An Exploration of Rights Management Technologies Used in the Music Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mac OS X Includes Built-In FTP Support, Easily Controlled Within a fifteen-Mile Drive of One-Third of the US Population

Cover 8.12 / December 2002 ATPM Volume 8, Number 12 About This Particular Macintosh: About the personal computing experience™ ATPM 8.12 / December 2002 1 Cover Cover Art Robert Madill Copyright © 2002 by Grant Osborne1 Belinda Wagner We need new cover art each month. Write to us!2 Edward Goss Tom Iov ino Editorial Staff Daniel Chvatik Publisher/Editor-in-Chief Michael Tsai Contributors Managing Editor Vacant Associate Editor/Reviews Paul Fatula Eric Blair Copy Editors Raena Armitage Ya n i v E i d e l s t e i n Johann Campbell Paul Fatula Ellyn Ritterskamp Mike Flanagan Brooke Smith Matt Johnson Vacant Matthew Glidden Web E ditor Lee Bennett Chris Lawson Publicity Manager Vacant Robert Paul Leitao Webmaster Michael Tsai Robert C. Lewis Beta Testers The Staff Kirk McElhearn Grant Osborne Contributing Editors Ellyn Ritterskamp Sylvester Roque How To Ken Gruberman Charles Ross Charles Ross Gregory Tetrault Vacant Michael Tsai Interviews Vacant David Zatz Legacy Corner Chris Lawson Macintosh users like you Music David Ozab Networking Matthew Glidden Subscriptions Opinion Ellyn Ritterskamp Sign up for free subscriptions using the Mike Shields Web form3 or by e-mail4. Vacant Reviews Eric Blair Where to Find ATPM Kirk McElhearn Online and downloadable issues are Brooke Smith available at http://www.atpm.com. Gregory Tetrault Christopher Turner Chinese translations are available Vacant at http://www.maczin.com. Shareware Robert C. Lewis Technic a l Evan Trent ATPM is a product of ATPM, Inc. Welcome Robert Paul Leitao © 1995–2002, All Rights Reserved Kim Peacock ISSN: 1093-2909 Artwork & Design Production Tools Graphics Director Grant Osborne Acrobat Graphic Design Consultant Jamal Ghandour AppleScript Layout and Design Michael Tsai BBEdit Cartoonist Matt Johnson CVL Blue Apple Icon Designs Mark Robinson CVS Other Art RD Novo DropDMG FileMaker Pro Emeritus FrameMaker+SGML RD Novo iCab 1. -

What's the Download® Music Survival Guide

WHAT’S THE DOWNLOAD® MUSIC SURVIVAL GUIDE Written by: The WTD Interactive Advisory Board Inspired by: Thousands of perspectives from two years of work Dedicated to: Anyone who loves music and wants it to survive *A special thank you to Honorary Board Members Chris Brown, Sway Calloway, Kelly Clarkson, Common, Earth Wind & Fire, Eric Garland, Shirley Halperin, JD Natasha, Mark McGrath, and Kanye West for sharing your time and your minds. Published Oct. 19, 2006 What’s The Download® Interactive Advisory Board: WHO WE ARE Based on research demonstrating the need for a serious examination of the issues facing the music industry in the wake of the rise of illegal downloading, in 2005 The Recording Academy® formed the What’s The Download Interactive Advisory Board (WTDIAB) as part of What’s The Download, a public education campaign created in 2004 that recognizes the lack of dialogue between the music industry and music fans. We are comprised of 12 young adults who were selected from hundreds of applicants by The Recording Academy through a process which consisted of an essay, video application and telephone interview. We come from all over the country, have diverse tastes in music and are joined by Honorary Board Members that include high-profile music creators and industry veterans. Since the launch of our Board at the 47th Annual GRAMMY® Awards, we have been dedicated to discussing issues and finding solutions to the current challenges in the music industry surrounding the digital delivery of music. We have spent the last two years researching these issues and gathering thousands of opinions on issues such as piracy, access to digital music, and file-sharing. -

