Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chitrakars in Naya: Emotion and the Ways of Remembrance

Words and Silences is the Digital Edition Journal of the International Oral History Association. It includes articles from a wide range of disciplines and is a means for the professional community to share projects and current trends of oral history from around the world. http://ioha.org Online ISSN 2222-4181 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA Words and Silences March 2018 “Oral History and Emotions” The Chitrakars in Naya: Emotion and the Ways of Remembrance Reeti Basu Centre for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India [email protected] Introduction The Patuas are a community of painters living in the eastern part of India, West Bengal. Patuas or Chitrakars have been practicing patachitra or patashilpa for centuries. Patachitra or patashilpa is a form of scroll painting. Their diverse repertoire includes tales from Hindu mythology, tribal folklore, as well as Islamic tradition. They paint their stories on long scrolls and sing, as the scroll is unrolled frame by frame. The community of Patuas is spread over many districts of pre-partitioned Bengal: Mursidabad, Bankura, South Twenty-four-Parganas etc (including present-day Bangladesh). Today there are only a few practicing Patuas. Most of them live in the Indian districts of Medinipur and Birbhum (West Bengal). Even in Medinipur, the Patuas are giving up their art and taking to carpentry and farming. The market for pats has shrunk and the income has declined. -

Appellate Side DAILY CAUSELIST for Friday the 29Th January 2021

Appellate Jurisdiction Daily Supplementary List Of Cases For Hearing On Friday, 29th of January, 2021 CONTENT SL COURT PAGE BENCHES TIME NO. ROOM NO. NO. HON'BLE CHIEF JUSTICE THOTTATHIL B. 1 On 29-01-2021 1 RADHAKRISHNAN 1 DB -I At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 37 On 29-01-2021 2 12 HON'BLE JUSTICE MD. NIZAMUDDIN DB - III At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 3 On 29-01-2021 3 13 HON'BLE JUSTICE MD. NIZAMUDDIN DB - III At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE HARISH TANDON 2 On 29-01-2021 4 15 HON'BLE JUSTICE BIBEK CHAUDHURI DB At 02:00 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE HARISH TANDON 2 On 29-01-2021 5 16 HON'BLE JUSTICE KAUSIK CHANDA DB- IV At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 12 On 29-01-2021 6 27 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAVI KRISHAN KAPUR DB At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 12 On 29-01-2021 7 28 HON'BLE JUSTICE ANIRUDDHA ROY DB - V At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 11 On 29-01-2021 8 30 HON'BLE JUSTICE HIRANMAY BHATTACHARYYA DB - VI At 10:45 AM 11 On 29-01-2021 9 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 33 SB At 02:00 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY 28 On 29-01-2021 10 36 HON'BLE JUSTICE TIRTHANKAR GHOSH DB - VII At 10:45 AM 28 On 29-01-2021 11 HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY 49 SB - I At 03:00 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM SINHA 4 On 29-01-2021 12 51 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUVRA GHOSH DB - VIII At 10:45 AM 4 On 29-01-2021 13 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM SINHA 54 SB - II At 03:00 PM 6 On 29-01-2021 14 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE 58 SB At 10:45 AM 38 On 29-01-2021 15 HON'BLE JUSTICE ASHIS KUMAR CHAKRABORTY 66 SB - II At 10:45 AM 9 On 29-01-2021 16 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHIVAKANT PRASAD 67 SB - III At 10:45 AM 13 On 29-01-2021 17 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJASEKHAR MANTHA 70 SB - IV At 10:45 AM SL NO. -

Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education, Dinajpur ======S.S.C

BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, DINAJPUR =============== S.S.C. EXAMINATION- 2018 ============== PROBLEM LIST ================================== PAGE NO: 1 ZILLA : 50 - RANGPUR THANA : 5001 - RANGPUR SADAR ============================================================================= SL. JSC ROL PASS YEAR NAME/SCHOOL | PROBLEM ============================================================================= 1 | 123027 | 2015 MD. SAKIB HOSSAIN | INVALID JSC INFORMATION | DIN | 1136-AL-MADINA INSTITUTE | ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 | 386835 | 2015 SHAFAET HOSSAIN | INVALID JSC INFORMATION | DIN | 1136-AL-MADINA INSTITUTE | ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 | 501068 | 2015 FARDOSHY AKTHER | Dup From SCH-8948 | DIN | 1136-AL-MADINA INSTITUTE | DR. AFTAB UDDIN GIRLS' H ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 | 502226 | 2015 MOST. KHUSBO JAHAN AKTAR TINNI | Dup From SCH-5318 | DIN | 1136-AL-MADINA INSTITUTE | BIAM MODEL SCHOOL AND CO ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 | 504877 | 2015 MD. MEHEDI HASSAN | Dup From SCH-5251 | DIN | 1136-AL-MADINA INSTITUTE | KERAMATIA HIGH SCHOOL ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 | 158209 | 2015 ATIKA AKTER | Dup From SCH-5261 | DHK | 1147-BEGUM JOBEDA AZIZON GIRLS' HIGH | MARIUM NESSA GIRLS' HIGH ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 -

Annotated Bibliography of Studies on Muslims in India

Studies on Muslims in India An Annotated Bibliography With Focus on Muslims in Andhra Pradesh (Volume: ) EMPLOYMENT AND RESERVATIONS FOR MUSLIMS By Dr.P.H.MOHAMMAD AND Dr. S. LAXMAN RAO Supervised by Dr.Masood Ali Khan and Dr.Mazher Hussain CONFEDERATION OF VOLUNTARY ASSOCIATIONS (COVA) Hyderabad (A. P.), India 2003 Index Foreword Preface Introduction Employment Status of Muslims: All India Level 1. Mushirul Hasan (2003) In Search of Integration and Identity – Indian Muslims Since Independence. Economic and Political Weekly (Special Number) Volume XXXVIII, Nos. 45, 46 and 47, November, 1988. 2. Saxena, N.C., “Public Employment and Educational Backwardness Among Muslims in India”, Man and Development, December 1983 (Vol. V, No 4). 3. “Employment: Statistics of Muslims under Central Government, 1981,” Muslim India, January, 1986 (Source: Gopal Singh Panel Report on Minorities, Vol. II). 4. “Government of India: Statistics Relating to Senior Officers up to Joint-Secretary Level,” Muslim India, November, 1992. 5. “Muslim Judges of High Courts (As on 01.01.1992),” Muslim India, July 1992. 6. “Government Scheme of Pre-Examination Coaching for Candidates for Various Examination/Courses,” Muslim India, February 1992. 7. National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO), Department of Statistics, Government of India, Employment and Unemployment Situation Among Religious Groups in India: 1993-94 (Fifth Quinquennial Survey, NSS 50th Round, July 1993-June 1994), Report No: 438, June 1998. 8. Employment and Unemployment Situation among Religious Groups in India 1999-2000. NSS 55th Round (July 1999-June 2000) Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, September 2001. Employment Status of Muslims in Andhra Pradesh 9. -

Hindu Castes and Sects an Exposition of the Origin of the Hindu Caste

HINDU CASTES AND SECTS. PREF A.CE. IN the last edition of my" Commentaries on Hindu Law" I devoted a chapter to the Hindn Caste System which attracted the attention of the Publishers, and they suggested that the subject might well be expanded so as to be brought out as a separate volume. They suggested also that, in order to make the book complete, I should give an account not only of the Castes, but also of the important Hindu Sects, some of which are practically so many ""new Castes. As I had heen already engaged in writing a book about the hisfury and philosophy of religions, the prp posal, so far as the sects were concerned, was welcome indeed. About the Castes I felt very considerable diffidence; but it seemed to me that, in a town like Calcutta, where there are men from every part of India, it might not be quite impossible to collect the necessary information. When, however, I actually commenced my enquiries, then I fully realised the difficulty of my task. The original information contained in this work has been derived from a very large number of Hindn gentlemen hailing from different parts of India. I here iv PRBFACK. gratefully acknowledge the kindness that they have shown in according to me their assistance. I feel very ;trongly inclined to insert in this book a list of their names. But the publication of snch a list is not de sirable for more reasons than one. To begin with, such a list would be necessarily too long to be conveniently included. -

