Dawn of the Reformation Vol 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mayor and Early Lollard Dissemination

University of Central Florida STARS HIM 1990-2015 2012 The mayor and early Lollard dissemination Angel Gomez University of Central Florida Part of the Medieval History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIM 1990-2015 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Gomez, Angel, "The mayor and early Lollard dissemination" (2012). HIM 1990-2015. 1774. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015/1774 THE MAYOR AND EARLY LOLLARD DISSEMINATION by ANGEL GOMEZ A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in History in the College of Arts and Humanities and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2012 Thesis Chair: Dr. Emily Graham Abstract During the fourteenth century in England there began a movement referred to as Lollardy. Throughout history, Lollardy has been viewed as a precursor to the Protestant Reformation. There has been a long ongoing debate among scholars trying to identify the extent of Lollard beliefs among the English. Attempting to identify who was a Lollard has often led historians to look at the trial records of those accused of being Lollards. One aspect overlooked in these studies is the role civic authorities, like the mayor of a town, played in the heresy trials of suspected Lollards. -

Religious Forms and Institutions in Piers Plowman

This essay appeared in The Cambridge Companion to Piers Plowman, edited by Andrew Cole and Andy Galloway (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 97-116 Religious Forms and Institutions in Piers Plowman James Simpson KEY WORDS: William Langland, Piers Plowman, selfhood and institutions; late medieval religious institutions ABSTRACT Which comes first: institutions or selves? Liberal democracies operate as if selves preceded institutions. By and large, pre-Reformation culture places the institution before the self. The self, and particularly the conscience as the source of deepest ethical and spiritual counsel, is intimately shaped, by the institution of the Church. This shaping is both ethical and spiritual; by no means least, it ensures the soul’s salvation, though administering the sacraments especially of baptism, penance, and the Eucharist. The conscience is not a lonely entity in such an institutional culture. It is, rather, the portable voice of accumulated, communal history and wisdom: it is, as the word itself suggests, a ‘con-scientia’, a ‘knowing with’. These tensions generate the extraordinary and conflicted account of self and institution in Langland’s Piers Plowman. 1 Religious Forms and Institutions in Piers Plowman Which comes first: institutions or selves? Liberal democracies operate as if selves preceded institutions, since electors choose their institutional representatives, who themselves vote to shape institutions. Liberal ideology, indeed, traces its genealogy back to heroic moments of the lonely, fully-formed conscience standing up against the might of institutions; those heroes (Luther is the most obvious example) are lionized precisely because they are said to have established the grounds of choice: every individual will be able to choose, in freedom, his or her institutional affiliation for him or herself. -

Style: Figuring Subjectivity in 'Piers Plowman C' and 'The Parson's Tale' and 'Retraction': Authorial Insertion and Identity Poetics 04/05/2006 09:03 AM

Style: Figuring subjectivity in 'Piers Plowman C' and 'The Parson's Tale' and 'Retraction': authorial insertion and identity poetics 04/05/2006 09:03 AM FindArticles > Style > Fall, 1997 > Article > Print friendly Figuring subjectivity in 'Piers Plowman C' and 'The Parson's Tale' and 'Retraction': authorial insertion and identity poetics Daniel F. Pigg For some time, scholars and readers of Chaucer have pondered his knowledge about one of the major poets of his day: William Langland. Readers may typically find statements in scholarly discourse such as "We can now scarcely avoid considering the probability of Chaucer's having actually seen a copy of Piers Plowman in the interval between its first publication (c. 1370) and the beginnings of the Tales at least ten years later" (Bennett 321). Given internal evidence in the fifth passus of the C text - if we are willing to accept any connection between Langland's "autobiographical" confession/apologia and the writer - and documentary evidence of the historical Chaucer, we must assume that each poet was in London for at least a short time. Hypotheses about Chaucer's reading have always been at the forefront of scholarly debate. No one, however, has been about to demonstrate absolutely that Chaucer had knowledge of Piers Plowman. In her closing remarks at the 1994 New Chaucer Society meeting in Dublin, Ireland, Anne Middleton challenged those present to "trouble Chaucer's silences." The present attempt to "trouble the silence" relates to the growth and development of major poetic projects: the C text of Piers Plowman (likely written in the 1380s) and the "final" shape of the Canterbury Tales. -

