Blurred Lines Between Role and Reality: a Phenomenological Study of Acting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

07 Requirements What About RFP/RFB/Rfis?

CMPSCI520/620 07 Requirements & UML Intro 07 Requirements SW Requirements Specification • Readings • How do we communicate the Requirements to others? • [cK99] Cris Kobryn, Co-Chair, “Introduction to UML: Structural and Use Case Modeling,” UML Revision Task Force Object Modeling with OMG UML Tutorial • It is common practice to capture them in an SRS Series © 1999-2001 OMG and Contributors: Crossmeta, EDS, IBM, Enea Data, • But an SRS doesn’t need to be a single paper document Hewlett-Packard, IntelliCorp, Kabira Technologies, Klasse Objecten, Rational Software, Telelogic, Unisys http://www.omg.org/technology/uml/uml_tutorial.htm • Purpose • [OSBB99] Gunnar Övergaard, Bran Selic, Conrad Bock and Morgan Björkande, “Behavioral Modeling,” UML Revision Task Force, Object Modeling with OMG UML • Contractual requirements Tutorial Series © 1999-2001 OMG and Contributors: Crossmeta, EDS, IBM, Enea elicitation Data, Hewlett-Packard, IntelliCorp, Kabira Technologies, Klasse Objecten, Rational • Baseline Software, Telelogic, Unisys http://www.omg.org/technology/uml/uml_tutorial.htm • for evaluating subsequent products • [laM01] Maciaszek, L.A. (2001): Requirements Analysis and System Design. • for change control requirements Developing Information Systems with UML, Addison Wesley Copyright © 2000 by analysis Addison Wesley • Audience • [cB04] Bock, Conrad, Advanced Analysis and Design with UML • Users, Purchasers requirements http://www.kabira.com/bock/ specification • [rM02] Miller, Randy, “Practical UML: A hands-on introduction for developers,” -

Course Outline

Degree Applicable Glendale Community College April, 2003 COURSE OUTLINE Theatre Arts 163 Acting Styles Workshop in Contemporary Theatre Production I. Catalog Statement Theatre Arts 163 is a workshop in acting styles designed to support contemporary theatre production. The students enrolled in this course will be formed into a company to present contemporary plays as a part of the season in the Theatre Arts Department at Glendale Community College. Each student will be assigned projects in accordance with his or her interests and talents. The projects will involve some phase of theatrical production as it relates to performance skills in the style of Contemporary World Theatre. Included will be current or recent successful stage play scripts from Broadway, Off-Broadway, West-end London, and other world theatre centers and date back to the style changes in realism in the mid-to-late 1950’s. The rehearsal laboratory consists of 10-15 hours per week. Units -- 1.0 – 3.0 Lecture Hours -- 1.0 Total Laboratory Hours -- 3.0 – 9.0 (Faculty Laboratory Hours -- 3.0 – 9.0 + Student Laboratory Hours -- 0.0 = 3.0 – 9.0 Total Laboratory Hours) Prerequisite Skills: None Note: This course may be taken 4 times; a maximum of 12 units may be earned. II. Course Entry Expectations Skills Expectations: Reading 5; Writing 5; Listening-Speaking 5; Math 1. III. Course Exit Standards Upon successful completion of the required course work, the student will be able to: 1. recognize the professional responsibilities of a producing group associated with the audition, preparation, and performance of a theatre production before a paying, public audience; 2. -

Chapter 4: Acting

096-157 CH04-861627 12/4/03 12:01 AM Page 96 CHAPTER ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ 4 Acting No role is too small. In this scene from Julius Caesar, the varied responses of the crowd members to Caesar’s death give the scene more depth. One can see Mark Antony, played by Al Pacino, judging the crowd’s mood and planning how to manipulate it. cting is a question of absorbing other Apeople’s personalities and adding some of our own experience. —PAUL NEWMAN, ACTOR 96 096-157 CH04-861627 12/4/03 12:02 AM Page 97 SETTING THE SCENE Focus Questions What special terminology is used in acting? What are the different types of roles? How do you create a character? What does it mean to act? Vocabulary emotional or straight parts master gesture subjective acting character parts inflection technical or objective acting characterization subtext leading roles primary source substitution protagonist secondary sources improvisation antagonist body language paraphrasing supporting roles So now you’re ready to act! For most students of drama, this is the moment you have been waiting for. You probably share the dream of every actor to create a role so convincing that the audience totally accepts your character as real, for- getting that you are only an actor playing a part. You must work hard to be an effective actor, but acting should never be so real that the audience loses the theatrical illu- sion of reality. Theater is not life, and acting is not life. Both are illusions that are larger than life. -

