Analysis of Disaster Management Structures and Crossborder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P Orientation

Dentists p Kindergarten • Dr. Allroggen-Schultz Mühlenstiege 1, Telefon 0591 3897 Your child can go to a kindergarten. The fees • Dr. Bloms are paid for you by the Jugendamt.(Youth Am Treffpunkt 12. Telefon 0591 6919 Welfare Office). Visiting the kindergarten will • Dr. Börsting / Dr. Wortmeier help your child to quickly learn the German Gymnasialstraße 1, Telefon 0591 3055 language in games with other children. • Dr. Bröker The assistants at the SKM will help you to Mühlentorstraße 23, Telefon 0591 9154488 register your child. • Dr. Conen Poststraße 18, Telefon 0591 3231 p School • Dr. Dietzel p Welcome to Lingen! p Health Service Meppener Str. 124, Telefon 0591 96622452 School in Germany is compulsory for all We hope that you have arrived in good health, In Germany there are many doctors, for ex- • Dr. Goldschmidt children over 6 years of age. There are no fees. and we would like you to find your way in ample family physicians, childrens`physicians, Burgstraße 24, Telefon 0591 916550 At first a child must visit an elementary school Refugees welcome! Refugees Lingen with the help of this brochure. Certainly gyneacologists or dentists. Many doctors • Dr. Niemann / Dr. Haase close to your place of residence. After that you will have many questions regarding your have their own practice. Before you go to Kiesbergstr. 27, Telefon 0591 47146 you can choose between different secondary stay and are worried about your family left a doctor, you must make an appointment. • Dr. Hofschröer / Dr. Horrix schools. The assistants of the SKM will help behind and about living and working here. -

Die Euregiobahn

Stolberg-Mühlener Bahnhof – Stolberg-Altstadt 2021 > Fahrplan Stolberg Hbf – Eschweiler-St. Jöris – Alsdorf – Herzogenrath – Aachen – Stolberg Hbf Eschweiler-Talbahnhof – Langerwehe – Düren Bahnhof/Haltepunkt Montag – Freitag Mo – Do Fr/Sa Stolberg Hbf ab 5:11 6:12 7:12 8:12 18:12 19:12 20:12 21:12 22:12 23:12 23:12 usw. x Eschweiler-St. Jöris ab 5:18 6:19 7:19 8:19 18:19 19:19 20:19 21:19 22:19 23:19 23:19 alle Alsdorf-Poststraße ab 5:20 6:21 7:21 8:21 18:21 19:21 20:21 21:21 22:21 23:21 23:21 60 Alsdorf-Mariadorf ab 5:22 6:23 7:23 8:23 18:23 19:23 20:23 21:23 22:23 23:23 23:23 Minu- x Alsdorf-Kellersberg ab 5:24 6:25 7:25 8:25 18:25 19:25 20:25 21:25 22:25 23:25 23:25 ten Alsdorf-Annapark an 5:26 6:27 7:27 8:27 18:27 19:27 20:27 21:27 22:27 23:27 23:27 Alsdorf-Annapark ab 5:31 6:02 6:32 7:02 7:32 8:02 8:32 9:02 18:32 19:02 19:32 20:02 20:32 21:02 21:32 22:02 22:32 23:32 23:32 Alsdorf-Busch ab 5:33 6:04 6:34 7:04 7:34 8:04 8:34 9:04 18:34 19:04 19:34 20:04 20:34 21:04 21:34 22:04 22:34 23:34 23:34 Herzogenrath-A.-Schm.-Platz ab 5:35 6:06 6:36 7:06 7:36 8:06 8:36 9:06 18:36 19:06 19:36 20:06 20:36 21:06 21:36 22:06 22:36 23:36 23:36 Herzogenrath-Alt-Merkstein ab 5:38 6:09 6:39 7:09 7:39 8:09 8:39 9:09 18:39 19:09 19:39 20:09 20:39 21:09 21:39 22:09 22:39 23:39 23:39 Herzogenrath ab 5:44 6:14 6:44 7:14 7:44 8:14 8:44 9:14 18:44 19:14 19:44 20:14 20:45 21:14 21:44 22:14 22:44 23:43 23:43 Kohlscheid ab 5:49 6:19 6:49 7:19 7:49 8:19 8:49 9:19 18:49 19:19 19:49 20:19 20:50 21:19 21:49 22:19 22:49 23:49 23:49 Aachen West ab 5:55 6:25 6:55 -