C.1530 Sarah Raskin

False Oaths The Silent Alliance between Church and Heretics in England, c.1400-c.1530 Sarah Raskin Submitted in partial fulFillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Sarah Raskin All rights reserved ABSTRACT False Oaths: The Silent Alliance between Church and Heretics in England, c. 1400-1530 Sarah Raskin This dissertation re-examines trials for heresy in England from 1382, which saw the First major action directed at the WyclifFite heresy in Oxford, and the early Reformation period, with an emphasis on abjurations, the oaths renouncing heretical beliefs that suspects were required to swear after their interrogations were concluded. It draws a direct link between the customs that developed around the ceremony of abjuration and the exceptionally low rate of execution for “relapsed” and “obstinate” heretics in England, compared to other major European anti-heresy campaigns of the period. Several cases are analyzed in which heretics who should have been executed, according to the letter and intention of canon law on the subject, were permitted to abjure, sometimes repeatedly. Other cases ended in execution despite intense efforts by the presiding bishop to obtain a similarly law-bending abjuration. All these cases are situated in the context of the constitutions governing heresy trials as well as a survey of the theology and cultural standing of oaths within both WyclifFism and the broader Late Medieval and Early Modern world. This dissertation traces how Lollard heretics gradually accepted the necessity of false abjuration as one of a number of measures to preserve their lives and their movement, and how early adopters using coded writing carefully persuaded their co-religionists of this necessity. -

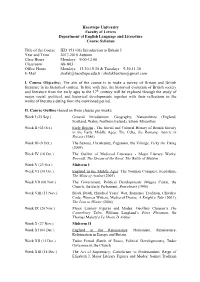

Hacettepe University Faculty of Letters Department of English Language and Literature Course Syllabus

Hacettepe University Faculty of Letters Department of English Language and Literature Course Syllabus Title of the Course IED 151 (03) Introduction to Britain I Year and Term 2017-2018 Autumn Class Hours Mondays – 9.00-12.00 Classroom B8-B03 Office Hours Mondays – 13.30-15.30 & Tuesdays – 9.30-11.30 E-Mail [email protected] / [email protected] I. Course Objective: The aim of the course is to make a survey of Britain and British literature in its historical context. In line with this, the historical evolution of British society and literature from the early ages to the 17th century will be explored through the study of major social, political, and historical developments together with their reflections in the works of literature dating from the mentioned period. II. Course Outline (based on three classes per week): Week I (25 Sep.) General Introduction: Geography, Nationalities (England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland), Ethnic Minorities Week II (02 Oct.) Early Britain - The Social and Cultural History of British Society in the Early Middle Ages: The Celts, the Romans, Asterix in Britain (1986) Week III (9 Oct.) The Saxons, Christianity, Paganism, the Vikings, Vicky the Viking (2009) Week IV (16 Oct.) The Outline of Medieval Literature - Major Literary Works: Beowulf, The Dream of the Rood, The Battle of Maldon Week V (23 Oct.) Midterm I Week VI (30 Oct.) England in the Middle Ages: The Norman Conquest, Feudalism, The Mists of Avalon (2001) Week VII (06 Nov.) The Government, Political Developments (Magna Carta), the Church, -

The Life of the Poet

The Life of the Poet No one knows who wrote Piers Plowman, and if someone named William Langland did so, no one knows anything certain about him.1 The only evi- dence for that name’s association with the poem comes from three notes that readers penned into the pastedowns (the inside covers) of two me- dieval manuscripts. These short, spontaneous glosses, read together with the few references in the poem to the narrator as “Will,” provide the only grounds for attributing the poem to a named author. The first note, dated ca. 1400, in a manuscript ofPiers Plowman from Gloucestershire but discovered in Ireland (Dublin, Trinity College, MS D.4.1), reads: Memorandum, quod Stacy de Rokayle, pater Willielmi de Langlond, qui Stacius fuit generosus et morabatur in Schiptone under Whic- wode, Tenens domini le Spenser in comitatu Oxon., qui praedic- tus Willielmus fecit librum qui vocatur Perys Ploughman. (Adams, Rokele Family 19) It was Stacy de Rokayle who was William de Langlond’s father; this Stacy was of gentle birth and lived in Shipton-under-Wychwood in Oxfordshire, holding land from Lord le Spenser; the aforesaid Wil- liam wrote the book called Piers Plowman. (Kane, ODNB 488)2 The other notes are found in a manuscript now in the Huntington Library, Hm 128. One, penned by Tudor historian John Bale, offers information similar to that of the Dublin manuscript but gives a different first name for the poet: 2 • An Introduction to Piers Plowman Robertus Langlande natus in comitatu Salopie in villa Mortymers Clybery in the claylande, within .viij. -

