New Ajem 1210

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Varanus Doreanus) in Australia

BIAWAK Journal of Varanid Biology and Husbandry Volume 11 Number 1 ISSN: 1936-296X On the Cover: Varanus douarrha The individuals depicted on the cover and inset of this issue represent a recently redescribed species of monitor lizard, Varanus douarrha (Lesson, 1830), which origi- nates from New Ireland, in the Bismark Archipelago of Papua New Guinea. Although originally discovered and described by René Lesson in 1830, the holotype was lost on its way to France when the ship it was traveling on became shipwrecked at the Cape of Good Hope. Since then, without a holotype for comparitive studies, it has been assumed that the monitors on New Ireland repre- sented V. indicus or V. finschi. Recent field investiga- tions by Valter Weijola in New Ireland and the Bismark Archipelago and phylogenetic analyses of recently col- lected specimens have reaffirmed Lesson’s original clas- sification of this animal as a distinct species. The V. douarrha depicted here were photographed by Valter Weijola on 17 July and 9 August 2012 near Fis- soa on the northern coast of New Ireland. Both individu- als were found basking in coconut groves close to the beach. Reference: Weijola, V., F. Kraus, V. Vahtera, C. Lindqvist & S.C. Donnellan. 2017. Reinstatement of Varanus douarrha Lesson, 1830 as a valid species with comments on the zoogeography of monitor lizards (Squamata: Varanidae) in the Bismarck Archipelago, Papua New Guinea. Australian Journal of Zoology 64(6): 434–451. BIAWAK Journal of Varanid Biology and Husbandry Editor Editorial Review ROBERT W. MENDYK BERND EIDENMÜLLER Department of Herpetology Frankfurt, DE Smithsonian National Zoological Park [email protected] 3001 Connecticut Avenue NW Washington, DC 20008, US RUSTON W. -

Dr Peter Hunt

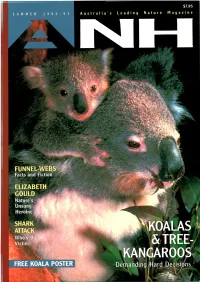

Australian Quality Awards Foundation You'llfind Caltex behind each one of these doors. These projects in the field of academic excellence in the stamp their mark in the world. education are some of the many National Scholarship for Women, And that's that Caltex supports for today's to the nurturing ofbusiness talents important if young Australians. in the Young Achievers, Caltex is we're to achieve From the encouragement of giving Australians the chance to our full potential. COMMITTED TO AUSTRALIA'S FUTURE LBC'M CCA 0015 Up Front Koalas and tree-kangaroos often exist in small, isolated colonies with greatly fluctuating populations. Now that their numbers are no longer curtailed by hunting, some colonies are faced with serious overpopulation problems. Unfortunately managing them isn't as simple as relocating colonies, so conservation managers face some tough decisions. Which spiders do you fear most? Odds on it's funnel-webs. Do you stomp on your shoes before :, :,;: z < inserting your foot or carefully check the bottom of �-..,, � ':- ....... � the pool in case one lurks there? These spiders are � 3 often accredited with legendary powers, so we sent < V funnel-web expert Mike Gray on a myth-breaking mission. Working directly across the corridor from him has its moments, as sometimes on particularly hot days, Mike has cooled off his heat stressed subjects by putting them in our fridge! Another summertime paranoia is the fear of sharks. These maligned creatures are detested and feared by people, yet we are more likely to be killed by a lightning strike than a shark! Indeed, people are a greater threat to sharks-for every person killed by a shark over 23 million kilograms of sharks and rays are killed by people. -

