2020 CPLC Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 01 Aug 31.Indd

ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED NEWSPAPER Top Qatari India spin to business team win against visits Kenya England Business | 17 Sport | 27 Sunday 31 August 2014 • 5 Dhu’l-Qa’da 1435 • Volume 19 Number 6174 www.thepeninsulaqatar.com [email protected] | [email protected] Editorial: 4455 7741 | Advertising: 4455 7837 / 4455 7780 Gulf states ready Jeddah meet ‘resolves’ envoy row to help counter jihadist advance GCC foreign ministers agree on terms and criteria for return of envoys to Qatar JEDDAH: Gulf Arab states said yesterday that they were DOHA: The diplomatic dead- ready to help counter advances lock between Qatar and its by jihadists in Syria and Iraq, three GCC peers — Saudi after the US called for a global Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain coalition to fight the militants. — is likely to end soon, with But the six-nation Gulf Kuwait’s First Deputy Prime Cooperation Council said it was Minister and Foreign Minister awaiting details from Washington saying that the ambassadors of and a visit to the region by US the three countries could return Secretary of State Department to Doha “any moment”, Qatar John Kerry to discuss anti-jihad- News Agency (QNA) reported ist cooperation. yesterday. A GCC statement said Gulf The issue was discussed at states are ready to act “against length at the meeting of the for- terrorist threats that face the eign ministers of the GCC states region and the world”. (held in Jeddah yesterday) and The GCC foreign ministers also the terms and criteria for the pledged a readiness to fight “ter- return of the envoys have been rorist ideology which is contrary agreed upon. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-19605-6 — Boundaries of Belonging Sarah Ansari , William Gould Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-19605-6 — Boundaries of Belonging Sarah Ansari , William Gould Index More Information Index 18th Amendment, 280 All-India Muslim Ladies’ Conference, 183 All-India Radio, 159 Aam Aadmi (Ordinary Man) Party, 273 All-India Refugee Association, 87–88 abducted women, 1–2, 12, 202, 204, 206 All-India Refugee Conference, 88 abwab, 251 All-India Save the Children Committee, Acid Control and Acid Crime Prevention 200–201 Act, 2011, 279 All-India Scheduled Castes Federation, 241 Adityanath, Yogi, 281 All-India Women’s Conference, 183–185, adivasis, 9, 200, 239, 261, 263, 266–267, 190–191, 193–202 286 All-India Women’s Food Council, 128 Administration of Evacuee Property Act, All-Pakistan Barbers’ Association, 120 1950, 93 All-Pakistan Confederation of Labour, 256 Administration of Evacuee Property All-Pakistan Joint Refugees Council, 78 Amendment Bill, 1952, 93 All-Pakistan Minorities Alliance, 269 Administration of Evacuee Property Bill, All-Pakistan Women’s Association 1950, 230 (APWA), 121, 202–203, 208–210, administrative officers, 47, 49–50, 69, 101, 212, 214, 218, 276 122, 173, 176, 196, 237, 252 Alwa, Arshia, 215 suspicions surrounding, 99–101 Ambedkar, B.R., 159, 185, 198, 240, 246, affirmative action, 265 257, 262, 267 Aga Khan, 212 Anandpur Sahib, 1–2 Agra, 128, 187, 233 Andhra Pradesh, 161, 195 Ahmad, Iqbal, 233 Anjuman Muhajir Khawateen, 218 Ahmad, Maulana Bashir, 233 Anjuman-i Khawateen-i Islam, 183 Ahmadis, 210, 268 Anjuman-i Tahafuuz Huqooq-i Niswan, Ahmed, Begum Anwar Ghulam, 212–213, 216 215, 220 -

Pakistan Was Suspended by President General Musharaff in March Last Year Leading to a Worldwide Uproar Against This Act

A Coup against Judicial Independence . Special issue of the CJEI Report (February, 2008) ustice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry, the twentieth Chief Justice of Pakistan was suspended by President General Musharaff in March last year leading to a worldwide uproar against this act. However, by a landmark order J handed down by the Supreme Court of Pakistan, Justice Chaudhry was reinstated. We at the CJEI were delighted and hoped that this would put an end to the ugly confrontation between the judiciary and the executive. However our happiness was short lived. On November 3, 2007, President General Musharaff suspended the constitution and declared a state of emergency. Soon the Pakistan army entered the Supreme Court premises removing Justice Chaudhry and other judges. The Constitution was also suspended and was replaced with a “Provisional Constitutional Order” enabling the Executive to sack Chief Justice Chaudhry, and other judges who refused to swear allegiance to this extraconstitutional order. Ever since then, the judiciary in Pakistan has been plunged into turmoil and Justice Chaudhry along with dozens of other Justices has been held incommunicado in their homes. Any onslaught on judicial independence is a matter of grave concern to all more so to the legal and judicial fraternity in countries that are wedded to the rule of law. In the absence of an independent judiciary, human rights and constitutional guarantees become meaningless; the situation capable of jeopardising even the long term developmental goals of a country. As observed by Viscount Bryce, “If the lamp of justice goes out in darkness, how great is the darkness.” This is really true of Pakistan which is presently going through testing times. -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

