Wexman Source: Cinema Journal, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

Cinephilia Or the Uses of Disenchantment 2005

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Thomas Elsaesser Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment 2005 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/11988 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Elsaesser, Thomas: Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment. In: Marijke de Valck, Malte Hagener (Hg.): Cinephilia. Movies, Love and Memory. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press 2005, S. 27– 43. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/11988. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell 3.0 Lizenz zur Verfügung Attribution - Non Commercial 3.0 License. For more information gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie hier: see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment Thomas Elsaesser The Meaning and Memory of a Word It is hard to ignore that the word “cinephile” is a French coinage. Used as a noun in English, it designates someone who as easily emanates cachet as pre- tension, of the sort often associated with style items or fashion habits imported from France. As an adjective, however, “cinéphile” describes a state of mind and an emotion that, one the whole, has been seductive to a happy few while proving beneficial to film culture in general. The term “cinephilia,” finally, re- verberates with nostalgia and dedication, with longings and discrimination, and it evokes, at least to my generation, more than a passion for going to the movies, and only a little less than an entire attitude toward life. -

Empireheads to the Florida Estate of Burt Reynolds To

presents WORDS PORTRAITS Nick de Semlyen Steve Schofi eld EMPIRE HEADS TO THE FLORIDA ESTATE OF BURT REYNOLDS TO SPEND AN ALL-ACCESS WEEKEND WITH THE BANDIT HIMSELF, ONCE THE BIGGEST MOVIE STAR ON THE PLANET TYPE Jordan Metcalf 120 JANUARY 2016 JANUARY 2016 121 Most character-building of all, he shared a New York apartment with Rip Torn. “He was wild,” Reynolds says of the notoriously volatile Men In Black star. “One time they asked me to go duck- hunting in the Roosevelt Game Reserve for (TV show) The American Sportsman, and I took Rip with me. While we were walking around, some geese fl ew above us, squawking. Rip goes, ‘You know what “IF I’D SAID YES TO STAR they’re saying? They’re saying, “That’s the crazy Rip Torn down there.”’ He took his gun, said, ‘I’ll teach that sonuvabitch WARS, IT WOULD HAVE to talk like that,’ and shot one. I said, ‘Rip, you really are crazy.’ But I couldn’t help but love him. Still do.” Reynolds built a reputation as HIS REFRESHMENTS ARE LAID OUT. MEANT NO SMOKEY a fearless man of action, stoked by his A cluster of grapes, a glass of ice water eagerness to do his own stunts. “The and a bowl of Veggie Straws potato fi rst one involved me going through chips (‘Zesty Ranch’ fl avour), arranged AND THE BANDIT…” a plate-glass window on a show called lovingly on a side-table. Frontiers Of Faith,” he says. “I got 125 The students are assembled. This bucks — a nice chunk of change in 1957.” Friday night, 18 of them have come. -

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

Blurred Lines Between Role and Reality: a Phenomenological Study of Acting

Antioch University AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive Student & Alumni Scholarship, including Dissertations & Theses Dissertations & Theses 2019 Blurred Lines Between Role and Reality: A Phenomenological Study of Acting Gregory Hyppolyte Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://aura.antioch.edu/etds Part of the Psychology Commons BLURRED LINES BETWEEN ROLE AND REALITY: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL STUDY OF ACTING A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Antioch University Santa Barbara In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY In CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY by GREGORY HIPPOLYTE BROWN August 2019 This dissertation, by Gregory Hippolyte Brown, has been approved by the committee members signed below who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of Antioch University Santa Barbara in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Committee: _________________________ Brett Kia-Keating, Ed.D. Chairperson __________________________ Sharleen O‘ Brien, Ph.D. Second Faculty __________________________ Thalia R. Goldstein, Ph.D. External Expert ii Copyright © 2019 Gregory Hippolyte Brown iii Abstract When an actor plays a character in a film, they try to connect with the emotions and behavioral patterns of the scripted character. There is an absence of literature regarding how a role influences an actor’s life before, during, and after film production. This study examined how acting roles might influence an actor during times on set shooting a movie or television series as well as their personal life after the filming is finished. Additionally the study considered the psychological impact of embodying a role, and whether or not an actor ever has the feeling that the performed character has independent agency over the actor. -