Gewerbegebiet Simmerath - Erweiterung Ort: Simmerath

EXPOSÉ Gewerbegebiet Simmerath - Erweiterung Ort: Simmerath www.germansite.de Regional overview Municipal overview Detail view Parcel Area size 22,662 m² Availability Available area within short term (< 2 years) Divisible No 24h operation No © NRW.Global Business GmbH Page 1 of 4 09/27/2021 EXPOSÉ Gewerbegebiet Simmerath - Erweiterung Ort: Simmerath www.germansite.de Details on commercial zone Business park Simmerath - Expansion The increasing demand for further commercial spaces at the Simmerath location is being met by the designation of an extension area of approx. 13 ha. The current Simmerath industrial estate has existed since 1977 on an area of approx. 30 hectares. Approximately 120 companies have settled in the Simmerath industrial estate, whereby the commercial use is predominantly characterised by trade. Approximately 950 jobs are provided. Industrial tax multiplier 420.00 % Area type GE Links https://www.gistra.de Erreichbarkeit in 20 Minuten: 38.500 Einwohner Transport infrastructure Freeway A44 23.6 km Airport Maastricht Aachen 75.4 km Airport Liège (B) 79.9 km Port Liège (B) 65.7 km Port Am Godorfer Köln 67.5 km © NRW.Global Business GmbH Page 2 of 4 09/27/2021 EXPOSÉ Gewerbegebiet Simmerath - Erweiterung Ort: Simmerath www.germansite.de Information about Simmerath Simmerath represents an ambitious and modern community with 15,000 inhabitants. Located in the southern part of the Aachen region Simmerath is an interesting investment opportunity with excellent connection to the Netherlands, Belgium, Aachen and Cologne. Establishing, investing and expanding business in Simmerath is supported by governmental programs in order to strengthen industry structure. Majestic beech forests, gnarled oak trees and wild rivers: Experience pure nature in the Eifel National Park. -

Raesfeld-Route ( Ca.: 58 Km )

Raesfeld-Route ( ca.: 58 km ) Wegstreckenbeschreibung von M. Nieuwenhuizen Bocholt - Biemenhorst - Büngern - Krommert - Havelich - Marienthal - Erle - Raesfeld - Rhedebrügge - Krechting - Rhede - Bocholt Erklärungen: Pättken = kleine Feld-, Wald- und Wiesenwege unbefestigter Weg = die so angegebenen Wege sind gut mit dem Rad zu befahren P = Paddestoel oder Wegpilz Y = ANWB-Wegweiser auf Richtungsschild BT 639 Positionsbezeichnung der Radelpark-Wegweiser = Entfernung von - bis in Metern Start und Ziel: Aasee gegenüber dem Textilmuseum 0,00 km 1 vom Straßenschild „Gustav-Heinemann-Promenade“ geradeaus und sofort rechts ab Pflastersteinweg entlang dem Aasee in Richtung Seglerheim Bocholter Aasee Freizeit- u. Erholungsanlage mit Vogelschutzinsel. Die Gesamtfläche beträgt 74 ha, die sich in 32 ha Wasserfläche und 42 ha Grünzone aufteilt Wegweiser Radelpark Münsterland: BT 021 Wegweiser- und Strecken-Nummer finden Sie in der zugehörigen Karte BT 021 Rees 28 km, Bahnhof 0,8 km 132 253 Hinweis: links Königsmühlenweg BT 021 Winterswijk 20 km, Aalten 16 km 135 253 Hinweis: geradeaus BT 021 Borken 21 km, Rhede 6,5 km 132 135 zurück BT 021 Bocholt-Zentrum 1,3 km, LWL-Textilmuseum 160 m 0,16 km 2 über die Brücke hinweg und sofort links ab Pflastersteinweg 50 m 0,21 km 3 rechts ab roter Radweg entlang dem Aasee bis zum Stauwerk 140 m 0,35 km 4 geradeaus Radweg entlang dem Aasee - Brücke rechts Hinweis: rechts über die Brücke hinweg McDonald’s Restaurants Telefon: 02871 / 186241 Im Königsesch 5, 46397 Bocholt 500 m 0,85 km 5 geradeaus Radweg entlang dem Aasee - Brücke rechts in Richtung Im Königsesch 180 m 1,03 km 6 geradeaus roter Radweg entlang dem Aasee - Weg links Radelparkroute 200 m 1,23 km 7 durch die Unterführung (B 67) hinweg 240 m 1,47 km 8 geradeaus - Weg links Radelparkroute 10 m 1,48 km 9 - Ruhebänke - rechts ab über die Brücke hinweg geradeaus R 21, F 4 2 110 m 1,59 km 10 rechts ab über die Brücke (Pleystrang) hinweg 180 m 1,77 km 11 Ende des Weges links ab R 21, F 4 340 m 2,11 km 12 rechts ab Töppingsesch vorbei an den Kleingärten nach ca. -

