Thesis Hsf 2018 Sieberhagen S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stories of the South Peninsula

Stories of the South Peninsula Historical research, stories and heritage tourism opportunities in the South Peninsula AFRICANSOUTH TOURISM The peninsula from Cape Point Nature Reserve Prepared for the City of Cape Town by C. Postlethwayt, M. Attwell & K. Dugmore Ström June 2014 Making progress possible. Together. Background The primary objective of this project was to prepare a series of ‘story packages’ providing the content for historical interpretive stories of the ‘far’ South Peninsula. Stories cover the geographical area of Chapman’s Peak southwards to include Imhoff, Ocean View, Masiphumelele, Kommetjie, Witsand, Misty Cliffs and Scarborough, Plateau Road, Cape Point, Smitswinkel Bay to Miller’s Point, Boulders, Simon’s Town, Red Hill, Glencairn and Fish Hoek to Muizenberg. The purposes for which these stories are to be told are threefold, namely to support tourism development; to stimulate local interest; and to promote appropriate and sustainable protection of heritage resources through education, stimulation of interest and appropriate knowledge. To this end, the linking of historical stories and tourism development requires an approach to story-telling that goes beyond the mere recording of historic events. The use of accessible language has been a focus. Moreover, it requires an approach that both recognises the iconic, picture-postcard image of parts of Cape Town (to which tourists are drawn initially), but extends it further to address the particular genius loci that is Cape Town’s ‘Deep South’, in all its complexity and coloured by memory, ambivalences and contradictory experiences. We believe there is a need to balance the more conventional approach, which selects people or events deemed worthy of commemoration (for example, the Battle of Muizenberg) to tell the story of places, by interweaving popular memory and culture into these recordings (for example, the rich Muslim culture that existed in Simon’s Town before the removal under the Group Areas Act). -

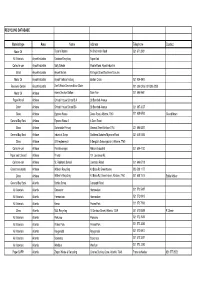

City Libraries Offering the Drop-And-Go Service 21 September

21 September 2020 City libraries offering the Drop-and-Go service Name of the Library Telephone Numbers Address Email Address Adriaanse Library 021 444 2392 Adriaanse Avenue, Elsies River 7490 [email protected] Belhar Library 021 814 1315 Blackberry Crescent, Belhar 7493 [email protected] Bellville Library 021 444 0300 Carel Van Aswegen Street, Bellville 7530 [email protected] Bellville South Library 021 951 4370 Kasselsvlei Road, Bellville South 7530 [email protected] Brackenfell Library 021 400 3806 Paradys Street, Brackenfell, 7560 [email protected] Central Library 021 444 0983 Drill Hall, Parade Street, Cape Town,8001 [email protected] Colin Eglin Sea Point Library 021 400 4184 Civic Centre, Cnr Three Anchor Bay & Main Rds, Sea Point 8001 [email protected] Crossroads Library 021 444 2533 Philippi Village, Cwangco Crescent, Philippi 7781 [email protected] Delft Library 021 400 3678 Cnr Delft & Voorbrug Road, Delft 7210 [email protected] Du Noon Library 021 400 6401/2 2 Waxberry Street, Du Noon 7441 [email protected] Durbanville Library 021 444 7070 Cnr Oxford & Koeberg Rd, Durbanville 7550 [email protected] Edgemead Library 021 444 7352 Edgemead Avenue, Edgemead 7460 [email protected] Eersterivier Library 021 444 7670 Cnr Bobs Way & Beverley Street, Eerste River 7100 [email protected] Fisantekraal Library 021 444 9259 Cnr Dullah -

