage. This story, however, is fairly well known. What is less well known is London’s role as a shipbuilder While we instinctively think of Portsmouth, Plymouth and the Clyde as the homes of the Royal Navy, London played at least an equal part as any of these right up until the latter half of the 19th century, and for one brief period was undoubtedly the world’s leading shipbuilder with technological capability and capacity beyond all its rivals. Little physical evidence of these vast enterprises is visible behind the river wall but when the tide goes out the Thames foreshore gives us glimpses of just how much nautical activity took place along its banks. From the remains of abandoned small craft at Brentford and Isleworth to unique hulked vessels at Tripcockness, from long abandoned slipways at Millwall and Deptford to ship-breaking assemblages at Charlton, Rotherhithe and Bermondsey, these tantalising remains are all that are left to remind us of London’s central role in Britain’s maritime story. -

Spatial Imaginaries and Tech Cities: Place-Branding East London's Digital Economy

Title Spatial Imaginaries and Tech Cities: Place-branding East London’s digital economy Type Article URL https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/14511/ Dat e 2 0 1 8 Citation Voss, Georgina and Nathan, Max and Vandore, Emma (2018) Spatial Imaginaries and Tech Cities: Place-branding East London’s digital economy. Journal of Economic Geography, 19 (2). pp. 409-432. ISSN 1468-2710 Cr e a to rs Voss, Georgina and Nathan, Max and Vandore, Emma Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected] . License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author FORTHCOMING IN JOURNAL OF ECONOMIC GEOGRAPHY Spatial Imaginaries and Tech Cities: Place-branding East London's digital economy Max Nathan1, Emma Vandore2 and Georgina Voss3 1 University of Birmingham. Corresponding author 2 Kagisha Ltd 3 London College of Communication Corresponding author details: Birmingham Business School, University House, University of Birmingham, BY15 2TY. [email protected] Abstract We explore place branding as an economic development strategy for technology clusters, using London’s ‘Tech City’ initiative as a case study. We site place branding in a larger family of policies that develop spatial imaginaries, and specify affordances and constraints on place brands and brand-led strategies. Using mixed methods over a long timeframe, we analyse Tech City’s emergence and the overlapping, competing narratives that preceded and succeeded it, highlighting day-to-day challenges and more basic tensions. While a strong brand has developed, we cast doubt on claims that policy has had a catalytic effect, at least in the ways originally intended. -

BPL2005AW Baltimore B XXZXX.Qxd:Layout 1 3/11/10 15:04 Page 1

BPL2005AW_Baltimore_B_XXZXX.qxd:Layout 1 3/11/10 15:04 Page 1 in the frame for a spectacular new Docklands residence and a new London icon. The fine art of waterfront living, a masterpiece of light, line and space. BPL2005AW_Baltimore_B_XXZXX.qxd:Layout 1 3/11/10 15:05 Page 2 part of the bigger picture The curtain is being raised on one of the most dynamic residential conceived for a private residence in Europe, and a much sought developments of the 21st century. Docklands’ newest star attraction after facility, its own Montessori Nursery. Be anywhere else you is more than just an apartment complex. This is a beautifully need to be with flawless, express connections to Canary Wharf, conceived future classic, created with exquisite attention to detail the West End, Paris and New York. This is the new heart of the city, and quality. Baltimore is a luxury lifestyle universe: a variety refracted through the lens of cutting-edge contemporary design of picture-perfect contemporary home designs, from the ultimate and impeccable construction, with a dramatic seven-storey pied à terre to a double-height duplex, set around a perfectly architectural aperture on the banks of one of the city’s most landscaped boulevard of clean lines and reflections within historic docks. Exciting, inspiring and serene, a home at Baltimore a sweeping curve of the Thames. Baltimore’s facilities include is the perfect investment and utmost convenience… the most ambitious and radical urban gym and leisure facility ever everything and anything you want it to be. BPL2005AW_Baltimore_B_XXZXX.qxd:Layout 1 3/11/10 15:05 Page 2 aatt thethe heheartart CCanaryanary Wh Wharf:arf: London London’s’s mos mostt iconic iconic financial difinancialstrict and districtone of the and world one’s of mo thest influentiworld’sal bumostsiness influential development business zones. -

