How Far Does Scientific Community Look Back?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scientific Communities in the Developing World Scientific Communities in the Developing World

Scientific Communities in the Developing World Scientific Communities in the Developing World Edited by jacques Caillard V.V. Krishna Roland Waast Sage Publications New Delhiflhousand Oaks/London Copyright @) Jacques Gaillard, V.V. Krishna and Roland Waast, 1997. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. First published in 1997 by Sage Publications India Pvt Ltd M-32, Greater Kailash Market I New Delhi 110 048 Sage Publications Inc Sage Publications Ltd 2455 Teller Road 6 Bonhill Street Thousand Oaks, California 91320 London EC2A 4PU Published by Tejeshwar Singh for Sage Publications India Pvt Ltd, phototypeset by Pagewell Photosetters, Pondicherry and printed at Chaman Enterprises, Delhi. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Scientific communities in the developing world I edited by Jacques Gaillard, V.V. Krishna, Roland Waast. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Science-Developing countries--History. 2. Science-Social aspect- Developing countries--History. I. Gaillard, Jacques, 1951- . 11. Krishna, V.V. 111. Waast, Roland, 1940- . Q127.2.S44 306.4'5'091724--dc20 1996 9617807 ISBN: 81-7036565-1 (India-hb) &8039-9330-7 (US-hb) Sage Production Editor: Sumitra Srinivasan Contents List of Tables List of Figures Preface 1. Introduction: Scientific Communities in the Developing World Jacques Gaillard, V.V. Krishna and Roland Waast Part 1: Scientific Communities in Africa 2. Sisyphus or the Scientific Communities of Algeria Ali El Kenz and Roland Waast 3. -

The Role of Social Context in the Production of Scientific Knowledge

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 5-2015 The Role of Social Context in the Production of Scientific Knowledge Kristen Lynn Beard [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Part of the Philosophy of Science Commons Recommended Citation Beard, Kristen Lynn, "The Role of Social Context in the Production of Scientific nowledgeK " (2015). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1852 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Role of Social Context in the Production of Scientific Knowledge Kristen Lynn Beard The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Chancellor’s Honors Program Department of Philosophy Undergraduate Thesis Submitted December 8, 2014 Thesis Advisor: Dr. Nora Berenstain Beard 1 Model 1: The Influence of Social Context on the Scientific Method Beard 2 Introduction: Scientific Knowledge as Both Social and Rational A person may believe that a certain theory is true and explain that he does so, for instance, because it is the best explanation he has of the facts or because it gives him the most satisfying world picture. This does not make him irrational, but I take it to be part of empiricism to disdain such reasons. -

Bringing Science and Scientists to Life in Post-Secondary Science Education

Sci & Educ DOI 10.1007/s11191-010-9310-7 The Story Behind the Science: Bringing Science and Scientists to Life in Post-Secondary Science Education Michael P. Clough Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2010 Abstract With funding from the United States National Science Foundation, 30 histor- ical short stories designed to teach science content and draw students’ attention to the nature of science (NOS) have been created for post-secondary introductory astronomy, biology, chemistry, geology, and physics courses. The project rationale, story development and structure, and freely available stories at the project website are presented. 1 Introduction The phrase ‘‘nature of science’’ (NOS) has been used for some time, particularly in the science education community, in referring to what science is, how science works, the epistemological and ontological foundations underlying science, the culture of science, and how society both influences and reacts to scientific activities (Clough 2006). Accurately understanding the NOS is crucial for science literacy (AAAS 1989; Matthews 1994; McComas and Olson 1998; NRC 1996) and can perhaps play an important role in enticing students to further their science education. Matthews (1994), McComas et al. (1998) and others have argued that knowledge of scientists and how science works will enhance students’ understanding of science as a human endeavor; increase interest in science and science classes; improve student learning of science content; and promote better social decision-making. Morris Shamos (1995) claimed that understanding the NOS is the most important component of scientific literacy because that knowledge, accurate or not, is what citizens use when assessing public issues involving science and technology. -

