Excerpts from Finishing the Hat by Stephen Sondheim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education Resource Stephen Sondheim & James Lapine

Stephen Sondheim & James Lapine INTO THE WOODS Education Resource Music INTO THE WOODS - MUSIC RESOURCE INTRODUCTION From the creators of Sunday in the Park with George comes Into the Woods, a darkly enchanting story about life after the ‘happily ever after’. Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine reimagine the magical world of fairy tales as the classic stories of Jack and the Beanstalk, Cinderella, Little Red Ridinghood and Rapunzel collide with the lives of a childless baker and his wife. A brand new production of an unforgettable Tony award-winning musical. Into the Woods | Stephen Sondheim & James Lapine. 19 – 26 July 2014 | Arts Centre Melbourne, Playhouse Music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by James Lapine Originally Directed on Broadway by James Lapine By arrangement with Hal Leonard Australia Pty Ltd Exclusive agent for Music Theatre International (NY) 2 hours and 50 minutes including one interval. Victorian Opera 2014 – Into the Woods Music Resource 1 BACKGROUND Broadway Musical Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book and Direction by James Lapine Orchestration: Jonathan Tunick Opened in San Diego on the 4th of December 1986 and premiered in Broadway on the 5th of November, 1987 Won 3 Tony Awards in 1988 Drama Desk for Best Musical Laurence Olivier Award for Best Revival Figure 1: Stephen Sondheim Performances Into the Woods has been produced several times including revivals, outdoor performances in parks, a junior version, and has been adapted for a Walt Disney film which will be released at the end of 2014. Stephen Sondheim (1930) Stephen Joshua Sondheim is one of the greatest composers and lyricists in American Theatre. -

Determining Stephen Sondheim's

“I’VE A VOICE, I’VE A VOICE”: DETERMINING STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE THROUGH A MUSIC-THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF HIS THEATER WORKS BY ©2011 PETER CHARLES LANDIS PURIN Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ___________________________ Chairperson Dr. Scott Murphy ___________________________ Dr. Deron McGee ___________________________ Dr. Paul Laird ___________________________ Dr. John Staniunas ___________________________ Dr. William Everett Date Defended: August 29, 2011 ii The Dissertation Committee for PETER PURIN Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “I’VE A VOICE, I’VE A VOICE”: DETERMINING STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE THROUGH A MUSIC-THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF HIS THEATER WORKS ___________________________ Chairperson Dr. Scott Murphy Date approved: August 29, 2011 iii Abstract This dissertation offers a music-theoretic analysis of the musical style of Stephen Sondheim, as surveyed through his fourteen musicals that have appeared on Broadway. The analysis begins with dramatic concerns, where musico-dramatic intensity analysis graphs show the relationship between music and drama, and how one may affect the interpretation of events in the other. These graphs also show hierarchical recursion in both music and drama. The focus of the analysis then switches to how Sondheim uses traditional accompaniment schemata, but also stretches the schemata into patterns that are distinctly of his voice; particularly in the use of the waltz in four, developing accompaniment, and emerging meter. Sondheim shows his harmonic voice in how he juxtaposes treble and bass lines, creating diagonal dissonances. -

INTO the WOODS Stephen Sondheim (Music and Lyrics) and James Lapine (Book) Directed by Susi Damilano Music Director: Dave Dobrusky Choreography: Kimberly Richards

