Due to Limited Communications, This Motion Is Filed in Advance of Mr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global War on Terror

SADAT MACRO 9/14/2009 8:38:06 PM A PRESUMPTION OF GUILT: THE UNLAWFUL ENEMY COMBATANT AND THE U.S. WAR ON TERROR * LEILA NADYA SADAT I. INTRODUCTION Since the advent of the so-called “Global War on Terror,” the United States of America has responded to the crimes carried out on American soil that day by using or threatening to use military force against Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, North Korea, Syria, and Pakistan. The resulting projection of American military power resulted in the overthrow of two governments – the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, the fate of which remains uncertain, and Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq – and “war talk” ebbs and flows with respect to the other countries on the U.S. government’s “most wanted” list. As I have written elsewhere, the Bush administration employed a legal framework to conduct these military operations that was highly dubious – and hypocritical – arguing, on the one hand, that the United States was on a war footing with terrorists but that, on the other hand, because terrorists are so-called “unlawful enemy combatants,” they were not entitled to the protections of the laws of war as regards their detention and treatment.1 The creation of this euphemistic and novel term – the “unlawful enemy combatant” – has bewitched the media and even distinguished justices of the United States Supreme Court. It has been employed to suggest that the prisoners captured in this “war” are not entitled to “normal” legal protections, but should instead be subjected to a régime d’exception – an extraordinary regime—created de novo by the Executive branch (until it was blessed by Congress in the Military * Henry H. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 Amnesty International's Concerns ..................................................................................... 3 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 5 Arrests and detentions ........................................................................................................ 7 ISRAEL AND THE OCCUPIED TERRITORIES ................................................................ 9 Regulations governing detention ........................................................................................ 9 The Landau Commission and the failure of judicial safeguards ................................. 11 Extending the guidelines or exceptional dispensations? ................................................ 14 Methods of torture ............................................................................................................ 15 Torture and ill-treatment: the practice ............................................................................. 17 THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY .................................................................................... 22 Regulations governing detention ...................................................................................... 22 Arbitrary political detentions in the Gaza Strip .............................................................. -

Hearing for Majid Khan

C05403115 o (b)(1) (b)(3) Verbatim Transcript of Combatant Status Review Tribnnal Hearing for ISN 10020 OPENING PRESIDENT: This hearing shall come to order. RECORDER: This Tribunal is being conducted at 08:42 on 15 April 2007 on board U.S. Naval Base Guantanarno Bay, Cuba. The following personnel are present: Colonel United States Air Force, President, Commander United States Navy, Member, Lieutenant Colonel United States Air Force, Member, Major United States Air Force, Personal Representative, Sergeant First Class United States Army, Reporter, Major_United States Air Force, Recorder. Lieutenant Colonel_is the Judge Advocate member ofthe Tribunal. OATH SESSION 1 RECORDER: All rise. PRESIDENT: The Recorder will be sworn. Do you, Major-swear or affirm that you will faithfully perform the duties as ~signed in this Tribunal, so help you God? RECORDER: I do. PRESIDENT: The Reporter will now be sworn. The Recorder will administer the oath. RECORDER: Do you, Sergeant First Class swear that you will faithfully discharge your duties as Reporter assigned in this Tribunal, so help you God? REPORTER: [ do. PRESIDENT: We'll take a briefrecess while the Detainee is brought into the room. RECORDER: The time is 08:43 on IS Apri12007. This Tribunal is now in recess. All rise. [All personnel depart the room.] CONVENING AUTHORITY RECORDER: [All personnel return into the room at 08:48.] All rise. PRESIDENT: This hearing will come to order. You may be seated. Good morning. DETAINEE: Good morning. How are you guys doing? ISN # 10020 Enclosure (3) Page1 of50 C05403115 PRESIDENT: Very good, fine, thank you. This Tribunal is convened by order ofthe Director, Combatant Status Review Tribunals under the provisions ofhis Order of 12 February 2007. -