JEAN-LUC GODARD: SON+IMAGE Fact Sheet

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release August 1992 FACT SHEET EXHIBITION JEAN-LUC GODARD: SON+IMAGE DATES October 30 - November 30, 1992 ORGANIZATION Laurence Kardish, curator, Department of Film, with the collaboration of Mary Lea Bandy, director, Department of Film, and Barbara London, assistant curator, video, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art; and Colin Myles MacCabe, professor of English, University of Pittsburgh, and head of research and information, British Film Institute. CONTENT Jean-Luc Godard, one of modern cinema's most influential artists, is equally important in the development of video. JEAN-LUC GODARD: SON+IMAGE traces the relationship between Godard's films and videos since 1974, from the films Ici et ailleurs (1974) and Numero Deux (1975) to episodes from his video series Histoire(s) du Cinema (1989) and the film Nouvelle Vague (1990). Godard's work is as visually and verbally dense with meaning during this period as it was in his revolutionary films of the 1960s. Using deconstruction and reassemblage in works such as Puissance de la Parole (video, 1988) and Allemagne annee 90 neuf zero (film, 1991), Godard invests the sound/moving image with a fresh aesthetic that is at once mysterious and resonant. Film highlights of the series include Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1979), First Name: Carmen (1983), Hail Mary (1985), Soigne ta droite (1987), and King Lear (1987), among others. Also in the exhibition are Scenario du film Passion (1982), the video essay about the making of the film Passion (1982), which is also included, and the videos he created in collaboration with Anne-Marie Mieville, Soft and Hard (1986) and the series made for television, Six fois deux/Sur et sous la communication (1976). -

Course Outline

Degree Applicable Glendale Community College April, 2003 COURSE OUTLINE Theatre Arts 163 Acting Styles Workshop in Contemporary Theatre Production I. Catalog Statement Theatre Arts 163 is a workshop in acting styles designed to support contemporary theatre production. The students enrolled in this course will be formed into a company to present contemporary plays as a part of the season in the Theatre Arts Department at Glendale Community College. Each student will be assigned projects in accordance with his or her interests and talents. The projects will involve some phase of theatrical production as it relates to performance skills in the style of Contemporary World Theatre. Included will be current or recent successful stage play scripts from Broadway, Off-Broadway, West-end London, and other world theatre centers and date back to the style changes in realism in the mid-to-late 1950’s. The rehearsal laboratory consists of 10-15 hours per week. Units -- 1.0 – 3.0 Lecture Hours -- 1.0 Total Laboratory Hours -- 3.0 – 9.0 (Faculty Laboratory Hours -- 3.0 – 9.0 + Student Laboratory Hours -- 0.0 = 3.0 – 9.0 Total Laboratory Hours) Prerequisite Skills: None Note: This course may be taken 4 times; a maximum of 12 units may be earned. II. Course Entry Expectations Skills Expectations: Reading 5; Writing 5; Listening-Speaking 5; Math 1. III. Course Exit Standards Upon successful completion of the required course work, the student will be able to: 1. recognize the professional responsibilities of a producing group associated with the audition, preparation, and performance of a theatre production before a paying, public audience; 2. -

Anne Gordon Center for Active Adults Movie Schedule February 2020 Wednesdays 2:00 PM—4:00 PM FREE Please See the Back for Attendance Rules and Information

Anne Gordon Center for Active Adults Movie Schedule February 2020 Wednesdays 2:00 PM—4:00 PM FREE Please see the back for attendance rules and information. Feb 5 Once Upon a Time in Hollywood Com, Drama Rated: R Runtime: 2:41 Starring: Leonardo DiCaprio, Brad Pitt, Burt Reynolds, Margot Robbie, In 1960s Los Angeles, silver screen actor Rick Dalton and his stunt double turned best friend, Cliff Booth, struggle to keep pace with the swiftly evolving entertainment industry. They both work to continue their notoriety while facing the demise of Hollywood's Golden Age. Rated R for Bloody Images, Drug Use, Language, Sexual Situations, and Violence. Feb 12 Judy Drama, Musical Rated: PG-13 Runtime: 1:58 Starring: Renée Zellweger, Finn Wittrock, Rufus Sewell, Jessie Buckley Set in late 1968 and early 1969, Judy Garland stars in a five-week engagement of Talk of the Town in swinging London. Behind the scenes, she battles her own management and prepares to fight her ex-husband in court for custody of their children. Despite this period of her life being tumultuous, Garland is able to find love once again. Rated PG-13 by the Motion Picture Association of America for Language, Substance Abuse, Thematic Elements. Feb 19 The Farewell Com, Drama Rated: PG Runtime: 1:40 Starring: Awkwafina, Zhao Shuzhen, X Mayo, Tzi Ma, Shuzhen Zhou In this funny, heartfelt story, Billi's family returns to China under the guise of a fake wedding to stealthily say goodbye to their beloved matriarch, who is the only person that doesn't know she only has a few weeks to live. -

