View Issue As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HUMANISM Religious Practices

HUMANISM Religious Practices . Required Daily Observances . Required Weekly Observances . Required Occasional Observances/Holy Days Religious Items . Personal Religious Items . Congregate Religious Items . Searches Requirements for Membership . Requirements (Includes Rites of Conversion) . Total Membership Medical Prohibitions Dietary Standards Burial Rituals . Death . Autopsies . Mourning Practices Sacred Writings Organizational Structure . Headquarters Location . Contact Office/Person History Theology 1 Religious Practices Required Daily Observance No required daily observances. Required Weekly Observance No required weekly observances, but many Humanists find fulfillment in congregating with other Humanists on a weekly basis (especially those who characterize themselves as Religious Humanists) or other regular basis for social and intellectual engagement, discussions, book talks, lectures, and similar activities. Required Occasional Observances No required occasional observances, but some Humanists (especially those who characterize themselves as Religious Humanists) celebrate life-cycle events with baby naming, coming of age, and marriage ceremonies as well as memorial services. Even though there are no required observances, there are several days throughout the calendar year that many Humanists consider holidays. They include (but are not limited to) the following: February 12. Darwin Day: This marks the birthday of Charles Darwin, whose research and findings in the field of biology, particularly his theory of evolution by natural selection, represent a breakthrough in human knowledge that Humanists celebrate. First Thursday in May. National Day of Reason: This day acknowledges the importance of reason, as opposed to blind faith, as the best method for determining valid conclusions. June 21 - Summer Solstice. This day is also known as World Humanist Day and is a celebration of the longest day of the year. -

Hearing for Majid Khan

C05403115 o (b)(1) (b)(3) Verbatim Transcript of Combatant Status Review Tribnnal Hearing for ISN 10020 OPENING PRESIDENT: This hearing shall come to order. RECORDER: This Tribunal is being conducted at 08:42 on 15 April 2007 on board U.S. Naval Base Guantanarno Bay, Cuba. The following personnel are present: Colonel United States Air Force, President, Commander United States Navy, Member, Lieutenant Colonel United States Air Force, Member, Major United States Air Force, Personal Representative, Sergeant First Class United States Army, Reporter, Major_United States Air Force, Recorder. Lieutenant Colonel_is the Judge Advocate member ofthe Tribunal. OATH SESSION 1 RECORDER: All rise. PRESIDENT: The Recorder will be sworn. Do you, Major-swear or affirm that you will faithfully perform the duties as ~signed in this Tribunal, so help you God? RECORDER: I do. PRESIDENT: The Reporter will now be sworn. The Recorder will administer the oath. RECORDER: Do you, Sergeant First Class swear that you will faithfully discharge your duties as Reporter assigned in this Tribunal, so help you God? REPORTER: [ do. PRESIDENT: We'll take a briefrecess while the Detainee is brought into the room. RECORDER: The time is 08:43 on IS Apri12007. This Tribunal is now in recess. All rise. [All personnel depart the room.] CONVENING AUTHORITY RECORDER: [All personnel return into the room at 08:48.] All rise. PRESIDENT: This hearing will come to order. You may be seated. Good morning. DETAINEE: Good morning. How are you guys doing? ISN # 10020 Enclosure (3) Page1 of50 C05403115 PRESIDENT: Very good, fine, thank you. This Tribunal is convened by order ofthe Director, Combatant Status Review Tribunals under the provisions ofhis Order of 12 February 2007. -

True and False Confessions: the Efficacy of Torture and Brutal

Chapter 7 True and False Confessions The Efficacy of Torture and Brutal Interrogations Central to the debate on the use of “enhanced” interrogation techniques is the question of whether those techniques are effective in gaining intelligence. If the techniques are the only way to get actionable intelligence that prevents terrorist attacks, their use presents a moral dilemma for some. On the other hand, if brutality does not produce useful intelligence — that is, it is not better at getting information than other methods — the debate is moot. This chapter focuses on the effectiveness of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation technique program. There are far fewer people who defend brutal interrogations by the military. Most of the military’s mistreatment of captives was not authorized in detail at high levels, and some was entirely unauthorized. Many military captives were either foot soldiers or were entirely innocent, and had no valuable intelligence to reveal. Many of the perpetrators of abuse in the military were young interrogators with limited training and experience, or were not interrogators at all. The officials who authorized the CIA’s interrogation program have consistently maintained that it produced useful intelligence, led to the capture of terrorist suspects, disrupted terrorist attacks, and saved American lives. Vice President Dick Cheney, in a 2009 speech, stated that the enhanced interrogation of captives “prevented the violent death of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of innocent people.” President George W. Bush similarly stated in his memoirs that “[t]he CIA interrogation program saved lives,” and “helped break up plots to attack military and diplomatic facilities abroad, Heathrow Airport and Canary Wharf in London, and multiple targets in the United States.” John Brennan, President Obama’s recent nominee for CIA director, said, of the CIA’s program in a televised interview in 2007, “[t]here [has] been a lot of information that has come out from these interrogation procedures. -