Langland, William (C. 1325–C. 1390), Poet | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Langland, William (c. 1325–c. 1390) George Kane https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/16021 Published in print: 23 September 2004 Published online: 23 September 2004 Langland, William (c. 1325–c. 1390), poet, is known from only three sources. These are a Latin memorandum of about 1400 on the last leaf of an unfinished copy of his poem The Vision of Piers Plowman made about the same time (TCD, MS D.4.1 (212)), a cluster of sixteenth-century ascriptions by the antiquary John Bale (d. 1563), and the poem itself. Origins Even the memorandum seems primarily about Langland's parentage, as if this were the object of interest: It was Stacy de Rokayle who was William de Langlond's father; this Stacy was of gentle birth and lived in Shipton- under-Wychwood in Oxfordshire, holding land from Lord le Spenser; the aforesaid William wrote the book called Piers Plowman. Dublin, Trinity College, MS D.4.1 (212) The memorandum is authenticated by knowledgeable local annals dated from 1294 to 1348 in the same hand above it on the page, with clear interest in the Despensers. Extension of that interest to include the poet's family is indicated by a recent discovery (Matheson) that his grandfather Peter de Rokele had been in the service of Hugh le Despenser the younger, indeed had several times been violently and unlawfully active in his interest, and that, having in April 1327 been pardoned for 'adhering' to Despenser, he was within months implicated in a conspiracy to release the captive Edward II. -

Piers Plowman, Anthony Trollope, and Charities Law Jill R

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2009 Nonprofits and Narrative: Piers Plowman, Anthony Trollope, and Charities Law Jill R. Horwitz UCLA School of Law, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/515 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Nonprofit Organizations Law Commons, and the Social Welfare Law Commons Recommended Citation Horwitz, Jill R. "Nonprofits nda Narrative: Piers Plowman, Anthony Trollope, and Charities Law." Mich. St. L. Rev. 2009, no. 4 (2009): 989-1016. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NONPROFITS AND NARRATIVE: PIERS PLOWMAN, ANTHONY TROLLOPE, AND CHARITIES LAW Jill Horwitz* 2009 MICH. ST. L. REV. 989 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ....................................................... 989 INTRODUCTION ...................................... ....... 990 I. LITERATURE IN NONPROFIT LAW: THE VISION OFPIERS PLO WMAN, THE STATUTE OF ELIZABETH, AND AMERICAN CHARITIES LAW ........ 995 A. The Statute of Elizabeth and Piers Plowman.................... 996 B. English and American Charities Law............. ..... 1000 11. NONPROFIT LAW IN LITERATURE: ST. CROSS HOSPITAL AND THE WARDEN ................................. ..... 1005 A. St. Cross Hospital ......................... ....... 1007 B. The Warden .......................................1009 CONCLUSION ................................................. 1015 ABSTRACT What are the narrative possibilities for understanding nonprofit law? Given the porous barriers between nonprofit law and the literature about it, there are many. -

|||GET||| the Middle English Bible a Reassessment 1St Edition

THE MIDDLE ENGLISH BIBLE A REASSESSMENT 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Henry Ansgar Kelly | 9780812248340 | | | | | The Middle English Bible: A Reassessment Thanks for telling us about the problem. If your source is an eBook or an app, those guidelines are different as well. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. I conclude with an account of the most recent developments and trends. The Common Edition New Testament. The Middle English Bible A Reassessment 1st edition issues he raises need rethinking, and it's especially useful to have these arguments, which demand space and time, in the form of a book. New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures. By NT Wright. He is author of many books, including Satan: A Biography. Richard Ullerston d. While there were attempts by the Lollard movement to appropriate or coopt it after the fact, the translation project, which appears to have originated at Oxford University, was wholly orthodox. Learn how to enable JavaScript on The Middle English Bible A Reassessment 1st edition browser. Other editions. Home 1 Books 2. Contact Contact Us Help. Today's New International Version. Psalters 12 in totalincluding the Vespasian Psalter and Eadwine Psalter. It seemed to me that there was need for a The Middle English Bible A Reassessment 1st edition of how it has been regarded over the years, and the points of controversy connected with it at each stage, especially concerning claims for and against its origin as a project of the religious dissident John Wyclif d. It can refer to Jews who turn to religions other than Judaism and non-Jews who Get Started. -