Information Disclosure Mechanism for Technological Protection Measures in China

Journal of Intellectual Property Rights Vol 17, November 2012, pp 532-538 Information Disclosure Mechanism for Technological Protection Measures in China Lili Zhao† Center for China Information Security Law, Xi’an Jiao tong University, Shaanxi Xi’an, P R China 710 049 Received 12 February 2012, revised 21 May 2012 With increasing cases of digital works being copied and pirated, technological protection measures have been greatly favoured by copyright owners for protecting the intellectual property in their digital works, while ensuring that these works can be used and disseminated. However, when any copyright owner or supplier fails to disclose the information of technological protection measures appropriately or effectively, damages such as privacy violations, security breaches and unfair competition may be caused to the public. Therefore, it is necessary to establish an information disclosure mechanism for technological protection measures, make the labeling obligation with regard to technological protection measures by copyright owners apparent and warning to security risks obligatory by legislation; effectively guarding against information security threats from the technological protection measures. Keywords: Technological protection measures, TPM, information disclosure, label and warning The advance of digital technologies make many information security, it is necessary to integrate such acts things become possible, including the copy and in a standardized, normalized and legal manner. dissemination of commercially valuable digital works Therefore, to further prevent copyright owners from through global digital network. Particularly, among using insecure or untested software, protect information the copyright owners of entertainment industry, security and prohibit the abuse of TPMs; disclosure technological protection measures (TPMs) have been obligations should be established for the right holders of regarded as a necessary creation to help digital works TPMs in the form of legislation. -

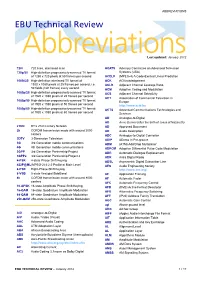

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review AbbreviationsLast updated: January 2012 720i 720 lines, interlaced scan ACATS Advisory Committee on Advanced Television 720p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Systems (USA) of 1280 x 720 pixels at 50 frames per second ACELP (MPEG-4) A Code-Excited Linear Prediction 1080i/25 High-definition interlaced TV format of ACK ACKnowledgement 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second, i.e. ACLR Adjacent Channel Leakage Ratio 50 fields (half frames) every second ACM Adaptive Coding and Modulation 1080p/25 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACS Adjacent Channel Selectivity of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second ACT Association of Commercial Television in 1080p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Europe of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 50 frames per second http://www.acte.be 1080p/60 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACTS Advanced Communications Technologies and of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 60 frames per second Services AD Analogue-to-Digital AD Anno Domini (after the birth of Jesus of Nazareth) 21CN BT’s 21st Century Network AD Approved Document 2k COFDM transmission mode with around 2000 AD Audio Description carriers ADC Analogue-to-Digital Converter 3DTV 3-Dimension Television ADIP ADress In Pre-groove 3G 3rd Generation mobile communications ADM (ATM) Add/Drop Multiplexer 4G 4th Generation mobile communications ADPCM Adaptive Differential Pulse Code Modulation 3GPP 3rd Generation Partnership Project ADR Automatic Dialogue Replacement 3GPP2 3rd Generation Partnership -