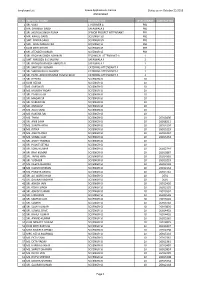

Employee List for Rti As on 25-Oct-2018

Employee List Space Applications Centre Status as on October 25,2018 Ahmedabad Sr.No. EMPLOYEE NAME DESIGNATION LEVEL/GRADE CONTACT NO 1 SRI. VIJAY L V DRIVER A PB1 2 MR. SHANKER SINGH SAFAIWALA B PB1 3 SRI. JAGDISH SINGH PUNIA SENIOR PROJECT ATTENDANT PB1 4 MR. RAHUL GARG SCI/ENGR-SD PB3 5 SMT. BINDIA SAHU SCI/ENGR-SD PB3 6 SMT. ANJU MALHOTRA SCI/ENGR-SE PB3 7 KUM KRITI KHATRI SCI/ENGR-SE PB3 8 SRI. JITENDER KUMAR SCI/ENGR-SE PB3 9 SRI. BACHAN SINGH ADHIKARI TECHNICAL ATTENDANT-A 1 10 SMT. NIRUBEN B CHAUHAN SAFAIWALA A 1 11 SRI. RATHOD MANISH AMRUTLAL SAFAIWALA A 1 12 SRI. SANTOSH KUMAR CATERING ATTENDANT-A 1 13 SRI. SHIRISH BALU GHARDE CATERING ATTENDANT-A 1 14 SRI. PATEL AKSHAYKUMAR YOGESHBHAI CATERING ATTENDANT-A 1 15 SRI. DEEPAK SCI/ENGR-SC 10 16 KUM HEENA SCI/ENGR-SC 10 17 MS. SARSWATI SCI/ENGR-SC 10 18 MS. MONIKA YADAV SCI/ENGR-SC 10 19 SRI. PANKAJ JAIN SCI/ENGR-SC 10 20 SRI. MADAR SK SCI/ENGR-SC 10 21 SRI. VARENYAM SCI/ENGR-SC 10 22 SRI. JISHAD M SCI/ENGR-SC 10 23 MS. ALKA SAINI SCI/ENGR-SC 10 24 MS. RAKSHA RAI SCI/ENGR-SC 10 25 MS. TANVI SCI/ENGR-SC 10 26918406 26 SRI. ANIK SAHA SCI/ENGR-SC 10 26918211 27 MS. SUNITA ARYA SCI/ENGR-SC 10 26914194 28 MS. RITIKA SCI/ENGR-SC 10 26915219 29 MS. ANKITA RANI SCI/ENGR-SC 10 26915234 30 MS. SONALI JAIN SCI/ENGR-SC 10 26915234 31 SRI. -

Udfngrzq Rq Plvohdglqj Dgv Ihdwxulqj Fhoheulwlhv

() 9 $#01$ !+ (" 1$ !+ +,#-+. /01 .''/ *+,- &.+01 )#(!2 3 2 4: B 3 3 4 ? ? 34 2 @ A @ ; )*5<++' <=< ; 4)$" ++$# 2 3 1245 67 08 ! " ! ! # # lution, we invited suggestions $ ! % from the public. he odd-even scheme will “We have received 1,200 Tbe rolled out in the nation- suggestions. Many residents al Capital from November 4 to and experts have strongly sup- embers of the Legislative November 15, said Delhi Chief ported implementation of the MAssembly of Jharkhand Minister Arvind Kejriwal on scheme in peak pollution peri- today gathered for the first time Friday. He also announced a od. Their recommendation was in the one-day special session slew of measures to mitigate that odd-even policy is a very of the House just a day after the pollution during winter effective measure, particularly inauguration of the new months due to stubble burning in winter months. We have Assembly building by Prime in neighbouring States. started making preparations Minister Narendra Modi and Kejriwal laid emphasis on to implement the odd-even were awestruck with the mag- seven-point action plan to scheme in Delhi.” nificence of the House that the combat winter air pollution. Kejriwal said the details of State got after 19 long years of The Government has set spe- the 12-day scheme will be wait. Almost all members, cial plans for 12 pollution hot shared with Delhiites in com- except those from the spots in the city. Among them ing days. Vehicles are expect- Jharkhand Mukti Morcha, ! " mass distribution of masks, ed to ply alternately on odd and the polluted air and lem. -

