Old Glory: a Practical Investigation Into Pattern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heraldry Examples Booklet.Cdr

Book Heraldry Examples By Khevron No color on color or metal on metal. Try to keep it simple. Make it easy to paint, applique’ or embroider. Blazon in layers from the deepest layer Per pale vert and sable all semy of caltrops e a talbot passant argent. c up to the surface: i v Field (color or division & colors), e Primary charge (charge or ordinary), Basic Book Heraldry d Secondary charges close to the primary, by Khevron a Tertiary charges on the primary or secondary, Device: An heraldic representation of youself. g Peripheral secondary charges (Chief,Canton,Border), Arms: A device of someone with an Award of Arms. n i Tertiary charges on the peropheral. Badge: An heraldic representation of what you own. z a Name field tinctures chief/dexter first. l Only the first word, the metal Or, B and proper nouns are capitalized. 12 2 Tinctures, Furs & Heraldic 11 Field Treatments Cross Examples By Khevron By Khevron Crosses have unique characteristics and specific names. Tinctures: Metals and Colors Chief Rule #1: No color upon another color, or metal on metal! Canton r r e e t t s i x e n - Fess - i D Or Argent Sable Azure Vert Gules Purpure S Furs Base Cross Latin Cross Cross Crosslet Maltese Potent Latin Cross Floury Counter-Vair Vair Vair in PaleVair-en-pointe Vair Ancient Ermine Celtic Cross Cross Gurgity Crosslet Fitchy Cross Moline Cross of Bottony Jerusalem A saltire vair in saltire Vair Ermines or Counter- Counter Potent Potent-en-pointe ermine Cross Quarterly in Saltire Ankh Patonce Voided Cross Barby Cross of Cerdana Erminois Field -

THE LION FLAG Norway's First National Flag Jan Henrik Munksgaard

THE LION FLAG Norway’s First National Flag Jan Henrik Munksgaard On 27 February 1814, the Norwegian Regent Christian Frederik made a proclamation concerning the Norwegian flag, stating: The Norwegian flag shall henceforth be red, with a white cross dividing the flag into quarters. The national coat of arms, the Norwegian lion with the yellow halberd, shall be placed in the upper hoist corner. All naval and merchant vessels shall fly this flag. This was Norway’s first national flag. What was the background for this proclamation? Why should Norway have a new flag in 1814, and what are the reasons for the design and colours of this flag? The Dannebrog Was the Flag of Denmark-Norway For several hundred years, Denmark-Norway had been in a legislative union. Denmark was the leading party in this union, and Copenhagen was the administrative centre of the double monarchy. The Dannebrog had been the common flag of the whole realm since the beginning of the 16th century. The red flag with a white cross was known all over Europe, and in every shipping town the citizens were familiar with this symbol of Denmark-Norway. Two variants of The Dannebrog existed: a swallow-tailed flag, which was the king’s flag or state flag flown on government vessels and buildings, and a rectangular flag for private use on ordinary merchant ships or on private flagpoles. In addition, a number of special flags based on the Dannebrog existed. The flag was as frequently used and just as popular in Norway as in Denmark. The Napoleonic Wars Result in Political Changes in Scandinavia At the beginning of 1813, few Norwegians could imagine dissolution of the union with Denmark. -

