18. Is Progressive Education Obsolete? (Saturday Review)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploitation of the American Progressive Education Movement in Japan’S Postwar Education Reform, 1946-1950

Disarming the Nation, Disarming the Mind: Exploitation of the American Progressive Education Movement in Japan’s Postwar Education Reform, 1946-1950 Kevin Lin Advised by Dr. Talya Zemach-Bersin and Dr. Sarah LeBaron von Baeyer Education Studies Scholars Program Senior Capstone Project Yale University May 2019 i. CONTENTS Introduction 1 Part One. The Rise of Progressive Education 6 Part Two. Social Reconstructionists Aboard the USEM: Stoddard and Counts 12 Part Three. Empire Building in the Cold War 29 Conclusion 32 Bibliography 35 1 Introduction On February 26, 1946, five months after the end of World War II in Asia, a cohort of 27 esteemed American professionals from across the United States boarded two C-54 aircraft at Hamilton Field, a U.S. Air Force base near San Francisco. Following a stop in Honolulu to attend briefings with University of Hawaii faculty, the group was promptly jettisoned across the Pacific Ocean to war-torn Japan.1 Included in this cohort of Americans traveling to Japan was an overwhelming number of educators and educational professionals: among them were George S. Counts, a progressive educator and vice president of the American Federation Teachers’ (AFT) labor union and George D. Stoddard, state commissioner of education for New York and a member of the U.S. delegation to the first meeting of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).2,3 This group of American professionals was carefully curated by the State Department not only for their diversity of backgrounds but also for -

AS Vimed IROM SOCIOLOGICAL and PHILOSOPHICAL BASES

THE PE0BLES4 OF INDOCTRINATION: AS VimED IROM SOCIOLOGICAL AND PHILOSOPHICAL BASES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By MiOhio Nagai, B.A., A,M. The Ohio State University 1952 Approvi Adviser H. Gordon flullfish AClSilOWLEDGMiiMT It would be diriicult to express adequately my appreciation of the contributions made by many persons to this study. I first wish to express my gratitude to Dr. H. Gordon Hullfish, my adviser, wnose sincere guidance, generosity, and patience have led me from the first stage of learning in English in July, 194-9, up to the very last minute of completing this dissertation in May, 1952. I am very much indebted to Dr. Aurt H. Wolff whose wisdom and painstaking guidance have been of invaluable help in the writing of this dissertation. Likewise my indebtedness is due Dr. Alan E. Griffin and Dr. Lloyd Williams who read the complete manuscript and made numerous valuable corrections and suggestions. I also wish to express my appreciation for the intellectual stimulation gained for contacts with Dr. John W. Dennett and Mr. Iwao Ishino. Acknowledgment of a less specific, but not necessarily of less important value, is due Dr. Ervin E. Lewis whose kindness guided my first steps in this new land, finally, I wish to thank my wife, Mieko Nagai, without whose help this dissertation might not have been completed. MIGHIO NAGAI 909454 XI TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I INTRODUCTION.......................... 1 I Dictionary Definition.............................. 3 II The Indoctrination Controversy...... -

Progressive Education: Why It's Hard to Beat, but Also Hard to Find

Bank Street College of Education Educate Progressive Education in Context College History and Archives 2015 Progressive Education: Why it's Hard to Beat, But Also Hard to Find Alfie ohnK Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/progressive Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons, Educational Methods Commons, and the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Kohn, A. (2015). Progressive Education: Why it's Hard to Beat, But Also Hard to Find. Bank Street College of Education. Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/progressive/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the College History and Archives at Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in Progressive Education in Context by an authorized administrator of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Progressive Education Why It’s Hard to Beat, But Also Hard to Find By Alfie Kohn If progressive education doesn’t lend itself to a single fixed definition, that seems fitting in light of its reputation for resisting conformity and standardization. Any two educators who describe themselves as sympathetic to this tradition may well see it differently, or at least disagree about which features are the most important. Talk to enough progressive educators, in fact, and you’ll begin to notice certain paradoxes: Some people focus on the unique needs of individual students, while oth- ers invoke the importance of a community of learners; some describe learning as a process, more journey than destination, while others believe that tasks should result in authentic products that can be shared.[1] What It Is Despite such variations, there are enough elements on which most of us can agree so that a common core of progressive education emerges, however hazily. -

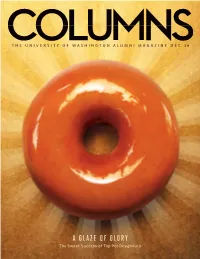

A GLAZE of GLORY the Sweet Success of Top Pot Doughnuts JOIN US ANY TIME, EVERYWHERE