View of Above, It Is Observed That Instant Petition (C.P

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SINDH, CIRCUIT COURT, HYDERABAD Present: Mr. Justice Abdul Maalik Gaddi Mr. Justice Khadim Hussain Tunio 1. C.P No.D- 3183 of 2018 Dr. Fateh Muhammad Burfat --------- Petitioner Versus Province of Sindh and others --------- Respondents 2. C.P No.D- 3206 of 2018 Prof. Dr. Muneeruddin --------- Petitioner Versus Province of Sindh and others --------- Respondents 3. C.P No.D- 1874 of 2019 Dr. Arfana Mallah --------- Petitioner Versus Federation of Pakistan and others --------- Respondents 4. CP No.D- 2380 of 2019 Dr. Fateh Muhammad Burfat -------- Petitioner Versus Province of Sindh and others -------- Respondents 2 Date of Hearings : 6.02.2020, 03.03.2020 & 10.03.2020 Date of order : 10.03.2020 Mr. Rafique Ahmed Kalwar Advocate for Petitioner in C.P. Nos.D- 3183 of 2018, 2380 of 2019 and for Respondent No.5 in C.P. No.D- 1874 of 2019. Mr. Shabeer Hussain Memon, Advocate for Petitioner in C.P. No.D- 3206 of 2018. Mr. K.B. Lutuf Ali Laghari Advocate for Petitioner in C.P. No.D- 1874 of 2019 and intervener in C.P. No.D- 2380 of 2019. Mr. Allah Bachayo Soomro, Additional Advocate General, Sindh alongwith Jawad Karim AD (Legal) ACE Jamshoro on behalf of ACE Sindh. Mr. Kamaluddin Advocate also appearing for Respondent No.5 in C.P. No.D- 1874 of 2019. None present for respondent No.1 (Federation of Pakistan) in C.P. No.D-1874/2019. O R D E R ABDUL MAALIK GADDI, J.- By this common order, we intend to dispose of aforementioned four constitutional petitions together as a common question of facts and law is involved in all these petitions as well as the subject matter is also interconnected. -

Politics of Sindh Under Zia Government an Analysis of Nationalists Vs Federalists Orientations

POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Chaudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan Dedicated to: Baba Bullay Shah & Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai The poets of love, fraternity, and peace DECLARATION This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………………….( candidate) Date……………………………………………………………………. CERTIFICATES This is to certify that I have gone through the thesis submitted by Mr. Amir Ali Chandio thoroughly and found the whole work original and acceptable for the award of the degree of Doctorate in Political Science. To the best of my knowledge this work has not been submitted anywhere before for any degree. Supervisor Professor Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Choudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan Chairman Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan. ABSTRACT The nationalist feelings in Sindh existed long before the independence, during British rule. The Hur movement and movement of the separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency for the restoration of separate provincial status were the evidence’s of Sindhi nationalist thinking. -

Pakistan Elects a New President

ISAS Brief No. 292 – 2 August 2013 469A Bukit Timah Road #07-01, Tower Block, Singapore 259770 Tel: 6516 6179 / 6516 4239 Fax: 6776 7505 / 6314 5447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.isas.nus.edu.sg Pakistan Elects a New President Shahid Javed Burki1 Abstract With the election, on 30 July 2013, of Mamnoon Hussain as Pakistan’s next President, the country has completed the formal aspects of the transition to a democratic order. It has taken the country almost 66 years to reach this stage. As laid down in the Constitution of 1973, full executive authority is now in the hands of the prime minister who is responsible to the elected national assembly and will not hold power at the pleasure of the president. With the transition now complete, will the third-time Prime Minister, Nawaz Sharif, succeed in pulling the country out of the deep abyss into which it has fallen? Only time will provide a full answer to this question. Having won a decisive victory in the general election on 11 May 2013 and having been sworn into office on 5 June, Mian Mohammad Nawaz Sharif settled the matter of the presidency on 30 July. This office had acquired great importance in Pakistan’s political evolution. Sharif had problems with the men who had occupied this office during his first two terms as Prime Minister – in 1990-93 and 1997-99. He was anxious that this time around the 1 Mr Shahid Javed Burki is Visiting Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore. -