Cape Town 2021 Touring

CAPE TOWN 2021 TOURING Go Your Way Touring 2 Pre-Booked Private Touring Peninsula Tour 3 Peninsula Tour with Sea Kayaking 13 Winelands Tour 4 Cape Canopy Tour 13 Hiking Table Mountain Park 14 Suggested Touring (Flexi) Connoisseur's Winelands 15 City, Table Mountain & Kirstenbosch 5 Cycling in the Winelands & visit to Franschhoek 15 Cultural Tour - Robben Island & Kayalicha Township 6 Fynbos Trail Tour 16 Jewish Cultural & Table Mountain 7 Robben Island Tour 16 Constantia Winelands 7 Cape Malay Cultural Cooking Experience 17 Grand Slam Peninsula & Winelands 8 “Cape Town Eats” City Walking Tour 17 West Coast Tour 8 Cultural Exploration with Uthando 18 Hermanus Tour 9 Cape Grace Art & Antique Tour 18 Shopping & Markets 9 Group Scheduled Tours Whale Watching & Shark Diving Tours Group Peninsula Tour 19 Dyer Island 'Big 5' Boat Ride incl. Whale Watching 10 Group Winelands Tour 19 Gansbaai Shark Diving Tour 11 Group City Tour 19 False Bay Shark Eco Charter 12 Touring with Families Family Peninsula Tour 20 Family Fun with Animals 20 Featured Specialist Guides 21 Cape Town Touring Trip Reports 24 1 GO YOUR WAY – FULL DAY OR HALF DAY We recommend our “Go Your Way” touring with a private guide and vehicle and then customizing your day using the suggested tour ideas. Cape Town is one of Africa’s most beautiful cities! Explore all that it offers with your own personalized adventure with amazing value that allows a day of touring to be more flexible. RATES FOR FULL DAY or HALF DAY– GO YOUR WAY Enjoy the use of a vehicle and guide either for a half day or a full day to take you where and when you want to go. -

CPT City of Cape Town SDBIP 2014 2015

2014 – 2015 SERVICE DELIVERY AND BUDGET IMPLEMENTATION PLAN The Service Delivery and Budget Implementation Plan for the City of Cape Town 2014/2015 MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE MAYOR We have undertaken an ambitious programme of governance in the city. That programme has been to turn the five pillars into a development programme until 2016. Those pillars are: the opportunity city; the safe city; the caring city; the inclusive city; and the well-run city. I think we have achieved a great deal. The IDP maps out our goals, plans and ambitions for the remainder of this term, which is already well under way. I believe that we have achieved something quite unique in local government in South Africa and what national legislation actually intended: the complete alignment of democratic will into a programme of government. But having put in place this great plan, we need to know that it is working. We need to see the outcomes that we are delivering to the people, for their own benefit and for our own progress reports. These outcomes must be assessed by a monitoring and evaluation framework that can help flag our priority areas and provide baselines and targets against which we measure our performance. That means having a scorecard that we can monitor, a scorecard that becomes the living document of delivery. We do operate with certain realities. The Auditor- General requires strict monitoring of things that are measurable in order to determine compliance and sound government. We support those principles but in as much as we satisfy the Auditor General, we must satisfy our own purposes too. -

I Cataloguing Practices from Creation To

Cataloguing practices from creation to use: A study of Cape Town Metropolitan Public Libraries in Western Cape Province, South Africa by Madireng Jane Monyela Student number: 215081797 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Information Studies) in the School of Social Sciences, College of Humanities, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa Supervisor: Prof. Stephen Mutula ---------------------------------------------- June, 2019 i Abstract Cataloguing is the process of creating metadata representing information sources such as books, sound recordings, digital video disks (DVDs), journals and other materials found in a library or group of libraries. This process requires the use of standardised cataloguing tools to achieve the bibliographic description, authority control, subject analysis and assignment of classification notation to generate a library catalogue. The well-generated library catalogue serves as an index of a collection of information sources found in libraries that enables the library users to discover which information sources are available and where they are in the library. Such a catalogue should provide information such as the creators’ names, titles, subject terms, standard number, publication area, physical description and notes that describe those information sources to facilitate easy information retrieval. This study sought to investigate cataloguing practices from creation to use in Cape Town Metropolitan public libraries in South Africa with the aim -

Table Mountain National Park Draft Conservation Development Framework (2006 – 2010)