TRAINING the YOUNG ACTOR: a PHYSICAL APPROACH a Thesis

TRAINING THE YOUNG ACTOR: A PHYSICAL APPROACH A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Anthony Lewis Johnson December, 2009 TRAINING THE YOUNG ACTOR: A PHYSICAL APPROACH Anthony Lewis Johnson Thesis Approved: Accepted: __________________________ __________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Mr. James Slowiak Dr. Dudley Turner __________________________ __________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. Durand Pope Dr. George R. Newkome __________________________ __________________________ School Director Date Mr. Neil Sapienza ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION TO TRAINING THE YOUNG ACTOR: A PHYSICAL APPROACH...............................................................................1 II. AMERICAN INTERPRETATIONS OF STANISLAVSKI’S EARLY WORK .......5 Lee Strasberg .............................................................................................7 Stella Adler..................................................................................................8 Robert Lewis...............................................................................................9 Sanford Meisner .......................................................................................10 Uta Hagen.................................................................................................11 III. STANISLAVSKI’S LATER WORK .................................................................13 Tension -

Sysml, the Language of MBSE Paul White

Welcome to SysML, the Language of MBSE Paul White October 8, 2019 Brief Introduction About Myself • Work Experience • 2015 – Present: KIHOMAC / BAE – Layton, Utah • 2011 – 2015: Astronautics Corporation of America – Milwaukee, Wisconsin • 2001 – 2011: L-3 Communications – Greenville, Texas • 2000 – 2001: Hynix – Eugene, Oregon • 1999 – 2000: Raytheon – Greenville, Texas • Education • 2019: OMG OCSMP Model Builder—Fundamental Certification • 2011: Graduate Certification in Systems Engineering and Architecting – Stevens Institute of Technology • 1999 – 2004: M.S. Computer Science – Texas A&M University at Commerce • 1993 – 1998: B.S. Computer Science – Texas A&M University • INCOSE • Chapters: Wasatch (2015 – Present), Chicagoland (2011 – 2015), North Texas (2007 – 2011) • Conferences: WSRC (2018), GLRCs (2012-2017) • CSEP: (2017 – Present) • 2019 INCOSE Outstanding Service Award • 2019 INCOSE Wasatch -- Most Improved Chapter Award & Gold Circle Award • Utah Engineers Council (UEC) • 2019 & 2018 Engineer of the Year (INCOSE) for Utah Engineers Council (UEC) • Vice Chair • Family • Married 14 years • Three daughters (1, 12, & 10) 2 Introduction 3 Our Topics • Definitions and Expectations • SysML Overview • Basic Features of SysML • Modeling Tools and Techniques • Next Steps 4 What is Model-based Systems Engineering (MBSE)? Model-based systems engineering (MBSE) is “the formalized application of modeling to support system requirements, design, analysis, verification and validation activities beginning in the conceptual design phase and continuing throughout development and later life cycle phases.” -- INCOSE SE Vision 2020 5 What is Model-based Systems Engineering (MBSE)? “Formal systems modeling is standard practice for specifying, analyzing, designing, and verifying systems, and is fully integrated with other engineering models. System models are adapted to the application domain, and include a broad spectrum of models for representing all aspects of systems. -

Method Acting Myths

Transcription of podcast: Method Acting Myths Brian Timoney with Joe Ferrera July 2016 Debunking the myths: A look at what Method Acting is really all about Brian and Joe discuss their take on some of the myths surrounding Method Acting, with a look at the idea of actors going to extremes for roles – with examples from some of today’s acting greats – and why The Method goes much deeper than gaining weight and pulling teeth! 10 things you will learn about: • Method Acting – Is it really all about gaining weight & pulling teeth? • What do Method Acting and baking a cake have in common? • Expanding on art – The creative side of acting • How the acting greats do it: De Niro, Day-Lewis, Streep, Jolie • The process: Getting it right – Step by step • The Method: 30 years’ experience condensed into a year • Why it’s not all fun: The hard graft and boring stuff • How Lee Strasburg got it just right • The Method and depth of characterisation • Is anyone a born actor? Learning to be a natural Page 2 Full Transcript One man – One mission: To rid the world of low-standard and mediocre acting, once and for all. Brian Timoney, the world’s leading authority on Method Acting, brings you powerful, impactful, volcanic acting and ‘business of acting’ techniques in his special Acting Podcasts. It’s Brian Timoney’s World of Acting – unplugged and unleashed. Brian: Hi everyone, it’s Brian here. Welcome onto today’s podcast. And I have Joe with me – welcome, Joe. Joe: Thank you very much for having me, Brian. -

