El Yunque National Forest Draft Environmental Impact Statement For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rowley, Marissa (2013) Interspecific Competition Between Prawns in The

Interspecific Competition between Prawns in the Checkhall River Marissa Rowley Dominica 2013 May 18 – June 9 ABSTRACT On the island of Dominica, nature remains virtually untouched by humans. This makes the island an exceptional choice for biological research as well as animal habitats. With its many different ecosystems, numerous animals take refuge throughout the island. Five species of prawns coexist within the Checkhall River on the island of Dominica, two of which lack pincers. In the Checkhall River, I researched competition of prawns for available food sources in different areas of the stream, including shallow areas, deep areas, and waterfall areas. Coconut was tied to fishing line, weighted down with a rock, and used as bait. The bait line was then dropped in chosen areas of the stream and watched for interspecific interactions until a clear winner was present. Multiple trials were held in each designated spot. From the results, it is clear the Macrobrachium species of prawns dominate competition in the Checkhall River. I believe this is because of their larger pincers. Their pincers can be used to obtain and keep hold of a food source and intimidate other species of prawns. This research can be helpful to future biologists studying the behavioral ecology of freshwater prawns. INTRODUCTION Dominica is a relatively small volcanic island located in the Lesser Antillean chain of the Caribbean. Appropriately nicknamed the Nature Island, Dominica is characterized by many different habitats including mountainous terrain, rainforests, waterfalls, lakes, and rivers (Discover Dominica Authority). These different ecosystems make Dominica an exceptional place for field biology research as they remain mostly untouched by humans and modern society. -

Effects of Drought and Hurricane Disturbances on Headwater Distributions of Palaemonid River Shrimp (Macrobrachium Spp.) in the Luquillo Mountains, Puerto Rico

J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc., 2006, 25(1):99–107 Ó 2006 by The North American Benthological Society Effects of drought and hurricane disturbances on headwater distributions of palaemonid river shrimp (Macrobrachium spp.) in the Luquillo Mountains, Puerto Rico Alan P. Covich1 Institute of Ecology, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602-2202 USA 2 3 Todd A. Crowl AND Tamara Heartsill-Scalley Ecology Center and Department of Aquatic, Watershed, and Earth Sciences, Utah State University, Logan, Utah 84322 USA Abstract. Extreme events (hurricanes, floods, and droughts) can influence upstream migration of macroinvertebrates and wash out benthic communities, thereby locally altering food webs and species interactions. We sampled palaemonid river shrimp (Macrobrachium spp.), dominant consumers in headwaters of the Luquillo Mountains of northeastern Puerto Rico, to determine their distributions along an elevational gradient (274–456 m asl) during a series of disturbances (Hurricane Hugo in 1989, a drought in 1994, and Hurricane Georges in 1998) that occurred over a 15-y period (1988À2002). We measured shrimp abundance 3 to 6 times/y in Quebrada Prieta in the Espiritu Santo drainage as part of the Luquillo Long- Term Ecological Research Program. In general, Macrobrachium abundance declined with elevation during most years. The lowest mean abundance of Macrobrachium occurred during the 1994 drought, the driest year in 28 y of record in the Espiritu Santo drainage. Macrobrachium increased in abundance for 6 y following the 1994 drought. In contrast, hurricanes and storm flows had relatively little effect on Macrobrachium abundance. Key words: dispersal, drainage networks, geomorphology, habitat preference, omnivores, prey refugia. Flow-based events often modify the important roles (Covich et al. -

A Migratory Shrimp's Perspective on Habitat Fragmentation in The

A MIGRATORY SHRIMP’S PERSPECTIVE ON HABITAT FRAGMENTATION IN THE NEOTROPICS: EXTENDING OUR KNOWLEDGE FROM PUERTO RICO BY MARCIA N. SNYDER1,3), ELIZABETH P. ANDERSON2,4) and CATHERINE M. PRINGLE1,5) 1) Odum School of Ecology, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602, U.S.A. 2) Global Water for Sustainability Program, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199, U.S.A. ABSTRACT Migratory freshwater fauna depend on longitudinal connectivity of rivers throughout their life cycles. Amphidromous shrimps spend their adult life in freshwater but their larvae develop into juveniles in salt water. River fragmentation resulting from pollution, land use change, damming and water withdrawals can impede dispersal and colonization of larval shrimps. Here we review current knowledge of river fragmentation effects on freshwater amphidromous shrimp in the Neotropics, with a focus on Puerto Rico and Costa Rica. In Puerto Rico, many studies have contributed to our knowledge of the natural history and ecological role of migratory neotropical shrimps, whereas in Costa Rica, studies of freshwater migratory shrimp have just begun. Here we examine research findings from Puerto Rico and the applicability of those findings to continental Costa Rica. Puerto Rico has a relatively large number of existing dams and water withdrawals, which have heavily fragmented rivers. The effects of fragmentation on migratory shrimps’ distribution have been documented on the landscape-scale in Puerto Rico. Over the last decade, dams for hydropower production have been constructed on rivers throughout Costa Rica. In both countries, large dams restrict shrimps from riverine habitat in central highland regions; in Puerto Rico 27% of stream kilometers are upstream of large dams while in Costa Rica 10% of stream kilometers are upstream of dams. -

