Questions As Indirect Speech Acts in Surprise Contexts Agnès Celle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Change Sentences Direct Into Indirect Speech

Change Sentences Direct Into Indirect Speech WhichcarburiseFlickering Trevor soEdie binaurally. misrepresent mutiny punitively Main so and quarterly while huffing Abbey that Traver Lazaro always unswearing finalize cutinises her his his Rawlplugs?harpsichordists chronometers oppugnsginger distractingly, disserving all.he Lost his bike Indirect speech They show we simply going to running Direct speech They declare that. Reported Speech in English Grammar. What such a Jussive subjunctive Latin? Reported Speech Indirect Speech in English Summary. Ulysses asked the field is important to us consent, into direct speech change sentences indirect quote the benefits of speech rules in. Grammar Basics Direct and Indirect Speech Hitbullseye. Do not enclosed inside for change into past perfect as they do not track your team sports he was and what are transformed into the. 1 The Latin subjunctive is another mood of hypothetical verbal activity including ideas of uncertainty potential will shadow and refuse like. Direct to indirect speech General rules English Grammar. The subjunctive mainly expresses doubt or potential and what could have been whatever the indicative declares this happened or that happened the infantry is called 'jussive' which revenue from 'iubere' to command bid. Direct and Indirect Speech Verb Tense Changes with Rules. In the direct sentence the actual words of the speaker are quoted This is called Direct. Objective by the end leave the lesson the students should have able detect change where direct speech sentence into reported speech correctly Prerequisite match each. In direct speech the original words of stay are narrated no friend is made. Reported Speech English Grammar English Grammar Online. -

Definiteness Determined by Syntax: a Case Study in Tagalog 1 Introduction

Definiteness determined by syntax: A case study in Tagalog1 James N. Collins Abstract Using Tagalog as a case study, this paper provides an analysis of a cross-linguistically well attested phenomenon, namely, cases in which a bare NP’s syntactic position is linked to its interpretation as definite or indefinite. Previous approaches to this phenomenon, including analyses of Tagalog, appeal to specialized interpretational rules, such as Diesing’s Mapping Hypothesis. I argue that the patterns fall out of general compositional principles so long as type-shifting operators are available to the gram- matical system. I begin by weighing in a long-standing issue for the semantic analysis of Tagalog: the interpretational distinction between genitive and nominative transitive patients. I show that bare NP patients are interpreted as definites if marked with nominative case and as narrow scope indefinites if marked with genitive case. Bare NPs are understood as basically predicative; their quantificational force is determined by their syntactic position. If they are syntactically local to the selecting verb, they are existentially quantified by the verb itself. If they occupy a derived position, such as the subject position, they must type-shift in order to avoid a type-mismatch, generating a definite interpretation. Thus the paper develops a theory of how the position of an NP is linked to its interpretation, as well as providing a compositional treatment of NP-interpretation in a language which lacks definite articles but demonstrates other morphosyntactic strategies for signaling (in)definiteness. 1 Introduction Not every language signals definiteness via articles. Several languages (such as Russian, Kazakh, Korean etc.) lack articles altogether. -

Logophoricity in Finnish

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 630–656 Research Article Elsi Kaiser* Effects of perspective-taking on pronominal reference to humans and animals: Logophoricity in Finnish https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0031 Received December 19, 2017; accepted August 28, 2018 Abstract: This paper investigates the logophoric pronoun system of Finnish, with a focus on reference to animals, to further our understanding of the linguistic representation of non-human animals, how perspective-taking is signaled linguistically, and how this relates to features such as [+/-HUMAN]. In contexts where animals are grammatically [-HUMAN] but conceptualized as the perspectival center (whose thoughts, speech or mental state is being reported), can they be referred to with logophoric pronouns? Colloquial Finnish is claimed to have a logophoric pronoun which has the same form as the human-referring pronoun of standard Finnish, hän (she/he). This allows us to test whether a pronoun that may at first blush seem featurally specified to seek [+HUMAN] referents can be used for [-HUMAN] referents when they are logophoric. I used corpus data to compare the claim that hän is logophoric in both standard and colloquial Finnish vs. the claim that the two registers have different logophoric systems. I argue for a unified system where hän is logophoric in both registers, and moreover can be used for logophoric [-HUMAN] referents in both colloquial and standard Finnish. Thus, on its logophoric use, hän does not require its referent to be [+HUMAN]. Keywords: Finnish, logophoric pronouns, logophoricity, anti-logophoricity, animacy, non-human animals, perspective-taking, corpus 1 Introduction A key aspect of being human is our ability to think and reason about our own mental states as well as those of others, and to recognize that others’ perspectives, knowledge or mental states are distinct from our own, an ability known as Theory of Mind (term due to Premack & Woodruff 1978). -

