Editors' Preface Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blurred Lines Between Role and Reality: a Phenomenological Study of Acting

Antioch University AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive Student & Alumni Scholarship, including Dissertations & Theses Dissertations & Theses 2019 Blurred Lines Between Role and Reality: A Phenomenological Study of Acting Gregory Hyppolyte Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://aura.antioch.edu/etds Part of the Psychology Commons BLURRED LINES BETWEEN ROLE AND REALITY: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL STUDY OF ACTING A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Antioch University Santa Barbara In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY In CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY by GREGORY HIPPOLYTE BROWN August 2019 This dissertation, by Gregory Hippolyte Brown, has been approved by the committee members signed below who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of Antioch University Santa Barbara in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Committee: _________________________ Brett Kia-Keating, Ed.D. Chairperson __________________________ Sharleen O‘ Brien, Ph.D. Second Faculty __________________________ Thalia R. Goldstein, Ph.D. External Expert ii Copyright © 2019 Gregory Hippolyte Brown iii Abstract When an actor plays a character in a film, they try to connect with the emotions and behavioral patterns of the scripted character. There is an absence of literature regarding how a role influences an actor’s life before, during, and after film production. This study examined how acting roles might influence an actor during times on set shooting a movie or television series as well as their personal life after the filming is finished. Additionally the study considered the psychological impact of embodying a role, and whether or not an actor ever has the feeling that the performed character has independent agency over the actor. -

Chapter 4: Acting

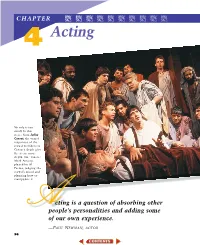

096-157 CH04-861627 12/4/03 12:01 AM Page 96 CHAPTER ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ 4 Acting No role is too small. In this scene from Julius Caesar, the varied responses of the crowd members to Caesar’s death give the scene more depth. One can see Mark Antony, played by Al Pacino, judging the crowd’s mood and planning how to manipulate it. cting is a question of absorbing other Apeople’s personalities and adding some of our own experience. —PAUL NEWMAN, ACTOR 96 096-157 CH04-861627 12/4/03 12:02 AM Page 97 SETTING THE SCENE Focus Questions What special terminology is used in acting? What are the different types of roles? How do you create a character? What does it mean to act? Vocabulary emotional or straight parts master gesture subjective acting character parts inflection technical or objective acting characterization subtext leading roles primary source substitution protagonist secondary sources improvisation antagonist body language paraphrasing supporting roles So now you’re ready to act! For most students of drama, this is the moment you have been waiting for. You probably share the dream of every actor to create a role so convincing that the audience totally accepts your character as real, for- getting that you are only an actor playing a part. You must work hard to be an effective actor, but acting should never be so real that the audience loses the theatrical illu- sion of reality. Theater is not life, and acting is not life. Both are illusions that are larger than life. -

Rehearsing Emotions the Process of Creating a Role for the Stage

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS STOCKHOLMIENSIS Stockholm Studies in Sociology New series 45 Rehearsing Emotions The Process of Creating a Role for the Stage Stina Bergman Blix ©Stina Bergman Blix and Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis, Stockholm 2010 ISSN 0491-0885 ISBN 978-91-86071-41-7 Printed in Sweden by Universitetsservice US-AB, Stockholm 2010 Distributor: eddy.se ab, Visby, Sweden Front cover photos: To the left: An actor displaying grief by G.B. Duchenne, taken from “The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals” by Charles Darwin (1872), reproduced by Jens Östman. To the right: An actor displaying grief © Stina Bergman Blix. In memory of my beloved sister Clara Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................... xi Introduction ..................................................................................................1 1. Stage Actors, Roles and Emotions......................................................7 Dramaturgical Theory .................................................................................................7 Playing and Playing at ...........................................................................................8 The Relationship between Actor and Character ............................................10 Emotion Work in Role Playing............................................................................12 Double Agency ......................................................................................................19 Emotion Theory..........................................................................................................23 -

