Essays-Quantum Theory / Particle Physics/Download/8871

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sterns Lebensdaten Und Chronologie Seines Wirkens

Sterns Lebensdaten und Chronologie seines Wirkens Diese Chronologie von Otto Sterns Wirken basiert auf folgenden Quellen: 1. Otto Sterns selbst verfassten Lebensläufen, 2. Sterns Briefen und Sterns Publikationen, 3. Sterns Reisepässen 4. Sterns Züricher Interview 1961 5. Dokumenten der Hochschularchive (17.2.1888 bis 17.8.1969) 1888 Geb. 17.2.1888 als Otto Stern in Sohrau/Oberschlesien In allen Lebensläufen und Dokumenten findet man immer nur den VornamenOt- to. Im polizeilichen Führungszeugnis ausgestellt am 12.7.1912 vom königlichen Polizeipräsidium Abt. IV in Breslau wird bei Stern ebenfalls nur der Vorname Otto erwähnt. Nur im Emeritierungsdokument des Carnegie Institutes of Tech- nology wird ein zweiter Vorname Otto M. Stern erwähnt. Vater: Mühlenbesitzer Oskar Stern (*1850–1919) und Mutter Eugenie Stern geb. Rosenthal (*1863–1907) Nach Angabe von Diana Templeton-Killan, der Enkeltochter von Berta Kamm und somit Großnichte von Otto Stern (E-Mail vom 3.12.2015 an Horst Schmidt- Böcking) war Ottos Großvater Abraham Stern. Abraham hatte 5 Kinder mit seiner ersten Frau Nanni Freund. Nanni starb kurz nach der Geburt des fünften Kindes. Bald danach heiratete Abraham Berta Ben- der, mit der er 6 weitere Kinder hatte. Ottos Vater Oskar war das dritte Kind von Berta. Abraham und Nannis erstes Kind war Heinrich Stern (1833–1908). Heinrich hatte 4 Kinder. Das erste Kind war Richard Stern (1865–1911), der Toni Asch © Springer-Verlag GmbH Deutschland 2018 325 H. Schmidt-Böcking, A. Templeton, W. Trageser (Hrsg.), Otto Sterns gesammelte Briefe – Band 1, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-55735-8 326 Sterns Lebensdaten und Chronologie seines Wirkens heiratete. -

Executive Committee Meeting 6:00 Pm, November 22, 2008 Marriott Rivercenter Hotel

Executive Committee Meeting 6:00 pm, November 22, 2008 Marriott Rivercenter Hotel Attendees: Steve Pope, Lex Smits, Phil Marcus, Ellen Longmire, Juan Lasheras, Anette Hosoi, Laurette Tuckerman, Jim Brasseur, Paul Steen, Minami Yoda, Martin Maxey, Jean Hertzberg, Monica Malouf, Ken Kiger, Sharath Girimaji, Krishnan Mahesh, Gary Leal, Bill Schultz, Andrea Prosperetti, Julian Domaradzki, Jim Duncan, John Foss, PK Yeung, Ann Karagozian, Lance Collins, Kimberly Hill, Peggy Holland, Jason Bardi (AIP) Note: Attachments related to agenda items follow the order of the agenda and are appended to this document. Key Decisions The ExCom voted to move $100k of operating funds to an endowment for a new award. The ExCom voted that a new name (not Otto Laporte) should be chosen for this award. In the coming year, the Award committee (currently the Fluid Dynamics Prize committee) should establish the award criteria, making sure to distinguish the criteria from those associated with the Batchelor prize. The committee should suggest appropriate wording for the award application and make a recommendation on the naming of the award. The ExCom voted to move Newsletter publication to the first weeks of June and December each year. The ExCom voted to continue the Ad Hoc Committee on Media and Public Relations for two more years (through 2010). The ExCom voted that $15,000 per year in 2009 and 2010 be allocated for Media and Public Relations activities. Most of these funds would be applied toward continuing to use AIP media services in support of news releases and Virtual Pressroom activities related to the annual DFD meeting. Meeting Discussion 1. -

Karl Herzfeld Retained Ties with His Family and with the German Physics Community by Occasional Visits to Germany