True and False Confessions: the Efficacy of Torture and Brutal

Chapter 7 True and False Confessions The Efficacy of Torture and Brutal Interrogations Central to the debate on the use of “enhanced” interrogation techniques is the question of whether those techniques are effective in gaining intelligence. If the techniques are the only way to get actionable intelligence that prevents terrorist attacks, their use presents a moral dilemma for some. On the other hand, if brutality does not produce useful intelligence — that is, it is not better at getting information than other methods — the debate is moot. This chapter focuses on the effectiveness of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation technique program. There are far fewer people who defend brutal interrogations by the military. Most of the military’s mistreatment of captives was not authorized in detail at high levels, and some was entirely unauthorized. Many military captives were either foot soldiers or were entirely innocent, and had no valuable intelligence to reveal. Many of the perpetrators of abuse in the military were young interrogators with limited training and experience, or were not interrogators at all. The officials who authorized the CIA’s interrogation program have consistently maintained that it produced useful intelligence, led to the capture of terrorist suspects, disrupted terrorist attacks, and saved American lives. Vice President Dick Cheney, in a 2009 speech, stated that the enhanced interrogation of captives “prevented the violent death of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of innocent people.” President George W. Bush similarly stated in his memoirs that “[t]he CIA interrogation program saved lives,” and “helped break up plots to attack military and diplomatic facilities abroad, Heathrow Airport and Canary Wharf in London, and multiple targets in the United States.” John Brennan, President Obama’s recent nominee for CIA director, said, of the CIA’s program in a televised interview in 2007, “[t]here [has] been a lot of information that has come out from these interrogation procedures. -

America's Illicit Affair with Torture

AMERICA’S ILLICIT AFFAIR WITH TORTURE David Luban1 Keynote address to the National Consortium of Torture Treatment ProGrams Washington, D.C., February 13, 2013 I am deeply honored to address this Group. The work you do is incredibly important, sometimes disheartening, and often heartbreaking. Your clients and patients have been alone and terrified on the dark side of the moon. You help them return to the company of humankind on Earth. To the outside world, your work is largely unknown and unsung. Before saying anything else, I want to salute you for what you do and offer you my profound thanks. I venture to guess that all the people you treat, or almost all, come from outside the United States. Many of them fled to America seekinG asylum. In the familiar words of the law, they had a “well-founded fear of persecution”—well- founded because their own Governments had tortured them. They sought refuge in the United States because here at last they would be safe from torture. Largely, they were right—although this morninG I will suGGest that if we peer inside American prisons, and understand that mental torture is as real as physical torture, they are not as riGht as they hoped. But it is certainly true that the most obvious forms of political torture and repression are foreign to the United States. After all, our constitution forbids cruel and unusual punishments, and our Supreme Court has declared that coercive law enforcement practices that “shock the conscience” are unconstitutional. Our State Department monitors other countries for torture. -

Download Article

tHe ABU oMAr CAse And “eXtrAordinAry rendition” Caterina Mazza Abstract: In 2003 Hassan Mustafa Osama Nasr (known as Abu Omar), an Egyptian national with a recognised refugee status in Italy, was been illegally arrested by CIA agents operating on Italian territory. After the abduction he was been transferred to Egypt where he was in- terrogated and tortured for more than one year. The story of the Milan Imam is one of the several cases of “extraordinary renditions” imple- mented by the CIA in cooperation with both European and Middle- Eastern states in order to overwhelm the al-Qaeda organisation. This article analyses the particular vicissitude of Abu Omar, considered as a case study, and to face different issues linked to the more general phe- nomenon of extra-legal renditions thought as a fundamental element of US counter-terrorism strategies. Keywords: extra-legal detention, covert action, torture, counter- terrorism, CIA Introduction The story of Abu Omar is one of many cases which the Com- mission of Inquiry – headed by Dick Marty (a senator within the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe) – has investi- gated in relation to the “extraordinary rendition” programme im- plemented by the CIA as a counter-measure against the al-Qaeda organisation. The programme consists of secret and illegal arrests made by the police or by intelligence agents of both European and Middle-Eastern countries that cooperate with the US handing over individuals suspected of being involved in terrorist activities to the CIA. After their “arrest,” suspects are sent to states in which the use of torture is common such as Egypt, Morocco, Syria, Jor- dan, Uzbekistan, Somalia, Ethiopia.1 The practice of rendition, in- tensified over the course of just a few years, is one of the decisive and determining elements of the counter-terrorism strategy planned 134 and approved by the Bush Administration in the aftermath of the 11 September 2001 attacks. -