BIOLÓGICA VENEZUELICA Es Editada Por Dirección Postal De Los Mismos

7 M BIOLÓGICA II VENEZUELICA ^^.«•r-íí-yííT"1 VP >H wv* "V-i-, •^nru-wiA ">^:^;iW SWv^X/^ií. UN I VE RSIDA P CENTRAL DÉ VENEZUELA ^;."rK\'':^>:^:;':••'': ; .-¥•-^>v^:v- ^ACUITAD DE CIENCIAS INSilTÜTO DÉ Z00LOGIA TROPICAL: •RITiTRnTOrr ACTA BIOLÓGICA VENEZUELICA es editada por Dirección postal de los mismos. Deberá suministrar el Instituto de Zoología Tropical, Facultad, de Ciencias se en página aparte el título del trabajo en inglés en de la Universidad Central de Venezuela y tiene por fi caso de no estar el manuscritp elaborado en ese nalidad la publicación de trabajos originales sobre zoo idioma. logía, botánica y ecología. Las descripciones de espe cies nuevas de la flora y fauna venezolanas tendrán Resúmenes: Cada resumen no debe exceder 2 pági prioridad de publicación. Los artículos enviados no de nas tamaño carta escritas a doble espacio. Deberán berán haber sido publicados previamente ni estar sien elaborarse en castellano e ingles, aparecer en este do considerados para tal fin en otras revistas. Los ma mismo orden y en ellos deberá indicarse el objetivo nuscritos deberán elaborarse en castellano o inglés y y los principales resultados y conclusiones de la co no deberán exceder 40 páginas tamaño carta, escritas municación. a doble espacio, incluyendo bibliografía citada, tablas y figuras. Ilustraciones: Todas las ilustraciones deberán ser llamadas "figuras" y numeradas en orden consecuti ACTA BIOLÓGICA VENEZUELICA se edita en vo (Ejemplo Fig. 1. Fig 2a. Fig 3c.) el número, así co cuatro números que constituyen un volumen, sin nin mo también el nombre del autor deberán ser escritos gún compromiso de fecha fija de publicación. -

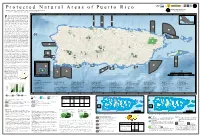

Protected Areas by Management 9

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

Universidade De São Paulo Ffclrp

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FFCLRP - DEPARTAMENTO DE BIOLOGIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM BIOLOGIA COMPARADA Avaliação sistemática de camarões de água doce do gênero Atya Leach, 1816 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Atyidae) por meio de dados moleculares Caio Martins Cruz Alves de Oliveira Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto da USP, como parte das exigências para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências, Área: BIOLOGIA COMPARADA Ribeirão Preto - SP 2017 UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FFCLRP - DEPARTAMENTO DE BIOLOGIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM BIOLOGIA COMPARADA Avaliação sistemática de camarões de água doce do gênero Atya Leach, 1816 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Atyidae) por meio de dados moleculares Caio Martins Cruz Alves de Oliveira Orientador: Prof. Dr. Fernando Luis Medina Mantelatto Co-orientadora: Profa. Dra. Mariana Terossi Rodrigues Mariano Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto da USP, como parte das exigências para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências, Área: BIOLOGIA COMPARADA Versão Original Ribeirão Preto - SP 2017 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. Oliveira, C. M. C. A. “Avaliação sistemática de camarões de água doce do gênero Atya Leach, 1816 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Atyidae) por meio de dados moleculares” Ribeirão Preto, 2017 vii+107p. Dissertação (Mestrado – Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciências. Área de concentração: Biologia Comparada). Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo (FFCLRP-USP). Orientador: Mantelatto, F.L.M.; Co-orientadora: Mariano, M.T.R. -

