© University Press of Florida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Space Impact of the Euro Crisis 50 Years After Mariner 2: Exploration at a Crossroads

0827_SPN_DOM_00_019_00 (READ ONLY) 8/24/2012 11:39 AM Page 19 www.spacenews.com SPACENEWS 19 August27, 2012 TheSpaceImpact of the Euro Crisis < ROBBIN LAIRD and HARALD MALMGREN > he European sovereign debt crisis Europe will now be challenged in the ing to hide the reality of European bank of the savings of millions of European is not simply abump in historical form of rollbacks of the many inter- weaknesses. The main reason is that eu- citizens. Tprogress; it is the end of aperiod twined strands of integration, fraying rozone economies are far more bank- European leaders are also attempt- of historyand acritical point in Euro- what has been an intricate but incom- dependent than economies like those in ing to initiate amore comprehensive fis- pean and global transition in the 21st plete tapestry. It is questionable whether the United States or United Kingdom, cal union, with new decision-making century. Europe will be able to prevent stalling of where substantial nonbank financing al- mechanisms that transfer sovereignty in The confluence of several trend lines the integration process in the face of ternatives exist for the corporate sector. parallel with the new banking union. We — the unification of Germany,the end widening gaps among the interests of In the eurozone, banks are the fi- do not believe that any of the eurozone of the Soviet Union, the collapse of the each nation and even within each nation. nancial markets; in the U.S., banks are governments are ready for such apoliti- Berlin Wall, the expansion of NATO, Since the birth of the euro, the but one segment of amultifaceted fi- cal transition in which citizens in each the expansion of the European Union French and Germans were in the lead in nancial market. -

University of Iowa Instruments in Space

University of Iowa Instruments in Space A-D13-089-5 Wind Van Allen Probes Cluster Mercury Earth Venus Mars Express HaloSat MMS Geotail Mars Voyager 2 Neptune Uranus Juno Pluto Jupiter Saturn Voyager 1 Spaceflight instruments designed and built at the University of Iowa in the Department of Physics & Astronomy (1958-2019) Explorer 1 1958 Feb. 1 OGO 4 1967 July 28 Juno * 2011 Aug. 5 Launch Date Launch Date Launch Date Spacecraft Spacecraft Spacecraft Explorer 3 (U1T9)58 Mar. 26 Injun 5 1(U9T68) Aug. 8 (UT) ExpEloxrpelro r1e r 4 1915985 8F eJbu.l y1 26 OEGxOpl o4rer 41 (IMP-5) 19697 Juunlye 2 281 Juno * 2011 Aug. 5 Explorer 2 (launch failure) 1958 Mar. 5 OGO 5 1968 Mar. 4 Van Allen Probe A * 2012 Aug. 30 ExpPloiorenre 3er 1 1915985 8M Oarc. t2. 611 InEjuxnp lo5rer 45 (SSS) 197618 NAouvg.. 186 Van Allen Probe B * 2012 Aug. 30 ExpPloiorenre 4er 2 1915985 8Ju Nlyo 2v.6 8 EUxpKlo 4r e(rA 4ri1el -(4IM) P-5) 197619 DJuenc.e 1 211 Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission / 1 * 2015 Mar. 12 ExpPloiorenre 5e r 3 (launch failure) 1915985 8A uDge.c 2. 46 EPxpiolonreeerr 4130 (IMP- 6) 19721 Maarr.. 313 HMEaRgCnIe CtousbpeShaetr i(cF oMxu-1ltDis scaatelell itMe)i ssion / 2 * 2021081 J5a nM. a1r2. 12 PionPeioenr e1er 4 1915985 9O cMt.a 1r.1 3 EExpxlpolorerer r4 457 ( S(IMSSP)-7) 19721 SNeopvt.. 1263 HMaalogSnaett oCsupbhee Sriact eMlluitlet i*scale Mission / 3 * 2021081 M5a My a2r1. 12 Pioneer 2 1958 Nov. 8 UK 4 (Ariel-4) 1971 Dec. 11 Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission / 4 * 2015 Mar. -