Intellectual Property Part 2 Pornography

Intellectual Property Part 2 Pornography By Jeremy Parmenter What is pornography Pornography is the explicit portrayal of sexual subject matter Can be found as books, magazines, videos The web has images, tube sites, and pay sites scattered with porn Statistics 12% of total websites are pornography websites 25% of total daily search engine requests are pornographic requests 42.7% of internet users who view pornography 34% internet users receive unwanted exposure to sexual material $4.9 billion in internet pornography sales 11 years old is the average age of first internet exposure to pornography Innovations ● Richard Gordon created an e-commerce start up in mid- 90s that was used on many sites, most notably selling Pamela Anderson/Tommey Lee sex tape ● Danni Ashe founded Danni's Hard Drive with one of the first streaming video without requiring a plug-in ● Adult content sites were one of the first to use traffic optimization by linking to similar sites ● Live chat during the early days of the web ● Pornographic companies were known to give away broadband devices to promote faster connections Negative Impacts ● Between 2001-2002 adult-oriented spam rose 450% ● Malware such as Trojans and video codecs occur most often on porn sites ● Domain hijacking, using fake documents and information to steal a site ● Pop-ups preventing users from leaving the site or infecting their computer ● Browser hijacking adware or spyware manipulating the browser to change home page or search engine to a bogus site, including pay-per-click adult site ● Accessibility -

Digital Grand Series

DIGITAL GRAND SERIES RG-3M/RG-3 RG-7-R KR117M-R KR115M-R/KR115-R KR111 HP109 Roland Corporation U.S. All specifications and appearances are subject to change without notice. 5100 S.Eastern Avenue P.O BOX 910921 All trademarks used in this catalog are the property of their respective companies. Los Angeles, CA 90091-0921 Phone: (323) 890.3700 Fax: (323) 890.3701 Visit us online at www.RolandUS.com Printed in Japan Sep. '07 RAM-4229 E-3 GR-UPR-P The Pinnacle of Elegance and Quality … Roland’s Digital Grand Series Elegance, expression, and emotion characterize the Roland Digital Grand piano experience. From casual home-entertainment gatherings to public performances, Roland instruments represent the pinnacle in quality design, sound, touch, expressiveness, and functionality. Roland grand pianos cover a broad universe. Treat your eyes and ears to Roland — the very best of the best. RG-7-R Authentic weighted touch that’s a dream to play Elegant, High-Gloss Cabinetry, Gorgeous Piano Sound, First-Class Quality Inside and Out DESIGN TOUCH The stately presence and Choose a design that suits PHA II Keyboard that consists of base- and surface-material layers, and elegant ambience of a grand piano your purpose and space (Progressive Hammer Action II) they’re designed to absorb moisture, ensuring a secure, slip-proof feel that your fingers will love. Our piano cabinetry is carefully polished by expertly skilled From space saving to stately, Roland’s digital piano lineup The RG and KR-Grand series*1 share the PHA II keyboard in *1 KR111, RG-7-PW, RG-7-PM, and HP109 are not available with Ivory Feel Keyboard. -

The California Supreme Court Holds a Preliminary Injunction Prohibiting

Volume 11 Issue 2 Article 4 2004 Website Operators and Misappropriators Beware - The California Supreme Court Holds a Preliminary Injunction Prohibiting Internet Posting of DVD Decryption Source Code Does Not Violate the First Amendment in DVD Copy Control Association, Inc. v. Bunner Nick Washburn Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Nick Washburn, Website Operators and Misappropriators Beware - The California Supreme Court Holds a Preliminary Injunction Prohibiting Internet Posting of DVD Decryption Source Code Does Not Violate the First Amendment in DVD Copy Control Association, Inc. v. Bunner, 11 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 341 (2004). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol11/iss2/4 This Casenote is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Washburn: Website Operators and Misappropriators Beware - The California Su WEBSITE OPERATORS AND MISAPPROPRIATORS BEWARE! THE CALIFORNIA SUPREME COURT HOLDS A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION PROHIBITING INTERNET POSTING OF DVD DECRYPTION SOURCE CODE DOES NOT VIOLATE THE FIRST AMENDMENT IN DVD COPY CONTROL ASSOCIATION, INC. V BUNNER I. INTRODUCTION A. DVDs, CSS, and the Creation of the DVD CCA Digital versatile discs ("DVDs") are small discs capable of hold- ing enough information to display a full-length motion picture which can be played on a personal DVD player.' DVDs were cre- ated in the early 1990s to provide higher visual and audio quality in displaying motion pictures over then existing analog tapes. -

