Understanding Shakespeare's King John and Magna Carta in the Light

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three Minor Revisions

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2001 The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions John Donald Hosler Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Hosler, John Donald, "The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions" (2001). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 21277. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/21277 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions by John Donald Hosler A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Major Professor: Kenneth G. Madison Iowa State University Ames~Iowa 2001 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of John Donald Hosler has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy 111 The liberal arts had not disappeared, but the honours which ought to attend them were withheld Gerald ofWales, Topograhpia Cambria! (c.1187) IV TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION 1 Overview: the Reign of Henry II of England 1 Henry's Conflict with Thomas Becket CHAPTER TWO. -

King Henry II & Thomas Becket

Thomas a Becket and King Henry II of England A famous example of conflict between a king and the Medieval Christian Church occurred between King Henry II of England and Thomas a Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury. King Henry and Becket were onetime friends. Becket had been working as a clerk for the previous Archbishop of Canterbury. This was an important position because the Archbishop of Canterbury was the head of the Christian Church in England. Thomas Becket was such an efficient and dedicated worker he was eventually named Lord Chancellor. The Lord Chancellor was a clerk who worked directly for the king. In 1162, Theobald of Bec, the Archbishop of Canterbury, died. King Henry saw this as an opportunity to increase his control over the Christian Church in England. He decided to appoint Thomas Becket to be the new Archbishop of Canterbury reasoning that, because of their relationship, Becket would support Henry’s policies. He was wrong. Instead, Becket worked vigorously to protect the interests of the Church even when that meant disagreeing with King Henry. Henry and Becket argued over tax policy and control of church land but the biggest conflict was over legal rights of the clergy. Becket claimed that if a church official was accused of a crime, only the church itself had the ability to put the person on trial. King Henry said that his courts had jurisdiction over anyone accused of a crime in England. This conflict became increasingly heated until Henry forced many of the English Bishops and Archbishops to agree to the Constitution of Clarendon. -

John Bale's <I>Kynge Johan</I> As English Nationalist Propaganda

Quidditas Volume 35 Article 10 2014 John Bale’s Kynge Johan as English Nationalist Propaganda G. D. George Prince George's County Public Schools, Prince George's Community College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation George, G. D. (2014) "John Bale’s Kynge Johan as English Nationalist Propaganda," Quidditas: Vol. 35 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol35/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Quidditas 35 (2014) 177 John Bale’s Kynge Johan as English Nationalist Propaganda G. D. George Prince George’s County Public Schools Prince George’s Community College John Bale is generally associated with the English Reformation rather than the Tudor government. It may be that Bale’s well-know protestant polemics tend to overshadow his place in Thomas Cromwell’s propaganda machine, and that Bale’s Kynge Johan is more a propaganda piece for the Tudor monarchy than it is just another of his Protestant dramas.. Introduction On 2 January, 1539, a “petie and nawghtely don enterlude,” that “put down the Pope and Saincte Thomas” was presented at Canterbury.1 Beyond the fact that a four hundred sixty-one year old play from Tudor England remains extant in any form, this particular “enterlude,” John Bale’s play Kynge Johan,2 remains of particular interest to scholars for some see Johan as meriting “a particular place in the history of the theatre. -

Eleanor of Aquitaine and 12Th Century Anglo-Norman Literary Milieu

THE QUEEN OF TROUBADOURS GOES TO ENGLAND: ELEANOR OF AQUITAINE AND 12TH CENTURY ANGLO-NORMAN LITERARY MILIEU EUGENIO M. OLIVARES MERINO Universidad de Jaén The purpose of the present paper is to cast some light on the role played by Eleanor of Aquitaine in the development of Anglo-Norman literature at the time when she was Queen of England (1155-1204). Although her importance in the growth of courtly love literature in France has been sufficiently stated, little attention has been paid to her patronising activities in England. My contribution provides a new portrait of the Queen of Troubadours, also as a promoter of Anglo-Norman literature: many were the authors, both French and English, who might have written under her royal patronage during the second half of the 12th century. Starting with Rita Lejeune’s seminal work (1954) on the Queen’s literary role, I have gathered scattered information from different sources: approaches to Anglo-Norman literature, Eleanor’s biographies and studies in Arthurian Romance. Nevertheless, mine is not a mere systematization of available data, for both in the light of new discoveries and by contrasting existing information, I have enlarged agreed conclusions and proposed new topics for research and discussion. The year 2004 marked the 800th anniversary of Eleanor of Aquitaine’s death. An exhibition was held at the Abbey of Fontevraud (France), and a long list of books has been published (or re-edited) about the most famous queen of the Middle Ages during these last six years. 1 Starting with R. Lejeune’s seminal work (1954) on 1. -