Mainufer the Fairground in Offenbach

Das MDasess eMegeländessegel äindn eO ffein nbOffeachnbach Einladung EinladungInvit Invitationation ndin4 . ndina eaath eather erday dsays Einladung Invitation TheThe faThfairgroundirgroe fairgrunds inounds Offenbachin Offe in nbaOffechnbach MainuferMainuferMainufer VeranstalterVeranstalterVeranstalter OrganO rganizerizerOrganizer COUNCC OIL U N CFORCO IL UNC FORLEATHER IL LEATH FOR EXPORTS LEA ERTH EXPOER (EXPORTSSponsored R TS (Sponsored (Sponsored by Ministr by Mby inistry Ministrof of y of Vom Flughafen: From the International Airport Das MessegeländeDas Messegelände in Offen- in Offen- The fairgTheroun fairgds irnoun Ofdsfen ibnac Offh enbachVom Flughafen:Vom Flughafen: From theFrom International the International Airport AirportCo mmeC omrce m erceCommerc& Industry & Industry,e &, Industry,G ovGovt.t. ofof India),GIndiovt.a) Chennai,of, ChennaIndia), Indiai, Chennai,India India The fairground in Offenbach bach liegtbach i mliegt Zentrum im ZentrumEuropas ,Eur opasnext, to nextFrank tfourt Frank aref urtlocate ared lo cateAutobahnd Autobahn A3A3 RichtungRichtung A3 Würzburg/Richtung Würzburg/ Würzburg/ Frankfurt:Frankfurt: Frankfurt: www.leatherindia.org.w w w .leatherindia.org. www.leatherindia.org. _Lederwaren Veranstalter Organizer Deutschlands Deutschlands und der undRhein der- Rhein-nextin the to Frankfurtcenterin the o centerisf locatedEurope, of Euofro Geper-, of OffenbacherGer- Offenbacher Kreuz, dann dannKreuz, die die A661 dann A661 die HighwayHighway A661 Highway A3A3 direction A3 Würzburg/direction Würzburg/ Würzburg/ -

Vexillum, June 2018, No. 2

Research and news of the North American Vexillological Association June 2018 No. Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine de vexillologie Juin 2018 2 INSIDE Page Editor’s Note 2 President’s Column 3 NAVA Membership Anniversaries 3 The Flag of Unity in Diversity 4 Incorporating NAVA News and Flag Research Quarterly Book Review: "A Flag Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of National Symbols" 7 New Flags: 4 Reno, Nevada 8 The International Vegan Flag 9 Regional Group Report: The Flag of Unity Chesapeake Bay Flag Association 10 Vexi-News Celebrates First Anniversary 10 in Diversity Judge Carlos Moore, Mississippi Flag Activist 11 Stamp Celebrates 200th Anniversary of the Flag Act of 1818 12 Captain William Driver Award Guidelines 12 The Water The Water Protectors: Native American Nationalism, Environmentalism, and the Flags of the Dakota Access Pipeline Protectors Protests of 2016–2017 13 NAVA Grants 21 Evolutionary Vexillography in the Twenty-First Century 21 13 Help Support NAVA's Upcoming Vatican Flags Book 23 NAVA Annual Meeting Notice 24 Top: The Flag of Unity in Diversity Right: Demonstrators at the NoDAPL protests in January 2017. Source: https:// www.indianz.com/News/2017/01/27/delay-in- nodapl-response-points-to-more.asp 2 | June 2018 • Vexillum No. 2 June / Juin 2018 Number 2 / Numéro 2 Editor's Note | Note de la rédaction Dear Reader: We hope you enjoyed the premiere issue of Vexillum. In addition to offering my thanks Research and news of the North American to the contributors and our fine layout designer Jonathan Lehmann, I owe a special note Vexillological Association / Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine of gratitude to NAVA members Peter Ansoff, Stan Contrades, Xing Fei, Ted Kaye, Pete de vexillologie. -

Cruciform Heraldry (Solution)

Cruciform Heraldry (Solution) This puzzle is presented as a cross-shaped arrangement of coats of arms. Other than the blank one showing a question mark, the coats of arms are those of 25 of the 26 cantons of Switzerland, which is also hinted at by the title, the initials of which are the same as the abbreviation for Switzerland (CH, Confoederatio Helvetica), and the name of the font used in the title (Helvetica). Also, the dimensions of the cross are exactly the dimensions of the cross in the Swiss coat of arms and flag. The missing 26th coat of arms is that of Vaud, which says “LIBERTÉ ET PATRIE” on it. The puzzle is a cryptogram. Each of the boxed rows contains the name of a municipality in Switzerland (or a district in the case of Appenzell Innerrhoden, which does not have municipalities and whose districts are equivalent to municipalities in other cantons), where diacritics and hyphens have been preserved, which makes one of the names (Châtel-sur-Montsalvens) an easy way to break into the cryptogram. The decrypted grid is shown below, where the missing letters are marked in red. O R P U N D R I E H E N D O Z W I L E B I K O N R A M S E N B U O C H S Y V O R N E C H A T E L S U R M O N T S A L V E N S A C Q U A R O S S A N E N Z L I N G E N T R O G E N O B E R E G G N E U H E I M L I C H T E N S T E I G E R S T F E L D T U R B E N T H A L T S C H E P P A C H E N G E L B E R G R E B E U V E L I E R M E Y R I N A B T W I L P E S E U X P I G N I U I L L G A U N E N D A Z G L A R U S . -