SA8000 Certified Facilities: As of June 30, 2015

SA8000 Certified Facilities: As of June 30, 2015 Date of 1st Name/ Addresses of Date of Initial recertificatio Date of 2nd Date of 3rd Date of 4th Certification internal CB Company Country Address Additional Sites Scope Industry Certification n recertification recertification recertification Body certificate ID D No. 2-142, Chinavutapalli Village- Gannavaram, Krishana District-Vijayawada - Manufacture & Export of ABS Quality 1947 INC. India Andhra Pradesh-India-521 286 -69-1- Leather products Leather 1-Oct-12 Evaluations 47609 67 Duy Tan Street, Hai Chau District, Manufacturing and 28 DA NANG JOINT Da Nang City, processing of garment STOCK COMPANY Vietnam Vietnam products Textiles 24-Jan-13 BSI SA 595078 3' MILLENNIUM via A. Bellatalla 1 56121 Pisa Ospedaletto Supply of local public TRAVEL S.R.L. Italy (PI) ITA transport and bus rental Transportation 27-Mar-14 CISE 585 30027-A01-02 SC PANDORA FASHION SRL 30027-A01 Company: 2 Ana Ipatescu Street 30027-A01-03 SC SIMIZ Tecuci, County Galati (37 km to HQ) FASHION SRL 30027-A01- 30027-A01 SC 30027-A01 Company: 73 Cuza Voda Street 02 : 6 Avantului Street, PANDORA PROD SRL- Focsani, County Vrancea(HQ) Focsani, County Vrancea – TECUCI,GALATI social site without activity ADDRESS 30027-A01-02 : 6 Avantului Street, Focsani, - Pandora Fashion 30027-A01 SC County Vrancea – social site without activity 30027-A01-02 Artera PANDORA PROD SRL- - Pandora Fashion Dj204d, Focsani, County FOSCAI,VRANCEA 30027-A01-02 Artera Dj204d, Focsani, Vrancea – manufacturing ADDRESS (HQ ) County Vrancea – manufacturing site - site - Pandora (2 km to 30027-A01-02 Pandora (2 km to HQ) HQ) SC PANDORA 30027-A01-03 : ARTERA DJ204D, 30027-A01-03 : ARTERA FASHION SRL FOSCANI,County VRANCEA DJ204D, FOSCANI,County 30027-A01-03 SC (2 km to HQ location) VRANCEA 30027-A01, 30027- SIMIZ FASHION SRL (2 km to HQ location) A01-02; 30027- Romania Textile Textiles 10-Dec-14 Intertek A01-03 Design, installation and maintenance electrical systems in medium and low via Arco della Ciambella, 13 - 00186 - Roma voltage - Maintenance Electrical 3M Elettrotecnica S.r.l. -

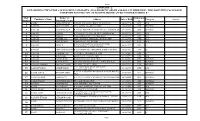

Candidate's Name Address Date of Birth Category 1 2 3

Sheet1 "ANNEXURE ‘A’ LIST SHOWING THE DETAILS OF ELIGIBLE CANDIDATES ( IN ALPHABETIC ORDER AND ROLL NUMBER WISE) WHO HAVE BEEN CALLED FOR INTERVIEW FOR THE POST OF PROCESS SERVER AS PER NOTIFIED SCHEDULE" Roll Father’ s/ Qualificatio Candidate’s Name Address Date of Birth Category Remarks Number Husband’s Name n 1 AABID KAMAAL KHAN SUNARI TEH TAURU DISTT MEWAT NUH 08/03/1995 10TH BCB 2 AADITYA SANJAY SINGH 2/298 AARYA NAAGR, SONIPAT 10/05/2002 12TH GENERAL 3 AAKASH RAJESH KUMAR H NO 723, KRISHNA NAGAR SEC 20A, FARIDABAD 07/18/1999 12TH GENERAL 4 AAKASH SAMPAT H NO 374 SEC 86 VILL. BUDENA FARIDABAD 08/03/1998 10TH BCB 5 AAKASH RAKESH VILL. BAROLI, SEC 80, FARIDABAD 01/02/1998 10TH BCA 6 AAKASH SUNDER LAL VILL GHARORA, TEH BALLABGRAH, FBD 08/12/1999 10TH BCA 7 AAKASH AJAY KUMAR ADARSH COLONY PALWAL 03/31/1997 B,SC BCA H NO D 396 WARD NO 12 NEAR PUNJABI AAKASH VIDHUR 06/07/1999 10TH SC 8 DHARAMSHALA, CAMP, PALWAL 9 AAKASH NIRANJAN KUMAR H NO 164 WAR NO 9 FIROZPUR JHIRKA, MEWAT 08/08/1995 12TH SC 10 AAKASH KUNWAR PAL VILL ARUA, CHANDAPUR, FBD 01/15/2001 10TH SC 11 AAKASH SURENDER KHATI PATTI, TIGAON, FBD 01/19/1999 12TH BCB 12 AAKASH GANGA RAM BHIKAM COLONY, BLB, FBD 05/25/2001 10TH GENERAL 13 AAKASH SHYAM DUTT 263 ARYA NAGAR, WAR NO 4 HODAL PALWAL 11/21/1997 10TH GENERAL 14 AAKASH SHARMA KISHAN CHAND 232 , HBC COLONY SIRSA 05/09/1989 12TH GENERAL VILL. -