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES KARL FERDINAND HERZFELD 1892–1978 A Biographical Memoir by JOSEPH F. MULLIGAN Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoirs, VOLUME 80 PUBLISHED 2001 BY THE NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS WASHINGTON, D.C. Courtesy of AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection KARL FERDINAND HERZFELD February 24, 1892–June 3, 1978 BY JOSEPH F. MULLIGAN ARL F. HERZFELD, BORN in Vienna, Austria, studied at the Kuniversity there and at the universities in Zurich and Göttingen and took courses at the ETH (Technical Insti- tute) in Zurich before receiving his Ph.D. from the University of Vienna in 1914. In 1925, after four years in the Austro- Hungarian Army during World War I and five years as Privatdozent in Munich with Professors Arnold Sommerfeld and Kasimir Fajans, he was named extraordinary professor of theoretical physics at Munich University. A year later he accepted a visiting professorship in the United States at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. This visiting position developed into a regular faculty appointment at Johns Hopkins, which he held until 1936. Herzfeld then moved to Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., where he remained until his death in 1978. As physics chairman at Catholic University until 1961, Herzfeld built a small teaching-oriented department into a strong research department that achieved national renown for its programs in statistical mechanics, ultrasonics, and theoretical research on the structure of molecules, gases, liquids, and solids. During his career Herzfeld published about 140 research papers on physics and chemistry, wrote 3 4 BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS two important books: Kinetische Theorie der Wärme (1925), and (with T. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The new prophet : Harold C. Urey, scientist, atheist, and defender of religion Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3j80v92j Author Shindell, Matthew Benjamin Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The New Prophet: Harold C. Urey, Scientist, Atheist, and Defender of Religion A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History (Science Studies) by Matthew Benjamin Shindell Committee in charge: Professor Naomi Oreskes, Chair Professor Robert Edelman Professor Martha Lampland Professor Charles Thorpe Professor Robert Westman 2011 Copyright Matthew Benjamin Shindell, 2011 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Matthew Benjamin Shindell is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2011 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………………...... iii Table of Contents……………………………………………………………………. iv Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………. -

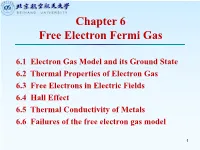

Chapter 6 Free Electron Fermi Gas

理学院 物理系 沈嵘 Chapter 6 Free Electron Fermi Gas 6.1 Electron Gas Model and its Ground State 6.2 Thermal Properties of Electron Gas 6.3 Free Electrons in Electric Fields 6.4 Hall Effect 6.5 Thermal Conductivity of Metals 6.6 Failures of the free electron gas model 1 6.1 Electron Gas Model and its Ground State 6.1 Electron Gas Model and its Ground State I. Basic Assumptions of Electron Gas Model Metal: valence electrons → conduction electrons (moving freely) ü The simplest metals are the alkali metals—lithium, sodium, 2 potassium, cesium, and rubidium. 6.1 Electron Gas Model and its Ground State density of electrons: Zr n = N m A A where Z is # of conduction electrons per atom, A is relative atomic mass, rm is the density of mass in the metal. The spherical volume of each electron is, 1 3 1 V 4 3 æ 3 ö = = p rs rs = ç ÷ n N 3 è 4p nø Free electron gas model: Suppose, except the confining potential near surfaces of metals, conduction electrons are completely free. The conduction electrons thus behave just like gas atoms in an ideal gas --- free electron gas. 3 6.1 Electron Gas Model and its Ground State Basic Properties: ü Ignore interactions of electron-ion type (free electron approx.) ü And electron-eletron type (independent electron approx). Total energy are of kinetic type, ignore potential energy contribution. ü The classical theory had several conspicuous successes 4 6.1 Electron Gas Model and its Ground State Long Mean Free Path: ü From many types of experiments it is clear that a conduction electron in a metal can move freely in a straight path over many atomic distances. -