Selected Bibliography of Work on Canadian Ethnic Minority Writing

UNIVERSITY PRESS <http://www.thepress.purdue.edu> CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb> Purdue University Press ©Purdue University The Library Series of the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access quarterly in the humanities and the social sciences CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture publishes scholarship in the humanities and social sciences following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the CLCWeb Library Series are 1) articles, 2) books, 3) bibliographies, 4) resources, and 5) documents. Contact: <[email protected]> Selected Bibliography of Work on Canadian Ethnic Minority Writing <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweblibrary/canadianethnicbibliography> Steven Tötösy de Zepetnek, Asma Sayed, and Domenic A. Beneventi 1) literary histories and bibliographies of canadian ethnic minority writing 2) work on canadian ethnic minority writing This selected bibliography is compiled according to the following criteria: 1) Only English- and French-language works are included; however, it should be noted that there exists a substantial corpus of studies in a number Canada's ethnic minority languages; 2) Critical works about the literatures of Canada's First Nations are not included following the frequently expressed opinion that Canadian First Nations literatures should not be categorized within Canadian "Ethnic" writing but as a separate corpus; 3) Literary criticism as well as theoretical texts are included; 4) Critical texts on works of authors writing in English and French but usually viewed or which could be considered as "Ethnic" authors (i.e., immigré[e]/exile individuals whose works contain Canadian "Ethnic" perspectives) are included; 5) Some works dealing with US or Anglophone-American Ethnic Minority Writing with Canadian perspectives are included; 6) M.A. -

Guide to South Dakota Norwegian-American Collections

GUIDE TO COLLECTIONS RELATING TO SOUTH DAKOTA NORWEGIAN-AMERICANS Compiled by Harry F. Thompson, Ph.D. Director of Research Collections and Publications The Center for Western Studies With the assistance of Arthur R. Huseboe, Ph.D. and Paul B. Olson Additional assistance by Carol Riswold, D. Joy Harris, and Laura Plowman Originally published in 1991 by The Center for Western Studies, Augustana College, Sioux Falls, SD 57197 and updated in 2007. Original publication was made possible by a grant from the South Dakota Committee on the Humanities and by a gift from Harold L. Torness of Sisseton, South Dakota. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Albright College 2 Augustana College, The Center for Western Studies 3 Augustana College, Mikkelsen Library 4 Augustana College (IL), Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center 5 Black Hills State University 6 Brookings Public Library 7 Canton Public Library 8 Centerville Public Library 9 Codington County Historical Society 10 Cornell University Libraries 11 Dakota State University 12 Dakota Wesleyan University 13 Dewey County Library 14 Elk Point Community Library 15 Grant County Public Library 16 Phoebe Apperson Hearst Library 17 J. Roland Hove 18 Luther College 19 Minnehaha County Historical Society 20 Minnehaha County Rural Public Library 21 Minnesota Historical Society, Research Center 2 22 Mitchell Area Genealogical Society 23 Mobridge Public Library 24 National Archives--Central Plains Region 25 North Dakota State University, North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies 26 Norwegian American Historical Association 27 James B. Olson 28 Rapid City Public Library 29 Rapid City Sons of Norway Borgund Lodge I-532 30 Regional Center for Mission--Region III, ELCA 31 St. -