Holidays and Observances, 2020

Holidays and Observances, 2020 For Use By New Jersey Libraries Made by Allison Massey and Jeff Cupo Table of Contents A Note on the Compilation…………………………………………………………………….2 Calendar, Chronological……………….…………………………………………………..…..6 Calendar, By Group…………………………………………………………………………...17 Ancestries……………………………………………………....……………………..17 Religion……………………………………………………………………………….19 Socio-economic……………………………………………………………………….21 Library……………………………………...…………………………………….…...22 Sources………………………………………………………………………………....……..24 1 A Note on the Compilation This listing of holidays and observances is intended to represent New Jersey’s diverse population, yet not have so much information that it’s unwieldy. It needed to be inclusive, yet practical. As such, determinations needed to be made on whose holidays and observances were put on the calendar, and whose were not. With regards to people’s ancestry, groups that made up 0.85% of the New Jersey population (approximately 75,000 people) and higher, according to Census data, were chosen. Ultimately, the cut-off needed to be made somewhere, and while a round 1.0% seemed a good fit at first, there were too many ancestries with slightly less than that. 0.85% was significantly higher than any of the next population percentages, and so it made a satisfactory threshold. There are 20 ancestries with populations above 75,000, and in total they make up 58.6% of the New Jersey population. In terms of New Jersey’s religious landscape, the population is 67% Christian, 18% Unaffiliated (“Nones”), and 12% Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, and Hindu. These six religious affiliations, which add up to 97% of the NJ population, were chosen for the calendar. 2% of the state is made up of other religions and faiths, but good data on those is lacking. -

Challenge to Socialism Formerly American Medicine and the Political Scene

MARJORIE SHEARON CHALLENGE TO SOCIALISM FORMERLY AMERICAN MEDICINE AND THE POLITICAL SCENE Vol. IV, No. 36 November 16, 1950 81st Congress, Second Session In Outrageous Move With complete disregard United States Menaced The United States is Truman Appoints Anna for the people's man- Should Have only Most fighting for its very life. Rosenberg Assistant date, President Truman Trusted Persons in Every person selected Secretary pf Defense on November 9 announ- National Defense Jobs for a high position in ced he would appoint a the Defense Department top New Dealer, Mrs. Anna M. Rosenberg, to be should be chosen in the national interest. Every Assistant Secretary of Defense. Despite the na- such person should be of unquestioned loyalty and tional repudiation of the New-Fair Deal at the integrity and should have a long record of unsel- polls, the President saw fit to make an interim fish public service. Every such person should be appointment which surprised, shocked, and cha- an American through and through. There is no grined many persons. It was even more trans- place in the Defense Department for persons who parent that Defense Secretary George Marshall have flirted with Communist collaborators and had had "Mrs. Fix-It," as she has been called, who have advocated the establishment of State planted on his staff. The Chicago Tribune of Nov- Socialism in the United States. ember 13 suggests that Presidential adviser John Because of the seriousness of the times and R. Steelman, who had planned to go into business the significance of this appointment, the Editor has with Mrs. -

Homeland Security Implications of Radicalization

THE HOMELAND SECURITY IMPLICATIONS OF RADICALIZATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, INFORMATION SHARING, AND TERRORISM RISK ASSESSMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SEPTEMBER 20, 2006 Serial No. 109–104 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 35–626 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman DON YOUNG, Alaska BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas LORETTA SANCHEZ, California CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut NORMAN D. DICKS, Washington JOHN LINDER, Georgia JANE HARMAN, California MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana PETER A. DEFAZIO, Oregon TOM DAVIS, Virginia NITA M. LOWEY, New York DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JIM GIBBONS, Nevada Columbia ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut ZOE LOFGREN, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON-LEE, Texas STEVAN PEARCE, New Mexico BILL PASCRELL, JR., New Jersey KATHERINE HARRIS, Florida DONNA M. CHRISTENSEN, U.S. Virgin Islands BOBBY JINDAL, Louisiana BOB ETHERIDGE, North Carolina DAVE G. REICHERT, Washington JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island MICHAEL MCCAUL, Texas KENDRICK B. MEEK, Florida CHARLIE DENT, Pennsylvania GINNY BROWN-WAITE, Florida SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, INFORMATION SHARING, AND TERRORISM RISK ASSESSMENT ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut, Chairman CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania ZOE LOFGREN, California MARK E. -