Climate Change and Queensland Biodiversity

Climate Change and Queensland Biodiversity An independent report commissioned by the Department of Environment and Resource Management (Qld) Tim Low © Author: Tim Low Date: March 2011 Citation: Low T. (2011) Climate Change and Terrestrial Biodiversity in Queensland. Department of Environment and Resource Management, Queensland Government, Brisbane. On the Cover: The purple-necked rock wallaby (Petrogale purpureicollis) inhabits a very rocky region – the North-West Highlands – where survival during heatwaves and droughts depends on access to shady rock shelters. Rising temperatures will render many of their smaller shade refuges unusuable. Photo: Brett Taylor Paperbarks (Melaleuca leucadendra) are the trees at most risk from sea level rise, because they are habitat dominants on recently formed plains near the sea where freshwater settles. They were probably scarce when the sea fell during glacials, and tend to support less biodiversity than older forest types. Photo: Jeanette Kemp, DERM Contents 1. Introduction and summary 1 5. Ecological framework 52 1.1 Introduction 1 5.1 The evidence base 53 1.2 Summary 4 5.1.1 Climatically incoherent distributions 53 1.3 Acknowledgements 5 5.1.2 Introduced species distributions 56 5.1.3 Experimental evidence 58 2. Climate change past and future 7 5.1.4 Genetic evidence 58 5.1.5 Fossil evidence 58 2.1 Temperature 8 5.2 Why distributions might not reflect climate 59 2.1.1 Past temperatures 9 5.2.1 Physical constraints 60 2.2 Rainfall 10 5.2.2 Fire 62 2.2.1 Past rainfall 11 5.2.3 Limited dispersal 63 2.3 Drought 12 5.2.4 Evolutionary history 65 2.3.1 Past drought 12 5.2.5 Lack of facilitation 65 2.4 Cyclones 12 5.2.6 Competition 66 2.4.1 Past cyclones 12 5.2.7 Predators and pathogens 70 2.5 Fire 13 5.3 Discussion 71 2.5.1 Past fire 13 5.3.1 High altitude species 71 2.6 Sea level rise 14 5.3.2 Other species 73 2.6.1 Past sea level rise 14 5.4 Management consequences 74 3. -

AUSTRALIA– Country Data Dossier for Protected Areas Summary Sheet

Country data dossier for protected areas AUSTRALIA– Country Data Dossier for Protected Areas Summary Sheet Estimated current PA coverage (Source: DOPA, see footnote on next page) 14.61% Terrestrial (1 126 825 km2) 39.47% Marine (3 267 871 km2) Terrestrial and Marine Ecoregions Out of 41 terrestrial ecological regions: 14 ecological regions (Mitchell grass downs, Western Australian Mulga shrublands, Tirari-Sturt stony desert, Carpentaria tropical savanna, Kimberly tropical savanna, Brigalow tropical savanna, Southeast Australia temperate savanna, Eastern Australia mulga shrublands, Victoria Plains tropical savanna, Pilbara shrublands, Southwest Australia savanna, Einasleigh upland savanna, Carnarvon xeric shrublands, Mount Lofty woodlands) are the highest priority candidate sites for further protection. Out of 23 marine ecological regions: 2 ecological regions (Bassian, Cape Howe) are the highest priority candidate sites for further protection. Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBAs) Australia has 309 IBAs: 71 IBAs have no protection, 152 IBAs have partial protection and 86 IBAs have complete protection. Bringing some IBAs that have no protection or having partial protection under protected areas and improving the management effectiveness of all IBA PAs are priority actions. Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBAs) in Danger Out of the 4 IBAs in danger impacted by fire and fire suppression, residential and commercial development, and agriculture/aquaculture, 2 IBAs have little or no protection. Although 1 IBA is mostly protected and 1 IBA is fully protected, they face a number of threats. Bringing unprotected IBAs under protection either by expanding existing PAs or establishing new PAs and improving management effectiveness through addressing threats are potential further actions. Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites (AZEs) Australia has 17 AZEs: 2 AZEs have no protection, 2 AZEs have partial protection and 13 AZEs have complete protection. -

Cape York in the Wet

VOL. 13 (7) SEPTEMBER 1990 209 AUSTRALIAN BIRD WATCHER 1990, 13, 209-217 Cape York in the Wet by GORDON BERULDSEN, Cape York Bird Weeks, PD. Box 387, Kenmore, Queensland 4069 Although there have been several studies of the birds of Cape York Peninsula (Barnard 1911, Thomson 1935, Mack 1953, Officer 1967, Kikkawa 1976) there is little information from the wet season. I have now had the opportunity of visiting Cape York six times between 1986 and 1989 and here record some of my experiences and the more interesting observations. I do not propose in this paper to list all species observed, just those that I found of particular interest. More detail will follow in a later article. Habitats Between the course of the Jardine River that runs across the Cape from east to west, and Jackey Jackey on the east coast, north to The Tip, there exists a surprising variety of habitats. Even the open forests vary widely in form, content and structure. Habitats range from a wide variety of open forests to heathlands, fresh-water lakes, swamps and streams, salt-water estuaries, monsoon scrubs and forests, including several locations with a stand of tree ferns. There is open grassland around Bamaga (Jackey Jackey) airport and a few other locations. Beaches and wide tidal flats are backed by monsoon forests or casuarina scrub or mangroves. Rocky headlands support low shrubbery in exposed situations and low monsoon scrub in sheltered areas. There are a few small areas of low coastal scrub, similar in appearance to southern coastal heath (Kikkawa 1976). -