How Science Works

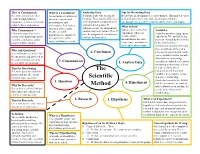

PB 1 How science works The Scientific Method is traditionally presented in the first chapter of science text- books as a simple recipe for performing scientific investigations. Though many use- ful points are embodied in this method, it can easily be misinterpreted as linear and “cookbook”: pull a problem off the shelf, throw in an observation, mix in a few ques- tions, sprinkle on a hypothesis, put the whole mixture into a 350° experiment—and voila, 50 minutes later you’ll be pulling a conclusion out of the oven! That might work if science were like Hamburger Helper®, but science is complex and cannot be re- duced to a single, prepackaged recipe. The linear, stepwise representation of the process of science is simplified, but it does get at least one thing right. It captures the core logic of science: testing ideas with evidence. However, this version of the scientific method is so simplified and rigid that it fails to accurately portray how real science works. It more accurately describes how science is summarized after the fact—in textbooks and journal articles—than how sci- ence is actually done. The simplified, linear scientific method implies that scientific studies follow an unvarying, linear recipe. But in reality, in their work, scientists engage in many different activities in many different sequences. Scientific investigations often involve repeating the same steps many times to account for new information and ideas. The simplified, linear scientific method implies that science is done by individual scientists working through these steps in isolation. But in reality, science depends on interactions within the scientific community. -

PDF Download Starting with Science Strategies for Introducing Young Children to Inquiry 1St Edition Ebook

STARTING WITH SCIENCE STRATEGIES FOR INTRODUCING YOUNG CHILDREN TO INQUIRY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Marcia Talhelm Edson | 9781571108074 | | | | | Starting with Science Strategies for Introducing Young Children to Inquiry 1st edition PDF Book The presentation of the material is as good as the material utilizing star trek analogies, ancient wisdom and literature and so much more. Using Multivariate Statistics. Michael Gramling examines the impact of policy on practice in early childhood education. Part of a series on. Schauble and colleagues , for example, found that fifth grade students designed better experiments after instruction about the purpose of experimentation. For example, some suggest that learning about NoS enables children to understand the tentative and developmental NoS and science as a human activity, which makes science more interesting for children to learn Abd-El-Khalick a ; Driver et al. Research on teaching and learning of nature of science. The authors begin with theory in a cultural context as a foundation. What makes professional development effective? Frequently, the term NoS is utilised when considering matters about science. This book is a documentary account of a young intern who worked in the Reggio system in Italy and how she brought this pedagogy home to her school in St. Taking Science to School answers such questions as:. The content of the inquiries in science in the professional development programme was based on the different strands of the primary science curriculum, namely Living Things, Energy and Forces, Materials and Environmental Awareness and Care DES Exit interview. Begin to address the necessity of understanding other usually peer positions before they can discuss or comment on those positions. -

Sacred Rhetorical Invention in the String Theory Movement

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Communication Studies Theses, Dissertations, and Student Research Communication Studies, Department of Spring 4-12-2011 Secular Salvation: Sacred Rhetorical Invention in the String Theory Movement Brent Yergensen University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstuddiss Part of the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Yergensen, Brent, "Secular Salvation: Sacred Rhetorical Invention in the String Theory Movement" (2011). Communication Studies Theses, Dissertations, and Student Research. 6. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstuddiss/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Studies, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Studies Theses, Dissertations, and Student Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SECULAR SALVATION: SACRED RHETORICAL INVENTION IN THE STRING THEORY MOVEMENT by Brent Yergensen A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: Communication Studies Under the Supervision of Dr. Ronald Lee Lincoln, Nebraska April, 2011 ii SECULAR SALVATION: SACRED RHETORICAL INVENTION IN THE STRING THEORY MOVEMENT Brent Yergensen, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2011 Advisor: Ronald Lee String theory is argued by its proponents to be the Theory of Everything. It achieves this status in physics because it provides unification for contradictory laws of physics, namely quantum mechanics and general relativity. While based on advanced theoretical mathematics, its public discourse is growing in prevalence and its rhetorical power is leading to a scientific revolution, even among the public. -