Press Release For immediate release May 2014 [email protected] Download Hi Res photos here INTO THE WOODS Stephen Sondheim (music and lyrics) and James Lapine (book) Directed by Susi Damilano Music Director: Dave Dobrusky Choreography: Kimberly Richards June 24th to September 6th Previews June 24 – June 27 at 8pm Tuesdays through Thursdays at 7pm, Fridays and Saturdays at 8pm Saturdays at 3pm and Sundays at 2pm (except 6/29) PRESS OPENING: Saturday, June 28th at 8pm San Francisco, CA (May 2014) – San Francisco Playhouse (Artistic Director Bill English & Producing Director Susi Damilano) concludes its provocative eleventh season with Into the Woods by Stephen Sondheim (music and lyrics) and James Lapine (book). What happens after “happily ever after?” Fractured fairy tales of a darker hue provide the context for Into the Woods, which deconstructs the Brothers Grimm by way of “The Twilight Zone.” While the faces and names are familiar, Cinderella, Rapunzel, Little Red Riding Hood, Jack in the Beanstalk and company inhabit a sylvan neighborhood in which witches and bakers are next-door neighbors, handsome princes from once-parallel fables are competitive (and equally vain) brothers, and all the stories intersect through unexpected new plot twists. Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s beloved musical intertwines classic fairytales with a contemporary edge to tell stories of wishes granted and “the price” paid. Susi Damilano (Director), Dave Dobrusky (Music Director) and Kimberly Richards (Choreographer) will team up to bring a fresh twist to this familiar tale by adding a time-travelling boy, Ian DeVaynes to the Bay Area cast that features: Louis Parnell* (Narrator), Safiya Fredericks* (Witch), El Beh (Baker’s Wife), Keith Pinto* (Baker), Tim Homsley* (Jack), Joan Mankin* (Jack’s Mom), Monique Hafen* (Cinderella), Becka Fink (Cinderella’s Stepmom), identical twins, Lily and Michelle Drexler (Cinderella’s Stepsisters), Noelani Neal (Rapunzel), Corinne Proctor (Red), Ryan McCrary and Jeffrey Adams (Princes/Wolves) and John Paul Gonzales (Steward). -

Download Finishing the Hat: Collected Lyrics (1954-1981) with Attendant

Finishing the Hat: Collected Lyrics (1954-1981) with Attendant Comments, Principles, Heresies, Grudges, Whines and Anecdotes by Stephen Sondheim Ebook Finishing the Hat: Collected Lyrics (1954-1981) with Attendant Comments, Principles, Heresies, Grudges, Whines and Anecdotes currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Finishing the Hat: Collected Lyrics (1954-1981) with Attendant Comments, Principles, Heresies, Grudges, Whines and Anecdotes please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Hardcover:::: 480 pages+++Publisher:::: Knopf; First Edition edition (October 26, 2010)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 0679439072+++ISBN-13:::: 978-0679439073+++Product Dimensions::::8.4 x 1.1 x 11.1 inches++++++ ISBN10 0679439072 ISBN13 978-0679439 Download here >> Description: Stephen Sondheim has won seven Tonys, an Academy Award, seven Grammys, a Pulitzer Prize and the Kennedy Center Honors. His career has spanned more than half a century, his lyrics have become synonymous with musical theater and popular culture, and in Finishing the Hat—titled after perhaps his most autobiographical song, from Sunday in the Park with George—Sondheim has not only collected his lyrics for the first time, he is giving readers a rare personal look into his life as well as his remarkable productions.Along with the lyrics for all of his musicals from 1954 to 1981—including West Side Story, Company, Follies, A Little Night Music and Sweeney Todd—Sondheim treats us to never-before-published songs from each show, songs that were cut or discarded before seeing the light of day. He discusses his relationship with his mentor, Oscar Hammerstein II, and his collaborations with extraordinary talents such as Leonard Bernstein, Arthur Laurents, Ethel Merman, Richard Rodgers, Angela Lansbury, Harold Prince and a panoply of others. -