Killing Shakespeare's Children: the Cases of Richard III and King John Joseph Campana

Campana, J. (2007). Killing Shakespeare’s Children: The Cases of Richard III and King John. Shakespeare, 3(1), 18–39. doi:10.1080/17450910701252271 Killing Shakespeare's Children: The Cases of Richard III and King John Joseph Campana This essay explores a series of affective, sexual and temporal disturbances that Shakespeare's child characters create on the early modern stage and that lead these characters often to their deaths. It does so by turning to the murdered princes of Richard III and the ultimately extinguished boy-king Arthur of King John. A pervasive sentimentality about childhood shapes the way audiences and critics have responded to Shakespeare's children by rendering invisible complex and discomfiting erotic and emotional investments in childhood innocence. While Richard III subjects such sentimentality to its analytic gaze, King John explores extreme modes of affect and sexuality associated with childhood. For all of the pragmatic political reasons to kill Arthur, he is much more than an inconvenient dynastic obstacle. Arthur functions as the central node of networks of seduction, the catalyst of morbid displays of affect, and the signifier of future promise as threateningly mutable. King John and Richard III typify Shakespeare's larger dramatic interrogation of emergent notions of childhood and of contradictory notions of temporality, an interrogation conducted by the staging of uncanny, precocious, and ill-fated child roles. Keywords: Children; childhood; seduction; sexuality; affect; temporality; Richard III; King John If it is fair to say that Shakespeare included in his plays more child roles than did his contemporaries (Ann Blake counts thirty; Mark Heberle counts thirty-nine), it is also fair to say Shakespeare provided a wide range of parts for those children: from pivotal roles in royal succession to trace presences as enigmatic markers of symbolic equations never perhaps to be solved. -

King John Take Place in the Thirteenth Century, Well Before Shakespeare’S Other English History Plays

Folger Shakespeare Library https://shakespeare.folger.edu/ Get even more from the Folger You can get your own copy of this text to keep. Purchase a full copy to get the text, plus explanatory notes, illustrations, and more. Buy a copy Contents From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library Front Textual Introduction Matter Synopsis Characters in the Play ACT 1 Scene 1 ACT 2 Scene 1 Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 3 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 1 ACT 4 Scene 2 Scene 3 Scene 1 Scene 2 Scene 3 ACT 5 Scene 4 Scene 5 Scene 6 Scene 7 From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library It is hard to imagine a world without Shakespeare. Since their composition four hundred years ago, Shakespeare’s plays and poems have traveled the globe, inviting those who see and read his works to make them their own. Readers of the New Folger Editions are part of this ongoing process of “taking up Shakespeare,” finding our own thoughts and feelings in language that strikes us as old or unusual and, for that very reason, new. We still struggle to keep up with a writer who could think a mile a minute, whose words paint pictures that shift like clouds. These expertly edited texts are presented to the public as a resource for study, artistic adaptation, and enjoyment. By making the classic texts of the New Folger Editions available in electronic form as The Folger Shakespeare (formerly Folger Digital Texts), we place a trusted resource in the hands of anyone who wants them. -