Perceptions of Science in America

PERCEPTIONS OF SCIENCE IN AMERICA A REPORT FROM THE PUBLIC FACE OF SCIENCE INITIATIVE THE PUBLIC FACE OF SCIENCE PERCEPTIONS OF SCIENCE IN AMERICA american academy of arts & sciences Cambridge, Massachusetts © 2018 by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences All rights reserved. isbn: 0-87724-120-1 This publication is available online at http://www.publicfaceofscience.org. The views expressed in this publication are those held by the contributors and are not necessarily those of the Officers and Members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Please direct inquiries to: American Academy of Arts & Sciences 136 Irving Street Cambridge ma 02138-1996 Telephone: 617-576-5000 Fax: 617-576-5050 Email: [email protected] Web: www.amacad.org CONTENTS Preface v Top Three Takeaways vii Introduction 1 SECTION 1: General Perceptions of Science 4 Confidence in Scientific Leaders Remains Relatively Stable 4 A Majority of Americans Views Scientific Research as Beneficial . 6 . But Many are Concerned about the Pace of Change 7 Americans Express Strong Support for Public Investment in Research 8 Americans Support an Active Role for Science and Scientists in Public Life 10 Scientists Should Play a Major Role in Shaping Public Policy 11 Discussion and Research Considerations 12 SECTION 2: Demographic Influences on General Views of Science 14 Confidence in Scientific Leaders Varies Based on Demographics and Other Factors 14 Higher Educational Attainment Correlates with Positive Perceptions of Science 16 Trust in Scientists Varies Based on Education and Politics 18 Discussion and Research Considerations 20 SECTION 3: Case Studies of Perceptions on Specific Science Topics 22 There is No Single Anti-Science Population . -

Total Scicomm: a Strategy for Communicating Open Science

publications Communication Total SciComm: A Strategy for Communicating Open Science Manh-Toan Ho * , Manh-Tung Ho and Quan-Hoang Vuong Centre for Interdisciplinary Social Research, Phenikaa University, Hanoi 100803, Vietnam; [email protected] (M.-T.H.); [email protected] (Q.-H.V.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This paper seeks to introduce a strategy of science communication: Total SciComm or all-out science communication. We proposed that to maximize the outreach and impact, scientists should use different media to communicate different aspects of science, from core ideas to methods. The paper uses an example of a debate surrounding a now-retracted article in the Nature journal, in which open data, preprints, social media, and blogs are being used for a meaningful scientific conversation. The case embodied the central idea of Total SciComm: the scientific community employs every medium to communicate scientific ideas and engages all scientists in the process. Keywords: preprints; open science; science communication; social media; Total SciComm 1. Introduction Growing skepticism towards scientific findings makes capturing attention from the public an urgent and serious issue for scientists. The attention will help raise the scien- Citation: Ho, M.-T.; Ho, M.-T.; tists’ profiles and provide scientists a channel to communicate through scientific ideas. Vuong, Q.-H. Total SciComm: A On YouTube, and a new form of radio—podcast—the rise of the Intellectual Dark Web Strategy for Communicating Open group is a prominent example of an effort for good and effective science communication [1]. Science. Publications 2021, 9, 31. -

The Scientific Method Is a It Is a Possible Answer and Logical Problem-Solving Explanation to Your Question Process Used by Scientists

How to Communicate What is a Conclusion? Analyzing Data Tips for Recording Data Scientist communicate their A conclusion is a statement Scientists study data to look for Record data in an organized, accurate manner. This makes it easier results through journals, based on experimental meaning. They look for differences to identify patterns/ trends, make predictions, and draw magazines, websites, television, measurements and in the dependent variable between conclusions. Use a scientific journal, tables, charts, and graphs. radio, lectures, and posters. control and test groups. If observations. It includes a What is Data? summary of the results, differences exist, the independent Data are the results of the Variables Why Communicate? whether or not the variable may have had an effect. If Communicating discoveries experiment. They can Variables are what change in an hypothesis was supported, not, the independent variable may advances the knowledge of the include number experiment. The variable being the significance of the not have had any effect. scientific community, and it measurements like time, tested or changed by the scientist study, and future research. improves future studies. temperature, and mass, or is the independent or they can be observations. manipulated variable. Normally, there is only one of these at a Why Ask Questions? time so that experimental results It is important to clearly define 6. Conclusion can be attributed to that variable. the question being answered or Dependent or responding the problem being solved by 7. Communicate variables are what the scientist is the scientific investigation. 5. Analyze Data measuring or observing. If there Tips for Questioning is a direct link between Scientific questions should be The independent and dependent narrow and specific. -