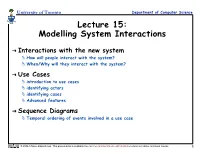

Modelling Interactions

University of Toronto Department of Computer Science Lecture 15: Modelling System Interactions Interactions with the new system How will people interact with the system? When/Why will they interact with the system? Use Cases introduction to use cases identifying actors identifying cases Advanced features Sequence Diagrams Temporal ordering of events involved in a use case © 2004-5 Steve Easterbrook. This presentation is available free for non-commercial use with attribution under a creative commons license. 1 University of Toronto Department of Computer Science Moving towards specification What functions will the new system provide? How will people interact with it? Describe functions from a user’s perspective UML Use Cases Used to show: the functions to be provided by the system which actors will use which functions Each Use Case is: a pattern of behavior that the new system is required to exhibit a sequence of related actions performed by an actor and the system via a dialogue. An actor is: anything that needs to interact with the system: a person a role that different people may play another (external) system. © 2004-5 Steve Easterbrook. This presentation is available free for non-commercial use with attribution under a creative commons license. 2 University of Toronto Department of Computer Science Use Case Diagrams Capture the relationships between actors and Use Cases Change a client contact Campaign Staff contact Manager Add a new client Record client payment Accountant © 2004-5 Steve Easterbrook. This presentation is available free for non-commercial use with attribution under a creative commons license. 3 University of Toronto Department of Computer Science Notation for Use Case Diagrams Use case Change client contact Staff contact Actor Communication association System boundary © 2004-5 Steve Easterbrook. -

Editors' Preface Introduction

Notes Editors’ Preface 1. Carey, Susan. The Origin of Concepts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009, 4. 2. See Zunshine, Lisa. “What is Cognitive Cultural Studies?” Introduction to Cognitive Cultural Studies. Ed. Lisa Zunshine. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1. Introduction 1. Deborah Mayo, Interview with John Lutterbie, Stony Brook University, tape recording, July 3, 2003. 2. Ibid. 3. Margarita Espada, Interview with John Lutterbie, Stony Brook University, tape recording, June 30, 2003. 4. Ibid. 5. Ibid. 6. Margarita Espada, Interview with John Lutterbie, Stony Brook University, tape recording, February 4, 2002. 7. I bid. 8. Deborah Mayo, Interview with John Lutterbie, Stony Brook University, tape recording, December 5, 2001. 9. Ibid. 10. Ibid. 11. Deborah Mayo, Interview with John Lutterbie, Stony Brook University, tape recording, November 7, 2001. 12. See Patrice Pavis, Theatre at the Crossroads of Culture (London and New York: Routledge, 1991), 178–209. 13. Hubert L. Dreyfus and Stuart E. Dreyfus. Mind Over Machine: The Power of Human Intuition and Expertise in the Era of the Computer (New York: Free Press, 1986), 50. 14. Ibid., 30. 15. Ibid., 30–31. 16. Neil Young, “Harvest Moon.” http://www.lyricsfreak.com/n /neil+young/harvest+moon_20099104.html. March 14, 2011 234 NOTES 1 The Language of Acting 1. I saw an Irish dance performance in which a fiddler was given a standing ovation despite the obvious fact that the instrument had no strings . 2. See Helga Noice and Tony Noice. “Two Approaches to Learning a Theatrical Script.” Memory. 4, no. 1 (1996): 1–17; and Helga Noice and Tony Noice. -

Rehearsing Emotions the Process of Creating a Role for the Stage

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS STOCKHOLMIENSIS Stockholm Studies in Sociology New series 45 Rehearsing Emotions The Process of Creating a Role for the Stage Stina Bergman Blix ©Stina Bergman Blix and Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis, Stockholm 2010 ISSN 0491-0885 ISBN 978-91-86071-41-7 Printed in Sweden by Universitetsservice US-AB, Stockholm 2010 Distributor: eddy.se ab, Visby, Sweden Front cover photos: To the left: An actor displaying grief by G.B. Duchenne, taken from “The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals” by Charles Darwin (1872), reproduced by Jens Östman. To the right: An actor displaying grief © Stina Bergman Blix. In memory of my beloved sister Clara Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................... xi Introduction ..................................................................................................1 1. Stage Actors, Roles and Emotions......................................................7 Dramaturgical Theory .................................................................................................7 Playing and Playing at ...........................................................................................8 The Relationship between Actor and Character ............................................10 Emotion Work in Role Playing............................................................................12 Double Agency ......................................................................................................19 Emotion Theory..........................................................................................................23 -