THOMSON REUTERS MAP.Ai

PUBLIC TRANSPORT PUBLIC TRANSPORT Watford M Hatfield A1 2 LIMEHOUSE DOCKLAND 1 M25 1 DLR 1 N TRAIN STATION LIGHT RAILWAY M Hendon A1 27 Situated on Commercial Road Canary Wharf Station. Situated High A406 (A13), walk to the Limehouse at the centre of North and South Wycombe Basildon The Thomson Reuters Building M 2 DLR Station and catch a Colonnade. The Station is a two M4 5 South Colonnade 0 A40 A1 3 connecting train to Canary minute walk from our building. A1 3 Slough Canary Wharf Wharf. CITY OF • London C ity LONDON Airport London M4 Tilbury LONDON CITY LONDON UNDERGROUND • A20 5 2 E14 5ep CANARY WHARF • AIRPORT Heathrow A205 M Airport Jubilee Line Extention – links Catch a connecting London Gravesend A3 Croydon Canary Wharf with Waterloo City Airport shuttle bus to SECTION M 2 +44 (0)20 7250 1122 0 Station and London Bridge, Canary Wharf DETAILED M3 BELOW M25 thomsonreuters.com also other tube lines. Wok ing Limehouse MANOR Train Station A Docklands B BURDETT 1 ROAD 1 0 A1 206 2 ROAD Blackwell Tunnel 2 Isle of Dogs 1 Dover A1 02 N C anary Wharf WESTFERRY C IRC US (A1 3) Folkestone COMMERCIAL Royal Docks ROAD C ity 3 C anary A1 Wharf Airport C . London A1 3 One Way COMMERCIAL EAST INDIA ROAD C abot Square DOCK ROAD A1 3 L I M E H O U S E P P C anary Wharf Start here DLR A1 3 A1 3 From the East To Tower Gateway A L L (A1 3) & Central London 6 S A I N T S 0 2 1 P O P L A R Start here W E S T F E R R Y A C . -

Cloud Study CHARLIE GODET THOMAS Bermondsey Square, London, SE1 3UN 3 October 2017 – 30 March 2018 Monday 2 October, Press Launch 5 – 6Pm; Public Launch 6 – 8Pm

Press Release SCULPTURE AT LAUNCHES NEW COMMISSION BY CHARLIE GODET THOMAS Charlie Godet Thomas, Cloud Study sketch, 2017 Cloud Study CHARLIE GODET THOMAS Bermondsey Square, London, SE1 3UN 3 October 2017 – 30 March 2018 Monday 2 October, Press launch 5 – 6pm; Public launch 6 – 8pm VITRINE is delighted to announce that British artist Charlie Godet Thomas will create the second commission for its 2017 – 2018 SCULPTURE AT programme. Entitled Cloud Study, Godet Thomas’ sculpture, which will be unveiled in Bermondsey Square on 2 October 2017, uses the form of a weather vane to represent states of emotional well-being. A speech bubble sits atop a two-metre high vane, which turns in the wind revealing the phrase ‘- yo’ is stuck in thar fo’ever li’l gray cloud.!’ that has been laser cut into the steel shape so as to be visible from both sides. The line comes from the widely syndicated American cartoon ‘Li’l Abner’ created by Al Cap that ran between 1934 – 1977. In the comic strip, one of its characters, Joe Btfsplk, entombs the cloud that bedevils him in a cave, sealing it with a boulder. Similar to the myth of the ostrich burying its head in the sand, the protection this offers is, of course, illusory. A playfully metaphorical work that embraces the personal and political, Cloud Study invites the viewer to meditate on the tragi-comic nature of life, with the movement of the vane mirroring these oscillations as it twists and turns in the wind. Says Charlie Godet Thomas: ‘In Cloud Study, I hope to evade what I see as the traditional hallmarks of public sculpture: for an imposing quality to be substituted by quietness, heroism by the everyday, stillness by function, sternness by humour, and vulnerability in the place of grandstanding.’ Says Director of VITRINE and SCULPTURE AT Alys Williams: ‘SCULPTURE AT was founded with the aim of creating an experimental platform for artists to make work in the public realm; a platform to include artists without previous public sculpture experience. -