Members and Sponsors

LOWER SAXONY NETWORK OF RENEWABLE RESOURCES MEMBERS AND SPONSORS The 3N registered association is a centre of expertise which has the objective of strengthening the various interest groups and stakeholders in Lower Saxony involved in the material and energetic uses of renewable resources and the bioeconomy, and supporting the transfer of knowledge and the move towards a sustainable economy. A number of innovative companies, communities and institutions are members and supporters of the 3N association and are involved in activities such as the production of raw materials, trading, processing, plant technology and the manufacturing of end products, as well as in the provision of advice, training and qualification courses. The members represent the diversity of the sustainable value creation chains in the non-food sector in Lower Saxony. 3 FOUNDING MEMBER The Lower Saxony Ministry for Food, Agriculture and Con- Contact details: sumer Protection exists since the founding of the state of Niedersächsches Ministerium für Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Verbraucherschutz Lower Saxony in 1946. Calenberger Str. 2 | 30169 Hannover The competences of the ministry are organized in four de- Contact: partments with the following emphases: Ref. 105.1 Nachwachsende Rohstoffe und Bioenergie Dept 1: Agriculture, EU farm policy (CAP), agricultural Dr. Gerd Höher | Theo Lührs environmental policy Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Dept 2: Consumer protection, animal health, animal Further information: www.ml.niedersachsen.de protection Dept 3: Spatial planning, regional development, support Dept 4: Administration, law, forests Activities falling under the general responsibility of the ministry are implemented by specific authorities as ‘direct’ state administration. -

Immer Weiter Volle Kraft Voraus!

Immer weiter volle Kraft voraus! TÄTIGKEITSBERICHT DES RATES DER STADT HAREN (EMS) 20162021 TÄTIGKEITSBERICHT 2021 02 Vorwort .............................................................................3 Wahlen ..................................................................... 4 Wohnen und Soziales ........................................... 26 Politischen Gremien ...........................................................5 Wohnen .............................................................................. 27 Ortschaften und Einwohner ........................................... 10 Stadtsanierung ..................................................................29 Ortsvorsteher und Ortsbeauftragte ................................ 11 Lebendige Ortschaften......................................................31 Soziales ...............................................................................34 Corona-Pandemie ..................................................12 Freiwillige Feuerwehren .................................................. 37 Freizeit, Kultur und Sport ...............................................38 Kitas, Schulen und Jugendarbeit ..........................14 Kindertagesstätten ............................................................15 Veranstaltungen .................................................... 42 Schulen ................................................................................17 Jugendarbeit ........................................................................19 Klima .....................................................................50 -