Stephen Sondheim. Finishing The

158 Context 37 (2012) powerless before the appeal of Wagner’s music and the spiritual heights of its enjoyment’ (p. 64). Yet this statement directly contradicts the findings of existing (and more in-depth) research on the French response to Eine Kapitulation; Steven Huebner and Thomas S. Grey, among others, have argued that Wagner’s anti-French farce had a profound impact on French musical life.4 In this context it seems difficult to justify du Quenoy’s conclusion about the powerlessness of earthly concerns such as nationalism in the face of the spiritual power of Wagner’s music. Du Quenoy’s professed ‘ecstasy’ at the prospect of separating art from politics remains puzzling. Throughout the book he maintains that, despite the entanglement of Wagner and politics in France, Wagner’s music triumphed because people kept listening to it. But perhaps people continued to listen to Wagner for the very reason that it engaged with politics rather than operating in isolation from it. This proposition would entail considering ‘politics’ in a broader sense than du Quenoy seems to do, encompassing more than simply relations between France and Germany. Nevertheless, it would be a more productive and interesting way of examining the fascinating, complex and ongoing relationship between Wagner and the French. 4 Thomas S. Grey, ‘Eine Kapitulation: Aristophanic Operetta as Cultural Warfare in 1870,’ Richard Wagner and His World, 87–122; Steven Huebner, ‘Introduction,’ French Opera at the Fin de Siècle: Wagnerism, Nationalism, and Style (Oxford: OUP, 1999), 1–22. Stephen Sondheim. Finishing the Hat: Collected Lyrics (1954–1981) with Attendant Comments, Principles, Heresies, Whines and Anecdotes New York: Knopf, 2010 ISBN 978-0-679-43907-3. -

Anthony De Mare, Piano Re-Imagining Sondheim from the Piano

Sunday, November 5, 201 7, 7pm Hertz Hall Anthony de Mare, piano Re-Imagining Sondheim from the Piano PROGRAM (all works based on material by Stephen Sondheim) andy akiHo into the Woods (2013) (Into the Woods ) William boLcoM a Little Night fughetta (2010) (after “anyone can Whistle” & “Send in the clowns”) ricky ian GorDoN Every Day a Little Death (2008/2010) (A Little Night Music ) annie GoSfiELD a bowler Hat (2011) (Pacific Overtures ) Mason batES very Put together (2012) (after “Putting it together” from Sunday in the Park with George ) Steve rEicH finishing the Hat –two Pianos (2010) (Sunday in the Park with George ) Gabriel kaHaNE being alive (2011) (Company ) Ethan ivErSoN Send in the clowns (2011) (A Little Night Music ) Wynton MarSaLiS that old Piano roll (2014) (Follies ) thomas NEWMaN Not While i’m around (2012) (Sweeney Todd ) Duncan SHEik Johanna in Space (2014) (after “Johanna” from Sweeney Todd ) Jake HEGGiE i’m Excited. No You’re Not. (2010) (after “a Weekend in the country” from A Little Night Music ) All pieces were commissioned expressly for the Liaisons Project, Rachel Colbert and Anthony de Mare, producers. Cal Performances’ 2017 –18 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 27 PROGRAM NOTES ike many of us, i have long held in highest COMPOSER COMMENTS esteem the work of Stephen Sondheim, Lwhose fearless eclecticism has emboldened Andy Akiho: “ the first time i listened to it i loved many a musical risk-taker. over the years, i often the concept of Into the Woods —being lost in and found myself imagining how the familiar and confused by the woods, and the consistent and beloved songs of the Sondheim canon would driving rhythms of the opening prologue. -

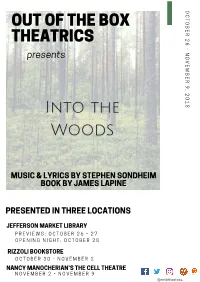

Into the Woods Program

O C T OUT OF THE BOX O B E R THEATRICS 2 6 - N presents O V E M B E R 9 , 2 0 1 8 MUSIC & LYRICS BY STEPHEN SONDHEIM BOOK BY JAMES LAPINE PRESENTED IN THREE LOCATIONS JEFFERSON MARKET LIBRARY P R E V I E W S : O C T O B E R 2 6 - 2 7 O P E N I N G N I G H T : O C T O B E R 2 8 RIZZOLI BOOKSTORE O C T O B E R 3 0 - N O V E M B E R 1 NANCY MANOCHERIAN’S THE CELL THEATRE N O V E M B E R 2 - N O V E M B E R 9 @ootbtheatrics CAST Amara J. Brady Gabriella Garcia Alie B. Gorrie* Alicia Krakauer* Alaina Mills* Celena Vera Morgan Sydney Ronis Brian Charles Katherine Yacko* Rooney* * Actors' Equity Association MUSICAL NUMBERS ACT I Prologue: "Into the Woods" "Hello, Little Girl" "I Guess This is Goodbye" "Maybe They're Magic" "I Know Things Now" "A Very Nice Prince" "Giants in the Sky" "Agony" "It Takes Two" "Stay With Me" "On the Steps of the Palace" "Ever After" ACT II Prologue: "So Happy" "Agony" "Lament" "Any Moment' "Moments in the Woods" "Your Fault" "Last Midnight" "No More" "No One is Alone" Finale: "Children Will Listen" MUSICIANS Piano.....................................................................................................Anessa Marie Into the Woods will be performed with an intermission. Run Time: 2 hours 40 minutes Opening Night: October 28, 2018 nancy manocherian’s Jefferson Market Library RIzzoli Bookstore the cell theatre 425 Avenue of the Americas 1133 Broadway 338 W. -