Information Summaries

TIROS 8 12/21/63 Delta-22 TIROS-H (A-53) 17B S National Aeronautics and TIROS 9 1/22/65 Delta-28 TIROS-I (A-54) 17A S Space Administration TIROS Operational 2TIROS 10 7/1/65 Delta-32 OT-1 17B S John F. Kennedy Space Center 2ESSA 1 2/3/66 Delta-36 OT-3 (TOS) 17A S Information Summaries 2 2 ESSA 2 2/28/66 Delta-37 OT-2 (TOS) 17B S 2ESSA 3 10/2/66 2Delta-41 TOS-A 1SLC-2E S PMS 031 (KSC) OSO (Orbiting Solar Observatories) Lunar and Planetary 2ESSA 4 1/26/67 2Delta-45 TOS-B 1SLC-2E S June 1999 OSO 1 3/7/62 Delta-8 OSO-A (S-16) 17A S 2ESSA 5 4/20/67 2Delta-48 TOS-C 1SLC-2E S OSO 2 2/3/65 Delta-29 OSO-B2 (S-17) 17B S Mission Launch Launch Payload Launch 2ESSA 6 11/10/67 2Delta-54 TOS-D 1SLC-2E S OSO 8/25/65 Delta-33 OSO-C 17B U Name Date Vehicle Code Pad Results 2ESSA 7 8/16/68 2Delta-58 TOS-E 1SLC-2E S OSO 3 3/8/67 Delta-46 OSO-E1 17A S 2ESSA 8 12/15/68 2Delta-62 TOS-F 1SLC-2E S OSO 4 10/18/67 Delta-53 OSO-D 17B S PIONEER (Lunar) 2ESSA 9 2/26/69 2Delta-67 TOS-G 17B S OSO 5 1/22/69 Delta-64 OSO-F 17B S Pioneer 1 10/11/58 Thor-Able-1 –– 17A U Major NASA 2 1 OSO 6/PAC 8/9/69 Delta-72 OSO-G/PAC 17A S Pioneer 2 11/8/58 Thor-Able-2 –– 17A U IMPROVED TIROS OPERATIONAL 2 1 OSO 7/TETR 3 9/29/71 Delta-85 OSO-H/TETR-D 17A S Pioneer 3 12/6/58 Juno II AM-11 –– 5 U 3ITOS 1/OSCAR 5 1/23/70 2Delta-76 1TIROS-M/OSCAR 1SLC-2W S 2 OSO 8 6/21/75 Delta-112 OSO-1 17B S Pioneer 4 3/3/59 Juno II AM-14 –– 5 S 3NOAA 1 12/11/70 2Delta-81 ITOS-A 1SLC-2W S Launches Pioneer 11/26/59 Atlas-Able-1 –– 14 U 3ITOS 10/21/71 2Delta-86 ITOS-B 1SLC-2E U OGO (Orbiting Geophysical -

AIAA Fellows

AIAA Fellows The first 23 Fellows of the Institute of the Aeronautical Sciences (I) were elected on 31 January 1934. They were: Joseph S. Ames, Karl Arnstein, Lyman J. Briggs, Charles H. Chatfield, Walter S. Diehl, Donald W. Douglas, Hugh L. Dryden, C.L. Egtvedt, Alexander Klemin, Isaac Laddon, George Lewis, Glenn L. Martin, Lessiter C. Milburn, Max Munk, John K. Northrop, Arthur Nutt, Sylvanus Albert Reed, Holden C. Richardson, Igor I. Sikorsky, Charles F. Taylor, Theodore von Kármán, Fred Weick, Albert Zahm. Dr. von Kármán also had the distinction of being the first Fellow of the American Rocket Society (A) when it instituted the grade of Fellow member in 1949. The following year the ARS elected as Fellows: C.M. Bolster, Louis Dunn, G. Edward Pendray, Maurice J. Zucrow, and Fritz Zwicky. Fellows are persons of distinction in aeronautics or astronautics who have made notable and valuable contributions to the arts, sciences, or technology thereof. A special Fellow Grade Committee reviews Associate Fellow nominees from the membership and makes recommendations to the Board of Directors, which makes the final selections. One Fellow for every 1000 voting members is elected each year. There have been 1980 distinguished persons elected since the inception of this Honor. AIAA Fellows include: A Arnold D. Aldrich 1990 A.L. Antonio 1959 (A) James A. Abrahamson 1997 E.C. “Pete” Aldridge, Jr. 1991 Winfield H. Arata, Jr. 1991 H. Norman Abramson 1970 Buzz Aldrin 1968 Johann Arbocz 2002 Frederick Abbink 2007 Kyle T. Alfriend 1988 Mark Ardema 2006 Ira H. Abbott 1947 (I) Douglas Allen 2010 Brian Argrow 2016 Malcolm J. -