Stanislavsky an Introduction – Jean Benedetti

Jean Benedetti was born in 1930 and educated in England and France. He trained as an actor and teacher at the Rose Bruford College of Speech and Drama, returning in 1970 as Principal of the College until 1987. He is author of a number of semi-documentary television plays. His published translations include Brecht’s Edward II and A Respectable Wedding and Georges Michel’s A Sunday Walk. His first book was a biography of Gilles de Rais. In 1982 he published the first edition of Stanislavski: An Introduction, which has been reprinted many times. Stanisla- vski: A Biography was first published in 1988 and then revised and expanded. He subsequently published The Moscow Art Theatre Letters in 1991 and Dear Writer … Dear Actress, the love letters of Anton Chekhov and Olga Knipper, in 1997. Stanislavski and the Actor, an account of Stanislavski’s teaching in the last three years of his life, followed in 1998. From 1979 to 1987 he was chairman of the Theatre Education Committee of the International Theatre Insti- tute (UNESCO). He is currently Honorary Professor at both Rose Bruford College and Queen Margaret University College Edinburgh. Books by Stanislavski AN ACTOR PREPARES AN ACTOR’S HANDBOOK BUILDING A CHARACTER CREATING A ROLE MY LIFE IN ART STANISLAVSKI IN REHEARSAL STANISLAVSKI’S LEGACY STANISLAVSKI ON OPERA Books by Jean Benedetti STANISLAVSKI: HIS LIFE AND ART STANISLAVSKI & THE ACTOR THE MOSCOW ART THEATRE LETTERS DEAR WRITER, DEAR ACTRESS: THE LOVE LETTERS OF ANTON CHEKHOV AND OLGA KNIPPER Stanislavski An Introduction Jean Benedetti A Theatre Arts Book Routledge New York A Theatre Arts Book Published in the USA and Canada in 2004 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 www.routledge-ny.com Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group. -

Day 11 Self Observation

Day 11 Self Observation A few weeks ago, I had surgery. During my recovery, I was paying attention to my body and all that it was going through and I was reminded just how important self-observation is for the actor. As an actor the greatest sources of information and inspiration are your life, your body, and your emotional states. You are experiencing things all the time and you must pay attention to them so you can sense how they feel and manifest themselves. This is a challenging task because we tend not to notice what is going on inside of ourselves unless things becomes extreme or chronic. So I want to encourage you to start paying attention to what is going on with you. And I want you to write it down because paying attention isn’t enough. Writing concretizes information, making it more real and useful than just looking at something and hoping that you’ll remember it. These self- observations of your experiences and emotions, physical sensations and musings, should be included in your actor’s journal where you write about all of the people and things you see that could become part of a characterization. So pay attention. Become an observer of yourself. Watch, listen, and feel what is going on inside of you and around you. By doing that you can have access to everything you will ever need as an actor. About Me Answer the following questions about yourself. Date ___________ Name ___________________________________________ Period ________ Age _______ Birth date ______________ Zodiac Sign ____________________ I was born in __________________, _____. -

Michael Chekhov and His Approach to Acting in Contemporary Performance Training Richard Solomon

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 5-2002 Michael Chekhov and His Approach to Acting in Contemporary Performance Training Richard Solomon Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Solomon, Richard, "Michael Chekhov and His Approach to Acting in Contemporary Performance Training" (2002). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 615. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/615 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. MICHAEL CHEKHOV AND HIS APPROACH TO ACTING IN CONTEMPORARY PERFORMANCE TRAINING by Richard Solomon B.A. University of Southern Maine, 1983 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Theatre) The Graduate School The University of Maine May, 2002 Advisory Committee: Tom Mikotowicz, Associate Professor of Theatre, Advisor Jane Snider, Associate Professor of Theatre Sandra Hardy, Associate Professor of Theatre MICaAEL CHEKHOV AND HIS APPROACH TO ACTING IN CONTEMPORARY PERFORMANCE TRAINING By Richard Solomon Thesis ~dhsor:Dr. Tom Mikotowicz An Abstract of the Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Theatre) May, 2002 Michael Chekhov was an actor, diuector, and teacher who was determined to develop a clear and accessible acting approach. During his lifetime, his ideas were often viewed as too radical and mystical. Over the past decade however, the Chekhov method of actor training has enjoyed an expansion of interest. -

