Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mayor and Early Lollard Dissemination

University of Central Florida STARS HIM 1990-2015 2012 The mayor and early Lollard dissemination Angel Gomez University of Central Florida Part of the Medieval History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIM 1990-2015 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Gomez, Angel, "The mayor and early Lollard dissemination" (2012). HIM 1990-2015. 1774. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015/1774 THE MAYOR AND EARLY LOLLARD DISSEMINATION by ANGEL GOMEZ A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in History in the College of Arts and Humanities and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2012 Thesis Chair: Dr. Emily Graham Abstract During the fourteenth century in England there began a movement referred to as Lollardy. Throughout history, Lollardy has been viewed as a precursor to the Protestant Reformation. There has been a long ongoing debate among scholars trying to identify the extent of Lollard beliefs among the English. Attempting to identify who was a Lollard has often led historians to look at the trial records of those accused of being Lollards. One aspect overlooked in these studies is the role civic authorities, like the mayor of a town, played in the heresy trials of suspected Lollards. -

John Bale's <I>Kynge Johan</I> As English Nationalist Propaganda

Quidditas Volume 35 Article 10 2014 John Bale’s Kynge Johan as English Nationalist Propaganda G. D. George Prince George's County Public Schools, Prince George's Community College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation George, G. D. (2014) "John Bale’s Kynge Johan as English Nationalist Propaganda," Quidditas: Vol. 35 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol35/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Quidditas 35 (2014) 177 John Bale’s Kynge Johan as English Nationalist Propaganda G. D. George Prince George’s County Public Schools Prince George’s Community College John Bale is generally associated with the English Reformation rather than the Tudor government. It may be that Bale’s well-know protestant polemics tend to overshadow his place in Thomas Cromwell’s propaganda machine, and that Bale’s Kynge Johan is more a propaganda piece for the Tudor monarchy than it is just another of his Protestant dramas.. Introduction On 2 January, 1539, a “petie and nawghtely don enterlude,” that “put down the Pope and Saincte Thomas” was presented at Canterbury.1 Beyond the fact that a four hundred sixty-one year old play from Tudor England remains extant in any form, this particular “enterlude,” John Bale’s play Kynge Johan,2 remains of particular interest to scholars for some see Johan as meriting “a particular place in the history of the theatre. -

King John Take Place in the Thirteenth Century, Well Before Shakespeare’S Other English History Plays

Folger Shakespeare Library https://shakespeare.folger.edu/ Get even more from the Folger You can get your own copy of this text to keep. Purchase a full copy to get the text, plus explanatory notes, illustrations, and more. Buy a copy Contents From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library Front Textual Introduction Matter Synopsis Characters in the Play ACT 1 Scene 1 ACT 2 Scene 1 Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 3 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 1 ACT 4 Scene 2 Scene 3 Scene 1 Scene 2 Scene 3 ACT 5 Scene 4 Scene 5 Scene 6 Scene 7 From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library It is hard to imagine a world without Shakespeare. Since their composition four hundred years ago, Shakespeare’s plays and poems have traveled the globe, inviting those who see and read his works to make them their own. Readers of the New Folger Editions are part of this ongoing process of “taking up Shakespeare,” finding our own thoughts and feelings in language that strikes us as old or unusual and, for that very reason, new. We still struggle to keep up with a writer who could think a mile a minute, whose words paint pictures that shift like clouds. These expertly edited texts are presented to the public as a resource for study, artistic adaptation, and enjoyment. By making the classic texts of the New Folger Editions available in electronic form as The Folger Shakespeare (formerly Folger Digital Texts), we place a trusted resource in the hands of anyone who wants them. -