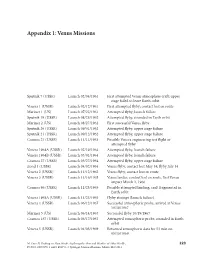

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

JHU/APL Colloquia

JHU Applied Physics Laboratory Colloquia November 15, 2019 www.jhuapl.edu/colloquium/archive [email protected] 2019 – 2020 Stephen Moore (Author and Journalist) UNCOMMON VALOR: Recon Company Medal of Honor Heroes of FOB-2. November 8, 2019. Lawrence Goldstone (Author) Going Deep: John Philip Holland and the Invention of the Attack Submarine. November 1, 2019. David Blodgett (JHU/APL) Optical Imaging of the Brain: Is There Really Anything to See? October 25, 2019. Larrie D. Ferreiro (George Mason Univ.) Brothers at Arms: American Independence and the Men of France and Spain Who Saved It. October 18, 2019. Dr. Etta Pisano, M.D., FACR (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center) The Tomosynthesis Mammographic Imaging Screening Trial (TMIST) – A Bridge to Personalized Breast Cancer Screening. October 16, 2019. Héctor L. Díaz (Hispanics In History Cultural Organization) The Hispanic Assistance to the American Revolution. October 11, 2019. Andrés Muñoz-Jaramillo (Southwest Research Institute) How the Hemispheric Polar Field Reversal Sets the Timing and Shape of the Solar Cycle. October 9, 2019. Dave "Bio" Baranek (Author, "TOPGUN Days") Topgun and Tomcats: High Explosives, Type-A Personalities, and Prandtl–Meyer Expansion Fans. October 4, 2019. 2018 – 2019 Mojie Crigler (END Fund) Under the Big Tree: Extraordinary Stories From the Movement to End Neglected Tropical Diseases. September 27, 2019. CAPT Mercedes Benitez-McCrary, Dr.HSc, MA CCC-SLP (Chief Professional Officer - Chief Therapist Officer, United States Public Health Service) “Puentes Y Verjas” – Hispanic Health. September 20, 2019. Eric Haseltine (Analyst and Consultant) The Spy in Moscow Station: A Counterspy's Hunt for a Deadly Cold War Threat. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 154 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 6, 2008 No. 19 House of Representatives The House met at 2 p.m. and was THE JOURNAL world peace can occur by sitting called to order by the Speaker pro tem- The SPEAKER pro tempore. The around smoking dope and banging on pore (Mr. BAIRD). Chair has examined the Journal of the the tambourine. Berkeley should lose all Federal f last day’s proceedings and announces to the House his approval thereof. funding for their smug denouncement DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- of the Marine Corps. Patriotic Ameri- PRO TEMPORE nal stands approved. cans should not subsidize cities that tell the Marines to ‘‘get out of town.’’ The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- f And as for the Marines, we’ll take fore the House the following commu- PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE nication from the Speaker: them all in Texas. We’ll have a parade, The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the fly the flag, and sing the Marine Hymn. WASHINGTON, DC, gentleman from Florida (Mr. MILLER) February 6, 2008. So Semper Fi. come forward and lead the House in the I hereby appoint the Honorable BRIAN And that’s just the way it is. BAIRD to act as Speaker pro tempore on this Pledge of Allegiance. day. Mr. MILLER of Florida led the f NANCY PELOSI, Pledge of Allegiance as follows: Speaker of the House of Representatives. -