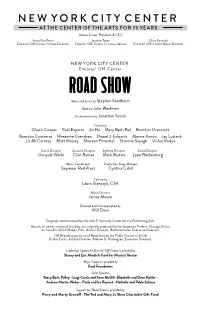

Read the Road Show Program

NEW YORK CITY CENTER AT THE CENTER OF THE ARTS FOR 75 YEARS Arlene Shuler, President & CEO Anne Kauffman Jeanine Tesori Chris Fenwick Encores! Off-Center Artistic Director Encores! Off-Center Creative Advisor Encores! Off-Center Music Director NEW YORK CITY CENTER Encores! Off-Center Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by John Weidman Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Featuring Chuck Cooper Raúl Esparza Jin Ha Mary Beth Peil Brandon Uranowitz Brandon Contreras Rheaume Crenshaw Daniel J. Edwards Marina Kondo Jay Lusteck Liz McCartney Matt Moisey Shereen Pimentel Sharone Sayegh Vishal Vaidya Scenic Designer Costume Designer Lighting Designer Sound Designer Donyale Werle Clint Ramos Mark Barton Leon Rothenberg Music Coordinator Production Stage Manager Seymour Red Press Cynthia Cahill Casting by Laura Stanczyk, CSA Music Director James Moore Directed and Choreographed by Will Davis Originally commissioned by the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Bounce, an earlier version of this play, was originally produced by the Goodman Theatre, Chicago, Illinois on June 30, 2003 (Robert Falls, Artistic Director; Roche Schulfer, Executive Director). Off-Broadway premiere of Road Show by the Public Theater in 2008 (Oskar Eustis, Artistic Director; Andrew D. Hamingson, Executive Director). Leadership Support for Encores! Off-Center is provided by Stacey and Eric Mindich Fund for Musical Theater Major Support is provided by Ford Foundation Series Sponsors Stacy Bash-Polley • Luigi Caiola and Sean McGill • Elizabeth and Dean Kehler • -

Feminist Periodicals

The Un vers ty of W scons n System Feminist Periodicals A current listing of contents WOMEN'S STUDIES Volume 23, Numbers 1 & 2, Spring & Summer 2003 Published by Phyllis Holman Weisbard LIBRARIAN Women's Studies Librarian Feminist Periodicals A current listing of contents Volume 23, Numbers 1 & 2, Spring & Summer 2003 Periodical literature is the culling edge of women's scholarship, feminist theory, and much of women's culture. Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing of Contents is pUblished by the Office of the University of Wisconsin System Women's Studies Librarian on a quarterly basis with the intent of increasing public awareness of feminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminist Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with a wide spectrum of feminist periodicals; and to provide the requisite bibliographic information should a reader wish to subscribe to a journal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Table of contents pages from current issues of major feminist journals are reproduced in each issue of Feminist Periodicals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing of all journals we have selected. As pUblication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of FP. The annotated listing provides the following information on each journal: 1. Year of first pUblication. 2. Frequency of publication. 3. -