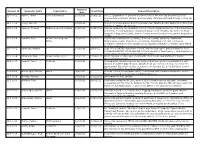

Requests Report

Received Request ID Requester Name Organization Closed Date Request Description Date 12-F-0001 Vahter, Tarmo Eesti Ajalehed AS 10/3/2011 3/19/2012 All U.S. Department of Defense documents about the meeting between Estonian president Arnold Ruutel (Ruutel) and Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney on July 19, 1991. 12-F-0002 Jeung, Michelle - 10/3/2011 - Copies of correspondence from Congresswoman Shelley Berkley and/or her office from January 1, 1999 to the present. 12-F-0003 Lemmer, Thomas McKenna Long & Aldridge 10/3/2011 11/22/2011 Records relating to the regulatory history of the following provisions of the Department of Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS), the former Defense Acquisition Regulation (DAR), and the former Armed Services Procurement Regulation (ASPR). 12-F-0004 Tambini, Peter Weitz Luxenberg Law 10/3/2011 12/12/2011 Documents relating to the purchase, delivery, testing, sampling, installation, Office maintenance, repair, abatement, conversion, demolition, removal of asbestos containing materials and/or equipment incorporating asbestos-containing parts within its in the Pentagon. 12-F-0005 Ravnitzky, Michael - 10/3/2011 2/9/2012 Copy of the contract statement of work, and the final report and presentation from Contract MDA9720110005 awarded to the University of New Mexico. I would prefer to receive these documents electronically if possible. 12-F-0006 Claybrook, Rick Crowell & Moring LLP 10/3/2011 12/29/2011 All interagency or other agreements with effect to use USA Staffing for human resources management. 12-F-0007 Leopold, Jason Truthout 10/4/2011 - All documents revolving around the decision that was made to administer the anti- malarial drug MEFLOQUINE (aka LARIAM) to all war on terror detainees held at the Guantanamo Bay prison facility as stated in the January 23, 2002, Infection Control Standard Operating Procedure (SOP). -

Meeting Ideas

The MAAF Network Selected Meeting Ideas Version 20120417 This document provides some initial meeting ideas. Running a group involves leadership, succession planning, finance, scheduling, logistics, and other considerations that are important but not covered here. Consider requesting a group running guide from the Secular Student Alliance and/or the American Humanist Association. Also look at other organizations listed on the MAAF network page for great ideas or coaching. Below are listed several types of meetings to consider putting on the schedule. For each meeting, take 5‐10 minutes to introduce the group, recognize new members, and ask for input from the group (feedback on events, new ideas, personal news). Service Project: Clean a road, plant a garden, build a house, hand out food… Service projects are by far the most positive and impactful activities for a local group. It can be fun and rewarding, and charitable work does great things to eradicate negative perceptions of atheists. Book Club: This involves 1‐3 members who are familiar with a certain book presenting the main concepts and a few questions. The other members ask questions about the book and discuss key concepts. Note that it is important that members not feel obligated to read the book. This allows the group to learn and limits loss of participation due to busy schedules. Current events: Have individuals bring in news clippings to discuss among the group. It's best to pick a topic – ethics, atheism, cosmology, medicine, etc – just focus the discussion. Also see MAAF's Atheists in Foxholes news and events calendar (under 'community' on the site). -

Military Commissions: a Place Outside the Law’S Reach

MILITARY COMMISSIONS: A PLACE OUTSIDE THE LAW’S REACH JANET COOPER ALEXANDER* “We have turned our backs on the law and created what we believed was a place outside the law’s reach.” Colonel Morris D. Davis, former chief prosecutor of the Guantánamo military commissions1 Ten years after 9/11, it is hard to remember that the decision to treat the attacks as the trigger for taking the country to a state of war was not inevitable. Previous acts of terrorism had been investigated and prosecuted as crimes, even when they were carried out or planned by al Qaeda.2 But on September 12, 2001, President Bush pronounced the attacks “acts of war,”3 and he repeatedly defined himself as a “war president.”4 The war * Frederick I. Richman Professor of Law, Stanford Law School. I would like to thank participants at the 2011 Childress Lecture at Saint Louis University School of Law and a Stanford Law School faculty workshop for their comments, and Nicolas Martinez for invaluable research assistance. 1 Ed Vulliamy, Ten Years On, Former Chief Prosecutor at Guantanamo Slams ‘Camp of Torture,’ OBSERVER, Oct. 30, 2011, at 29. 2 Previous al Qaeda attacks that were prosecuted as crimes include the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center, the Manila Air (or Bojinka) plot to blow up a dozen jumbo jets, and the 1998 embassy bombings in East Africa. Mary Jo White, Prosecuting Terrorism in New York, MIDDLE E.Q., Spring 2001, at 11, 11–14; see also Christopher S. Wren, U.S. Jury Convicts 3 in a Conspiracy to Bomb Airliners, N.Y. -

