An Examination of Three Attorneys Who Represented

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hollywood Blacklisting

Hollywood Blacklisting Cierra Hargrove April 27, 2018 !1 Cierra Hargrove Mr. Brant Global Studies 5-27-18 Hollywood Blacklisting In the aftermath of World War II, America was still recovering from the losses of the war along with the rest of the world. Around 1945, The United States entered into a “cold war” with Russia which affected many social and political beliefs within the U.S. Along with a fear of the Soviets, came a great fear of Communism among the government and the people. The government took many actions to prevent the spread of Communism into the United States by investigating any suspicious individuals. Soon many of the allegations surrounded Hollywood and the film industry. Screenwriters, producers, and directors were called to trial and questioned for Communist affiliations.1 These people were blacklisted from the film industry and it destroyed many of their careers. Blacklisting is an example of censorship around the media, the fear of communism in the United States, and an attempt to stand up for basic civil rights. The Hollywood Blacklists were heavily influenced by the “red scare”, and had negative lasting effects on the American motion-picture industry. When World War II ended in 1945 the violent war between the countries was over, but another kind of war began. The two major world powers, America and Russia, were in constant competition with one another for wealth, political power, technological advancements, and dominance among the nations. The basis of this competition came from the ideological 1 History.com Staff. "Hollywood Ten." History.com. 2009. Accessed April 19, 2018. -

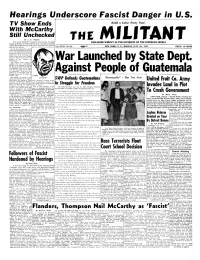

Fascist Danger in U.S

Hearings Underscore Fascist Danger in U.S. ------------------------------------------- ® --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- TV Show Ends Build a Labor Party Now! With McCarthy Still Unchecked By L. P. Wheeler The Army-McCarthy hearings closed June 17 after piling up 36 days of solid evidence that a fascist movement called McCarthyism has sunk roots deep into the govern ment and the military. For 36 days McCarthy paraded before some 20,000,000 TV viewers as the self-appointed custodian of America’s security. No one chal lenged him when he turned the Senate caucus room into a fascist forum to lecture with charts and pointer on the “menace of Communism.” War Launched by State Dept. This ghastly farce seems in credible. Yet the “anti-<McCar- thyites’’ in the hearing sat before the Wisconsin Senator and nodded in agreement while he hit them over the head with the “menace of Communism.” And then they blinked as if astonished when he Against People of Guatemala brought down his “21 years of treason” club. The charge of treason is the M cCa r t h y “Eventually” - But Not Now ready-made formula of the Amer SWP Defends Guatemalans ican fascists for putting a “save many unionists, minority people United Fruit Co. -

British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964 William Styles Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge September 2016 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy William Styles British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964 This thesis is concerned with an analysis of British governmental attitudes and responses to communism in the United Kingdom during the early years of the Cold War, from the election of the Attlee government in July 1945 up until the election of the Wilson government in October 1964. Until recently the topic has been difficult to assess accurately, due to the scarcity of available original source material. However, as a result of multiple declassifications of both Cabinet Office and Security Service files over the past five years it is now possible to analyse the subject in greater depth and detail than had been previously feasible. The work is predominantly concerned with four key areas: firstly, why domestic communism continued to be viewed as a significant threat by successive governments – even despite both the ideology’s relatively limited popular support amongst the general public and Whitehall’s realisation that the Communist Party of Great Britain presented little by way of a direct challenge to British political stability. Secondly, how Whitehall’s understanding of the nature and severity of the threat posed by British communism developed between the late 1940s and early ‘60s, from a problem considered mainly of importance only to civil service security practices to one which directly impacted upon the conduct of educational policy and labour relations. -