Homeland Security Implications of Radicalization

THE HOMELAND SECURITY IMPLICATIONS OF RADICALIZATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, INFORMATION SHARING, AND TERRORISM RISK ASSESSMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SEPTEMBER 20, 2006 Serial No. 109–104 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 35–626 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman DON YOUNG, Alaska BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas LORETTA SANCHEZ, California CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut NORMAN D. DICKS, Washington JOHN LINDER, Georgia JANE HARMAN, California MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana PETER A. DEFAZIO, Oregon TOM DAVIS, Virginia NITA M. LOWEY, New York DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JIM GIBBONS, Nevada Columbia ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut ZOE LOFGREN, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON-LEE, Texas STEVAN PEARCE, New Mexico BILL PASCRELL, JR., New Jersey KATHERINE HARRIS, Florida DONNA M. CHRISTENSEN, U.S. Virgin Islands BOBBY JINDAL, Louisiana BOB ETHERIDGE, North Carolina DAVE G. REICHERT, Washington JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island MICHAEL MCCAUL, Texas KENDRICK B. MEEK, Florida CHARLIE DENT, Pennsylvania GINNY BROWN-WAITE, Florida SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, INFORMATION SHARING, AND TERRORISM RISK ASSESSMENT ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut, Chairman CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania ZOE LOFGREN, California MARK E. -

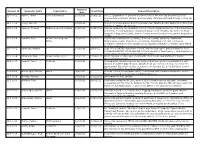

Requests Report

Received Request ID Requester Name Organization Closed Date Request Description Date 12-F-0001 Vahter, Tarmo Eesti Ajalehed AS 10/3/2011 3/19/2012 All U.S. Department of Defense documents about the meeting between Estonian president Arnold Ruutel (Ruutel) and Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney on July 19, 1991. 12-F-0002 Jeung, Michelle - 10/3/2011 - Copies of correspondence from Congresswoman Shelley Berkley and/or her office from January 1, 1999 to the present. 12-F-0003 Lemmer, Thomas McKenna Long & Aldridge 10/3/2011 11/22/2011 Records relating to the regulatory history of the following provisions of the Department of Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS), the former Defense Acquisition Regulation (DAR), and the former Armed Services Procurement Regulation (ASPR). 12-F-0004 Tambini, Peter Weitz Luxenberg Law 10/3/2011 12/12/2011 Documents relating to the purchase, delivery, testing, sampling, installation, Office maintenance, repair, abatement, conversion, demolition, removal of asbestos containing materials and/or equipment incorporating asbestos-containing parts within its in the Pentagon. 12-F-0005 Ravnitzky, Michael - 10/3/2011 2/9/2012 Copy of the contract statement of work, and the final report and presentation from Contract MDA9720110005 awarded to the University of New Mexico. I would prefer to receive these documents electronically if possible. 12-F-0006 Claybrook, Rick Crowell & Moring LLP 10/3/2011 12/29/2011 All interagency or other agreements with effect to use USA Staffing for human resources management. 12-F-0007 Leopold, Jason Truthout 10/4/2011 - All documents revolving around the decision that was made to administer the anti- malarial drug MEFLOQUINE (aka LARIAM) to all war on terror detainees held at the Guantanamo Bay prison facility as stated in the January 23, 2002, Infection Control Standard Operating Procedure (SOP). -

Military Commissions: a Place Outside the Law’S Reach

MILITARY COMMISSIONS: A PLACE OUTSIDE THE LAW’S REACH JANET COOPER ALEXANDER* “We have turned our backs on the law and created what we believed was a place outside the law’s reach.” Colonel Morris D. Davis, former chief prosecutor of the Guantánamo military commissions1 Ten years after 9/11, it is hard to remember that the decision to treat the attacks as the trigger for taking the country to a state of war was not inevitable. Previous acts of terrorism had been investigated and prosecuted as crimes, even when they were carried out or planned by al Qaeda.2 But on September 12, 2001, President Bush pronounced the attacks “acts of war,”3 and he repeatedly defined himself as a “war president.”4 The war * Frederick I. Richman Professor of Law, Stanford Law School. I would like to thank participants at the 2011 Childress Lecture at Saint Louis University School of Law and a Stanford Law School faculty workshop for their comments, and Nicolas Martinez for invaluable research assistance. 1 Ed Vulliamy, Ten Years On, Former Chief Prosecutor at Guantanamo Slams ‘Camp of Torture,’ OBSERVER, Oct. 30, 2011, at 29. 2 Previous al Qaeda attacks that were prosecuted as crimes include the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center, the Manila Air (or Bojinka) plot to blow up a dozen jumbo jets, and the 1998 embassy bombings in East Africa. Mary Jo White, Prosecuting Terrorism in New York, MIDDLE E.Q., Spring 2001, at 11, 11–14; see also Christopher S. Wren, U.S. Jury Convicts 3 in a Conspiracy to Bomb Airliners, N.Y. -