Free Executive Summary

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/573.html We ship printed books within 1 business day; personal PDFs are available immediately. Biographical Memoirs V.50 Office of the Home Secretary, National Academy of Sciences ISBN: 0-309-59898-2, 416 pages, 6 x 9, (1979) This PDF is available from the National Academies Press at: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/573.html Visit the National Academies Press online, the authoritative source for all books from the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, the Institute of Medicine, and the National Research Council: • Download hundreds of free books in PDF • Read thousands of books online for free • Explore our innovative research tools – try the “Research Dashboard” now! • Sign up to be notified when new books are published • Purchase printed books and selected PDF files Thank you for downloading this PDF. If you have comments, questions or just want more information about the books published by the National Academies Press, you may contact our customer service department toll- free at 888-624-8373, visit us online, or send an email to [email protected]. This book plus thousands more are available at http://www.nap.edu. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF File are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Distribution, posting, or copying is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. Request reprint permission for this book. i e h t be ion. om r ibut f r t cannot r at not Biographical Memoirs o f NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES however, version ng, i t paper book, at ive at rm o riginal horit ic f o e h t he aut t om r as ing-specif t ion ed f peset y http://www.nap.edu/catalog/573.html Biographical MemoirsV.50 publicat her t iles creat is h t L f M of and ot X om yles, r f st version print posed e h heading Copyright © National Academy ofSciences. -

The World Around Is Physics

The world around is physics Life in science is hard What we see is engineering Chemistry is harder There is no money in chemistry Future is uncertain There is no need of chemistry Therefore, it is not my option I don’t have to learn chemistry Chemistry is life Chemistry is chemicals Chemistry is memorizing things Chemistry is smell Chemistry is this and that- not sure Chemistry is fumes Chemistry is boring Chemistry is pollution Chemistry does not excite Chemistry is poison Chemistry is a finished subject Chemistry is dirty Chemistry - stands on the legacy of giants Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier (1743-1794) Marie Skłodowska Curie (1867- 1934) John Dalton (1766- 1844) Sir Humphrey Davy (1778 – 1829) Michael Faraday (1791 – 1867) Chemistry – our legacy Mendeleev's Periodic Table Modern Periodic Table Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev (1834-1907) Joseph John Thomson (1856 –1940) Great experimentalists Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937) Jagadish Chandra Bose (1858 –1937) Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman (1888-1970) Chemistry and chemical bond Gilbert Newton Lewis (1875 –1946) Harold Clayton Urey (1893- 1981) Glenn Theodore Seaborg (1912- 1999) Linus Carl Pauling (1901– 1994) Master craftsmen Robert Burns Woodward (1917 – 1979) Chemistry and the world Fritz Haber (1868 – 1934) Machines in science R. E. Smalley Great teachers Graduate students : Other students : 1. Werner Heisenberg 1. Herbert Kroemer 2. Wolfgang Pauli 2. Linus Pauling 3. Peter Debye 3. Walter Heitler 4. Paul Sophus Epstein 4. Walter Romberg 5. Hans Bethe 6. Ernst Guillemin 7. Karl Bechert 8. Paul Peter Ewald 9. Herbert Fröhlich 10. Erwin Fues 11. Helmut Hönl 12. Ludwig Hopf 13. Walther Kossel 14. -

Wolfgang Pauli 1900 to 1930: His Early Physics in Jungian Perspective

Wolfgang Pauli 1900 to 1930: His Early Physics in Jungian Perspective A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Minnesota by John Richard Gustafson In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Advisor: Roger H. Stuewer Minneapolis, Minnesota July 2004 i © John Richard Gustafson 2004 ii To my father and mother Rudy and Aune Gustafson iii Abstract Wolfgang Pauli's philosophy and physics were intertwined. His philosophy was a variety of Platonism, in which Pauli’s affiliation with Carl Jung formed an integral part, but Pauli’s philosophical explorations in physics appeared before he met Jung. Jung validated Pauli’s psycho-philosophical perspective. Thus, the roots of Pauli’s physics and philosophy are important in the history of modern physics. In his early physics, Pauli attempted to ground his theoretical physics in positivism. He then began instead to trust his intuitive visualizations of entities that formed an underlying reality to the sensible physical world. These visualizations included holistic kernels of mathematical-physical entities that later became for him synonymous with Jung’s mandalas. I have connected Pauli’s visualization patterns in physics during the period 1900 to 1930 to the psychological philosophy of Jung and displayed some examples of Pauli’s creativity in the development of quantum mechanics. By looking at Pauli's early physics and philosophy, we gain insight into Pauli’s contributions to quantum mechanics. His exclusion principle, his influence on Werner Heisenberg in the formulation of matrix mechanics, his emphasis on firm logical and empirical foundations, his creativity in formulating electron spinors, his neutrino hypothesis, and his dialogues with other quantum physicists, all point to Pauli being the dominant genius in the development of quantum theory. -