THE UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON ALUMNI MAGAZINE DEC 1 4 A GLAZE OF GLORY The Sweet Success of Top Pot Doughnuts JOIN US ANY TIME, EVERYWHERE 20 ADVANCED DEGREES + 50 CERTIFICATES + 100S OF COURSES AEROSPACE ENGINEERING // PUBLIC HEALTH // C# // APPLICATION DEVELOPMENT BIOSTATISTICS // COMPUTATIONAL FINANCE // MANAGEMENT // PROGRAMMING BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION // BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT // INFORMATION SECURITY ANALYTICS // GIS // DATA VISUALIZATION // SUSTAINABLE TRANSPORTATION RUBY // RISK MANAGEMENT // BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE // INFORMATION SYSTEMS PROJECT MANAGEMENT // CONTENT STRATEGY // ORACLE DATABASE ADMIN LOCALIZATION // PARALEGAL // MACHINE LEARNING // SUPPLY CHAIN LOGISTICS BEHAVIORAL HEALTH // GERONTOLOGY // BIOTECHNOLOGY // CIVIL ENGINEERING DEVOPS // DATA SCIENCE // MECHANICAL ENGINEERING // HEALTH CARE // HTML CONTENT STRATEGY // EDUCATION // PROJECT MANAGEMENT // INFORMATICS STATISTICAL ANALYSIS // E-LEARNING // CLOUD DATA MANAGEMENT // EDITING C++ // INFRASTRUCTURE PLANNING // LEADERSHIP // BIOSCIENCE // LINGUISTICS INFORMATION SCIENCE // AERONAUTICS & ASTRONAUTICS // APPLIED MATHEMATICS CONSTRUCTION ENGINEERING // GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEMS // PYTHON UW ONLINE 2 COLUMNS MAGAZINE ONLINE.UW.EDU JOIN US ANY TIME, EVERYWHERE 20 ADVANCED DEGREES + 50 CERTIFICATES + 100S OF COURSES AEROSPACE ENGINEERING // PUBLIC HEALTH // C# // APPLICATION DEVELOPMENT BIOSTATISTICS // COMPUTATIONAL FINANCE // MANAGEMENT // PROGRAMMING BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION // BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT // INFORMATION SECURITY ANALYTICS // GIS // DATA VISUALIZATION // -

Critical Education

Critical Education Volume 7 Number 4 March 1, 2016 ISSN 1920-4125 Reconstruction of the Fables The Myth of Education for Democracy, Social Reconstruction and Education for Democratic Citizenship Todd S. Hawley Kent State University Andrew L. Hostetler Peabody College at Vanderbilt University Evan Mooney Montclair State University Citation: Hawley T. S., Hostetler, A. L., & Mooney, E. (2016). Reconstruction of the fables: The myth of education for democracy, social reconstruction and education for democratic citizenship. Critical Education, 7(4). Retrieved from http://ojs.library.ubc.ca/index.php/criticaled/article/view/186116 Abstract A central goal of social studies education is to prepare students for citizenship in a democracy. Further, trends in the social, political, and economic circumstances, currently and historically in American education and society broadly suggest that: 1) a need for change exists, 2) that change is possible and can be brought about through a reconsideration of social reconstructionist ideas and values, especially those espoused by George Counts, and 3) that social studies teachers and teacher educators can work toward this change through educational practices. In this paper, we argue for these three points through a critical discussion of a perpetuated myth of democratic education. Readers are free to copy, display, and distribute this article, as long as the work is attributed to the author(s) and Critical Education, it is distributed for non-commercial purposes only, and no alteration or transformation is made in the work. More details of this Creative Commons license are available from http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. All other uses must be approved by the author(s) or Critical Education. -

John Dewey and the Beginnings of Progressive Early Education in Hawai‘I Alfred L

John Dewey in Hawai‘i 23 John Dewey and the Beginnings of Progressive Early Education in Hawai‘i Alfred L. Castle Hawai‘i has often been the beneficiary of the insights of reality called “practice” while reserving the higher order extraordinary men and women who visited the islands “theory” for the transcendent, changeless divine realm. and made important observations. Among these was Mystery and glamour attached to the eternal, sempiternal perhaps America’s most famous philosopher, John Dewey realm, while the material or “practical” realm was (1859-1952). First visiting Honolulu in 1899 as the guest deemed inferior. The separation of the two conceptual of Mary Tenney Castle and her family, Dewey would help orders was mirrored in the distinction between practice establish Hawai‘i’s first progressive kindergartens while and theory. This isolation of theory and practice has, in also assisting in the establishment of the new progressive Dewey’s estimation, held mankind back for centuries. Castle Kindergarten on King Street. Dewey was a close The devaluing of the natural realm of the changing friend of his University of Chicago colleague and symbolic and flawed mundane world was regnant, according to interactionist George Herbert Mead and his wife Helen Dewey, until the early modern period when Galileo, Castle. He had met the late Henry Castle, a young Newton, and Bacon began the slow process of taking philosopher whose life had been cut short in a shipping the natural world as worthy of precise quantitative accident on the North Sea, in 1895. Dewey’s visit coincided interpretation. Over time, science rid itself of the last with the incipient efforts of educators to formulate a radical vestiges of the illusory search for ultimate, invariable re-engineering of early education, which would forever reality and became more secure with experimentalism change the way the public looked at young children and and operationalism. -

Social Studies and the Social Order: Transmission Or Transformation?