Hard Cor News Vol. 1 #2

Volume 1, Issue 5 ~ May 15, 2010 New Billboard Design Now Available Because Internet discussion has revealed that some people are getting tired of the billboard image using the blue sky and fluffy white clouds, which has been in use since January 2008, the UnitedCoR board of directors has now approved a fresh new graphic design. It is in direct response to online suggestions that a sunrise or sunset might look good. This new design can be used either with the slogan below or with ―Are you good without God? Millions are.‖ Effective immediately, therefore, local CoRs now have this or the blue-sky design available as options. And, of course, the local CoR URL will be placed where it says ―UnitedCoR.org.‖ (Special thanks to Lisa Zangerl of the American Humanist Association for the graphic design.) Despite, however, these calls by some to replace the blue-sky design, the original remains popular with other people. For example, the following message was received via Detroit CoR from Murray Suters in Sydney, Australia. I read with interest your bus campaign. Unfortunately our transport system has a neutral advertising policy. No church ads but also no secular adds either. In Australia we are currently fighting a federal government decision to federally fund the allocation of chaplains into all public schools. I was thinking that a way of fundraising was to print up a number of bumper stickers and sell them to my fellow atheists. I then saw you ads on the sides of the buses. 1 I would like your permission to use your artwork. -

Maurice Sugar Papers

THE MAURICE SUGAR COLLECTION Papers, 1907-1973 58 1/2 Linear Feet Accession Number 232 Maurice Sugar was one of the first American lawyers to become what is now known as a "Labor Lawyer." Before he was made Chief Legal Counsel of the United Automobile Workers, a post he held between 1937 and 1948, he had practiced as a labor lawyer and defender of the poor since 1914. Born in Brimley, Michigan in 1891, he was educated in the Detroit school system. He graduated from the University of Michigan Law School where he was Editor of the Michigan Law Review. In 1914 he and Jane Mayer were married. She later became Supervisor of Elementary School Physical Education for the City of Detroit. Sugar's first client in 1914 was the Detroit Typographical Union (AFL), and before his work with the UAW he represented nearly all Detroit area unions including the Detroit and Wayne County Federations of Labor (AFL) and various AFL international unions. During the Tool and Die Makers Strike of 1913 he handled over two-hundred cases in the courts. During World War I Sugar was indicted and convicted in a conspiracy trial (1917-1918), as he was a pacifist, but he was subsequently readmitted to the bar and pardoned. Active during his youth in the Socialist Party he later became an important spokesman for what were then considered "left wing" causes, including civil rights and racial equality. He was one of the founders of the National Lawyers Guild and an early advocate of pensions, unemployment compensation, social security and other such measures. -

View Issue As

national lawyers guild Volume 68 Number 3 Fall 2011 Promises and Challenges: 129 The Tunisian Revolution of 2010-2011 Delegation of Attorneys to Tunisia from: National Lawyers Guild (US), Haldane Society of Socialist Lawyers (UK),and Mazlumder (Turkey) Brief of Amicus Curiae in 174 Support of Ward Churchill Cheri J. Deatsch & Heidi Boghosian Book Review: Breeding Ground: 189 Afghanistan and the Origins of Islamist Terrorism Marjorie Cohn editor’s preface This issue begins with a study of the recent revolution in Tunisia titled, “Promises and Challenges: The Tunisian Revolution of 2010-2011.” In March, 2011 a group of Guild members joined an international delegation to Tunisia to investigate the causes and consequences of the recent deposition of Tuni- sian strongman Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali. The report of this delegation is an exhaustive and remarkably engaging story of a bottom-up spontaneous revo- lution against a repressive autocratic regime propped up by western powers, who found Ben-Ali an eager ally in the “global war on terror.” The revolution in Tunisia is one of the seminal events of the great “Arab Spring” of 2011, a world-historical year that will forever be remembered for the uprisings that occurred throughout the Islamic world. This report serves as a contemporary account of the Tunisian revolution written from an anti-imperialist perspec- tive by human rights-minded legal researchers during its immediate aftermath, many of whose sources both lived through and participated in events that have changed history. The second feature in this issue is the Guild’s latest amicus brief on behalf of Ward Churchill.