Die Bocholter Aa

ÜBER DIEÜBER REGION DIE REGION OVER DE OVERREGIO DE REGIO BESCHILDERUNGBESCHILDERUNG FIETSENBUSFIETSENBUS 1 1 58 km Radweg58 km inRadweg der Region in der Region Die Region rundDie umRegion die rundBocholter um dieAa Bocholterliegt eingebettet Aa liegt in eingebettet die in die De regio rondomDe deregio Bocholter rondom Aa de is Bocholter ingebed inAa het is ingebedMünsterlandse in het Münsterlandse Der RadwanderwegDer Radwanderweg „Bocholter Aa“ „Bocholter ist in beide Aa“ Rich- ist in beide Rich- Von Mai bis OktoberVon Mai pendeln bis Oktober sonn- pendeln und feiertags sonn- dieund sogenannten feiertags die sogenannten münsterländischemünsterländische Parklandschaft Parklandschaft und den Naturpark und den „Hohe Naturpark „Hohe parklandschapparklandschap en het natuurpark en het “Hohe natuurpark Mark”. Uitgestrekte “Hohe Mark”. velden Uitgestrekte velden tungen durchgehendtungen durchgehend beschildert. Da beschildert. er streckenweise Da er streckenweise Fietsenbusse Fietsenbussemit ihren Fahrradanhängern mit ihren Fahrradanhängern nahe der Fahrrad- nahe der Fahrrad- Mark“. Weite Feldfl uren wechseln sich mit kleinen Waldgebie- worden afgewisseld door kleine bosgebieden en schilderachtige auf der 100-Schlösser-Routeauf der 100-Schlösser-Route verläuft, gelten verläuft, auch die gelten auch die route: Die Linie R51 von Coesfeld über Velen bis Bocholt sowie 58 km fietsroute in de regio Mark“. Weite Feldfl uren wechseln sich mit kleinen Waldgebie- worden afgewisseld door kleine bosgebieden en schilderachtige route: Die Linie R51 von Coesfeld über Velen bis Bocholt sowie www.werbeagentur.ms 58 km fietsroute in de regio www.werbeagentur.ms ten und malerischenten und Flussauenmalerischen ab; Flussauen Cafés am ab;Wegesrand Cafés am und Wegesrand und rivierbeddingen;rivierbeddingen; in cafés langs dein cafésweg en langs in aantrekkelijke de weg en in aantrekkelijke stadjes stadjes bekannten Zwischenwegweiser.bekannten Zwischenwegweiser. -

ENERCON Magazine for Wind Energy 01/14

WINDBLATT ENERCON Magazine for wind energy 01/14 ENERCON installs E-115 prototype New two part blade concept passes practial test during installation at Lengerich site (Lower Saxony). ENERCON launches new blade test station Ultra modern testing facilities enables static and dynamic tests on rotor blades of up to 70m. ENERCON announces new WECs for strong wind sites E-82/2,3 MW and E-101/3 MW series also to be available for Wind Class I sites. 4 ENERCON News 21 ENERCON Fairs 23 ENERCON Adresses 12 18 Imprint Publisher: 14 New ENERCON wind energy converters ENERCON GmbH ENERCON announces E-82 and E-101 for strong wind sites. Dreekamp 5 D-26605 Aurich Tel. +49 (0) 49 41 927 0 Fax +49 (0) 49 41 927 109 www.enercon.de Politics Editorial office: Felix Rehwald 15 Interview with Matthias Groote, Member of the European Parliament Printed by: Chairmann of Committee on the Environment comments on EU energy policy. Beisner Druck GmbH & Co. KG, 8 Buchholz/Nordheide Copyright: 16 ENERCON Comment on EEG Reform All photos, illustrations, texts, images, WINDBLATT 01/14 graphic representations, insofar as this The Government's plans are excessive inflict a major blow on the onshore industry. is not expressly stated to the contrary, are the property of ENERCON GmbH and may not be reproduced, changed, transmitted or used otherwise without the prior written consent of Practice ENERCON GmbH. Cover Frequency: The WINDBLATT is published four 18 Replacing old machines times a year and is regularly enclosed 8 Installation of E-115 prototype to the «neue energie», magazine for Clean-up along coast: Near Neuharlingersiel ENERCON replaces 17 old turbines with 4 modern E-126. -

I Online Supplementary Data – Lötters, S. Et Al.: the Amphibian Pathogen Batrachochytrium Salamandrivorans in the Hotspot Of