Lorne Bair :: Catalog 21

LORNE BAIR :: CATALOG 21 1 Lorne Bair Rare Books, ABAA PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 2621 Daniel Terrace Winchester, Virginia USA 22601 (540) 665-0855 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lornebair.com TERMS All items are offered subject to prior sale. Unless prior arrangements have been made, payment is expected with order and may be made by check, money order, credit card (Visa, MasterCard, Discover, American Express), or direct transfer of funds (wire transfer or Paypal). Institutions may be billed. Returns will be accepted for any reason within ten days of receipt. ALL ITEMS are guaranteed to be as described. Any restorations, sophistications, or alterations have been noted. Autograph and manuscript material is guaranteed without conditions or restrictions, and may be returned at any time if shown not to be authentic. DOMESTIC SHIPPING is by USPS Priority Mail at the rate of $9.50 for the first item and $3 for each additional item. Overseas shipping will vary depending upon destination and weight; quotations can be supplied. Alternative carriers may be arranged. WE ARE MEMBERS of the ABAA (Antiquarian Bookseller’s Association of America) and ILAB (International League of Antiquarian Book- sellers) and adhere to those organizations’ standards of professionalism and ethics. PART ONE African American History & Literature ITEMS 1-54 PART TWO Radical, Social, & Proletarian Literature ITEMS 55-92 PART THREE Graphics, Posters & Original Art ITEMS 93-150 PART FOUR Social Movements & Radical History ITEMS 151-194 2 PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 1. CUNARD, Nancy (ed.) Negro Anthology Made by Nancy Cunard 1931-1933. London: Nancy Cunard at Wishart & Co., 1934. -

Michael Gold & Dalton Trumbo on Spartacus, Blacklist Hollywood

LH 19_1 FInal.qxp_Left History 19.1.qxd 2015-08-28 4:01 PM Page 57 Michael Gold & Dalton Trumbo on Spartacus, Blacklist Hollywood, Howard Fast, and the Demise of American Communism 1 Henry I. MacAdam, DeVry University Howard Fast is in town, helping them carpenter a six-million dollar production of his Spartacus . It is to be one of those super-duper Cecil deMille epics, all swollen up with cos - tumes and the genuine furniture, with the slave revolution far in the background and a love tri - angle bigger than the Empire State Building huge in the foreground . Michael Gold, 30 May 1959 —— Mike Gold has made savage comments about a book he clearly knows nothing about. Then he has announced, in advance of seeing it, precisely what sort of film will be made from the book. He knows nothing about the book, nothing about the film, nothing about the screenplay or who wrote it, nothing about [how] the book was purchased . Dalton Trumbo, 2 June 1959 Introduction Of the three tumultuous years (1958-1960) needed to transform Howard Fast’s novel Spartacus into the film of the same name, 1959 was the most problematic. From the start of production in late January until the end of all but re-shoots by late December, the project itself, the careers of its creators and financiers, and the studio that sponsored it were in jeopardy a half-dozen times. Blacklist Hollywood was a scary place to make a film based on a self-published novel by a “Commie author” (Fast), and a script by a “Commie screenwriter” (Trumbo). -

Military Institutions and Activities, 1850-1980

LOS ANGELES CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT Guidelines for Evaluating Resources Associated with Military Institutions and Activities, 1850-1980 Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources November 2019 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Guidelines for Evaluating Resources Associated with Military Institutions and Activities TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 1 CONTRIBUTORS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 Related Contexts and Evaluation Considerations 1 Other Sources for Military Historic Contexts 3 MILITARY INSTITUTIONS AND ACTIVITIES HISTORIC CONTEXT 3 Historical Overview 3 Los Angeles: Mexican Era Settlement to the Civil War 3 Los Angeles Harbor and Coastal Defense Fortifications 4 The Defense Industry in Los Angeles: From World War I to the Cold War 5 World War II and Japanese Forced Removal and Incarceration 8 Recruitment Stations and Military/Veterans Support Services 16 Hollywood: 1930s to the Cold War Era 18 ELIGIBILITY STANDARDS FOR AIR RAID SIRENS 20 ATTACHMENT A: FALLOUT SHELTER LOCATIONS IN LOS ANGELES 1 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Guidelines for Evaluating Resources Associated with Military Institutions and Activities PREFACE These “Guidelines for Evaluating Resources Associated with Military Institutions and Activities” (Guidelines) were developed based on several factors. First, the majority of the themes and property types significant in military history in Los Angeles are covered under other contexts and themes of the citywide historic context statement as indicated in the “Introduction” below. Second, many of the city’s military resources are already designated City Historic-Cultural Monuments and/or are listed in the National Register.1 Finally, with the exception of air raid sirens, a small number of military-related resources were identified as part of SurveyLA and, as such, did not merit development of full narrative themes and eligibility standards. -