The History of Florida's State Flag the History of Florida's State Flag Robert M

Nova Law Review Volume 18, Issue 2 1994 Article 11 The History of Florida’s State Flag Robert M. Jarvis∗ ∗ Copyright c 1994 by the authors. Nova Law Review is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nlr Jarvis: The History of Florida's State Flag The History of Florida's State Flag Robert M. Jarvis* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........ .................. 1037 II. EUROPEAN DISCOVERY AND CONQUEST ........... 1038 III. AMERICAN ACQUISITION AND STATEHOOD ......... 1045 IV. THE CIVIL WAR .......................... 1051 V. RECONSTRUCTION AND THE END OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY ..................... 1056 VI. THE TWENTIETH CENTURY ................... 1059 VII. CONCLUSION ............................ 1063 I. INTRODUCTION The Florida Constitution requires the state to have an official flag, and places responsibility for its design on the State Legislature.' Prior to 1900, a number of different flags served as the state's banner. Since 1900, however, the flag has consisted of a white field,2 a red saltire,3 and the * Professor of Law, Nova University. B.A., Northwestern University; J.D., University of Pennsylvania; LL.M., New York University. 1. "The design of the great seal and flag of the state shall be prescribed by law." FLA. CONST. art. If, § 4. Although the constitution mentions only a seal and a flag, the Florida Legislature has designated many other state symbols, including: a state flower (the orange blossom - adopted in 1909); bird (mockingbird - 1927); song ("Old Folks Home" - 1935); tree (sabal palm - 1.953); beverage (orange juice - 1967); shell (horse conch - 1969); gem (moonstone - 1970); marine mammal (manatee - 1975); saltwater mammal (dolphin - 1975); freshwater fish (largemouth bass - 1975); saltwater fish (Atlantic sailfish - 1975); stone (agatized coral - 1979); reptile (alligator - 1987); animal (panther - 1982); soil (Mayakka Fine Sand - 1989); and wildflower (coreopsis - 1991). -

The First, Albeit Unofficial, United States National Flag Appeared on 1

Brief History of the Design of the United States Flag The first, albeit unofficial, United States national flag appeared on 1 January 1776 when the new Continental Army became official and General George Washington hoisted the ‘Continental Colors’.1 This flag featured the Union Jack in the canton, to symbolize loyalty to Britain, and thirteen alternating red and white stripes, to symbolize the colonies and their unity.2 Congress took no action in regards to a new flag when they proclaimed the Declaration of Independence.3 Finally, on 14 June 1777, Congress declared that the official United States national flag will have thirteen stripes alternating red and white, and the Union, or canton, will contain thirteen white stars on a blue field.4 Star arrangements within the canton varied, either in rows or in a circle.5 The first official national flag remained until 1795. In 1791 and 1792 Vermont and Kentucky, respectively, joined the union rendering the flag inaccurate. A motion passed by the Senate in 1793 called for two new stars and two new stripes. The new 15-star, 15-stripe flag remained official for the next 23 years.6 When new states entered the union in the decades after 1795, unofficial variations to the national flag appeared. These variations featured additional stars and stripes for each new state. No official government action occurred until Representative Peter Wendover of New York in 1816 suggested Congress set up a flag study committee. On 2 January 1817 Wendover’s committee recommended that the national flag should include thirteen stripes, to represent the original thirteen colonies, and a star for each state in the union with additional stars added when new states are admitted. -

The Canadian Handbook and Tourist's Guide

3 LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAICN IN MEMORY OF STEWART S. HOWE JOURNALISM CLASS OF 1928 STEWART S. HOWE FOUNDATION 917.1 Smlc 1867 cop. H. T.H>ii Old Trapper, v. Photo, : THE CANADIAN HANDBOOK AND Tourists Guide GIVING A DESCRIPTION OF CANADIAN LAKE AND RIVER SCENERY AND PLACES OF HISTORICAL INTEREST WITH THE BEST SPOTS FOR Fishing and Shooting. MONTREAL Published by M. Longmoore & Co., Printing House, 6y Great St. James Street, - 1867. Entered according to the Act of the Provincial Parliament, in the year one thousand eight hundred and sixty-six, by John Taylor, in the Office of the Kegistrar of the Province of Canada. 1 /?./ • . / % . THE CANADIAN HANDBOOK AND TOURIST'S GUIDE. INTRODUCTION. The Nooks and Corners of Canada, and. more especially of the Lower Province, in addition to the interest they awaken as important sources of Commercial and Agricultural wealth, are invested with no ordinary attraction for the Naturalist, the Antiquary, the Historian, and the Tourist in quest of pleasure or of health. We have often wondered why more of the venturesome spirits amongst our transatlantic friends do not tear themselves away, even for a few months, from London fogs, to visit our distant but more favoured clime. How is it that so few, comparatively speaking, come to enjoy the bracing air and bright summer skies of Canada ? With what zest could the enterprising or eccentric among them undertake a ramble, with rod and gun in hand, from Niagara to Labrador, over the Laurentian Chain of Moun- tains, choosing as rallying points, whereat to compare notes, the summit of Cape Eternity in the Saguenay district, and 6 Introduction. -