The Prehistory and Reception of Leonard Bernstein's Missa

The prehistory and reception of Leonard Bernstein’s Missa Brevis (1988) by Patrick Connor Dittamo B.A., College of William and Mary, 2013 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC School of Music, Theatre, and Dance College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2019 Approved by: Major Professor Craig Weston Copyright © 2019 Patrick Connor Dittamo. All rights reserved. Abstract Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) commonly repurposed previously-written material in new compositions, including his Missa Brevis (1988), which adapted significant portions of his incidental music for Lillian Hellman’s play The Lark (1955), itself an adaptation of French playwright Jean Anouilh’s play L’Alouette (1953) about the trial of Joan of Arc. Based on an assessment of The Lark’s mixed reception history as a play, Bernstein’s score, recorded by the New York Pro Musica, deserves some credit for the original Broadway run’s considerable success. Bernstein’s Medieval- and Renaissance-inflected score was written shortly before the play’s tryout run in Boston, and used fragments of verse by Adam de la Halle (c. 1245-1288/1306) and Jean-Antoine de Baïf (1532-1589), as well as the tune of the French folksong “Plantons la Vigne,” and not the commonly-cited “Vive la Grappe.” Bernstein and the New York Pro Musica were well- compensated for their contributions to The Lark; however, during the play’s national tour, there was a pay dispute over reduced royalties between Bernstein’s agent and the play’s management. Before the New York premiere of The Lark, Bernstein expressed a belief that its incidental score held a viable “kernel of a short mass,” and considered using a Lark-based missa brevis to fulfill a commission for Juilliard’s fiftieth anniversary, an idea he ultimately abandoned. -

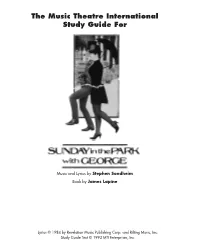

Study Guide-Sunday in the Park

The Music Theatre International Study Guide For Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by James Lapine Lyrics © 1984 by Revelation Music Publishing Corp. and Rilting Music, Inc. Study Guide Text © 1993 MTI Enterprises, Inc. Table Of Contents About Sunday In The Park With George.......................3 The Characters in Sunday In The Park With George .............5 Plot Synopsis .............................................7 Themes and Topics to Explore (Questions and Assignments) .....................................13 The Visual Artist ........................................13 The Artist in Society ......................................14 Impressionism ..........................................15 Modern Art ............................................15 The Artist and Interpersonal Relationships ......................16 The Painting ...........................................17 Family Trees ...........................................17 Sunday in the Park with George as a Theatrical Metaphor for Seurat’s Masterpiece ...................18 Sunday in the Park with George as a Metaphor for the Struggles of Contemporary Broadway Authors and Composers .............18 Sunday in the Park with George as a Musical Theatre Work ............19 The Musical Theatre Elements of Sunday in the Park with George ........20 Create Your Own Musical ..................................21 Critical Analysis ........................................21 Appendix ...............................................22 About the Creation of Sunday in the Park with George -

FOLLIES Ing Been Doing So for Forty Years

FOLLIES ing been doing so for forty years. Sondheim’s score was permill Playhouse version, and the most recent revival – brilliant and breathtaking – it worked its wonders on so all have their strengths and joys, all have lots more music, many levels, from pastiche that was much more than pas - and none are the original. tiche, to some of the greatest character-driven musical nce upon a time there was a Broadway that was theater songs ever written. The mix on the original album was odd, with vocals being not run by the film business, by corporations, and occasionally overpowered by a suddenly blaring orches - Othere were Broadway musicals that didn’t have The title of the show is perfect and problematic at the tra, or vocals hard-panned left and right (that’s okay for twenty-three producers above the title. And in that long- same time – at least it was for audiences who bought their one line, but to hear an entire solo hard-panned to the left ago Broadway world there were some truly adventure - tickets thinking they’d be seeing an old-fashioned Follies or right is just really strange). Having had great luck remix - some people who were not content to sit and do what was show. But that’s the brilliance of it – nothing is what it ing two problematic cast albums, Promises, Promises and currently popular – they wanted to push the form, to ham - seems on the surface. There are cracks everywhere, in - Sugar , I began to think about Follies , wondering if that mer through conventional walls, to push the boundaries cluding the amazing Byrd logo of the Follies girl’s face.