Folk Art” Reevaluating Bengali Scroll Paintings

Beatrix Hauser University o f Frankfurt/Main From Oral Tradition to “Folk Art” Reevaluating Bengali Scroll Paintings Abstract This article contributes to the scholarship on the politics of production and consump tion of the arts in modern India as well as to relating issues of aesthetics and develop ment. It describes the tradition of scroll painters— Patuas (patuya)— and the practice of storytelling in contemporary West Bengal, where a small number of picture showmen who follow this caste-based occupation can still be found. In this article the process by which this tradition was recognized as “folk art” is analyzed and a shift of genre from a primarily oral tradition to a primarily visual tradition (i.e., from the performance of scrolls to their selling as art products) is demonstrated. It is argued that “Patua art,” as it is perceived today, is a quite recent phenomenon, generated to a great extent by the urban intellectual elite of Calcutta. Keywords: Storytelling— scroll painting— folk art— politics of authenticity— Bengal Asian Folklore Studies, Volume 61,2002: 105—122 HOULD YOU COME to Calcutta one day, you might be invited to the house of a Bengali family. And while you are in their house, a Patua Smight happen to call in. Your host will introduce him as a atradition al scroll painter,” who comes by from time to time to sell his scrolls. He will ask you whether you are interested in seeing his paintings. Okay, why not? Both of you go out on the veranda, where the old man is already waiting for you. -

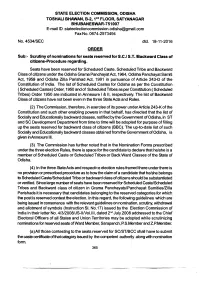

ORDER Sub:- Scrutiny of Nominations for Seats Reserved for SC

STATE ELECTION COMMISSION, ODISHA TOSHALIBHAWAN, B-2,1ST FLOOR, SATYANAGAR BHUBANESWAR-751007 E-mail ID :[email protected] Fax No. 0674-2573494 No. 4534/SEC dtd. 18-11-2016 ORDER Sub:- Scrutiny of nominations for seats reserved for S.C./ S.T. /Backward Class of citizens-Procedure regarding. Seats have been reserved for Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe and Backward Class of citizens under the Odisha Grama Panchayat Act, 1964, Odisha Panchayat Samiti Act, 1959 and Odisha Zilla Parishad Act, 1991 in pursuance of Article 243-D of the Constitution of India. The list of Scheduled Castes for Odisha as per the Constitution ( Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950 and of Scheduled Tribes as per Constitution ( Scheduled Tribes) Order 1950 are indicated in Annexure I & II, respectively. The list of Backward Class of citizens have not been even in the three State Acte and Rules. (2) The Commission, therefore, in exercise of its power under Article 243-K of the Constitution and such other enabling powers in that behalf, has directed that the list of Socially and Educationally backward classes, notified by the Government of Odisha, in ST and SC Development Department from time to time will be adopted for purpose of filling up the seats reserved for backward class of citizens (BBC). The up-to-date list of such Socially and Educationally backward classes obtai ned from the Government of Odisha, is given inAnnexure III. (3) The Commission has further noted that in the Nomination Forms prescribed under the three election Rules, there is space for the candidate to declare that he/she is a member of Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribes or Back Ward Classes of the State of Odisha. -

Page1final.Qxd (Page 3)

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 20, 2021 (PAGE 6) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU From page 1 Achieve specified core benchmarks SC paves way for construction of NH Co-WIN App almost collapses, 3 infiltrators killed on LoC in Bench of J&K High Court. The aggrieved persons. expeditiously: CS to Admn Secys High Court on December 31, Court with regard to compen- badly hits vaccination in J&K Khour sector, 4 jawans injured while hearing the appeal filed by sation part, has been informed achieve the benchmarks in core include Rs 90,000 crore liquidi- vaccine. said to be doing well. Meanwhile, police and Special e-Mohammed militants arrested the persons whose land was that there is error in payment areas to receive the borrowings ty infusion to DISCOMS as a Further, the authorities have In this regard, a video mes- Operation Group (SOG) teams in Ramban district yesterday had acquired for the purpose of the process to the rightful owners and from the Government of India”, concessional loan offering by been permitted to use offline sage was put out by the Director today took two arrested militants disclosed that they had picked up project, had directed for main- the same can be corrected and the sources said quoting the direc- PFC &REC Limited, tariff pol- mode for vaccination in view of SKIMS, Dr A G Ahanger in of Jaish-e-Mohammed outfit to the consignment of arms, ammu- taining status quo with regard to compensation can be paid to the tions issued by the Chief icy reforms encompassing con- slow speed of Internet due to 2G which he said that he along with the International Border (IB) in nition and explosives from the the land in question. -