Gesture and Movement in Silent Shakespeare Films

Gesticulated Shakespeare: Gesture and Movement in Silent Shakespeare Films Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Rebecca Collins, B.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Alan Woods, Advisor Janet Parrott Copyright by Jennifer Rebecca Collins 2011 Abstract The purpose of this study is to dissect the gesticulation used in the films made during the silent era that were adaptations of William Shakespeare's plays. In particular, this study investigates the use of nineteenth and twentieth century established gesture in the Shakespearean film adaptations from 1899-1922. The gestures described and illustrated by published gesture manuals are juxtaposed with at least one leading actor from each film. The research involves films from the experimental phase (1899-1907), the transitional phase (1908-1913), and the feature film phase (1912-1922). Specifically, the films are: King John (1899), Le Duel d'Hamlet (1900), La Diable et la Statue (1901), Duel Scene from Macbeth (1905), The Taming of the Shrew (1908), The Tempest (1908), A Midsummer Night's Dream (1909), Il Mercante di Venezia (1910), Re Lear (1910), Romeo Turns Bandit (1910), Twelfth Night (1910), A Winter's Tale (1910), Desdemona (1911), Richard III (1911), The Life and Death of King Richard III (1912), Romeo e Giulietta (1912), Cymbeline (1913), Hamlet (1913), King Lear (1916), Hamlet: Drama of Vengeance (1920), and Othello (1922). The gestures used by actors in the films are compared with Gilbert Austin's Chironomia or A Treatise on Rhetorical Delivery (1806), Henry Siddons' Practical Illustrations of Rhetorical Gesture and Action; Adapted to The English Drama: From a Work on the Subject by M. -

Elizabeth I and Irish Rule: Causations For

ELIZABETH I AND IRISH RULE: CAUSATIONS FOR CONTINUED SETTLEMENT ON ENGLAND’S FIRST COLONY: 1558 - 1603 By KATIE ELIZABETH SKELTON Bachelor of Arts in History Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2009 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 2012 ELIZABETH I AND IRISH RULE: CAUSATIONS FOR CONTINUED SETTLEMENT ON ENGLAND’S FIRST COLONY: 1558 - 1603 Thesis Approved: Dr. Jason Lavery Thesis Adviser Dr. Kristen Burkholder Dr. L.G. Moses Dr. Sheryl A. Tucker Dean of the Graduate College ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 1 II. ENGLISH RULE OF IRELAND ...................................................... 17 III. ENGLAND’S ECONOMIC RELATIONSHIP WITH IRELAND ...................... 35 IV. ENGLISH ETHNIC BIAS AGAINST THE IRISH ................................... 45 V. ENGLISH FOREIGN POLICY & IRELAND ......................................... 63 VI. CONCLUSION ...................................................................... 90 BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................................................ 94 iii LIST OF MAPS Map Page The Island of Ireland, 1450 ......................................................... 22 Plantations in Ireland, 1550 – 1610................................................ 72 Europe, 1648 ......................................................................... 75 iv LIST OF TABLES Table Page -

Converted by Filemerlin

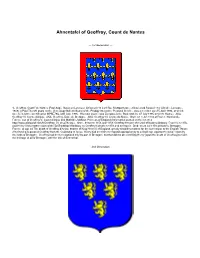

Ahnentafel of Geoffroy, Count de Nantes --- 1st Generation --- 1. Geoffroy, Count1 de Nantes (Paul Augé, Nouveau Larousse Universel (13 à 21 Rue Montparnasse et Boulevard Raspail 114: Librairie Larousse, 1948).) (Paul Theroff, posts on the Genealogy Bulletin Board of the Prodigy Interactive Personal Service, was a member as of 5 April 1994, at which time he held the identification MPSE79A, until July, 1996. His main source was Europaseische Stammtafeln, 07 July 1995 at 00:30 Hours.). AKA: Geoffroy VI, Comte d'Anjou. AKA: Geoffroy, Duke de Bretagne. AKA: Geoffroy VI, Comte du Maine. Born: on 3 Jun 1134 at Rouen, Normandie, France, son of Geoffroy V, Count d'Anjou and Mathilde=Mahaut, Princess of England (Information posted on the Internet, http://www.wikiwand.com/fr/Geoffroy_VI_d%27Anjou.). Note - between 1156 and 1158: Geoffroy became the Lord of Nantes (Brittany, France) in 1156, and Henry II his brother claimed the overlordship of Brittany on Geoffrey's death in 1158 and overran it. Died: on 26 Jul 1158 at Nantes, Bretagne, France, at age 24 The death of Geoffroy d'Anjou, brother of King Henry II of England, greatly simplifies matters for the succession to the English Throne. After having separated Geoffroy from the Countship of Anjou, Henry had sent him to respond appropriatetly to a challenge against the ducal crown by the lords of Bretagne. Geoffroy had been recognized only by part of Bretagne, but that did not prevent King Henry [upon the death of Geoffroy] to claim the heritage of all of Bretagne, with the title of Seneschal. --- 2nd Generation --- Coat of Arm associated with Geoffroy V, Comte d'Anjou. -