TABLE MOUNTAIN NATIONAL PARK DRAFT CONSERVATION DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK (2006 – 2010) COMMENTS & RESPONSES REPORT Prepared for: South African National Parks Prepared by: iKapa Enviroplan A Setplan – DJ Environmental Consultants Joint Venture October 2006 iKAPA ENVIROPLAN Page i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................1 1.1 Background ............................................................................................1 1.2 Approach to Synthesis of Comments......................................................2 1.3 Scope, Structure and Contents of this Report ........................................3 2. STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION PROCESS.............................................4 2.1 Introduction.............................................................................................4 2.2 Notification letter & Registration Form ....................................................5 2.3 Notification Advertisement ......................................................................5 2.4 Radio Interview.......................................................................................5 2.5 Advertisement informing public of Open Days........................................6 2.5 Background Information Document ........................................................6 2.6 Public Open Days...................................................................................6 2.7 Placement of Draft CDF in Local Libraries and on SANParks Website ..7 -

Masiphumelele Offers a Broad Selection of Titles

OUTREACH MARIANNE ELLIOTT Masiphumelele offers a broad selection of titles. Regional Librarian, South The library operates as a satellite LIBRARY ofFish Hoek Library.The staff asiphumelele (previously are at present all on contract. known as Site Five) is an Thando Melamane works atthe M informal settlement situ- library every day andis assisted ated betweenthe communities of BLjSSjMS by Fish Hoekcontract staff. Fish Hoek and OceanView that Additional opening hours are came into existence in1992. funds from the OceanView LibraryTrust funded by Masiphumelele In1994 JeanWilliams, formerlibrarian of coveredsomeoftheexpenses;shelvingwas Corporation. OceanView and now director ofBiblionef, contributedby Hangberg Library; the small The library hasgone from strengthto started taking donated books to stoep was enclosed and a bench and other strength offering story-telling, school visits Masiphumelele on Thursday afternoons, items were donated. and a venue for outreach activities. Five offering passers-by the books fromthe The Western Cape Provincial Library nursery schools visit the library every bootofhercar. Service provided suitable book material. Thursday morning (more than100 Asinterestgrewandrequestsweremade Soon afterwards an official opening of the children). They exchange their books and for specific subjects, she investigated sev- Masiphumelele Community Library was listento stories. The staff attended the chil- erallocations for a more permanent venue. arranged and attended bylocal councillors. dren'sgraduation ceremonies atthe end of For sometime, she used a cornerofthe The keynote speaker wasVirginia Kasana, the year to witness the success ofthe pro- clinic in the mornings. She was now in con- the chieflibrarian from Langa Library. gramme. tact with a different section of the commu- Afterahousingdisputeon22August Lap Reading nity fromthose she had servedinthe 1999, the building was destroyed by fire. -

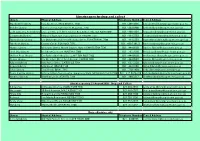

Material Type Area Name Address Telephone Contact RECYCLING DATABASE

RECYCLING DATABASE Material type Area Name Address Telephone Contact Motor Oil - Taylor's Motors 14 Chichester Road 021 671 2931 All Materials Airport Industria Rainbow Recycling Airport Ind Collect-a-can Airport Industria Solly Sebola Mobile Road, Airpot industria Metal Airport Industria Airport Metals Michigan Street/'Northern Suburbs Motor Oil Airport Industria Airport Vehicle Testing Boston Circle 021 934 4900 Recovery Centre Airport Industria Don't Waste Services Brian Slater 021 386 0206 / 021 386 0208 Motor Oil Athlone Adens Service Station Eden Ave 021 696 9941 Paper-Mondi Athlone Christel House School S A 38 Bamford Avenue Other Athlone Christel House School SA 38 Bamford Avenue 021 697 3037 Glass Athlone Express Waste Desre Road, Athlone, 7760 021 638 6593 Gerard Moen General Buy Back Athlone Express Waste 2 5 Desri Road Glass Athlone Garlandale Primary General Street Athlone 7764 021 696 8327 General Buy Back Athlone Industrial Scrap Southern Suburbs/'Mymona Road 021 448 5395 Glass Athlone LR Heydenreych 5 Bergzich Schoongezicht, Athlone, 7760 Collect-a-can Athlone Pen Beverages Athlone Industrial 021 684 4130 Paper and C/board Athlone Private 151 Lawrence Rd, Collect-a-can Athlone St. Raphaels School Lawrence Road 021 696 6718 Glass/ tins/ plastic Athlone Walkers Recycling 43 Brian Rd Greenhaven 083 508 1177 Glass Athlone Walker's Recycling 43 Brian Rd, Greenhaven, Athlone, 7760 021 638 1515 Eddie Walker General Buy Back Atlantis Berties Scrap Conaught Road All Materials Atlantis Grosvenor Hermeslaan 021 572 5487 All Materials -

Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant 6087 6087

PROVINCE OF WESTERN CAPE PROVINSIE WES-KAAP Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant 6087 6087 Friday, 21 November 2003 Vrydag, 21 November 2003 Registered at the Post Offıce as a Newspaper As ’n Nuusblad by die Poskantoor Geregistreer CONTENTS INHOUD (*Reprints are obtainable at Room 9-06, Provincial Building, 4 Dorp Street, (*Herdrukke is verkrygbaar by Kamer 9-06, Provinsiale-gebou, Dorp- Cape Town 8001.) straat 4, Kaapstad 8001.) No. Page No. Bladsy Proclamations Proklamasies 17 Western Cape Education Department: Closure of Public 17 Wes-Kaap Onderwysdepartement: Sluiting van Openbare School.................................................................................. 1494 Skool ................................................................................... 1494 18 Western Cape Education Department: Closure of Public 18 Wes-Kaap Onderwysdepartement: Sluiting van Openbare School.................................................................................. 1494 Skool ................................................................................... 1494 19 Western Cape Education Department: Closure of Public 19 Wes-Kaap Onderwysdepartement: Sluiting van Openbare School.................................................................................. 1494 Skool ................................................................................... 1494 20 Western Cape Education Department: Closure of Public 20 Wes-Kaap Onderwysdepartement: Sluiting van Openbare School................................................................................. -

Provincial Library Services

PROVINCIAL LIBRARY SERVICES EASTERN CAPE POST ADR : Private Bag X7486 : King William’s Town 5600 STREET ADR : 5 Eale Street : King William’s Town 5601 TELEPHONE : (043) 604-4015 / 604-4016 : (043) 604-4043 ( Nokwezi – Secretary ) FAX : (043) 644-2204 / 604-5684 CELL : 082 458 3708 E-MAIL : [email protected] : [email protected] ( Secretary ) CONTACT : MABANDLA, Nomzamo Ms FREE STATE POST ADR : Private Bag X20606 : Bloemfontein 9300 STREET ADR : Room 216 : 2nd Floor Business Partners Building : Cnr Henry & East Burger Streets : Bloemfontein 9301 TELEPHONE : (051) 410-4829 FAX : (051) 410-4829 CELL : 082 374 1740 E-MAIL : [email protected] : [email protected] ( Secretary ) CONTACT : SCHIMPER, Jacomien Ms GAUTENG POST ADR : Private Bag X33 : Johannesburg 2000 STREET ADR : Department of Sports, Arts, Culture and Recreation : NBS Building : 38 Rissik Street : Johannesburg 2001 TELEPHONE : (011) 355-2659 / 355-2500 ( Office ) FAX : (011) 355-2505 CELL : 083 507 8032 E-MAIL : [email protected] CONTACT : MEYER, Koekie Ms KWAZULU-NATAL POST ADR : Private Bag X9016 : Pietermaritzburg 3200 STREET ADR : 3rd Floor : KwaZulu Natal Provincial Library Service Building : 230 Prince Alfred Street : Pietermaritzburg 3201 TELEPHONE : (033) 341-3000 FAX : (033) 394-2237 / 341-3085 CELL : 083 307 9033 E-MAIL : [email protected] CONTACT : SLATER, Carol Ms 1 LIMPOPO POST ADR : Private Bag X9549 : Pietersburg 0700 STREET ADR : Department of Sport, Arts and Culture : Olympic Towers : Office 3-39 : C/O Biccard and Rabie Streets : Polokwane 0699 TELEPHONE : (015) 284 4090 FAX : 086 545 1294 / 1390 CELL : 083 256 8515 E-MAIL : [email protected] CONTACT : MASIA, Mbangiseni Chief MPUMALANGA POST ADR : P.O. -