Sec 5.1~Abuse of Prisoners As Torture

1 5. Substantive Legal Assessment 5.1 Abuse of Prisoners as Torture and War Crimes under Sec. 8 of the CCIL and International Law The crimes described above against detainees at Abu Ghraib and the plaintiffs al Qahtani and Mowsboush constitute torture and war crimes under German and international criminal law. Therefore, sufficient evidence exists of criminality under Sec. 8 I nos. 3 and 9 CCIL. The following will provide a detailed legal analysis of the prohibitions in the CCIL and international law that were violated by the above-described acts. First, it will note the way in which two high-ranking members of the U.S. government dealt with the traditional torture techniques of “water boarding” and “longtime standing,” which is significant from the plaintiff’s perspective. In their publicly documented statements, both of government officials reveal a high degree of cynicism, coupled with ignorance of historical, legal and medical contexts. “Water Boarding” and “Longtime Standing” In the course of an interview on 24 October 2006, the Vice President of the United States, Richard Cheney, asked by radio reporter Scott Hennen whether “a dunk in water is a no- brainer if it can save lives,” gave the following answer: “It's a no-brainer for me, but for a 2 while there, I was criticized as being the ‘Vice President for torture.’ We don't torture. That's not what we're involved in. We live up to our obligations in international treaties that we're party to.” Cheney was the first member of the Bush government to admit that “water boarding” had been used in the case of detainee Khalid Scheikh Mohammed and other high-ranking al Quaeda members. -

2018.12.03 Bonner Soufan Complaint Final for Filing 4

Case 1:18-cv-11256 Document 1 Filed 12/03/18 Page 1 of 19 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - X : : RAYMOND BONNER and ALEX GIBNEY, Case No. 18-cv-11256 : Plaintiffs, : : -against- : : COMPLAINT CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY, : : Defendant. : : - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - X INTRODUCTION 1. This complaint for declaratory relief arises out of actions taken by defendant Central Intelligence Agency (“CIA”) that have effectively gagged the speech of former Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”) Special Agent Ali Soufan in violation of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. The gag imposed upon Mr. Soufan is part of a well-documented effort by the CIA to mislead the American public about the supposedly valuable effects of torture, an effort that has included deceptive and untruthful statements made by the CIA to Executive and Legislative Branch leaders. On information and belief, the CIA has silenced Mr. Soufan because his speech would further refute the CIA’s false public narrative about the efficacy of torture. 2. In 2011, Mr. Soufan published a personal account of his service as a top FBI interrogator in search of information about al-Qaeda before and after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Soufan’s original manuscript discussed, among other things, his role in the FBI’s interrogation of a high-value detainee named Zayn Al-Abidin Muhammed Husayn, more commonly known as Abu Zubaydah. Soufan was the FBI’s lead interrogator of Zubaydah while he was being held at Case 1:18-cv-11256 Document 1 Filed 12/03/18 Page 2 of 19 a secret CIA black site. -

The Taint of Torture: the Roles of Law and Policy in Our Descent to the Dark Side

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2012 The Taint of Torture: The Roles of Law and Policy in Our Descent to the Dark Side David Cole Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 12-054 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/908 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2040866 49 Hous. L. Rev. 53-69 (2012) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Do Not Delete 4/8/2012 2:44 AM ARTICLE THE TAINT OF TORTURE: THE ROLES OF LAW AND POLICY IN OUR DESCENT TO THE DARK SIDE David Cole* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 53 II.TORTURE AND CRUELTY: A MATTER OF LAW OR POLICY? ....... 55 III.ACCOUNTABILITY AND LEGAL VIOLATIONS ............................. 62 IV.THE LAW AND POLICY OF DETENTION AND TARGETING.......... 64 I. INTRODUCTION Philip Zelikow has provided a fascinating account of how officials in the U.S. government during the “War on Terror” authorized torture and cruel treatment of human beings whom they labeled “high value al Qaeda detainee[s],” “enemy combatants,” or “the worst of the worst.”1 Professor Zelikow * Professor, Georgetown Law. 1. Philip Zelikow, Codes of Conduct for a Twilight War, 49 HOUS. L. REV. 1, 22–24 (2012) (providing an in-depth analysis of the decisions made by the Bush Administration in implementing interrogation policies and practices in the period immediately following September 11, 2001); see Military Commissions Act of 2006, Pub.