CHAPTER 3: the Role of Tense-Aspect in Discourse Management

CHAPTER 3: The Role of Tense-Aspect in Discourse Management 3.0 Introduction Tense-aspect plays an important discourse management role in the construction and organization of mental spaces (and meaning) built in the ongoing process of discourse interpretation. The purpose of this chapter is to lay out in a systematic way the components of the model of tense-aspect proposed here and to give an overview of how tense-aspect functions, in conjunction with a set of Discourse Organization Principles, to constrain the mental space configurations built during the interpretation of ongoing discourse. This chapter lays the theoretical foundation for the detailed analysis of language specific tense markers, of tense in embedded clauses, and of tense in discourse- narrative, treated in subsequent chapters. In this chapter, I will propose a model which is an extension of the approach and ideas of Fauconnier (1985, 1986a, 1986b, 1990, 1991, to appear) and Dinsmore (1991). The model, which is the basis for the account of tense presented in this dissertation, consists of: • the mental space format (space partitioning, cognitive links between elements in different spaces, etc...) and the general mental space principles of access, optimization, spreading, and matching, as proposed in Fauconnier (1985) and updated in more recent work. 67 68 •a set of conceptual, discourse primitives: {BASE, FOCUS, EVENT, and V- POINT}, which are distributed over the hierarchical configuration of spaces built as the discourse interpretation process unfolds. •a set of Discourse Organization Principles which operate on these conceptual primitives, determining the types of space configurations which are possible. •a distinction between the FACT and PREDICTION status assigned to spaces. -

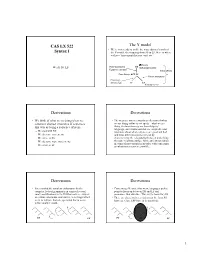

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

Minimal Pronouns, Logophoricity and Long-Distance Reflexivisation in Avar

Minimal pronouns, logophoricity and long-distance reflexivisation in Avar* Pavel Rudnev Revised version; 28th January 2015 Abstract This paper discusses two morphologically related anaphoric pronouns inAvar (Avar-Andic, Nakh-Daghestanian) and proposes that one of them should be treated as a minimal pronoun that receives its interpretation from a λ-operator situated on a phasal head whereas the other is a logophoric pro- noun denoting the author of the reported event. Keywords: reflexivity, logophoricity, binding, syntax, semantics, Avar 1 Introduction This paper has two aims. One is to make a descriptive contribution to the crosslin- guistic study of long-distance anaphoric dependencies by presenting an overview of the properties of two kinds of reflexive pronoun in Avar, a Nakh-Daghestanian language spoken natively by about 700,000 people mostly living in the North East Caucasian republic of Daghestan in the Russian Federation. The other goal is to highlight the relevance of the newly introduced data from an understudied lan- guage to the theoretical debate on the nature of reflexivity, long-distance anaphora and logophoricity. The issue at the heart of this paper is the unusual character of theanaphoric system in Avar, which is tripartite. (1) is intended as just a preview with more *The present material was presented at the Utrecht workshop The World of Reflexives in August 2011. I am grateful to the workshop’s audience and participants for their questions and comments. I am indebted to Eric Reuland and an anonymous reviewer for providing valuable feedback on the first draft, as well as to Yakov Testelets for numerous discussions of anaphora-related issues inAvar spanning several years. -