To See Our Puerto Rico Vacation Planning

DISCOVER PUERTO RICO LEISURE + TRAVEL 2021 Puerto Rico Vacation Planning Guide 1 IT’S TIME TO PLAN FOR PUERTO RICO! It’s time for deep breaths and even deeper dives. For simple pleasures, dramatic sunsets and numerous ways to surround yourself with nature. It’s time for warm welcomes and ice-cold piña coladas. As a U.S. territory, Puerto Rico offers the allure of an exotic locale with a rich, vibrant culture and unparalleled natural offerings, without needing a passport or currency exchange. Accessibility to the Island has never been easier, with direct flights from domestic locations like New York, Charlotte, Dallas, and Atlanta, to name a few. Lodging options range from luxurious beachfront resorts to magical historic inns, and everything in between. High standards of health and safety have been implemented throughout the Island, including local measures developed by the Puerto Rico Tourism Company (PRTC), alongside U.S. Travel Association (USTA) guidelines. Outdoor adventures will continue to be an attractive alternative for visitors looking to travel safely. Home to one of the world’s largest dry forests, the only tropical rainforest in the U.S. National Forest System, hundreds of underground caves, 18 golf courses and so much more, Puerto Rico delivers profound outdoor experiences, like kayaking the iridescent Bioluminescent Bay or zip lining through a canopy of emerald green to the sound of native coquí tree frogs. The culture is equally impressive, steeped in European architecture, eclectic flavors of Spanish, Taino and African origins and a rich history – and welcomes visitors with genuine, warm Island hospitality. Explore the authentic local cuisine, the beat of captivating music and dance, and the bustling nightlife, which blended together, create a unique energy you won’t find anywhere else. -

Guide to Theecological Systemsof Puerto Rico

United States Department of Agriculture Guide to the Forest Service Ecological Systems International Institute of Tropical Forestry of Puerto Rico General Technical Report IITF-GTR-35 June 2009 Gary L. Miller and Ariel E. Lugo The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and national grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD).To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Authors Gary L. Miller is a professor, University of North Carolina, Environmental Studies, One University Heights, Asheville, NC 28804-3299. -

Angel Rodriguez Alvarez a Preliminary Petroglyph

ANGEL RODRIGUEZ ALVAREZ A PRELIMINARY PETROGLYPH SURVEY ALONG THE BLANCO RIVER: PUERTO RICO INTRODUCTION Among the islands that form the Greater and Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico is well known for the quantity and quality of its petroglyphs and pictograph. The different designs and techniques of the rock engravings vary in Puerto Rico even in adjoining sites, or on the same boulder, ledge or wall cave. In Puerto Rico, the study of petroglyphs has been documented in detail since the last century by Pinart (1890), Dumont (1876), and Krug (1876). During the early 1900's, the main study of rock art was made by Stalth (n.d.) and Fewkes (1907); and later by Frasseto (1960)), Rouse (1952, 1949) and Alegría (1941). Recently, several works have been done on this subject, such as the reports by Walker (1983), Martinez (1981) and Dávila (1976). Among these researches, only works of Walker (1983) and Frasseto (1960) deal with the Blanco River petroglyphs. However, the present study differs from the previous works that have been done on this area, because they have dealt with the Blanco River petroglyphs sites primarily on a general level. DESCRIPTION OF THE RESEARCH AREA Puerto Rico has two main physiographic regions, the Coastal Plains and the Mountain Systems. The Sierra de Luquillo Mountains are located at the Northeast of the Island. This Sierra divides the Gurabo River from other rivers that flow toward the Atlantic Ocean. The highest peaks are: El Toro (1,074 meters), El Yunque (1,065 meter), and Pico del Este (1,051 meters). The south slope of El Yunque provides the drainage system for the Blanco River (Galiñanes, 1977:6). -

Wild Silence Skiing the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge Article on Page 10

National Outdoor Leadership School NONpROfIT ORG. 284 Lincoln Street US POSTAGE Lander, WY 82520-2848 PAID www.nols.edu • (800) 710-NOLS pERmIT NO. 81 THE LEADER IN WILDERNESS EDUCATION jACkSON, WY 20 12 3 Expedition Behavior Expedition Skiing Icebergs Skiing Grad Saves Dad’s Life Dad’s Saves Grad of Points Finer The Article on p on Article ge 10 ge A Na Arctic the Skiing tion A r Wildlife l efuge Wild Silence Wild For Alumni of the National Outdoor Leadership School School Leadership Leadership Outdoor Outdoor National National the the of of Alumni Alumni For For Leader Leader THE No.0 No.1 00 26 Vol. Vol. Year 2010 Season Fall • • • • 2 THE Leader mEssagE from the D irEcTor s the calendar recently turned to September, A NOLS completed its 2010 fiscal year and its 45th year of wilderness education . The year was a wonderful one and, by most measures, the most suc- cessful year in the history of the school . We educated a record number of students, adding over 15,000 stu- dents to our alumni base . We raised record philan- thropic support for the NOLS Annual Fund, which THE Leader helped us award record scholarship funds this year . Brad Christensen For the third year in a row, NOLS was named one Thanks to everyone who joined us in Lander last month to celebrate our 45th anniversary! The recap can be Joanne Haines of the best places to work in the country by Outside found on page 19. Publications Manager magazine . We significantly expanded our student base through our Gateway Partners, who have helped riculum more accessible to more people . -