5 X-Ray Crystallography

Introductory biophysics A. Y. 2016-17 5. X-ray crystallography and its applications to the structural problems of biology Edoardo Milotti Dipartimento di Fisica, Università di Trieste The interatomic distance in a metallic crystal can be roughly estimated as follows. Take, e.g., iron • density: 7.874 g/cm3 • atomic weight: 56 3 • molar volume: VM = 7.1 cm /mole then the interatomic distance is roughly VM d ≈ 3 ≈ 2.2nm N A Edoardo Milotti - Introductory biophysics - A.Y. 2016-17 The atomic lattice can be used a sort of diffraction grating for short-wavelength radiation, about 100 times shorter than visible light which is in the range 400-750 nm. Since hc 2·10−25 J m 1.24 eV µm E = ≈ ≈ γ λ λ λ 1 nm radiation corresponds to about 1 keV photon energy. Edoardo Milotti - Introductory biophysics - A.Y. 2016-17 !"#$%&'$(")* S#%/J&T&U2*#<.%&CKET3&VG$GG./"#%G3&W.%-$/; +(."J&AN&>,%()&CTDB3&S.%)(/3&X.1*&W.%-$/; Y#<.)&V%(Z.&(/&V=;1(21&(/&CTCL&[G#%&=(1&"(12#5.%;&#G&*=.& "(GG%$2*(#/&#G&\8%$;1&<;&2%;1*$)1] 9/(*($));&=.&1*:"(."&H(*=&^_/F*./3&$/"&*=./&H(*=&'$`&V)$/2I&(/& S.%)(/3&H=.%.&=.&=$<()(*$*."&(/&CTBD&H(*=&$&*=.1(1&[a<.% "(.& 9/*.%G.%./Z.%12=.(/:/F./ $/&,)$/,$%$)).)./ V)$**./[?& 7=./&=.&H#%I."&$*&*=.&9/1*(*:*.&#G&7=.#%.*(2$)&V=;1(213&=.$"."& <;&>%/#)"&Q#--.%G.)"3&:/*()&=.&H$1&$,,#(/*."&G:))&,%#G.11#%&$*& *=.&4/(5.%1(*;&#G&0%$/IG:%*&(/&CTCL3&H=./&=.&$)1#&%.2.(5."&=(1& Y#<.)&V%(Z.?& !"#$%"#&'()#**(&8 9/*%#":2*#%;&<(#,=;1(21&8 >?@?&ABCD8CE Arnold Sommerfeld (1868-1951) ... Four of Sommerfeld's doctoral students, Werner Heisenberg, Wolfgang Pauli, Peter Debye, and Hans Bethe went on to win Nobel Prizes, while others, most notably, Walter Heitler, Rudolf Peierls, Karl Bechert, Hermann Brück, Paul Peter Ewald, Eugene Feenberg, Herbert Fröhlich, Erwin Fues, Ernst Guillemin, Helmut Hönl, Ludwig Hopf, Adolf KratZer, Otto Laporte, Wilhelm LenZ, Karl Meissner, Rudolf Seeliger, Ernst C. -