Museum of London Docklands: Top 10 Things to See

Museum of London Docklands: Top 10 things to see Until the 20th century shipping was Bronze art from west Africa, such The medieval London Bridge was a Public executions were regarded as This Regency library table was owned vital to the existence of an island nation as these Yoruba sculpture casts, unique and imposing landmark, and this important demonstrations of order and by the MP Thomas Fowel Buxton, who like Britain and all foreign goods arrived demonstrates the high level of craft huge model of it commissioned by the social control, but as an event they were led the campaign in parliament for the by sea. This Roman amphora was accomplishment that existed in the museum gives a dramatic impression of soon over. The corpses of executed abolition of slavery. Buxton was closely an efficient early shipping container, region before the instability and how it would have looked in both the pirates and felons would be tarred to connected to important and radically especially for liquids, and examples like disruption created by the European slave 1400s and the 1600s. You can see how preserve them, then hung in gibbet minded Quakers, and also led campaigns this are found in ship wreck sites all over trade. In the later 19th century examples its function changed from being part of cages like this example at crossroads for prison reform and the restriction of the classical world. It was probably used of bronze castings from west Nigeria and London’s defences, to accommodating or on river banks, as a reminder of the the death penalty. -

Docklands Revitalisation of the Waterfront

Docklands Revitalisation of the Waterfront 1. Introduction 2. The beginning of Docklands 2.1. London’s first port 2.2. The medieval port 2.3. London’s Port trough the ages 3. The end of the harbour 4. The Revitalisation 4.1. Development of a new quarter 4.2. New Infrastructure 5. The result 6. Criticism 7. Sources 1. Introduction Docklands is the semi-official name for an area in east London. It is composed of parts of the boroughs of Southwark, Tower Hamlets, Newham and Greenwich. Docklands is named after docks of the London port which had been in this area for centuries. Between 1960 and 1980, all of London's docks were closed, because of the invention of the container system of cargo transportation. For this system the docks were too small. Consequently London had a big area of derelict land which should be used on new way. The solution was to build up a new quarter with flats, offices and shopping malls. Map with 4 the parts of London Docklands and surrounding boroughs (Source: Wikipedia.org) 2. The beginning of Docklands 2.1. London’s first port Within the Roman Empire which stretched from northern Africa to Scotland and from Spain to Turkey, Londinium (London) became an important centre of communication, administration and redistribution. The most goods and people that came to Britain passed through Londinium. Soon this harbour became the busiest place of whole Londinium. On the river a harbour developed were the ships from the west countries and ships from overseas met. 2.2. The medieval port From 1398 the mayor of London was responsible for conserving the river Thames. -