SLP Movie Watchlist Week 1

THE SLP MOVIE WATCHLIST™ THE SLP MOVIE WATCHLIST Every Wednesday Your weekly source of movie recommendations to satisfy your cinematic cravings. Table of Contents SLP Movie Watchlist Themes Week 1……………………………...Random Week 2……………………………..Oscar Winners Week 3……………………………..Crime Drama Week 4……………………………..1980s Comedies Week 5……………………………..Johnny Depp Week 6……………………………..Sci-fi Action Week 7……………………………..Documentaries Week 8……………………………..Films over 3 hours Week 9……………………………..Horror Week 10……………………………Romantic Dramas Week 11…………………………….Fantasy Week 12……………………………Inspiring Sports Films Week 13……………………………Movie Musicals Week 14……………………………Westerns Week 15…………………………….Anime Week 16…………………………….Quentin Tarantino Week 17…………………………….Good Bad Movies Week 18…………………………….Drew Barrymore Week 19…………………………….Martin Scorcese Week 20…………………………….Actors in Multiple Roles Mental, written and directed by P.J. Hogan, is a fun film about an eccentric woman who randomly takes on the role as the nanny of five children who have a “crazy” mother. Through her shenanigans she is able to teach them about the madness of life and the importance of family. Toni Collette and Anthony LaPaglia sink themselves into their roles so brilliantly that you lose yourself in their insanity. Oh, and it’s an Aussie film, which adds yet another level of fun! Mental combines the certifiably loony characters of Best In Show with the heartfelt songs of The Sound of Music, literally. Recommended For: People who can appreciate off-the-wall, zany stories! Silver Linings Playbook is a peculiar story about two people who have experienced loss and want to believe in a better tomorrow. Hope gives them comfort. Jennifer Lawrence and Bradley Cooper spend the majority of the film challenging one another, both as characters and actors. -

A Look Into the South According to Quentin Tarantino Justin Tyler Necaise University of Mississippi

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2018 The ineC matic South: A Look into the South According to Quentin Tarantino Justin Tyler Necaise University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Necaise, Justin Tyler, "The ineC matic South: A Look into the South According to Quentin Tarantino" (2018). Honors Theses. 493. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/493 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CINEMATIC SOUTH: A LOOK INTO THE SOUTH ACCORDING TO QUENTIN TARANTINO by Justin Tyler Necaise A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2018 Approved by __________________________ Advisor: Dr. Andy Harper ___________________________ Reader: Dr. Kathryn McKee ____________________________ Reader: Dr. Debra Young © 2018 Justin Tyler Necaise ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii To Laney The most pure-hearted person I have ever met. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my family for being the most supportive group of people I could have ever asked for. Thank you to my father, Heath, who instilled my love for cinema and popular culture and for shaping the man I am today. Thank you to my mother, Angie, who taught me compassion and a knack for looking past the surface to see the truth that I will carry with me through life. -

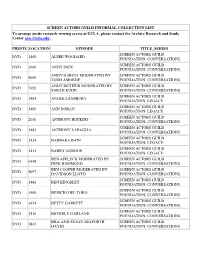

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST to Arrange Onsite Research Viewing Access at UCLA, Please Contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected]

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST To arrange onsite research viewing access at UCLA, please contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected] . PREFIX LOCATION EPISODE TITLE_SERIES SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1460 ALFRE WOODARD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1669 ANDY DICK FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY GARCIA MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8699 TODD AMORDE FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY RICHTER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7020 SARAH KUHN FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1484 ANGLE LANSBURY FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1409 ANN DORAN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 2010 ANTHONY HOPKINS FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1483 ANTHONY LAPAGLIA FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1434 BARBARA BAIN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1413 BARRY GORDON FOUNDATION: LEGACY BEN AFFLECK MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 6348 PETE HAMMOND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BEN COOPER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8697 DAVIDSON LLOYD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1486 BEN KINGSLEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1500 BENICIO DEL TORO FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1674 BETTY GARRETT FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1416 BEVERLY GARLAND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL AND SUSAN SEAFORTH SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1843 HAYES FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL PAXTON MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7019 JENELLE RILEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS -

Clint Eastwood Still America's Favorite Film Star

The @arris Poll THE HARRIS POLL 1994 #70 For release: Monday, October 3 1, 1994 CLINT EASTWOOD STILL AMERICA'S FAVORITE FILM STAR Me1 Gibson number one among women and the younger set by Humphrey Taylor For the second year running, Clint Eastwood tops the list of America's favorite film stars, followed, as he was last year, by John Wayne. Underneath the top two there is some movement; Me1 Gibson moves up from number five to number three; Harrison Ford moves up from number seven to number four; Tom Hanks, who was not in the top ten last year, jumps up to number five. The losers are Tom Cruise, who drops from number four last year to number eight this year, Arnold Schwarzenegger who drops from number three to number six, and Burt Reynolds and Jack Nicholson, who both drop out of the top ten. Me1 Gibson is the number one choice of women and of people aged 18 to 29 -- who go to the movies much more often than older Americans. John Wayne is still number one among people aged 65 and over. Denzel Washington is preferred by African Americans, and Hispanics choose Arnold Schwarzenegger as their favorite. These are the results of a nationwide Harris Poll of 1,250 adults surveyed between September 17 and 2 1. Humphrey Taylor is the Chairman and CEO of Louis Harris and Associates, lnc. ( Louis Harris & Associates 111 Fifth Avenue NYC (212) 539-9697 TABLE 1 FAVORITE FILM STAR "Who is your favorite film star?" Clint Eastwood (1) John Wayne (2) Me1 Gibson (5) Harrison Ford (7) Tom Hanks Arnold Schwarzenegger (3) Kevin Costner (6) Tom Cruise (4) Robert Redford (8) Steven Segal Dropped out of top 10: Burt Reynolds (9), Jack Nicholson (10) NOTE: Position last year in parenthesis.