Online Supplementary data – Lötters, S. et al.: The amphibian pathogen Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans in the hotspot of its European invasive range: past – present – future. – Salamandra, 56: 173–188 Supplementary document 1. Published site records (populations) of caudate species from Germany in which Bsal was detected until 2018. Data mostly summarized from Spitzen-van der Sluijs et al. (2016), Dalbeck et al. (2018), Lötters et al. (2018), Schulz et al. (2018) and Wagner et al. (2019a). In addition, new findings from the ongoing laboratory testing (especially quality assurance) of samples collected in same time frame were also included, so that some entries differ from those in the mentioned articles. Specimens tested positive for Bd/Bsal and negative for only Bd are indicated under remarks. Legend: † = dead specimen(s); + = ‘low’ infection load (1–10 GE); ++ = ‘medium’ infection load (> 10–100 GE); +++ = ‘high’ infection load (> 100 GE); CI = credible interval per year. Site District Coordinates Species Year N samples N samples Infection Prevalence 95% Remarks (latitude, tested Bsal- loads per year Bayesian longitude) positive CI Northern Eifel North Rhine-Westphalia, StädteRegion 50.578169, Fire salamander, Salamandra salamandra 2015 22 (of which 21 (of which 96% 79–99% mass mortality, 8 of 16 specimens Belgenbach Aachen 6.278448 16 †) 16 †) had Bd/Bsal co-infections Fire salamander, Salamandra salamandra 2017 12 larvae 0 0 0% 0–26% North Rhine-Westphalia, StädteRegion 50.746724, Northern crested newt, Triturus cristatus 2015 2 -

Wir Stellen Uns Vor

Wir stellen uns vor. Träger: Caritasverband für das Dekanat Bocholt e. V. WWW.BUENGERN-TECHNIK.DE Standorte der Werkstatt für Menschen mit Behinderungen Hauptwerkstatt Rhede-Büngern Mit der Gründung der Werkstatt Büngern-Technik, in Trägerschaft des Caritasverbandes für das Dekanat Bocholt e. V. nahmen im Juni 1969 neunzehn Beschäftigte in der ehe maligen Schule in Bün- gern ihre Arbeit auf. Nach zahlreichen Erweiterungen stehen heute an diesem Standort 262 anerkannte Werkstattplätze für Menschen mit Behinderungen zur Verfügung. Standort Borken In Borken wurden 1981 die Räumlichkeiten einer Holzspiel- warenfabrik übernommen. Nach mehrmaligen An- und Umbauten stehen an diesem Standort nunmehr 136 anerkannte Werkstatt- plätze zur Verfügung. Standort Mussum Im Oktober 2004 wurde im Industriepark Schlavenhorst ein weiterer Standort der Büngern-Technik eröffnet. Durch eine Erwei- terung in 2012 stehen hier insgesamt 200 anerkannte Werkstatt- plätze für Menschen mit Behinderungen zur Verfügung. Standorte Rhede (integra Industrieservice) Im Industriegebiet Rhede stehen am Standort Voßkamp seit 1994 Arbeitsplätze für Menschen mit psychischen Behinderungen zur Verfügung. Durch eine Erweiterung des nahegelegenen zweiten Standortes am Binnenpaß können nun insgesamt 130 anerkannte Werkstattplätze für diesen Personenkreis angebo- ten werden. 2 Werkstatt für Menschen mit Behinderungen Wer wird in die Werkstatt aufgenommen? In die Werkstatt Büngern-Technik Deutsche Rentenversicherung, der werden Menschen mit einer geisti- Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe gen, körperlichen oder psychischen oder einer Berufsgenossenschaft. Behinderung aufgenommen. Voraus- Der hierfür erforderliche Antrag ist setzung für die Aufnahme ist eine in der Regel bei der Arbeitsagentur vom Facharzt (Neurologe/Psychiater) zu stellen. diagnostizierte wesentliche Behin- derung, die eine Tätigkeit auf dem Das Einzugsgebiet der Werkstatt allgemeinen Arbeitsmarkt, dauerhaft umfasst von West nach Ost oder vorübergehend, ausschließt. -