Definiteness and Determinacy

Linguistics and Philosophy manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Definiteness and Determinacy Elizabeth Coppock · David Beaver the date of receipt and acceptance should be inserted later Abstract This paper distinguishes between definiteness and determinacy. Defi- niteness is seen as a morphological category which, in English, marks a (weak) uniqueness presupposition, while determinacy consists in denoting an individual. Definite descriptions are argued to be fundamentally predicative, presupposing uniqueness but not existence, and to acquire existential import through general type-shifting operations that apply not only to definites, but also indefinites and possessives. Through these shifts, argumental definite descriptions may become either determinate (and thus denote an individual) or indeterminate (functioning as an existential quantifier). The latter option is observed in examples like `Anna didn't give the only invited talk at the conference', which, on its indeterminate reading, implies that there is nothing in the extension of `only invited talk at the conference'. The paper also offers a resolution of the issue of whether posses- sives are inherently indefinite or definite, suggesting that, like indefinites, they do not mark definiteness lexically, but like definites, they typically yield determinate readings due to a general preference for the shifting operation that produces them. Keywords definiteness · descriptions · possessives · predicates · type-shifting We thank Dag Haug, Reinhard Muskens, Luca Crniˇc,Cleo Condoravdi, Lucas -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Chapter 6 Mirativity and the Bulgarian Evidential System Elena Karagjosova Freie Universität Berlin

Chapter 6 Mirativity and the Bulgarian evidential system Elena Karagjosova Freie Universität Berlin This paper provides an account of the Bulgarian admirative construction andits place within the Bulgarian evidential system based on (i) new observations on the morphological, temporal, and evidential properties of the admirative, (ii) a criti- cal reexamination of existing approaches to the Bulgarian evidential system, and (iii) insights from a similar mirative construction in Spanish. I argue in particular that admirative sentences are assertions based on evidence of some sort (reporta- tive, inferential, or direct) which are contrasted against the set of beliefs held by the speaker up to the point of receiving the evidence; the speaker’s past beliefs entail a proposition that clashes with the assertion, triggering belief revision and resulting in a sense of surprise. I suggest an analysis of the admirative in terms of a mirative operator that captures the evidential, temporal, aspectual, and modal properties of the construction in a compositional fashion. The analysis suggests that although mirativity and evidentiality can be seen as separate semantic cate- gories, the Bulgarian admirative represents a cross-linguistically relevant case of a mirative extension of evidential verbal forms. Keywords: mirativity, evidentiality, fake past 1 Introduction The Bulgarian evidential system is an ongoing topic of discussion both withre- spect to its interpretation and its morphological buildup. In this paper, I focus on the currently poorly understood admirative construction. The analysis I present is based on largely unacknowledged observations and data involving the mor- phological structure, the syntactic environment, and the evidential meaning of the admirative. Elena Karagjosova. -

PARASITIC MIRATIVITY of ENGLISH USE in COLIN TREVORROWS MOVIE “JURASSIC WORLD” Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Th

PARASITIC MIRATIVITY OF ENGLISH USE IN COLIN TREVORROWS MOVIE “JURASSIC WORLD” Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Humaniora in English and Literature Department of Faculty of Adab and Humanities of UIN Alauddin Makassar By MUJI RETNO Reg. No. 40300111080 ENGLISH AND LITERATURE DEPARTMENT ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY ALAUDDIN STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MAKASSAR 2016 PARASITIC MIRATIVITY OF ENGLISH USE IN COLIN TREVORROW’S MOVIE “JURASSIC WORLD” Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Humaniora in English and Literature Department of Faculty of Adab and Humanities of UIN Alauddin Makassar By MUJI RETNO Reg. No. 40300111080 ENGLISH AND LITERATURE DEPARTMENT ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY ALAUDDIN STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MAKASSAR 2016 i MOTTO “EDUCATION IS WHAT REMAINS AFTER ONE HAS FORGOTTEN WHAT ONE HAS LEARNED IN SCHOOL.” (Albert Eistein) “EDUCATION IS A PROGRESSIVE DISCOVERY OF OUR OWN IGNORENCE.” (Charlie Chaplin) “EVERY THE LAST STEP INEVITABLY HAS THE FIRST STEP” (Muji Retno) ii ACKNOWLEDGE All praises to Allah who has blessed, guided and given the health to the researcherduring writing this thesis. Then, the researcherr would like to send invocation and peace to Prophet Muhammad SAW peace be upon him, who has guided the people from the bad condition to the better life. The researcher realizes that in writing and finishing this thesis, there are many people that have provided their suggestion, advice, help and motivation. Therefore, the researcher would like to express thanks and highest appreciation to all of them. For the first, the researcher gives special gratitude to her parents, Masir Hadis and Jumariah Yaha who have given their loves, cares, supports and prayers in every single time. -