Fish Hoek Looking Back

FISH HOEK LOOKING BACK by Joy Cobern Printed & Published by Fish Hoek Printing & Publishing cc P.O. Box 22165 Fish Hoek 7975 First Published 2003 1 PREFACE This book is not meant to be a full history of Fish Hoek but is intended for those living here or visiting who wish to know more about the area. I hope you enjoy it and end up knowing a little more about Fish Hoek. There are many people who have helped me and I would particularly like to thank Joe and Simone Frylinck, who really thought I could do it, Ethel may Gillard, for sharing her vast store of local information and fascinating reminiscences, Michael Walker and Clive Wakeford for encouragement and advice. To anyone else who thinks that they ought to be on that list, thank you too! 2 INDEX 1. Peers Cave……………………………………………………… 6 2. The First Explorations of the Fish Hoek Valley………………. 11 3. The Fish Hoek Farm……………………………………………15 4. The Early Days of the Village………………………………….. 23 5. Water and Electricity………………………………………….... 28 6. The Railway Comes to Fish Hoek……………………………... 33 7. Vischoek, Vishoek or Fish Hoek?................................................ 39 8. Beach Development…………………………………………….. 41 9. Beach Controversies……………………………………………. 48 10 Fish Hoek Main Road…………………………………………. 54 11. Early Businesses………………………………………………. 64 12. Local Government…………………………………………….. 70 13. The War Years…………………………………………………. 77 14. The Steps and Lanes…………………………………………... 81 15. Our Local Newspapers………………………………………... 85 16. The Battle of the Bottles………………………………………. 89 3 Fish Hoek 1922 Fish Hoek 1933 Fish Hoek 1947 4 1. Peers Cave Although the first plots in Fish Hoek were only sold in 1918 there have been people in the Fish Hoek Valley for many thousands of years, but it was only in the 1920's that the early history of the valley was uncovered. -

Libraries Open for Drop and Collect

Libraries open for drop and collect Library Physical Address Telephone Number E-mail Address Brackenfell Library Paradys Street, BRACKENFELL, 7560 021 - 400 3806 [email protected] Bellville Library Carel van Aswegen Street, BELLVILLE 7530 021 - 444 0300 [email protected] Colin Eglin, Sea Point Library Civic Centre, Cnr Three Anchor Bay & Main Rds, SEA POINT 8001 021 - 400 4184 [email protected] Crossroads Library Philippi Village, Cwangco Crescent, PHILIPPI 7781 021 - 444 2533 [email protected] Fisantekraal Library Cnr Dullah Omar & Peter Mokaba Street, FISANTEKRAAL 7500 021 - 444 9259 [email protected] Fish Hoek Library Central Circle, FISH HOEK 7975 021 - 400 7101/2 [email protected] Harare Library 42 Ncumo Street, Harare Square, Harare KHAYELITSHA 7530 021 - 444 0280 [email protected] Hout Bay Library Melkhout Crescent, HOUT BAY, 7800 021 - 791 7660 [email protected] Melton Rose Library Cnr Fynbos & Melbos Street, MELTON ROSE 7100 021 - 444 0980 [email protected] Parow Library Cnr McIntyre Street & 1st Avenue PAROW 7500 021 - 444 0940 [email protected] Rylands Library Balu Parker Driv e, GATESVILLE 7764 021 - 637 2220 [email protected] Strand Library Mills Street, STRAND 7140 021 - 444 3106 [email protected] Tokai Library Tokai Road, TOKAI, 7945 021 - 710 1480 [email protected] Town Centre Library Mitchell's Plain Town Centre, Symphony Walk,