REVISION of 'Tlfesjjist.'Vof SCHEDULED Ofgtes Anfi

REVISIONv OF 'TlfEsJjIST.'VOf Svv'vr-x'- " -?>-•'. ? ••• '■gc^ ’se v ^ - - ^ r v ■*■ SCHEDULED OfgTES ANfi SCHEDULED-TIBBS' g o VESNMEbrr pF ,i^d£4 .DEI^Ap’MksfT OF.SOCIAL SEmFglTY THE REPORT OF THE ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON THE REVISION OF THE LISTS OF SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES GOVERNMENT OF INDIA DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL SECURITY CONTENTS PART I PTER I. I n t r o d u c t i o n ............................................................. 1 II. Principles and P o l i c y .................................................... 4 III. Revision o f L i s t s .............................................................. 12 IV. General R eco m m en d a tio n s.......................................... 23 V. Appreciation . 25 PART II NDJX I. List of Orders in force under articles 341 and 342 of the Constitution ....... 28 II. Resolution tonstituting the Committee . 29 III, List of persons 'who appeared before the Committee . 31 (V. List of Communities recommended for inclusion 39 V. List of Communities recommended for exclusion 42 VI, List of proposals rejected by the Committee 55 SB. Revised Statewise lists of Scheduled Castes and . Scheduled T r i b e s .................................................... ■115 CONTENTS OF APPENDIX 7 1 i Revised Slantwise Lists pf Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Sch. Sch. Slate Castes Tribes Page Page Andhra Pracoih .... 52 9i rtssam -. •S'S 92 Bihar .... 64 95 G u j a r a i ....................................................... 65 96 Jammu & Kashmir . 66 98 Kerala............................................................................... 67 98 Madhya Pradesh . 69 99 M a d r a s .................................................................. 71 102 Maharashtra ........................................................ 73 103 Mysore ....................................................... 75 107 Nagaland ....................................................... 108 Oriisa ....................................................... 78 109 Punjab ...... 8i 110 Rejssth&n ...... -

INDIAN MUSLIM WOMEN Al\L ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDIAN MUSLIM WOMEN Al\l ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LIBRARY SCIENCE X882-~83 BY GULAM GHOUSE Roll No. 8 Enrolment No. R-2430 Under the supervision of Mr. S. MUSTAFA ZAIDI LECTURER DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH-20200\ (India) F«bruary 14, 1984 This ia to cartlfy that this disssrtation uias compiled undsr my •upcrvlslon and guidanca and the work la done to my aatiafaetion. ( S. PluatafaUaidi ) Lecturer tT F«d in ComDUtfe- DS1073 CHEC:rD-200 2 iO MX^KmxD&EmEm; Words seem to be Insufficient to express my deep sense of gratitude to my respected teacher Mr* Mustafa K.Q. £aidi« Lecturer* Department of Library science, for his patient* guidance* cooperation and invaluable suggestions during the formative stage of this work* I am also gratefully thankful to Professor M.H.Razvl* University Librarian and Chainoan* Department of Library science* Aligarh Muslim University* Aligarh* who* besides putting necessary facilities at my disposal and guiding me in my choice of courses and studies* also gave me personal help to make my stay in this institution a success. I am indebted specially to rir, Hasan Zaenarud, Lectucer* Department of Library science* for his Invaluable suggestions and worthy advice throughout my stay in the Department and for unsparing help and encourag€Knent. I owe a deep sense of indebtedness to Mr* Saiyid Haraid* Vice-^Chancelior* Aligarh Mu8^,lmNjniversity* Aligarh* for providing financial aid to complete my work. I must also thank Dr. Masood All Khao* Sr.