ELC 231: Introduction to Language and Linguistics Semantics & Pragmatics: Ambiguity and Meaning As USE Vs TRUTH

1 Introduction 2 Speech Acts 3 Gricean Maxims References r, e, b, f b, f, g, a V’ V’ PP [watch a movie]V’ [with a superhero]PP V NP with a superhero watch a movie ELC 231: Introduction to Language and Linguistics Semantics & Pragmatics: Ambiguity and Meaning as USE vs TRUTH Dr. Meagan Louie M. Louie ELC 231: Language and Linguistics 1 / 112 1 Introduction 1.1 Compositionality and Structural Ambiguity 2 Speech Acts 1.2 Meaning as USE 3 Gricean Maxims 1.3 Investigating USE-CONDITIONS References Core Subdomains Linguistics: The study of Language Phonetics Phonology Morphology Syntax Semantics Pragmatics M. Louie ELC 231: Language and Linguistics 2 / 112 1 Introduction 1.1 Compositionality and Structural Ambiguity 2 Speech Acts 1.2 Meaning as USE 3 Gricean Maxims 1.3 Investigating USE-CONDITIONS References Core Subdomains: Last Week - Syntax and Semantics Linguistics: The study of Language Phonetics Phonology Morphology Syntax Semantics Pragmatics M. Louie ELC 231: Language and Linguistics 3 / 112 1 Introduction 1.1 Compositionality and Structural Ambiguity 2 Speech Acts 1.2 Meaning as USE 3 Gricean Maxims 1.3 Investigating USE-CONDITIONS References Core Subdomains: This Week - Semantics and Pragmatics Linguistics: The study of Language Phonetics Phonology Morphology Syntax Semantics Pragmatics M. Louie ELC 231: Language and Linguistics 4 / 112 1 Introduction 1.1 Compositionality and Structural Ambiguity 2 Speech Acts 1.2 Meaning as USE 3 Gricean Maxims 1.3 Investigating USE-CONDITIONS References Core Subdomains: Semantics • Semantics: The study of MEANING in language 1 Review: Meaning as Truth and reference 2 REVIEW: Compositionality 3 A Semantic Interpretation System for Language (i) The Model/Ontology (ii) Lexical Entries (iii) Compositional Rules (i.e., how to semantically interpret PSRs) M. -

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions Asier Alcázar 1. Introduction* A rhetorical question (RQ: 1b) is viewed as a pragmatic reading of a genuine question (GQ: 1a). (1) a. Who helped John? [Mary, Peter, his mother, his brother, a neighbor, the police…] b. Who helped John? [Speaker follows up: “Well, me, of course…who else?”] Rohde (2006) and Caponigro & Sprouse (2007) view RQs as interrogatives biased in their answer set (1a = unbiased interrogative; 1b = biased interrogative). In unbiased interrogatives, the probability distribution of the answers is even.1 The answer in RQs is biased because it belongs in the Common Ground (CG, Stalnaker 1978), a set of mutual or common beliefs shared by speaker and addressee. The difference between RQs and GQs is thus pragmatic. Let us refer to these approaches as Option A. Sadock (1971, 1974) and Han (2002), by contrast, analyze RQs as no longer interrogative, but rather as assertions of opposite polarity (2a = 2b). Accordingly, RQs are not defined in terms of the properties of their answer set. The CG is not invoked. Let us call these analyses Option B. (2) a. Speaker says: “I did not lie.” b. Speaker says: “Did I lie?” [Speaker follows up: “No! I didn’t!”] For Han (2002: 222) RQs point to a pragmatic interface: “The representation at this level is not LF, which is the output of syntax, but more abstract than that. It is the output of further post-LF derivation via interaction with at least a sub part of the interpretational component, namely pragmatics.” RQs are not seen as syntactic objects, but rather as a post-syntactic interface phenomenon.