2005 Annual Report American Physical Society

1 2005 Annual Report American Physical Society APS 20052 APS OFFICERS 2006 APS OFFICERS PRESIDENT: PRESIDENT: Marvin L. Cohen John J. Hopfield University of California, Berkeley Princeton University PRESIDENT ELECT: PRESIDENT ELECT: John N. Bahcall Leo P. Kadanoff Institue for Advanced Study, Princeton University of Chicago VICE PRESIDENT: VICE PRESIDENT: John J. Hopfield Arthur Bienenstock Princeton University Stanford University PAST PRESIDENT: PAST PRESIDENT: Helen R. Quinn Marvin L. Cohen Stanford University, (SLAC) University of California, Berkeley EXECUTIVE OFFICER: EXECUTIVE OFFICER: Judy R. Franz Judy R. Franz University of Alabama, Huntsville University of Alabama, Huntsville TREASURER: TREASURER: Thomas McIlrath Thomas McIlrath University of Maryland (Emeritus) University of Maryland (Emeritus) EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Martin Blume Martin Blume Brookhaven National Laboratory (Emeritus) Brookhaven National Laboratory (Emeritus) PHOTO CREDITS: Cover (l-r): 1Diffraction patterns of a GaN quantum dot particle—UCLA; Spring-8/Riken, Japan; Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lab, SLAC & UC Davis, Phys. Rev. Lett. 95 085503 (2005) 2TESLA 9-cell 1.3 GHz SRF cavities from ACCEL Corp. in Germany for ILC. (Courtesy Fermilab Visual Media Service 3G0 detector studying strange quarks in the proton—Jefferson Lab 4Sections of a resistive magnet (Florida-Bitter magnet) from NHMFL at Talahassee LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT APS IN 2005 3 2005 was a very special year for the physics community and the American Physical Society. Declared the World Year of Physics by the United Nations, the year provided a unique opportunity for the international physics community to reach out to the general public while celebrating the centennial of Einstein’s “miraculous year.” The year started with an international Launching Conference in Paris, France that brought together more than 500 students from around the world to interact with leading physicists. -

What Famous Computer Person(S)

I Won a famous prize also won by Jane Goodall, Noam Chomsky, and John Cage? (Kyoto) I Won a famous prize also won by the chemist Linus Pauling, physicist John Bardeen, economist Herbert Simon, and the astronomer James van Allen? (NMS) I Proudly puts an INTERCAL program they wrote on their home page? (Abandon sanity) I Dedicated their first book to a computer “in remembrance of many pleasant evenings”? I Instead of celebrating their 65th birthday, celebrated their millionth ((1000000)2 = 64 birthday)? I Along with Richard Stallman and Linus Torvalds is regarded as one of the three pioneers of open-source software? I Introduced big-O notation to the computer science community? What famous computer person(s) I Had their first publication in Mad magazine? I Won a famous prize also won by the chemist Linus Pauling, physicist John Bardeen, economist Herbert Simon, and the astronomer James van Allen? (NMS) I Proudly puts an INTERCAL program they wrote on their home page? (Abandon sanity) I Dedicated their first book to a computer “in remembrance of many pleasant evenings”? I Instead of celebrating their 65th birthday, celebrated their millionth ((1000000)2 = 64 birthday)? I Along with Richard Stallman and Linus Torvalds is regarded as one of the three pioneers of open-source software? I Introduced big-O notation to the computer science community? What famous computer person(s) I Had their first publication in Mad magazine? I Won a famous prize also won by Jane Goodall, Noam Chomsky, and John Cage? (Kyoto) I Proudly puts an INTERCAL program they -

Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars

NASA Facts National Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91109 Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars Between 1962 and late 1973, NASA’s Jet carry a host of scientific instruments. Some of the Propulsion Laboratory designed and built 10 space- instruments, such as cameras, would need to be point- craft named Mariner to explore the inner solar system ed at the target body it was studying. Other instru- -- visiting the planets Venus, Mars and Mercury for ments were non-directional and studied phenomena the first time, and returning to Venus and Mars for such as magnetic fields and charged particles. JPL additional close observations. The final mission in the engineers proposed to make the Mariners “three-axis- series, Mariner 10, flew past Venus before going on to stabilized,” meaning that unlike other space probes encounter Mercury, after which it returned to Mercury they would not spin. for a total of three flybys. The next-to-last, Mariner Each of the Mariner projects was designed to have 9, became the first ever to orbit another planet when two spacecraft launched on separate rockets, in case it rached Mars for about a year of mapping and mea- of difficulties with the nearly untried launch vehicles. surement. Mariner 1, Mariner 3, and Mariner 8 were in fact lost The Mariners were all relatively small robotic during launch, but their backups were successful. No explorers, each launched on an Atlas rocket with Mariners were lost in later flight to their destination either an Agena or Centaur upper-stage booster, and planets or before completing their scientific missions. -

N€WS 'RELEASE NATIONAL AERONAUTICS and SPACE Admln ISTRATION 400 MARYLAND AVENUE, SW, WASHINGTON 25, D.C

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=19630002483 2020-03-11T16:50:02+00:00Z b " N€WS 'RELEASE NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMlN ISTRATION 400 MARYLAND AVENUE, SW, WASHINGTON 25, D.C. TELEPHONES WORTH 2-4155-WORTH. 3-1110 RELEASE NO. 62-182 MARINER SPACECRAFT Mariner 2, the second of a series of spacecraft designed for planetary exploration,- will be launched within a few days (no earlier than August 17) from the Atlantic Missile Range, Cape Canaveral, Florida, by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Mariner 1, launched at 4:21 a.m. (EST) on July 22, 1962 from AMR, was destroyed by the Range Safety Officer after about 290 seconds of flight because of a deviation from the planned flight path. Measures have been taken to correct the difficulties experienced in the Mariner 1 launch. These measures include a more rigorous checkout of the Atlas rate beacon and revision of the data editing equation. The data editing equation Is designed as a guard against acceptance of faulty databy the ground guidance equipment. The Mariner 2 spacecraft and its mission are identical to the first Mariner. Mariner 2 will carry six experiments. Two of these instruments, infrared and microwave radiometers, will make measurements at close range as Mariner 2 flys by Venus and communicate this in€ormation over an interplanetary distance of 36 million miles, Four other experiments on the spacecraft -- a magnetometer, ion chamber and particle flux detector, cosmic dust detector and solar plasma spectrometer -- will gather Information on interplantetary phenomena during the trip to Venus and in the vicinity of the planet. -

So, Has Voyager 1 Left the Solar System? Scientists Face Off Cosmic-Ray Fluctuations Could Mean the Craft Has Exited the Sun's Magnetic Field

NATURE | NEWS So, has Voyager 1 left the Solar System? Scientists face off Cosmic-ray fluctuations could mean the craft has exited the Sun's magnetic field. Ron Cowen 21 March 2013 A space physicist this week suggests that NASA’s venerable Voyager 1 spacecraft has become the first vehicle to venture beyond the heliosphere — the magnetic bubble created by the Sun — but other mission scientists disagree. William Webber of New Mexico State University in Las Cruces bases the claim on signals recorded last August by the Voyager 1 cosmic-ray subsystem — a device that he helped to build — along with his late colleague and study co-author Francis McDonald. JPL-Caltech/NASA Voyager 1 recorded a sudden drop in cosmic rays The instrument recorded a dramatic drop in the intensity of the cosmic rays trapped last August, a possible sign that it had left the in the Sun’s magnetic field and a concomitant rise in that of rays generated by more Sun's sphere of influence. distant reaches of the Galaxy. That pattern indicates that Voyager 1 has travelled beyond the Sun’s magnetic influence and is no longer being shielded from galactic cosmic rays, the researchers report in a study published online this week in Geophysical Research Letters1. But if one is to believe a press release issued by NASA on 20 March (the same day the report was published), the two researchers jumped the gun. Other Voyager scientists who analysed the same data last autumn reiterate what they said then: the cosmic-ray data indicate that Voyager 1 is in a transition zone within the outer part of the heliosphere, but until a dramatic change in magnetic-field intensity and direction is detected, the craft remains firmly within the Sun’s magnetic sphere of influence.