Research and Practice “Research & Practice,” established early in 2001, features educational research that is directly relevant to the work of classroom teachers. Here, Social Studies and I invited William Stanley to bring a historical perspective to the peren- nial question, “Should social studies the Social Order: teachers work to transmit the status quo or to transform it?” Transmission or —Walter C. Parker, “Research and Practice” Editor, University of Transformation? Washington, Seattle. William B. Stanley Should social studies educators The Quest for Democracy and schools are places where chil- transmit or transform the social order? Debates over education reform take dren receive formal training as citizens. By “transform” I do not mean the com- place within a powerful historical and Democracy is also a process or form mon view that education should make cultural context. In the United States, of life rather than a fixed end in itself, society better (e.g., lead to scientific schooling is generally understood as and we should regard any democratic breakthroughs, eradicate disease, and an integral component of a democratic society as a work in progress.1 Thus, increase productivity). Rather, I am society. To the extent we are a demo- democratic society is something we are referring to approaches to education cratic society, one could argue that edu- always trying simultaneously to main- that are critical of the dominant social cation for social transformation could tain and reconstruct, and education is order and motivated by a desire to be anti-democratic, a view held by essential to this process. ensure both political and economic many conservatives. -

Download File

1 Teacher Voice Jonathan Gyurko Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 2 © 2012 Jonathan Gyurko All rights reserved ABSTRACT Teacher Voice Jonathan Gyurko In many of today’s education debates, “teacher voice” is invoked as a remedy to, or the cause of, the problems facing public schools. Advocates argue that teachers don’t have a sufficient voice in setting educational policy and decision-making while critics maintain that teachers have too strong an influence. This study aims to bring some clarity to the contested and often ill-defined notion of “teacher voice.” I begin with an original analytical framework to establish a working definition of teacher voice and a means by which to study teachers’ educational, employment, and policy voice, as expressed individually and collectively, to their colleagues, supervisors, and policymakers. I then use this framework in Part I of my paper which is a historical review of the development and expression of teacher voice over five major periods in the history of public education in the United States, dating from the colonial era through today. Based on this historical interpretation and recent empirical research, I estimate the impact of teacher voice on two outcomes of interest: student achievement and teacher working conditions. In Part II of the paper, I conduct an original quantitative study of teacher voice, designed along the lines of my analytical framework, with particular attention to the relationship between teacher voice and teacher turnover, or “exit.” As presented in Parts I and II and summarized in my Conclusion, teacher voice requires an enabling context. -

Countering the Neos: Dewey and a Democratic Ethos in Teacher Education

Countering the Neos Dewey and a Democratic Ethos in Teacher Education Jamie C. Atkinson (University of Georgia) Abstract Neoliberalism and neoconservatism are two ideologies that currently plague education. The individualistic free- market ideology of neoliberalism and the unbridled nationalistic exceptionalism associated with neo- conservatism often breed a narrowed, overstandardized curriculum and a hyper- testing environment that discourage critical intellectual practice and democratic ideas. Dewey’s philosophy of education indicates that he understood that education is political and can be undemocratic. Dewey’s holistic pragmatism, combined with aspects of social reconstructionism, called for a philosophical movement that favors democratic school- ing. This paper defines neoliberal and neoconservative ideologies and makes a case for including more cri- tique within teacher preparation programs, what Dewey and other educationists referred to as developing a significant social intelligence in teachers. Critical studies embedded within teacher education programs are best positioned to counter the undemocratic forces prevalent in the ideologies of neoliberalism and neocon- servatism. My conclusions rely on Dewey’s philosophy from his work Democracy and Education. Submit a response to this article Submit online at democracyeducationjournal .org/ home Read responses to this article online http:// democracyeducationjournal .org/ home/ vol25/ iss2/ 2 We are living in times when private and public aims and policies are at the direction of our country and our educational systems. During strife with each other. The sum of the matter is that the times are various periods, tensions over the nature, structure, and direction out of joint, and that teachers cannot escape even if they would, some of education have increased in response to ideological and socio- responsibility for a share in putting them right. -