Inauguration and Images of Kingship in England, France and the Empire C.1050-C.1250

Christus Regnat: Inauguration and Images of Kingship in England, France and the Empire c.1050-c.1250 Johanna Mary Olivia Dale Submitted for examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of History November 2013 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract This thesis challenges the traditional paradigm, which assumes that the period c.1050-c.1250 saw a move away from the ‘biblical’ or ‘liturgical’ kingship of the early Middle Ages towards ‘administrative’ or ‘law-centred’ interpretations of rulership. By taking an interdisciplinary and transnational approach, and by bringing together types of source material that have traditionally been studied in isolation, a continued flourishing of Christ-centred kingship in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries is exposed. In demonstrating that Christological understandings of royal power were not incompatible with bureaucratic development, the shared liturgically inspired vocabulary deployed by monarchs in the three realms is made manifest. The practice of monarchical inauguration forms the focal point of the thesis, which is structured around three different types of source material: liturgical texts, narrative accounts and charters. Rather than attempting to trace the development of this ritual, an approach that has been taken many times before, this thesis is concerned with how royal inauguration was understood by contemporaries. Key insights include the importance of considering queens in the construction of images of royalty, the continued significance of unction despite papal attempts to lower the status of royal anointing, and the depth of symbolism inherent in the act of coronation, which enables a reinterpretation of this part of the inauguration rite. -

Heineman Royal Ancestors Medieval Europe

HERALDRYand BIOGRAPHIES of the HEINEMAN ROYAL ANCESTORS of MEDIEVAL EUROPE HERALDRY and BIOGRAPHIES of the HEINEMAN ROYAL ANCESTORS of MEDIEVAL EUROPE INTRODUCTION After producing numerous editions and revisions of the Another way in which the royal house of a given country familiy genealogy report and subsequent support may change is when a foreign prince is invited to fill a documents the lineage to numerous royal ancestors of vacant throne or a next-of-kin from a foreign house Europe although evident to me as the author was not clear succeeds. This occurred with the death of childless Queen to the readers. The family journal format used in the Anne of the House of Stuart: she was succeeded by a reports, while comprehensive and the most popular form prince of the House of Hanover who was her nearest for publishing genealogy can be confusing to individuals Protestant relative. wishing to trace a direct ancestral line of descent. Not everyone wants a report encumbered with the names of Unlike all Europeans, most of the world's Royal Families every child born to the most distant of family lines. do not really have family names and those that have adopted them rarely use them. They are referred to A Royal House or Dynasty is a sort of family name used instead by their titles, often related to an area ruled or by royalty. It generally represents the members of a family once ruled by that family. The name of a Royal House is in various senior and junior or cadet branches, who are not a surname; it just a convenient way of dynastic loosely related but not necessarily of the same immediate identification of individuals. -

King John Article (Cathleen Sheehan)

The Historical King John By Cathleen Sheehan, Dramaturg Today, King John is a little-known historical figure. If you are a student of history, you might connect him to the Magna Carta; if you are a student of romance literature (or Disney films), you might recognize him as the nemesis of Robin Hood. For Shakespeare’s contemporaries, however, King John was a compelling figure—a complicated king whose reign resonated with the anxieties of the day. In King John, Shakespeare addresses the fears of England as a land of civil disputes, subject to foreign invasion and Papal interference. The most pressing and controversial issues in the play are questions of succession and legitimacy. Shakespeare used several sources for the story—relying predictably on Holinshed, the official Tudor chronicler, as well as John Foxe’s Actes and Monuments. As always, Shakespeare’s adaptation of historical facts—or what were taken to be facts—reveals his thematic and dramatic intentions. The play opens in roughly 1199 with the French making gestures of aggression toward King John. France disputes John’s right to be king—backing instead his nephew Arthur, the son of John’s older brother Geoffrey. Presumably, King Philip of France likes the thought of a French-raised, very young king in England—a king who might be easy to influence and more favorably inclined toward France. And Arthur’s claim to the throne is not so easily dismissed, as John’s mother even admits. Arthur’s claim pits inheritance by primogeniture against inheritance by will—a pertinent tension in Shakespeare’s day.