An Actor Remembers: Memory's Role in the Training of the United States

An Actor Remembers: Memory’s Role in the Training of the United States Actor by Devin E. Malcolm B.A. in The Human Drama, Juniata College, 1997 M.A. in Theatre, Villanova University, 2002 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theatre History and Performance Studies University of Pittsburgh 2012 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by Devin E. Malcolm It was defended on November, 5th 2012 and approved by Kathleen George, PhD, Theatre Arts Bruce McConachie, PhD, Theatre Arts Edouard Machery, PhD, History and Philosophy of Science Dissertation Advisor: Attilio Favorini, PhD, Theatre Arts ii Copyright © by Devin E. Malcolm 2012 iii AN ACTOR REMEMBERS: MEMORY’S ROLE IN THE TRAINING OF THE UNITED STATES ACTOR Devin E. Malcolm, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2012 This dissertation examines the different ways actor training techniques in the United States have conceived of and utilized the actor’s memory as a means of inspiring the actor’s performance. The training techniques examined are those devised and taught by Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler, Joseph Chaikin, Stephen Wangh and Anne Bogart and Tina Landau. As I shall illustrate, memory is not the unified phenomenon that we often think and experience it to be. The most current research supports the hypothesis that the human memory is composed of five distinctly different, yet interrelated systems. Of these five my research focuses on three: episodic, semantic, and procedural. -

The Vocabulary of Acting: a Study of the Stanislavski 'System' in Modern

THE VOCABULARY OF ACTING: A STUDY OF THE STANISLAVSKI ‘SYSTEM’ IN MODERN PRACTICE by TIMOTHY JULES KERBER A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS BY RESEARCH Department of Drama and Theatre Arts College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis aims to examine the extent to which the vocabulary of acting created by Konstantin Stanislavski is recognized in contemporary American practice as well as the associations with the Stanislavski ‘system’ held by modern actors in the United States. During the research, a two-part survey was conducted examining the actor’s processes while creating a role for the stage and their exposure to Stanislavski and his written works. A comparison of the data explores the contemporary American understanding of the elements of the ‘system’ as well as the disconnect between the use of these elements and the stigmas attached to Stanislavski or his ‘system’ in light of misconceptions or prejudices toward either. Keywords: Stanislavski, ‘system’, actor training, United States Experienced people understood that I was only advancing a theory which the actor was to turn into second nature through long hard work and constant struggle and find a way to put it into practice. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College The

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE ACTING SYSTEM OF KONSTANTIN STANISLAVSKI AS APPLIED TO PIANO PERFORMANCE A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By ANDREA V. JOHNSON Norman, Oklahoma 2019 THE ACTING SYSTEM OF KONSTANTIN STANISLAVSKI AS APPLIED TO PIANO PERFORMANCE A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY THE COMMITTEE CONSISTING OF Dr. Barbara Fast, Chair Dr. Jane Magrath, Co-Chair Dr. Eugene Enrico Dr. Igor Lipinski Dr. Rockey Robbins Dr. Click here to enter text. © Copyright by ANDREA V. JOHNSON 2019 All Rights Reserved. AKNOWLEDGMENTS The completion of this document and degree would have been impossible without the guidance and support of my community. Foremost, I wish to express my gratitude to my academic committee including current and past members: Dr. Jane Magrath, Dr. Barbara Fast, Dr. Eugene Enrico, Dr. Igor Lipinski, Dr. Caleb Fulton, and Dr. Rockey Robbins. Dr. Magrath, thank you for your impeccable advice, vision, planning, and unwavering dedication to my development as a pianist and teacher. You left no stone unturned to ensure that I had the support necessary for success at OU and I remain forever grateful to you for your efforts, your kindness, and your commitment to excellence. My heartfelt thanks to Dr. Fast for serving as chair of this committee, for your support throughout the degree program, and for many conversations with valuable recommendations for my professional development. Dr. Enrico, thank you for your willingness to serve on my committee and for your suggestions for the improvement of this document. -