The Inventory of the Albert Maltz Collection #150

The Inventory of the Albert Maltz Collection #150 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Albert Maltz Manuscripts Box 1 1.) This Gun for Hire (1942) by Albert Maltz & Wo R. Burnett Movie script, dated October 5, 19/41. Typescript, carbon, holograph corrections, 150p. a9x 1 2.) "Husband and Wife" Short story s·econd draft, typescript with holograph corrections, 44P• Final draft, typescript, heavily corrected, 33p. / C/·. \..c. Box 1 J.) The Underground Stream (1940) Novel 11 Final draft with ms. changes" Typescript, carbon, holograph corrections and additions, 373p. '"' Maltz, Albert - Addenda Box:-:- 2 Folder "Material from the magazine 1F.quality1 published in New York, 1939-4011 11 holograph articles Folder "Anonymous Writings and Ghost Writings" 6 articles: 5 holograph, 1 typed Folder "Miscellaneous Non-Fiction Pieces" 17 articles: 13 holograph, 4 typed. Folder "Public lectures and Addresses" 7 articles: 5 holograph, 1 mimeo, l typed Folder "Short Stories" Season of Celebration Notes and discards. Holograph. Sunday Morning .Q!l 25th Street First notes. Holograph. Happiest Man Q!l Earth Notes and discards, holograph. Typescript of one drafto Way Things Are Notes for first draft, holograph. Discards from first and second version, holograph. Notes for revision, holograph, Second draft typescript with holograph corrections. Final version type8cript, last 2 rages missing. (Each folder contains typed list by.Albert Maltz identifying articles and giving number of pages of each piece.) Mi.ltz, Albert Addenda, October., 1967 SCBEENPLAY .-- . THE BOBE . A. Second draft of the screenplay, typed script with holograph changes ·on ~bi~type~cent of the pages. :.~2S pages. · .· ::,;:~:: ·<·: i; l · ;' . • • ;.:• B. Third' (final) draf.t, mimeographed ·224 pages. -

The Ideology of the John Birch Society

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1966 The Ideology of the John Birch Society Max P. Peterson Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Peterson, Max P., "The Ideology of the John Birch Society" (1966). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7982. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7982 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THEIDEOLOGY OFTHE JOHN BIRCH SOCIETY by Y1ax P. Peterson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTEROF SCIENCE in Political Science Approved: Major Professor Head of Department Dean of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 1966 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my appreciation to Dr. Milton C. Abrams for the many hours of consultation and direction he provided throughout this study. To Dr. M. Judd Harmon, I express thanks, not only for his constructive criticism on this work, but for the constant challenge he offers as a teacher. A very special thanks is given my wife, Karen, for her countless hours of typing, but first and foremost for the encouragement, u nderstanding, and devotion that she has given me throu ghout my graduate studies. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapter I. The Background and Organization of the John Birch Society 4 The Beginning 4 The Symbol 7 The Founder 15 Plan of Action 21 Organizational Mechanics 27 Chapter II. -

The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA)

Recordings at Risk Sample Proposal (Fourth Call) Applicant: The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project: Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Portions of this successful proposal have been provided for the benefit of future Recordings at Risk applicants. Members of CLIR’s independent review panel were particularly impressed by these aspects of the proposal: • The broad scholarly and public appeal of the included filmmakers; • Well-articulated statements of significance and impact; • Strong letters of support from scholars; and, • A plan to interpret rights in a way to maximize access. Please direct any questions to program staff at [email protected] Application: 0000000148 Recordings at Risk Summary ID: 0000000148 Last submitted: Jun 28 2018 05:14 PM (EDT) Application Form Completed - Jun 28 2018 Form for "Application Form" Section 1: Project Summary Applicant Institution (Legal Name) The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley Applicant Institution (Colloquial Name) UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project Title (max. 50 words) Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Project Summary (max. 150 words) In conjunction with its world-renowned film exhibition program established in 1971, the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) began regularly recording guest speakers in its film theater in 1976. The first ten years of these recordings (1976-86) document what has become a hallmark of BAMPFA’s programming: in-person presentations by acclaimed directors, including luminaries of global cinema, groundbreaking independent filmmakers, documentarians, avant-garde artists, and leaders in academic and popular film criticism. -