WILLIAM LANGLAND C, 1332

In habit like a hermit' in his works unholy. And through the wide world I went, wonders to hear. But on a May morning, on Malvern Hills^, A marvel befel me ~ sure from Faery it came - 1 had wandered me weary, so weary, I rested me On a broad bank by a merry-sounding bum; And as I lay and leaned and looked into the waters I slumbered in a sleeping, it rippled so merrily, WILLIAM LANGLAND And I dreamed-marvellously. c, 1332 - c. 1400 All the world's weal, aU the world's woe, Truth and trickery, treason and guile. All I saw sleeping. The identity od the author is one of the most fascinating problems attached to English 1 was in a wilderness, wist I not where. Uteiaty scholarship. From scattered allusions in the many manuscripts, it was assumed for And eastward I looked against the sun. a long time that the poet was William Langland, a native of Shropshire! his father perhaps I saw a Tower on an hill, fairly fadiioned. a freeman land-holder or franklin; and he himself later a cleric in the Benedictine convent Beneath it a Dell, and in the Dell a dungeon, , of Malvern. Subsequently he came to London and led a vagabondish life through the rest With deep ditches and dark and dreadful to see, of his days. He was assumed to have a learning of a sort, but he owed it more to wit than And Death and wicked ^irits dwelt therein. to application. Possibly he took minor orders in the Church. -

In William Langland's Piers Plowman and Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales

BETWEEN “ERNEST” AND “GAME”: THE AESTHETICS OF KNOWING AND POETICS OF “WITTE” IN WILLIAM LANGLAND'S PIERS PLOWMAN AND GEOFFREY CHAUCER’S CANTERBURY TALES by SHARITY D. NELSON A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of English and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2013 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Sharity D. Nelson Title: Between “Ernest” and “Game”: The Aesthetics of Knowing and Poetics of “Witte” in William Langland's Piers Plowman and Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of English by: Warren Ginsberg Chair Anne Laskaya Core Member Louise M. Bishop Core Member Kenneth Calhoon Institutional Representative and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation; Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded in September 2013 ii © 2013 Sharity D. Nelson iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Sharity D. Nelson Doctor of Philosophy Department of English September 2013 Title: Between “Ernest” and “Game”: The Aesthetics of Knowing and Poetics of “Witte” in William Langland's Piers Plowman and Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales A common assumption in theories of the aesthetic is that it is a concept and experience that belongs to modernity. However, as Umberto Eco has shown, the aesthetic was a topic of great consideration by medieval thinkers. As this project demonstrates in the study of the poetry of William Langland and Geoffrey Chaucer, the aesthetic was, in fact, a dynamic and complex concept in the Middle Ages that could affirm institutional ideologies even as it challenged them and suggested alternative perspectives for comprehending truth. -

William Langland - Poems

Classic Poetry Series William Langland - poems - Publication Date: 2004 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive William Langland(1330 - 1390) William Langland was born in 1332, probably at Ledbury near the Welsh marshes and may have gone to school at Great Malvern Priory. Although he took minor orders he never actually became a priest. Having later moved to London he apparently eked out his living by singing masses and copying documents. His great work, Piers Plowman, or, more precisely, The Vision of William concerning Piers the Plowman, is an allegorical poem in unrhymed alliterative verse, regarded as the greatest Middle English poem prior to Chaucer. It is both a social satire and a vision of the simple Christian life. The poem consists of three dream visions: (1) in which Holy Church and Lady Meed (representing the temptation of riches) woo the dreamer; (2) in which Piers leads a crowd of penitents in search of St. Truth; and (3) the vision of Do-well (the practice of the virtues), Do-bet (in which Piers becomes the Good Samaritan practicing charity), and Do-best (in which the simple plowman is identified with Christ himself). The 47 extant manuscripts of the poem fall into three groups: the A-text (2,567 lines, c.1362); the B-text, which greatly expands the third vision (7,242 lines, c.1376–77); the C-text, a revision of B (7,357 lines, between 1393 and 1398). Most scholars now believe that at least the A- and B-texts are the work of William Langland, whose biography has been deduced from passages in the poem.