C.1530 Sarah Raskin

False Oaths The Silent Alliance between Church and Heretics in England, c.1400-c.1530 Sarah Raskin Submitted in partial fulFillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Sarah Raskin All rights reserved ABSTRACT False Oaths: The Silent Alliance between Church and Heretics in England, c. 1400-1530 Sarah Raskin This dissertation re-examines trials for heresy in England from 1382, which saw the First major action directed at the WyclifFite heresy in Oxford, and the early Reformation period, with an emphasis on abjurations, the oaths renouncing heretical beliefs that suspects were required to swear after their interrogations were concluded. It draws a direct link between the customs that developed around the ceremony of abjuration and the exceptionally low rate of execution for “relapsed” and “obstinate” heretics in England, compared to other major European anti-heresy campaigns of the period. Several cases are analyzed in which heretics who should have been executed, according to the letter and intention of canon law on the subject, were permitted to abjure, sometimes repeatedly. Other cases ended in execution despite intense efforts by the presiding bishop to obtain a similarly law-bending abjuration. All these cases are situated in the context of the constitutions governing heresy trials as well as a survey of the theology and cultural standing of oaths within both WyclifFism and the broader Late Medieval and Early Modern world. This dissertation traces how Lollard heretics gradually accepted the necessity of false abjuration as one of a number of measures to preserve their lives and their movement, and how early adopters using coded writing carefully persuaded their co-religionists of this necessity. -

Dawn of the Reformation Vol 1

THE DAWN OF THE REFORMATION BY HERBERT B. WORKMAN, MA. VOL. I THE AGE OF WYCLIF London: CHARLES H. KELLY 2, CASTLE ST., CITY RD.; AND 26, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1901 OCR and formatting by William H. Gross www.onthewing.org Nov 2016 Page breaks have been adjusted for readability (widow/orphan) PREFACE I HAVE entitled this little work The Dawn of the Reformation. My purpose is to trace the various influences and forces both within and without the Church, which produced the great revolution of the sixteenth century. At what hour" dawn" begins is always a matter of dispute, and depends largely on local circumstances. But one thing is certain. A new day has begun long before the average worker has commenced his toil. So with the Reformation. The study of its causes cannot commence with Erasmus or Savonarola; its methods and results were to some extent settled for it in the century before Luther or Cranmer. My narrow limits have compelled me to omit many things of interest, and to compress into a few lines others which demanded as many pages. viii PREFACE I have constantly realised that to write a small history is more difficult than to write one of larger margins. In what I have included, as well as in what I have omitted, the understanding of the Reformation and its causes has alone had weight. If it be objected that I have given a disproportionate space to Wyclif, or made him bulk larger than he did in his own day, I must plead that his life has scarcely received the attention it deserves. -

Understanding Shakespeare's King John and Magna Carta in the Light

Bilgi [2018 Yaz], 20 [1]: 241-259 Understanding Shakespeare’s King John and 1 Magna Carta in the Light of New Historicism Kenan Yerli2 Abstract: Being one of the history plays of William Shakespeare, The Life and Death of King John tells the life and important polit- ical matters of King John (1166-1216). In this play, Shakespeare basically relates the political issues of King John to Queen Eliza- beth I. Political matters such as the threat of invasion by a foreign country, divine right of kings; papal excommunication and legit- imacy discussions constitute the main themes of the play. How- ever, Shakespeare does not mention a word of Magna Carta throughout the play. In this regard, it is critical to figure out and explain the reason why Shakespeare did not mention Magna Car- ta in his The Life and Death of King John, owing to the im- portance of Magna Carta in the history of England. In this respect, the analysis of The Life and Death of King John in the light of new historicism helps us to understand both how Shakespeare re- lated the periods of Queen Elizabeth and King John; and the rea- son why Shakespeare did not mention Magna Carta in his play. Keywords: Shakespeare, New Historicism, Magna Carta, Eliza- bethan Drama. 1. This article has been derived from the doctoral dissertation entitled Political Propaganda in Shakespeare’s History Plays. 2. Sakarya University, School of Foreign Languages. 242 ▪ Kenan Yerli Being one of the most important playwrights of all times, William Shakespeare wrote and staged great number of plays about English history. -

King John Article (Cathleen Sheehan)

The Historical King John By Cathleen Sheehan, Dramaturg Today, King John is a little-known historical figure. If you are a student of history, you might connect him to the Magna Carta; if you are a student of romance literature (or Disney films), you might recognize him as the nemesis of Robin Hood. For Shakespeare’s contemporaries, however, King John was a compelling figure—a complicated king whose reign resonated with the anxieties of the day. In King John, Shakespeare addresses the fears of England as a land of civil disputes, subject to foreign invasion and Papal interference. The most pressing and controversial issues in the play are questions of succession and legitimacy. Shakespeare used several sources for the story—relying predictably on Holinshed, the official Tudor chronicler, as well as John Foxe’s Actes and Monuments. As always, Shakespeare’s adaptation of historical facts—or what were taken to be facts—reveals his thematic and dramatic intentions. The play opens in roughly 1199 with the French making gestures of aggression toward King John. France disputes John’s right to be king—backing instead his nephew Arthur, the son of John’s older brother Geoffrey. Presumably, King Philip of France likes the thought of a French-raised, very young king in England—a king who might be easy to influence and more favorably inclined toward France. And Arthur’s claim to the throne is not so easily dismissed, as John’s mother even admits. Arthur’s claim pits inheritance by primogeniture against inheritance by will—a pertinent tension in Shakespeare’s day. -