Mechanical Instruments and Phonography: the Recording Angel of Historiography”, Radical Musicology, No Prelo

Silva, João, “Mechanical instruments and phonography: The Recording Angel of historiography”, Radical Musicology, no prelo. Mechanical instruments and phonography: The Recording Angel of historiography This article strives to examine the established historical narrative concerning music recording. For that purpose it will concentrate on the phonographic era of acoustic recording (from 1877 to the late 1920s), a period when several competing technologies for capturing and registering sound and music were being incorporated in everyday life. Moreover, it will analyse the significant chronological overlap of analogue and digital media and processes of recording, thus adding a layer of complexity to the current historical narratives regarding that activity. In order to address that set of events, this work will mainly recur to the work of both Walter Benjamin and Slavoj Žižek. Benjamin’s insight as an author that bore witness to and analysed the processes of commodification that were operating in the period in which this article concerns is essential in a discussion that focuses on aspects such as modernity, technology, and history. Furthermore, his work on history presents a space in which to address and critique the notion of historicism as an operation that attempts to impose a narrative continuity to the fragmentary categories of existence within modernity, a stance this article will develop when analysing the historiography of music and sound recording. The work of Žižek is especially insightful in tracing a distinction between historicism -

Copy Protection

Content Protection / DRM Content Protection / Digital Rights Management Douglas Dixon November 2006 Manifest Technology® LLC www.manifest-tech.com 11/2006 Copyright 2005-2006 Douglas Dixon, All Rights Reserved – www.manifest-tech.com Page 1 Content Protection / DRM Content Goes Digital Analog -> Digital for Content Owners • Digital Threat – No impediment to casual copying – Perfect digital copies – Instant copies – Worldwide distribution over Internet – And now High-Def content … • Digital Promise – Can protect – Encrypt content – Associate rights – Control usage 11/2006 Copyright 2005-2006 Douglas Dixon, All Rights Reserved – www.manifest-tech.com Page 2 1 Content Protection / DRM Conflict: Open vs. Controlled Managed Content • Avoid Morality: Applications & Technology – How DRM is impacting consumer use of media – Awareness, Implications • Consumers: “Bits want to be free” – Enjoy purchased content: Any time, anywhere, anyhow – Fair Use: Academic, educational, personal • Content owners: “Protect artist copyrights” – RIAA / MPAA : Rampant piracy (physical and electronic) – BSA: Software piracy, shareware – Inhibit indiscriminate casual copying: “Speed bump” • “Copy protection” -> “Content management” (DRM) 11/2006 Copyright 2005-2006 Douglas Dixon, All Rights Reserved – www.manifest-tech.com Page 3 Content Protection / DRM Content Protection / DRM How DRM is being applied • Consumer Scenarios: Impact of DRM – Music CD Playback on PC – Archive Digital Music – Play and Record DVDs – Record and Edit Personal Content • Industry Model: Content -