2. Lt. Col (R) Ayub Khan Is Appointed As Minster of Counter Terrorism Punjab

1. General (retired) Raheel Sharif appointed as a chief of Saudi-led Islamic anti-terror alliance of 39th Muslim nations. 2. Lt. Col (R) Ayub Khan is appointed as minster of counter terrorism punjab. 3. Om Puri, Indian actor died on 6th january 2017. 4. Pakistan has successfully Test-Fires Submarine launched Babur-3 Missile in January 2017 with range of 450 km. 5. Utad Bade Fateh Ali Khan pakistani classical & Khyal Singer belongs to patiala family died in Islamabad on 4th January 2017. 6. Blakh sher badini, notorious commander and handler of social media of Baluchistan Liberation Army (BLA) surrender in January 2017. 7. Justice (retired), Saeeduzzaman siddiqui, 31st Governor of Sindh died on 11 January 2017. 8. PM Nawaz Sharif attended World Economic Forum Annual Meeting held between 17-20 January 2017 in Davos, Switzerland. 9. Balraj Manra, famous urdu Novelist of India died on 16TH January 2017. 10. Turkish Cargo Jet has crashed near Krgystan's manas airport on its way from Hong Kong to Istanbul, Airline ACT Airlines 11. Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy was Co chairing the 47th world economic forum Annual Meeting. She was the first pakistani to Co chair the Meeting. 12. China has handed Over 2 Navy Ships to Pakistan for Gwadar Security named after two rivers Hingol and Basol.Two more ships will be soon handed over named after Baluchistan Two districts DASHT and ZHOB. 13. The privatization Commission's board agreed Tuesday to a proposal to lease out Pakistan steel Mills (PSM) recommending that the length of the lease agreement be 30 years. -

Pakistan Assessment

PAKISTAN ASSESSMENT October 2000 Country Information and Policy Unit 1 CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY General 2.1 - 2.3 Languages 2.4 Economy 2.5 – 2.8 III HISTORY 1947-1978 3.1 – 3.4 1978-1988 3.5 – 3.8 1988-1993 3.9 – 3.15 1993-1997 3.16 – 3.27 1998-September 1999 3.28 – 3.40 October 1999 - October 2000 3.41– 3.45 IV INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE 4.1 POLITICAL SYSTEM Constitution 4.1.1 Government 4.1.2 – 4.1.7 Main Political Parties Following the Coup 4.1.8 – 4.1.12 President 4.1.13 Federal Legislature 4.1.14 – 4.1.15 Election Results 4.1.16 – 4.1.17 4.2 JUDICIAL SYSTEM Introduction 4.2.1 – 4.2.6 Court System 4.2.7 – 4.2.9 Special Courts 4.2.10 Federal Administered Tribal Areas 4.2.11 Anti-Terrorism Act 4.2.12 – 4.2.16 Sharia Law 4.2.17 – 4.2.24 1860 Pakistan Penal Code - Hadood Ordinances 4.2.25 – 4.2.26 - Qisas and Diyat Ordinances 4.2.27 – 4.2.28 - Blasphemy Law 4.2.29 – 4.2.34 - Death Penalty 4.2.35 – 4.2.39 Accountability Commission 4.2.40 – 4.2.43 National Accountability Bureau (NAB) 4.2.44 – 4.2.46 4.3 SECURITY General 4.3.1 – 4.3.3 Sindh 4.3.4 – 4.3.7 2 Punjab 4.3.8 V HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES 5.1 INTRODUCTION 5.1.1 – 5.1.3 5.2 GENERAL ASSESSMENT Findings of the UN Special Rapporteur 5.2.1 – 5.2.2 Police 5.2.3 – 5.2.7 Arbitrary Arrest 5.2.8 – 5.2.9 Torture 5.2.10 – 5.2.12 Human Rights Groups 5.2.13 – 5.2.15 5.3 SPECIFIC GROUPS Religious Minorities - Introduction 5.3.1 – 5.3.10 - Voting Rights 5.3.11 – 5.3.14 Ahmadis - Introduction 5.3.15 – 5.3.18 - Ahmadi Headquarters, Rabwah 5.3.19 - Legislative Restrictions 5.3.20