Mcintyre-Tamwoy, Susan (2000) Red Devils and White Men

This file is part of the following reference: McIntyre-Tamwoy, Susan (2000) Red devils and white men. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/8183 PART II ________________________________________ THE STORI BLO MEINLAN Plate 4: Harbour of Somerset, Qld September 21st 1872: Watercolour by unknown artist looking out towards Albany Island. (Courtesy of the Mitchell Library, NSW. Original held in the Small Picture Collection DG*D3 folio2) 70 Chapter 5: ________________________________________ DISKAINTAIM 5.1 The Fourth Coming We watched the marakai as she rolled up her swag and gathered her belongings. Any minute now and she would realise they were missing! Yes - There now. It wasn’t the same if they didn’t feel the loss. There was still a chance though that we would have to give them up. She was with two men of the people. But we did not recognize them and they did not appear to know us. The rules were that unless they spoke the words we could keep the prize. We were going to win, we could feel it! Last night we had crowded around to listen, just outside the light of their campfire. The new tongue that the marakai spoke was harsh to our ears and hard to understand. We learnt that she had come to study the land, our place that they call Somerset. She has come to learn and observe but she did not see us as we crowded close to claim our prize. We had no doubt that she would be like all marakai, arrogant and deaf to the language of the land. -

Ampuyu*) YADHAIGANA ANGGAMUDI Fruit Bat Falls (E.G

Thursday Island Horn I. k POLICE MURALAG 12 Cape York Prince of Wales I. Legend Golden Shouldered Parrot Seisia Lockerbie Scrub rainforest 13 Newcastle Bay Umagico New Mapoon Roads Tenure This savanna specialist is endangered Injinoo Bamaga minor National Park and found nowhere else. Once wide- 7 Ak POLICE major Mining Lease spread across the southern Peninsula, the JACKY JACKY CK sealed Golden-shouldered Parrot is now only Fuel available found in two small areas. They nest in Photo: Scott Templeton Scott Photo: YADHAIGANA Camping with facilities. termite mounds in the savanna country. Old Telegraph Track (Many bush camping areas also exist.) JARDINE RIVER Lotus Bird Lodge takes birdwatchers k Hospital or medical A Airport Bamaga Rd to see them on places such as Artemis 9 Number of business. station near Musgrave. Jardine River (Corresponds with text and contact details on the back of this map.) National Park RS Ranger station. (Named except where name corresponds with National Park.) Cuscus Eliot/Twin Falls TRIBAL OR LANGUAGE OR CLAN GROUP (Ampuyu*) YADHAIGANA ANGGAMUDI Fruit Bat Falls (e.g. ) Bam Old Telegraph Track Tribal or language or nation groups, as reported by Horton (2000) This strange and beautiful nocturnal aga R with some additional local knowlege. The Horton (2000) map covered d Captain Billy’s Landing possum is a rainforest specialist, found all of Australia and was the result of six years research by the Australian Heathlands Resource Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Islander Studies. The map is general only in New Guinea and Cape York Reserve and only depicts larger groups, within which clans and local dialects Peninsula. -

Review of the Management of Feral Animals and Their Impact on Biodiversity in the Rangelands

Pest Animal Control CRC Review of the management of feral animals and their impact on biodiversity in the Rangelands A resource to aid NRM planning PAC CRC Report June 2005 Andrew Norris Pest Animal Control Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra Tim Low Consultant, Brisbane Iain Gordon CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, Townsville Glen Saunders NSW Department of Primary Industries, Orange Steven Lapidge Pest Animal Control Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra Keryn Lapidge Pest Animal Control Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra Tony Peacock Pest Animal Control Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra Roger Pech CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra Review of the management of feral animals and their impact on biodiversity in the Rangelands A resource to aid NRM planning PAC CRC Report June 2005 A report to the Australian Government Department of the Environment and Heritage prepared by the Pest Animal Control Cooperative Research Centre Contributors Andrew Norris Pest Animal Control Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra Tim Low Consultant, Brisbane Iain Gordon CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, Townsville Glen Saunders NSW Department of Primary Industries, Orange Steven Lapidge Pest Animal Control Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra Keryn Lapidge Pest Animal Control Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra Tony Peacock Pest Animal Control Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra Roger Pech CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra Suggested Citation Norris, A, and Low, T, 2005, Review of the management of feral animals and their impact on biodiversity in the Rangelands: A resource to aid NRM planning, Pest Animal Control CRC Report 2005, Pest Animal Control CRC, Canberra COPYRIGHT AND DISCLAIMERS © Commonwealth of Australia Information contained in this publication may be copied or reproduced for study, research, information or educational purposes, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgement of this source. -