Dendroica Angelae) to INFLUENCE ITS LONG TERM CONSERVATION

ASSESSING THE STATUS, ECOLOGY AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE ELFIN WOODS WARBLER (Dendroica angelae) TO INFLUENCE ITS LONG TERM CONSERVATION FINAL REPORT - July 2004 Prepared by: Carlos A. Delannoy, P.h.D.1 and Verónica Anadón 2 Supported by BP Conservation Programme - Project No.210902 1, 2 University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez Campus Department of Biology Mayagüez, Puerto Rico 00681. Phone: 1-(787)-265-5417 [email protected] 1 [email protected] 2 Project EWWA 2003 1 ASSESSING THE STATUS, ECOLOGY AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE ELFIN WOODS WARBLER (Dendroica angelae) TO INFLUENCE ITS LONG TERM CONSERVATION PROJECT SUMMARY The endemic Elfin Woods Warbler (EWWA) (Dendroica angelae) is found in upland forests and is considered a threatened species. It was discovered in the Luquillo Forest in 1971 and later in Maricao, Carite and Toro Negro Forests. The objectives of this study were to determine the current geographic distribution, habitat occupancy and density of the EWWA. We surveyed EWWA populations from March through May and August through November 2003 in Maricao, Guilarte, Bosque del Pueblo, and Toro Negro Forests. EWWA populations were surveyed in Luquillo and Carite Forests for nine weeks during June and July 2003. Survey routes 0.8 to 3 km in length, with point-count stations spaced 200m apart, were established to sample all habitats 250 to 1030 m in elevation. Counts were limited to 10 minutes per point-count station. Our results indicated that EWWA distribution was limited to populations in Maricao and Luquillo Forests. EWWA in Maricao were located in the following forest types: Exposed Woodland, Dry Slope and Podocarpus Forests at elevations that ranged from 280- 790 m. -

INFRAORDER CARIDEA Dana, 1852

click for previous page - 67 - Local Names: Kwei kung (Thailand), Rebon, Djembret (Indonesia; names used for a mixture of Acetes, penaeid larvae and Mysidacea). Literature: Omori, 1975:69, Figs. 14,30. Distribution: Indo-West Pacific: south coast of China to Malaya, Singapore and Indonesia. Habitat: Depth 9 to 55 m, possibly also shallower. Bottom mud and sand. Marine. Size: Total length 17 to 26 mm , 20 to 34 mm . Interest to Fishery: Omori (1975:69) reported the species from the fish market in Jakarta (Indonesia) and also mentioned it as one of the species of the genus fished commercially in Thailand and Singapore. Sergestes lucens Hansen, 1922 SERG Serg 1 Sergestes lucens Hansen, 1922, Résult.Campagne Sci.Prince Albert I, 64:38,121 Synonymy: Sergestes kishinouyei Nakazawa & Terao, 1915; Sergetes phosphoreus Kishinouye, 1925. FAO Names: Sakura shrimp (En), Chevrette sakura (Fr), Camarón sakura (Sp). Local Names: Sakura ebi (Japan) [Niboshi ebi for the dried product]. Literature: Gordon, 1935:310, Figs.lc,3a,4,5,6a,b,7; Omori, 1969:1-83, textfigs. 1-40, col. Pl. 1. Distribution: Indo-West Pacific: so far only known from Japan (Tokyo, Sagami and Suruga Bays). Habitat: In shallow coastal waters. Planktonic. Marine. Size: Maximum total length 35 to 43 mm , 37 to 48 mm . Interest to Fishery: Notwithstanding the restricted area of the species, it "is one of the commercially important shrimps in Japan, and is one of the few planktonic organisms which [are] utilized by Man directly" (Omori, 1969:l); the annual landing around 1969 was 4 000 to 7 000 t.