Where Is the Music? Au Id #: 1640352

WHERE IS THE MUSIC? AN ANALYSIS OF THE RECORDING INDUSTRY MAJOR LABELS ENDURING DIGITAL MEDIA TRANSFORMATION DANIEL GOODRICH AU ID #: 1640352 DECEMBER 10, 2007 DR. ROBERT EDGELL BUSINESS POLICY AND STRATEGY WHERE IS THE MUSIC? - 2 - GOODRICH HONORS CAPSTONE SUPPLEMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 THE MUSIC RECORDING INDUSTRY 4 HISTORY OF RECORDING FORMAT TECHNOLOGY 4 THE “MAJORS” 5 FALL OF CD SALES 9 IMPACT OF DIGITAL MUSIC 12 DIFFERING VIEWS ON DIGITAL RIGHTS MANAGEMENT 14 DRM APPLICATIONS 15 THOUGHTS ON MUSIC 16 OTHER IDEAS 18 TAKING THE MUSIC INTO THEIR OWN HANDS 19 INDUSTRY ANALYSIS 22 VALUE CHAIN ANALYSIS 22 RECOMMENDATIONS 23 CONCLUSION 25 APPENDICES 26 GRAPH 1 26 GRAPH 2 26 GRAPH 3 27 GRAPH 4 27 GRAPH 5 28 GRAPH 6 28 GRAPH 7 29 TABLE 1 30 TABLE 2 31 TABLE 3 32 WORKS CITED 33 WHERE IS THE MUSIC? - 3 - GOODRICH INTRODUCTION Some consider it a universal language that has no limitations. Some are born with a rhythm and grow alongside it. Some hear it in nature. Some devote their lives to studying it, others creating it and delivering it to the world. Some have it embedded within their souls and know that they could not be complete without it. For these individuals, music is the lifeblood of their being. Whether passionate about music, simply a fan, or even incapable of tolerating the sound of a drum, there is something unbelievable about music that seems to spark a change in people; it has the power to evoke every type of emotion. Those within the music recording industry understand this power, and continually search for the best possible and most profitable way to deliver this unique media to the world. -

Digital Rights Management

Journal of Intellectual Property Rights Vol 9, July 2004, pp 313-331 Digital Rights Management: An Integrated Secure Digital Content Distribution Technology P Ghatak, R C Tripathi, A K Chakravarti Department of Information Technology, Electronics Niketan, 6, CGO Complex, New Delhi-110 003 Received 5 December 2003 The ability to distribute copyrighted works in digital form through high capacity prere- corded disks (CD ROMs, DVDs etc.) and Internet-enabled transmissions have brought new challenges to the protections of such content from unauthorized copying and use. Technological advancements in this regard are reviewed. Despite the ease with which digital content owners can now transfer data, images, music, video and multimedia documents across the Internet, cur- rent technology does not let them protect their rights to the works, which has resulted into wide- spread music and video piracy. In fact, although the Internet permits widespread dissemination of digital content, the easy-to-copy nature of digital data limits content owners’ willingness to distribute their documents electronically. Digital Rights Management (DRM) technology is a key enabler for the distribution of digital content. DRM refers to protecting ownership/copyright of electronic content by restricting the extent of usage an authorized recipient is allowed in re- gard to that content. DRM technology has historically been viewed as the methodology for the protection of digital media copyrights. But DRM technology products can be leveraged to ad- dress much larger issues, including the control of rights and usage permissions of content and digital information. DRM presents the opportunity to package, price, distribute and sell content in many new ways that have never been possible before. -

MTO 20.1: Willey, Editing and Arrangement

Volume 20, Number 1, March 2014 Copyright © 2014 Society for Music Theory The Editing and Arrangement of Conlon Nancarrow’s Studies for Disklavier and Synthesizers Robert Willey NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.14.20.1/mto.14.20.1.willey.php KEYWORDS: Conlon Nancarrow, MIDI, synthesis, Disklavier ABSTRACT: Over the last three decades a number of approaches have been used to hear Conlon Nancarrow’s Studies for Player Piano in new settings. The musical information necessary to do this can be obtained from his published scores, the punching scores that reveal the planning behind the compositions, copies of the rolls, or the punched rolls themselves. The most direct method of extending the Studies is to convert them to digital format, because of the similarities between the way notes are represented on a player piano roll and in MIDI. The process of editing and arranging Nancarrow’s Studies in the MIDI environment is explained, including how piano roll dynamics are converted into MIDI velocities, and other decisions that must be made in order to perform them in a particular environment: the Yamaha Disklavier with its accompanying GM sound module. While Nancarrow approved of multi-timbral synthesis, separating the voices of his Studies and assigning them unique timbres changes the listener’s experience of the “resultant,” Tenney’s term for the fusion of multiple voices into a single polyphonic texture. Received January 2014 1. Introduction [1.1] Conlon Nancarrow’s compositional output from 1948 until his death in 1997 was primarily for the two player pianos in his studio in Mexico City.