Flags of the World

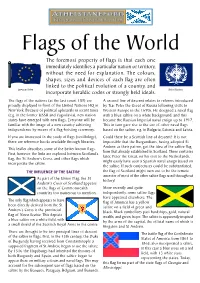

ATHELSTANEFORD A SOME WELL KNOWN FLAGS Birthplace of Scotland’s Flag The name Japan means “The Land Canada, prior to 1965 used the of the Rising Sun” and this is British Red Ensign with the represented in the flag. The redness Canadian arms, though this was of the disc denotes passion and unpopular with the French sincerity and the whiteness Canadians. The country’s new flag represents honesty and purity. breaks all previous links. The maple leaf is the Another of the most famous flags Flags of the World traditional emblem of Canada, the white represents in the world is the flag of France, The foremost property of flags is that each one the vast snowy areas in the north, and the two red stripes which dates back to the represent the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. immediately identifies a particular nation or territory, revolution of 1789. The tricolour, The flag of the United States of America, the ‘Stars and comprising three vertical stripes, without the need for explanation. The colours, Stripes’, is one of the most recognisable flags is said to represent liberty, shapes, sizes and devices of each flag are often in the world. It was first adopted in 1777 equality and fraternity - the basis of the republican ideal. linked to the political evolution of a country, and during the War of Independence. The flag of Germany, as with many European Union United Nations The stars on the blue canton incorporate heraldic codes or strongly held ideals. European flags, is based on three represent the 50 states, and the horizontal stripes. -

Beginner Blazon

Blazon 101 Arwyn of Leicester White Wyvern Herald Submissions Avacal What we will discuss • Definition – Emblazon vs Blazon • Using Emblazon and Blazons in SCA – Submissions – Conflict Check – Display What we will discuss • How to Build a Blazon – Elements of a blazon – Basic Syntax Rules – How to put it together • Resources (on-line, books) Using Emblazon and Blazons in SCA • Submissions – Emblazon – picture of device/badge • This is what is registered – Proposed Blazon vs. Registered Blazon • Local heralds should attempt at a blazon on the submission (Proposed Blazon) • Laurel gives final blazon (registered) Using Emblazon and Blazons in SCA • Conflict Checks – Blazon is what is listed in the armorial – Allows a visual picture to be developed from the description • Display – Scribes can use this to add colour to scrolls – Providing personal banners How to Build a Blazon • Elements of a Blazon – Tinctures • Colours: – azure (blue) – gules (red) – purpure (purple) – sable (black) – vert (green) • Metals: – Or (gold) – Argent (white/silver) How to Build a Blazon • Elements of a Blazon – Tinctures • Furs – Ermine (white with black spots) – Ermines (also called counter ermine –black with white spots) – Erminois (gold with black spots) – Pean (black with gold spots) – Vair (interlocking "bells" alternately white and blue) – Potent (interlocking "T's" alternately white and blue) How to Build a Blazon • Elements of a Blazon – Ordinaries • An ordinary is a charge that consists of one or more strips of a contrasting tincture which cover large areas of the shield. • Examples: – Base – Bordure – Canton – Chief – Pile – Bend How to Build a Blazon • Elements of a Blazon – Directions • Remember that the directions are like you wearing the shield – then the Norman French makes sense • to base (= toward the bottom point of the shield) • to chief (= toward the top edge of the shield) • to dexter (= toward the viewer's left, the shield bearers right) • to sinister (= toward the viewer's right, the shield bears left) How to Build a Blazon • Basic Syntax Rules 1.