NSF Sensational 60

Cover credits Background: © 2010 JupiterImages Corporation Inset credits (left to right): Courtesy Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution; Gemini Observatory; Nicolle Rager Fuller, National Science Foundation; Zee Evans, National Science Foundation; Nicolle Rager Fuller, National Science Foundation; Zina Deretsky, National Science Foundation, adapted from map by Chris Harrison, Human-Computer Interaction Institute, Carnegie Mellon University; Tobias Hertel, Insti- tute for Physical Chemistry, University of Würzburg Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation 1 Introduction The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent federal agency that supports fundamental research and education across all fields of science and engineering. Congress passed legislation creating the NSF in 1950 and President Harry S. Truman signed that legislation on May 10, 1950, creating a government agency that funds research in the basic sciences, engineering, mathematics and technology. NSF is the federal agency responsible for nonmedical research in all fields of science, engineering, education and technology. NSF funding is approved through the federal budget process. In fiscal year (FY) 2010, its budget is about $6.9 billion. NSF has an independent governing body called the National Science Board (NSB) that oversees and helps direct NSF programs and activities. NSF funds reach all 50 states through grants to nearly 2,000 universities and institutions. NSF is the funding source for approximately 20 percent of all federally supported basic research conducted by America’s colleges and universities. Each year, NSF receives over 45,000 competitive requests for funding, and makes over 11,500 new funding awards. NSF also awards over $400 million in professional and service contracts yearly. NSF has a total workforce of about 1,700 at its Arlington, Va., headquarters, including approximately 1,200 career employees, 150 scientists from research institutions on temporary duty, 200 contract workers and the staff of the NSB office and the Office of the Inspector General. -

World Views, Paradigms, and the Practice of Social Science Research

01-Willis (Foundations)-45170.qxd 1/1/2007 12:01 PM Page 1 CHAPTER 1 World Views, Paradigms, and the Practice of Social Science Research Case 1. Quantitative Research Dr. James Jackson was concerned about whether a particular approach to teaching undergraduate courses is effective. The approach is called the per- sonalized system of instruction (PSI), developed by Fred Keller, a Columbia University psychologist and personal friend of B. F. Skinner. PSI (Martin, 1997) has been used for several decades in the sciences, but Dr. Jackson was not able to find convincing research about the suitability of PSI for humanities courses. Personalized System of Instruction (PSI) The PSI method of teaching was popular in the 1970s and is still used in many science classes. The content to be learned is divided into units or modules. Students get assignments with each module. When they think they have mastered a module, they come to class and take a test on that module. If they make 85% or more on the test, they get credit for the module and begin studying the next module. When they pass all the modules they are finished with the course and receive an A. In a course with 13 modules, anyone who completes all 13 might receive an A, students who finish 11 would receive Bs, and so on. The approach was called “personalized” because students could go at their own pace and decide when they wanted to be tested. Critics argued that PSI wasn’t very person- alized because all students had to learn the same content, which was selected by the instructor, and everyone was evaluated with the same objective tests. -

Public Understanding of Science As Seen by the Scientific Community

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 403 132 SE 059 586 AUTHOR Cobern, William W. TITLE Public Understanding of Science as Seen by the Scientific Community: Do We Need To Re-Conceptualize the Challenge and To Re-Examine Our Own Assumptions? PUB DATE 18 Nov 96 NOTE 25p.; Paper presented at the Seminar for Science, Technology and Citizenship (Leangkollen, Norway, November 18-19, 1996). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.) (120) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PCO1 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Educational Change; Elementary Secondary Education; Futures (of Society); Higher Education; *Public Opinion; *Science and Society; Science Education; Scientific Literacy; Scientists; Values IDENTIFIERS *Philosophy of Science ABSTRACT This paper addresses the question of how the scientific community views the public understanding of science and whether there needs to be a re-conceptualization of the challenge to foster the public understanding of science, as well as whether there is a need to re-examine assumptions. It is argued that the science community's historic perspective on the public is grounded in the legitimate interests of science, but that the promotion of the public understanding of science needs to be grounded in its legitimate interests in science. Topics covered include:(1) A Celebration of Science, which discusses angst in the scientific community and heroic stories of scientific investigations;(2) Anti-Science Sentiment, a phenomenon of the last 20 years;(3) Scientific Positivism, which roughly represents a classical view of realism, philosophical materialism, strict objectivity, and hypothetico-deductive method; and (4) An Alternative View of Science and the Public, where the differences between scientists' and nonscientists' views of nature and problems with the compatibility of science with very different perspectives is explained.