John Foxe's 'Acts and Monuments' and the Lollard Legacy in the Long English Reformation

Durham E-Theses John Foxe's 'Acts and Monuments' and the Lollard Legacy in the Long English Reformation ROYAL, SUSAN,ANN How to cite: ROYAL, SUSAN,ANN (2014) John Foxe's 'Acts and Monuments' and the Lollard Legacy in the Long English Reformation, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10624/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 John Foxe's Acts and Monuments and the Lollard Legacy in the Long English Reformation Susan Royal A Thesis Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Durham University Department of Theology and Religion 2013 Abstract This thesis addresses a perennial historiographical question of the English Ref- ormation: to what extent, if any, the late medieval dissenters known as lollards influenced the Protestant Reformation in England. To answer this question, this thesis looks at the appropriation of the lollards by evangelicals such as William Tyndale, John Bale, and especially John Foxe, and through them by their seven- teenth century successors. -

Review Essay

Early Theatre 16.1 (2013), 151–75 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.12745/et.16.1.9 Review Essay Kent Cartwright Defining Tudor Drama The gods are smiling upon the field of Tudor literature — perhaps to para- doxical effect, as we shall later see. In 2009 Oxford University Press published Mike Pincombe and Cathy Shrank’s magnificent (and award-winning) col- lection of multi-authored essays The Oxford Handbook of Tudor Literature.1 For drama specialists, Oxford has now followed it with Thomas Betteridge and Greg Walker’s The Oxford Handbook of Tudor Drama.2 This fresh atten- tion to Tudor literature has surely received encouragement from scholarly interest in political history and in religious change during the sixteenth century in England, as illustrated in drama studies by the transformational influence of, for example, Paul Whitfield White’s 1993 Theatre and Reforma- tion: Protestantism, Patronage and Playing in Tudor England. The important Records of Early English Drama project, now almost four decades old, has bolstered such interests.3 More recently, Tudor literature has figured in the ongoing reconsideration of a reigning theory of literary periodization that segmented off what was ‘medieval’ from what was ‘Renaissance’; that recon- sideration, well under way, now tracks the long reach of medieval values and worldviews into the 1530s and beyond. Tudor literary studies has received impetus, too, from the tireless efforts of a number of eminent scholars. Greg Walker, the co-editor of the Handbook, for instance, has authored a series of books on Tudor drama (and most recently Tudor literature) that display a fine-grained, locally attuned, paradigm-setting political analysis at a level never before achieved. -

The New Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare Edited by Margreta De Grazia and Stanley Wells Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88632-1 - The New Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare Edited by Margreta De Grazia and Stanley Wells Index More information INDEX Note: Page numbers for illustrations are given in italics. Works by Shakespeare appear under title; works by others under author’s name. 4D art: La Tempête 296 , 297 language 83–4 , 86 , 202 , 203 , 208 performance 52 , 333 actor-managers 287 sexuality and gender 221 actors apprentices 45–6 actions and feelings 194–5 Arabic performances 297–8 globalization 287–91 Archer, William 236 performance 233–8 , 248–9 , 287–8 Arden, Mary ( later Shakespeare) xiv , in Shakespeare’s London 45–9 , 61 4 , 5 see also boy actors Arden, Robert 4 , 5 Adams, W. E. 68 ‘Arden Shakespeare’ 69 , 73 , 83 , 255 , 292 , Addison, Joseph 80–1 326 Adelman, Janet Ariosto, Ludovico: Orlando Furioso 92 Hamlet to the Tempest 338 Aristotle 88 , 122 , 128 , 138 Suffocating Mothers: Fantasies of Armin, Robert 46 , 98 Maternal Origin in Shakespeare’s art 339 Plays 338 As You Like It xv , 62 , 114–15 Aesop: Fables 19 categorization 171 Afghanistan 289–90 , 294 characters 46 Age of Kings, An (BBC mini-series) 313 language 17 Akala 280–1 plot devices 109 , 173 Al-Bassam, Sulayman: Richard III – An Arab sexuality and gender 218 , 219 , 223–4 Tragedy 297–8 sources 23 Alexander, Shelton 280 theatre 51 , 52 All is True see Henry VIII Ascham, Roger: The Scholemaster 18 , 20 , Allen, A. J. B. 327 22–3 Allot, Robert: England’s Parnassus 91 Aubrey, John 8 All’s Well That Ends Well xvi , 62 , 84 , audiences 116–17 , 122 , 199 , 213 , 219 audience agency 316–17 Almereyda, Michael: Hamlet 318 , 319–21 , early modern popular culture 271–3 , 274 320 media history 315–17 Amyot, Jacques 20 authors and authorship 1 , 32–4 , 61–2 , 97 , Andrews, John F.: William Shakespeare: His 291–5 , 308 World, His Work, His Infl uence 328 Autran, Paulo 290–1 anti-Stratfordianism 273 Antony and Cleopatra xvi , 62 , 162–3 Bacon, Francis 128 actors 46 Bakhtin, Michaïl 275 characters 163 , 274 Baldwin, T. -