Leamouth Leam

ROADS CLOSED SATURDAY 05:00 - 21:00 ROADS CLOSED SUNDAY 05:00TO WER 4 2- 12:30 ROADS CLOSED SUNDAY 05:00 - 14:00 3 3 ROUTE MAP ROADS CLOSED SUNDAY 05:00 - 18:00 A1 LEA A1 LEA THE GHERR KI NATCLIFF RATCLIFF RATCLIFF CANNING MOUTH R SATURDAY 4th AUGUST 05:00 – 21:00 MOUTH R SUNDAY 5th AUGUST 05:00 – 14:00 LIMEHOUSE WEST BECKTON AD AD BANK OF WHITECHAPEL BECKTON DOCK RO SUNDAY 5th AUGUST 14:00 – 18:00 TOWN OREGANO DRIVE OREGANO DRIVE CANNING LLOYDS BUILDING SOUTH ST PAUL S ENGL AND Limehouse DLR SEE MAP CUSTOM HOUSE EAST INDIA O EAST INDIA DOCK RO O ROYAL OPER A AD AD CATHED R AL LEAMOUTH DLR PARK OHO LIMEHOUSE LIMEHOUSBecktonE Park Y Y HOUSE Cannon Street Custom House DLR Prince Regent DLR Cyprus DLR Gallions Reach DLR BROMLEY RIGHT A A ROADS CLOSED SUNDAY 05:00 - 18:00 Royal Victoria DLR W W Mansion House COVENT Temple Blackfriars POPLAR DLR DLR Tower Gateway LE A MOUTH OCEA OCEA Monument COMMERC COMMERC V V GARDEN IAL ROAD East India RO UNDABOU T IAL ROAD ExCEL UNIVERSI T Y ROYAL ALBERT SIL SIL ITETIONAL CHASOPMERSETEL Tower Hill Blackwall DLR OF EAST LONDON SEE MAP BELOW RT R AIT HOUSE MILLENIUM ROUNDABOUT DLR Poplar E TOWN GALLE RY BRIDGE A13 VENU A13 VENUE SAFFRON A SAFFRON A SOUTHWARK THE TO WER Westferry DLR DLR BLACKWALL Embankment ROTHERHITH E THE MUSEUM AD AD CLEOPATRA’S BRIDGE OF LONDON EAST INDIA DOCK RO EAST INDIA DOCK RO LONDON WAPPING T UNNEL OF LONDON West India A13 A13 LEAMOUTH NEED LE SHADWELL LONDON CI T Y BRIDGE DOCK L A NDS Quay BILLINGSGATE AIRPOR T A13 K WEST INDIA DOCK RD K WEST INDIA DOCK RD LEA IN M ARKET IN LEAM RATCLIFF L L SE SE MOUT WAY TATE MODERN HMS BELFAST U U SPEN O O AD A N H H A AY A N W E TOWER E E 1 ASPEN 1 H R W E G IM IM 2 2 L L OREGANO DRIVE 0 W 0 OWER LEA CROSSING L CANNING P LOWER LEA CROSSIN BRIDGE 6 O 6 O EAST INDIA DOCK RO POR AD R THE O2 BL ACK WAL L Y T LIMEHOUSE PR ESTO NS A T A A C C HORSE SOUTHWARK W V RO AD T UNNEL O O E V T T . -

The Crystal Palace

The Crystal Palace The Crystal Palace was a cast-iron and plate-glass structure originally The Crystal Palace built in Hyde Park, London, to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. More than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in its 990,000-square-foot (92,000 m2) exhibition space to display examples of technology developed in the Industrial Revolution. Designed by Joseph Paxton, the Great Exhibition building was 1,851 feet (564 m) long, with an interior height of 128 feet (39 m).[1] The invention of the cast plate glass method in 1848 made possible the production of large sheets of cheap but strong glass, and its use in the Crystal Palace created a structure with the greatest area of glass ever seen in a building and astonished visitors with its clear walls and ceilings that did not require interior lights. It has been suggested that the name of the building resulted from a The Crystal Palace at Sydenham (1854) piece penned by the playwright Douglas Jerrold, who in July 1850 General information wrote in the satirical magazine Punch about the forthcoming Great Status Destroyed Exhibition, referring to a "palace of very crystal".[2] Type Exhibition palace After the exhibition, it was decided to relocate the Palace to an area of Architectural style Victorian South London known as Penge Common. It was rebuilt at the top of Town or city London Penge Peak next to Sydenham Hill, an affluent suburb of large villas. It stood there from 1854 until its destruction by fire in 1936. The nearby Country United Kingdom residential area was renamed Crystal Palace after the famous landmark Coordinates 51.4226°N 0.0756°W including the park that surrounds the site, home of the Crystal Palace Destroyed 30 November 1936 National Sports Centre, which had previously been a football stadium Cost £2 million that hosted the FA Cup Final between 1895 and 1914.