California Un-American Activities Committees Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft9p3007qg No online items Inventory of the California Un-American Activities Committees Records Processed by Archives Staff California State Archives 1020 "O" Street Sacramento, California 95814 Phone: (916) 653-2246 Fax: (916) 653-7363 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.sos.ca.gov/archives/ © 2000 California Secretary of State. All rights reserved. Inventory of the California 93-04-12; 93-04-16 1 Un-American Activities Committees Records Inventory of the California Un-American Activities Committees Records Collection number: 93-04-12; 93-04-16 California State Archives Office of the Secretary of State Sacramento, California Processed by: Archives Staff Date Completed: March 2000; Revised August 2014 Encoded by: Jessica Knox © 2000 California Secretary of State. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: California Un-American Activities Committees Records Dates: 1935-1971 Collection number: 93-04-12; 93-04-16 Creator: Senate Fact-Finding Subcommittee on Un-American Activities, 1961-1971;Senate Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities, 1947-1960;Joint Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities in California, 1941-1947;Assembly Relief Investigating Committee on Subversive Activities, 1940-1941 Collection Size: 48 cubic feet and 13 boxes Repository: California State Archives Sacramento, California Abstract: The California Un-American Activities Committees (CUAC) files (identification numbers 93-04-12 and 93-04-16) span the period 1935-1971 and consist of eighty cubic feet. The files document legislative investigations of labor unions, universities and colleges, public employees, liberal churches, and the Hollywood film industry. Later the committee shifted focus and concentrated on investigating communist influences in America, racial unrest, street violence, anti-war rallies, and campus protests. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: from the BELLY of the HUAC: the RED PROBES of HOLLYWOOD, 1947-1952 Jack D. Meeks, Doctor of Philos

ABSTRACT Title of Document: FROM THE BELLY OF THE HUAC: THE RED PROBES OF HOLLYWOOD, 1947-1952 Jack D. Meeks, Doctor of Philosophy, 2009 Directed By: Dr. Maurine Beasley, Journalism The House Un-American Activities Committee, popularly known as the HUAC, conducted two investigations of the movie industry, in 1947 and again in 1951-1952. The goal was to determine the extent of communist infiltration in Hollywood and whether communist propaganda had made it into American movies. The spotlight that the HUAC shone on Tinsel Town led to the blacklisting of approximately 300 Hollywood professionals. This, along with the HUAC’s insistence that witnesses testifying under oath identify others that they knew to be communists, contributed to the Committee’s notoriety. Until now, historians have concentrated on offering accounts of the HUAC’s practice of naming names, its scrutiny of movies for propaganda, and its intervention in Hollywood union disputes. The HUAC’s sealed files were first opened to scholars in 2001. This study is the first to draw extensively on these newly available documents in an effort to reevaluate the HUAC’s Hollywood probes. This study assesses four areas in which the new evidence indicates significant, fresh findings. First, a detailed analysis of the Committee’s investigatory methods reveals that most of the HUAC’s information came from a careful, on-going analysis of the communist press, rather than techniques such as surveillance, wiretaps and other cloak and dagger activities. Second, the evidence shows the crucial role played by two brothers, both German communists living as refugees in America during World War II, in motivating the Committee to launch its first Hollywood probe. -

Scoping out the International Spy Museum

Acad. Quest. DOI 10.1007/s12129-010-9171-1 ARTICLE Scoping Out the International Spy Museum Ronald Radosh # The Authors 2010 The International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C.—a private museum that opened in July 2002 at the cost of $40 million—is rated as one of the most visited and popular tourist destinations in our nation’s capital, despite stiff competition from the various public museums that are part of the Smithsonian. The popularity of the Spy Museum has a great deal to do with how espionage has been portrayed in the popular culture, especially in the movies. Indeed, the museum pays homage to cinema with its display of the first Aston Martin used by James Bond, when Agent 007 was played by Sean Connery in the films made during the JFK years. The Spy Museum’s board of directors includes Peter Earnest, a former CIA operative and the museum’s first chief executive; David Kahn, the analyst of cryptology; Gen. Oleg Kalugin, a former KGB agent; as well as R. James Woolsey, a former director of the CIA. Clearly, the board intends that in addition to the museum’s considerable entertainment value, its exhibits and texts convey a sense of the reality of the spy’s life and the historical context in which espionage agents operated. The day I toured the museum it was filled with high school students who stood at the various exhibits taking copious notes. It was obvious that before their visit the students had been told to see what the exhibits could teach them about topics discussed in either their history or social studies classes.