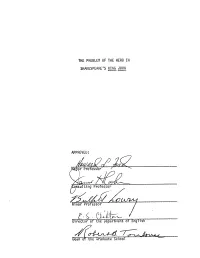

THE PROBLEM of the HERO in SHAKESPEARE's KING JOHN APPROVED: R Professor Suiting Professor Minor Professor Partment of English

THE PROBLEM OF THE HERO IN SHAKESPEARE'S KING JOHN APPROVED: r Professor / suiting Professor Minor Professor l-Q [Ifrector of partment of English Dean or the Graduate School THE PROBLEM OF THE HERO IN SHAKESPEARE'S KING JOHN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Wilbert Harold Ratledge, Jr., B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1970 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. THE MILIEU OF KING JOHN 7 III. TUDOR HISTORIOGRAPHY 12 IV. THE ENGLISH CHRONICLE PLAY 22 V. THE SOURCES OF KING JOHN 39 VI. JOHN AS HERO 54 VII. FAULCONBRIDGE AS HERO 67 VIII. ENGLAND AS HERO 82 IX. WHO IS THE VILLAIN? 102 X. CONCLUSION BIBLIOGRAPHY 118 in CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION During the last twenty-five years Shakespeare scholars have puolished at least five major works which deal extensively with Shakespeare's history plays. In addition, many critical articles concerning various aspects of the histories have been published. Some of this new material reinforces traditional interpretations of the history plays; some offers new avenues of approach and differs radically in its consideration of various elements in these dramas. King John is probably the most controversial of Shakespeare's history plays. Indeed, almost everything touching the play is in dis- pute. Anyone attempting to investigate this drama must be wary of losing his way among the labyrinths of critical argument. Critical opinion is amazingly divided even over the worth of King John. Hardin Craig calls it "a great historical play,"^ and John Masefield finds it to be "a truly noble play . -

Dramatic Form in the Early Modern English History Play

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Dramatic Form in the Early Modern English History Play A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of English School of Arts and Sciences Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Shaun Stiemsma Washington, DC 2017 Dramatic Form in the Early Modern English History Play Shaun Stiemsma, Ph.D. Director: Michael Mack, Ph.D. The early modern history play has been assumed to exist as an independent genre at least since Shakespeare’s first folio divided his plays into comedies, tragedies, and histories. However, history has never—neither during the period nor in literary criticism since—been satisfactorily defined as a distinct dramatic genre. I argue that this lack of definition obtains because early modern playwrights did not deliberately create a new genre. Instead, playwrights using history as a basis for drama recognized aspects of established genres in historical source material and incorporated them into plays about history. Thus, this study considers the ways in which playwrights dramatizing history use, manipulate, and invert the structures and conventions of the more clearly defined genres of morality, comedy, and tragedy. Each chapter examines examples to discover generic patterns present in historical plays and to assess the ways historical materials resist the conceptions of time suggested by established dramatic genres. John Bale’s King Johan and the anonymous Woodstock both use a morality structure on a loosely contrived history but cannot force history to conform to the apocalyptic resolution the genre demands.