Theatre Practitioner Grudge Match – Brecht Vs Stanislavksi

Stanislavki vs Brecht Practitioner Dance-Off Konstantin Sergeievich Stanislavski (1863 - 1938) Russia Bertolt Brecht (1898 - 1956) Germany Stanislavski Engaged in and encouraged a realistic style of acting. Focused on ‘truth’ in performance for the actor and created “The System” for acting Work gave rise to the Naturalism and Realism waves of theatre “When we are on stage, we are in the here and now” Brecht Encouraged an epic and absurd style of acting. Epic Theatre focused on the audience’s experience of the performance Work inspired movements including absurdism and Theatre of Cruelty Work was politically motivated “Art is not a mirror held up to reality but a hammer with which to shape it.” “Remember: there are no small parts, only small actors.” Actors inhabit the role they are playing. Needed to understand the motivation but also the detail of the character’s lives. Texts include: An Actor Prepares, Building a Character, Creating a Role. Realism - portray real life on stage. Naturalism - characters are formed by what they’ve inherited from family and environment. Presence of the 4th wall Everyday conversations/style of speaking Ordinary people Real settings The System Given circumstances - information about the character that you start off with and the play as a whole. Emotional memory - using past experience to ‘borrow’ feelings to bring a role to life. Method of physical actions - mime brushing your teeth. Now brush your teeth whilst thinking about how to tell your lover that you’re leaving them. Subtext - meaning and motivation behind the lines. Someone saying “I love you” to someone brushing their teeth will be different if they think they’re about to be left by that person. -

Applying Constantin Stanislavski's Acting 'System'

APPLYING CONSTANTIN STANISLAVSKI’S ACTING ‘SYSTEM’ TO CHORAL REHEARSALS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF ARTS BY BOGDAN ANDREI MINUT DISSERTATION ADVISOR: DUANE KARNA BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2009 ii Copyright © 2009 by Bogdan Andrei Minut All rights reserved iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my doctoral committee members, Dr. Duane Karna, Dr. Douglas Amman, Dr. James Helton, Dr. Jody Nagel, and Dr. Elizabeth Bremigan, as well as former committee member Dr. Jeffrey Carter, for their guidance and support throughout my doctoral studies at Ball State University. Special thanks go to Dr. Jeffrey Pappas, former Director of Choral Activities, for his support of my research and for allowing me to work with his student ensemble on this study, to Dr. Kirby Koriath and Dr. Linda Pohly, former and present Coordinators of Graduate Studies in Music, respectively, for their constant care and support, and to Mrs. Linda Elliott for her administrative work. The talented singers of the Ball State University Chamber Choir, including Assistant Director and accompanist (now) Dr. Jill Burleson, and of the Concert Choir played a major role in this research and I want to thank them all for their patience, understanding, and willingness to try something a little different. I would also like to express my deep appreciation for the life, work, and artistry of Constantin Stanislavski who gave so much in particular to the art of the theater but also to all performing arts in general. His vision and ideals of true art are inspiring to me. -

RICHARD SCHECHNER and the Perforl^IANCE GROUP: a STUDY

RICHARD SCHECHNER AND THE PERFORl^IANCE GROUP: A STUDY OF ACTING TECHNIQUE AND METHODOLOGY by ESTHER SUNDELL LICHTI, B.A., A.M. A DISSERTATION IN THEATRE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 1986 ego r3 copyright 1986 Esther Sundell Lichti T'3 C^^^» -^ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am deeply indebted to Professor Richard A. Weaver and to the other members of my committee. Professors Clifford A. Ashby, Michael C. Gerlach, Daniel 0. Nathan, and Steven Paxton, for their encouragement and helpful criticism. I would also like to thank Richard Schechner for his time and generosity. This study was funded in part by the Paul Whitfield Horn Fellowship made possible by the Texas Tech University Women's Club and the University Quarterly Club. Finally, I am grateful for the love and support I have received from my fellow students, my friends, and my family. Ill ABSTRACT The social and cultural upheaval of the 1960s spawned a wide range of "alternative" theatre companies concerned with finding a solution to what they perceived as the imminent death of theatre in the United States. The Performance Group, under the direction of Richard Schechner, proved one of the most important. The study is presented in three sections. Section one sets forth the history of TPG, the theory of environmental theatre, and a study of influences upon the company's work. Section two examines the productions Dionysus in 69, Makbeth, and Commune with regard to their development from the inital idea through performance, including descriptions of the physical environments, acting problems, and performance methodology.