Emotion, Action and the Journey of Feelings in the Actor's Mournful

The Lamenting Brain: Emotion, Action and the Journey of Feelings in the Actor’s Mournful Art Panagiotis Papageorgopoulos Department of Drama and Theatre Royal Holloway College University of London Submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2009 Page | 1 I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the qualification of any other degree or diploma of a University or other institution of higher learning, except where due acknowledgment has been made in the text. 1/12/2009 Panagiotis Papageorgopoulos Page | 2 ABSTRACT This thesis is motivated by the question of how and why actors perform and experience emotion, especially in cases when the emotional demands are as extreme and urgent as in Greek tragedy. In order to answer this question the thesis embarks on two main tasks: (a) to reappraise the position, function and technique of emotion in the work of four key practitioners of twentieth century Western acting (Stanislavski, Meyerhold, Brecht and Grotowski) from the point of view of contemporary neuroscience, and (b) to trace their original paradigm in the professional mourners’ psychotechnique of emotion, as found in ancient and modern Greek ritual lamentation for the dead. The first part of the thesis attempts to reread and reframe twentieth century western acting’s technique of emotion by adopting the radically new neuroscientific paradigm of emotion, which reappraises emotion as a catalytic faculty in the formation of motivation, decision-making, reasoning, action and social interaction. -

The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre's 1923 And

CULTURAL EXCHANGE: THE ROLE OF STANISLAVSKY AND THE MOSCOW ART THEATRE’S 1923 AND1924 AMERICAN TOURS Cassandra M. Brooks, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Olga Velikanova, Major Professor Richard Golden, Committee Member Guy Chet, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Brooks, Cassandra M. Cultural Exchange: The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre’s 1923 and 1924 American Tours. Master of Arts (History), August 2014, 105 pp., bibliography, 43 titles. The following is a historical analysis on the Moscow Art Theatre’s (MAT) tours to the United States in 1923 and 1924, and the developments and changes that occurred in Russian and American theatre cultures as a result of those visits. Konstantin Stanislavsky, the MAT’s co-founder and director, developed the System as a new tool used to help train actors—it provided techniques employed to develop their craft and get into character. This would drastically change modern acting in Russia, the United States and throughout the world. The MAT’s first (January 2, 1923 – June 7, 1923) and second (November 23, 1923 – May 24, 1924) tours provided a vehicle for the transmission of the System. In addition, the tour itself impacted the culture of the countries involved. Thus far, the implications of the 1923 and 1924 tours have been ignored by the historians, and have mostly been briefly discussed by the theatre professionals. This thesis fills the gap in historical knowledge. -

Robert Downey Jr

PVR MOVIES FIRST VOL. 27 YOUR WINDOW INTO THE WORLD OF CINEMA JANUARY 2018 20 LITTLE-KNOWN THINGS ABOUt…. GUEST RVIEW ROBERT INTE DOWNEY JR. RAJ NEE EY PAND THE BEST NEW MOVIES PLAYING THIS MONTH: MUKKABAAZ, THE POST, 1921, 12 STRONG, PITCH PERFECT 3 GREETINGS ear Movie Lovers, We rewind to “ Scent of a Woman, “ the 1992 film that earned Al Pacino his first Oscar for his portrayal of a Here’s the January edition of Movies First, your exclusive cantankerous colonel. window to the world of cinema. T race the fast-rising career graph of American writer- Th e year kickstarts with “ Paddington 2”, a fabulous follow director Alex Garland , and join us in wishing superstar up to Paul King’s superhit animation comedy. Watch Nicholas Cage a Happy Birthday. out for Hugh Grant’s scene-stealing turn as an appalling villain, and the non-stop side-splitting gags. We really hope you enjoy the issue. Wish you a fabulous month of movie watching. Neeraj Pandey’s much awaited “Aiyaary” arrives on screen, and we have the man himself telling us what to Regards expect from this intense patriotic thriller. Akshay Kumar plays “ Pad Man ,” which tackles a bold and beautiful Gautam Dutta social subject. CEO, PVR Limited USING THE MAGAZINE We hope youa’ll find this magazine easy to use, but here’s a handy guide to the icons used throughout anyway. You can tap the page once at any time to access full contents at the top of the page. PLAY TRAILER SET REMINDER BOOK TICKETS SHARE PVR MOVIES FIRST PAGE 2 CONTENTS This January everyone’s favourite bear is back for seconds.