OTTO LAPORTE July 23,1902-March 28,1971

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES O T T O L APORTE 1902—1971 A Biographical Memoir by H. R. CR A N E A N D D. M . D ENNISON Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1979 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. OTTO LAPORTE July 23,1902-March 28,1971 BY H. R. CRANE AND D. M. DENNISON* TTO LAPORTE was a member of the small group of brilliant O young theoretical physicists who received their training during the middle 1920s under the guidance of Arnold Sommer- feld in Munich. Otto Laporte was born in Mainz, Germany. His ancestral lineage came from French Huguenot families who fled from France to Switzerland during the period of intense religious persecution in the late seventeenth century. They were later allowed by Frederick the Great to move to Prussia, where they and their descendants became, for the most part, civil servants in the Prussian State. It appears that Otto was the first member of his family to devote himself to science or any other scholarly career. His father was a career officer in the Imperial German Army, and his specialty was heavy artillery. During the years before World War I, Colonel Laporte was successively stationed in the heavily fortified cities of Mainz, Cologne, and Metz, and it was in these cities that young Otto Laporte received his early schooling. After the war broke out, the family was evacuated from Metz and returned to Mainz, where Otto's mother's family lived. -

Spring 2001 Prizes and Awards

SpringPrizesPrizesPrizes andandand 2001AwardsAwardsAwards APS Announces Spring 2001 Prize and Award Recipients Thirty-seven APS prizes and 1980’s he elaborated with his grenoble 2001 OLIVER E. BUCKLEY PRIZE 2001 DANNIE HEINEMAN PRIZE awards will be presented during spe- group the prototypes of ECR Ion Sources (ECRIS) for highly charge gaseous and cial sessions at three spring meetings Alan Harold Luther Vladimir Igorevich Arnol’d metallic ions, and advocated their utiliza- of the Society: the 2001 March Meet- NORDITA Steklov Institute of Mathematics (Russia) ing, 12-16 March, in Seattle, WA; the tion for new accelerator projects as well 2001 April Meeting, April 28 - May 1, as for the existing cyclotrons, linacs and Citation: “For his fundamental contribu- synchotrons. After retiring from CEA in Victor John Emery in Washington, DC; and the 2001 meet- Brookhaven National Laboratory tions to our understanding of dynamics 1992, he joined the Institut des Sciences and of singularities of maps with profound ing of the APS Division of Atomic, Nucliaires, Grenoble. Molecular and Optical Physics, May Citation: “For their fundamental contribu- consequences for mechanics, astrophysics, 15-19, in London, Ontario, Canada. Ci- Lyneis received his tion to the theory of interacting electrons statistical mechanics, hydrodynamics and optics.” tations and biographical information PhD in physics from in one dimension.” Stanford University for each recipient follow. Additional Alan Harold Luther re- Arnold received his in 1974 and went on biographical information and appro- ceived his PhD (Physics), PhD from the Keldysh to work in the High in 1967 from the Univer- Institute of Applied priate Web links can be found at the Energy Physics Labo- sity of Maryland. -

APS Announces Spring 2002 Prize and Award Recipients

SpringPrizes and 2002Awards APS Announces Spring 2002 Prize and Award Recipients Thirty-seven APS prizes and ception of the Brookhaven Relativistic Mumbai, India. Jain’s most important con- Schwarz received his awards will be presented during spe- Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC). tribution has been his introduction of Ph.D. in 1966 from U.C. cial sessions at three spring meetings electron-flux combinations called “compos- Berkeley. He joined ite fermions”. Jain has extended and Princeton University as a of the Society: the 2001 March Meet- 2002 BIOLOGICAL PHYSICS ing, 12-16 March, in Seattle, WA; the developed the theory of composite fermi- junior faculty member in PRIZE ons into several directions, in particular, 1966. In 1972 he moved to 2001 April Meeting, April 28 - May 1, Carlos Bustamente toward extracting detailed quantitative infor- Caltech, where he has re- in Washington, DC; and the 2001 meet- mation which can be compared with exact mained ever since. Schwarz has worked ing of the APS Division of Atomic, University of California, Berkeley results as well as experiment. on superstring theory for almost his en- Molecular and Optical Physics, May tire professional career. In 1984 Michael Citation: “For his pioneering work in single Read received his Ph.D. 15-19, in London, Ontario, Canada. Ci- Green and he discovered an anomaly can- molecule biophysics and the elucidation of the for work in Condensed tations and biographical information cellation mechanism, which resulted in fundamental physics principles underlying the Matter Theory in 1986 for each recipient follow. Additional string theory becoming one of the hottest mechanical properties and forces involved in from Imperial College, areas in theoretical physics.