ROSEN Group: Location Map Lingen

ROSEN GROUP LOCATION LINGEN --- ROSEN Technology and Research Center GmbH Emden Lingen Center Am Seitenkanal 8 Visitor Entrance B 213 49811 Lingen (Ems) Edisonstraße 2 Lohne B 213 Exit Germany 49811 Lingen (Ems) Industriepark Süd Edisonstraße 2 Germany B 70 A31 Phone +49-591-9136-0 Poller Sand Rheine Fax +49-591-9136-121 Am Seitenkanal Düsseldorf [email protected] ROFRESH ROSEN Technology & ROKIDS Research Center ROBIGS ROSEN Germany ROSEN Germany GmbH A ROYOUTH Am Seitenkanal 8 Visitor Entrance 49811 Lingen (Ems) Edisonstraße 2 FROM AIRPORT DÜSSELDORF (MAP C) Germany 49811 Lingen (Ems) • Depart Airport – follow blue road sign for highway Germany • Turn to A44 – direction Hattingen/Bochum Phone +49-591-9136-0 • Change to A52 – direction Essen Fax +49-591-9136-121 • Switch to A3 – direction Duisburg/Oberhausen [email protected] • Stay on A2 – direction Recklinghausen/Dortmund • Turn right to A31 – direction Gronau/Emden ROCARE GmbH ROSEN Catering GmbH • Leave A31 at Lingen (Map A) Am Seitenkanal 8 Am Seitenkanal 8 • Turn right to B213 (ring road of Lingen) – direction Lingen 49811 Lingen (Ems) 49811 Lingen (Ems) • Turn right to B70 – direction Rheine Germany Germany • For ‘Am Seitenkanal 8’ take exit ‘Industriepark Süd’ at the • traffic light (‘Poller Sand’) (Map A) Phone +49-591-9136 – 0 Phone +49-591-9136-150 • Turn left to ‘Am Seitenkanal’, ‘Am Seitenkanal 8’ – ROSEN Fax +49-591-9136 – 121 Fax +49-591-9136-130 • For ‘Edisonstraße 2’, pass first traffic light, turn right after rosen-lingen@ [email protected] • the second traffic light to ‘Edisonstraße’ (Map A) – ROSEN. -

Obere Ems II

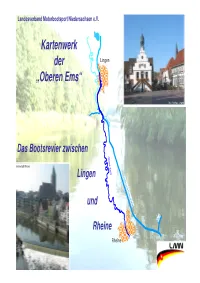

Landesverband Motorbootsport Niedersachsen e.V. Kartenwerk der Lingen „Oberen Ems“ hist. Rathaus Lingen Das Bootsrevier zwischen Innenstadt Rheine Lingen und Rheine Rheine 2 Vorwort Kartenübersicht Die „Obere Ems“ ist ein einzigartiges Bootsrevier am Rande des Dortmund- Ems- Kanals, eine historische Handels-Wasserstraße, die die Stadt Rheine mit dem bundesdeutschen Wasserstraßennetz und letztlich mit der Nordsee verbindet. Die beschauliche Emslandschaft bildet eine Einheit von Wasser, Wiesen und Wäl- dern und ist Heimat einer mannigfaltigen Tier- und Pflanzenwelt. Erholungssuchende genießen im Einklang mit der Natur dieses Paradies der Ruhe. Lingen Die befahrbare „Obere Ems“ beginnt in der Stadt Rheine bei Km 45 und endet bei Km 82,5 bei der Schleuse Gleesen (DEK Km 138). Auf dieser Strecke werden vier Schleusen, drei Häfen von Boots- und Yachtclubs sowie einige Anlegestellen passiert, bevor man letztlich die Anlegestellen der Stadt Rheine erreicht. Der Pegel und die Regeln der Flussfahrt (Seite 3) bestimmen hier die Planung der Reise. Sollte der Kurs einmal nicht optimal gewählt sein, der Grund ist im Regelfall sandig und verzeiht solche Pannen. Die Orte Emsbüren und Salzbergen befinden sich unweit des Flusses und auch die Stadt Rheine lädt mit ihrem Stadtzentrum, beidseitig des Flusses, zu einem Besuch ein. Ein besonderer Anlaufpunkt ist das Kloster Bentlage mit seinen Salinenanlagen und vielem anderen mehr. Wer das Stadtzentrum Rheine und den Freizeitbereich Bentlage besuchen möchte, jedoch auf die Fahrt über die Obere Ems verzichten muss, hat zwei Möglichkeiten: Er macht in Salzbergen fest, und benutzt die nur wenige Gehminuten entfernte Zugverbindung nach Rheine (6 Minuten Fahrzeit) oder bleibt auf dem DEK Km 117,8 (Liegestelle im Oberwasser der Schleuse Altenrheine, Restaurant, Bäcker u.