Characteristics of Contemporary U. S. Progressive Middle Schools

CHARACTERISTICS OF CONTEMPORARY U. S. PROGRESSIVE MIDDLE SCHOOLS JAN WARE RUSSELL A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Ph.D. in Leadership and Change Program of Antioch University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October, 2012 This is to certify that the Dissertation entitled: CHARACTERISTICS OF CONTEMPORARY U.S. PROGRESSIVE MIDDLE SCHOOLS prepared by Jan Ware Russell Is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Leadership and Change. Approved by: ______________________________________________________________________________ Carol Baron, Ph.D., Chair date ______________________________________________________________________________ Elizabeth Holloway, Ph. D., Committee Member date ______________________________________________________________________________ Charis Sharp, Ph. D., Committee Member date ______________________________________________________________________________ Jane Miller, Ed. D., External Reader date Copyright 2012 Jan Ware Russell All rights reserved Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to the faculty of the Antioch University, Leadership and Change program. My doctoral journey could not have been accomplished without each faculty member’s input along the way. I would like to offer my special thanks to Dr. Laurien Alexandre (Program Director) and Dr. Al Guskin (President Emeritus) for their pioneering spirit that birthed this program. Their continued passion for the progressive philosophies—student-centered learning, community integration, and democratic decision- making—that are a model of the learning environment explored in this dissertation. I am grateful to Dr. Mitch Kusy who conducted my screening interview. His humor coupled with his business-like manner quickly put me at ease allowing me to ask and have answers to ALL my questions. I am particularly grateful to my first faculty advisor, Dr. -

The Impact of COVID-19 on Young Children's Education - Exploring the Compatibility of Combining Progressive Education with Online Learning

Sarah Lawrence College DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence Child Development Theses Child Development Graduate Program 5-2021 The Impact of COVID-19 on Young Children's Education - Exploring the Compatibility of Combining Progressive Education with Online Learning Yini Li Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.slc.edu/child_development_etd Part of the Early Childhood Education Commons, and the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Li, Yini, "The Impact of COVID-19 on Young Children's Education - Exploring the Compatibility of Combining Progressive Education with Online Learning" (2021). Child Development Theses. 46. https://digitalcommons.slc.edu/child_development_etd/46 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Child Development Graduate Program at DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Child Development Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON YOUNG CHILDREN’S EDUCATION—EXPLORING THE COMPATIBILITY OF COMBINING PROGRESSIVE EDUCATION WITH ONLINE LEARNING Yini Li MAY 2021 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Child Development Sarah Lawrence College i ABSTRACT The COVID-19 outbreak at the end of 2019 forced most schools around the world to move their classrooms online. This research takes the progressive education of young children as the basic educational concept and attempts to explore the compatibility of online education and progressive education of young children through interviews with educators in the United States and China. By understanding how online teaching occurred through interviews with early childhood teachers who implemented it during the COVID-19 outbreak, and the decisions and opinions of school administrators, this study compares the different teaching measures taken by early childhood teachers in the United States and China in the face of the COVID-19 outbreak. -

Progressive Education in Black High Schools

Progressive Education in Black High Schools The Secondary School Study, 1940–1946 Progressive Education in Black High Schools The Secondary School Study, 1940–1946 Craig Kridel Dedication To William A. Robinson, William H. Brown, and Secondary School Study teachers who, through their faith in experimentation and belief in pro- gressive education methods, sought to build school communities that were more compassionate, more generous, more humane, and more thoughtful. To those compassionate, generous, humane, and thoughtful Secondary School Study teachers and students who participated in this Museum of Education research project. Progressive Education in Black High Schools The Secondary School Study, 1940–1946 Craig Kridel Museum of Education University of South Carolina Museum of Education Wardlaw Hall University of South Carolina Columbia, SC 29208 www.ed.sc.edu/museum www.museumofeducation.info a financially-supported research unit of the College of Education and an institutional member of the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience The Secondary School Study Exhibition www.ed.sc.edu/museum/second_study.html www.museumofeducation.info/sss This limited edition exhibition catalog is published to commemorate the seventh-fifth anniversary of the Secondary School Study. with support provided by the spencer foundation AND THE DANIEL TANNER FOUNDaTION All rights reserved. No part of this catalog may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission of the author, except by a reviewer or researcher who may quote passages for scholarly purposes. © 2015 Craig Kridel Design: BellRose Studio Published in Columbia, South Carolina ISBN 978-0-692-55579-8 Manufactured in the United States of America Contents Preface vii Understanding Experimentation in 1940s Black High Schools 2 Secondary School Study Vignettes Atlanta University Laboratory School, Atlanta, Georgia 23 Booker T.