Biotic Interactions Mediate the Influence of Bird Colonies on Vegetation and Soil Chemistry at Aggregation Sites

Ecology, 98(2), 2017, pp. 382–392 © 2016 by the Ecological Society of America Biotic interactions mediate the influence of bird colonies on vegetation and soil chemistry at aggregation sites DANIEL JAMES DEANS NATUSCH,1,3 JESSICA ANN LYONS,2 GREGORY P. BROWN,1 AND RICHARD SHINE1 1School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales 2006 Australia 2Resource Evaluation and Development, Australia Abstract. Colonial- nesting organisms can strongly alter the chemical and biotic conditions around their aggregation sites, with cascading impacts on other components of the ecosystem. In tropical Australia, Metallic Starlings (Aplonis metallica) nest in large colonies far above the forest canopy, in emergent trees. The ground beneath those trees is open, in stark contrast to the dense foliage all around. We surveyed the areas beneath 27 colony trees (and nearby ran- domly chosen trees lacking bird colonies) to quantify the birds’ impacts on soil and vegetation characteristics, and to test alternative hypotheses about the proximate mechanisms responsible for the lack of live vegetation beneath colony trees. Nutrient levels were greatly elevated beneath colony trees (especially, those with larger colonies), potentially reaching levels toxic to older trees. However, seedlings thrived in the soil from beneath colony trees. The primary mechanism generating open areas beneath colony trees is disturbance by scavengers (feral pigs and native Turkeys) that are attracted in vast numbers to these nutrient hotspots. Seedlings flourished within exclosures inaccessible to vertebrate herbivores, but were rapidly consumed if unprotected. Our results contrast with previous studies of colonies of seabirds on remote islands, where a lack of large terrestrial herbivores results in bird colonies encouraging rather than eliminating vegetation in areas close to the nesting site. -

UGAR ISLAND January 2013

PROFILE FOR MANAGEMENT OF THE HABITATS AND RELATED ECOLOGICAL AND CULTURAL RESOURCE VALUES OF UGAR ISLAND January 2013 Prepared by 3D Environmental for Torres Strait Regional Authority Land & Sea Management Unit Cover image: 3D Environmental (2013) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Ugar (Stephens) Island is a small and remote island that occupies a total area of 36 hectares located 160 kilometers north east of Thursday Island. The island is formed on a platform of massively bedded basalt, up to 30m high, that is the result of Pleistocene age volcanic activity, and is part of the Eastern Group of Torres Strait Islands which includes Mer (Murray) and Erub (Darnley) and a number of small uninhabited islands and sand cays. It is fringed by coral reef with its shoreline surrounded by numerous fish traps constructed using basalt rock boulders. The vegetation on Ugar is simple and dominated by a unique vine forest association, which has been impacted by generations of human land use and more recent clearing for infrastructure. Intact vine forest forms approximately 30% of the islands’ vegetation cover, persisting on sheltered slopes and escarpments that have escaped clearing. Other vegetation types include mangrove forest on the island margins and extensive areas of altered forest habitat. Two natural broad vegetation groups comprising two vegetation communities and two regional ecosystems exist on the island. Whilst limited in distribution, the vine thicket habitat is endemic to the Torres Strait Eastern Island Group, and has no representation elsewhere in Queensland. The total known flora of 195 species comprises 116 native species and 79 naturalised species. The latter accounts for 41 % of the islands flora which is the highest of any of the inhabited islands surveyed in the Torres Strait region and testament to the level of disturbance. -

1928 CRC Report Rainforest.Indd

The Rainforests of Cape York Peninsula 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background The subject of this report is work carried out by the authors between 15 October 1992 and 1 August 1994. One of us, David Fell, was dedicated entirely to the project during that time with heavy responsibilities for data collection and processing of data and botanical material collected on field trips, among other duties. Peter Stanton took responsibility for design of the project and supervision and participated in the majority of the field trips; although heavily involved for much of the time in unrelated work. The project was, however, flexible in design and practice, so that the nature of each stage depended heavily on experience and observation to that point. This iterative process, and the nature of our work relationship, has ensured that this final report is, intellectually, the product of both of us to equal degree. The National Rainforest Conservation Strategy of the Commonwealth Government largely funded the work, with matching contributions by the Queensland Government. It was however, a significant contributor to the vegetation mapping and description carried out by V. J. Neldner and J. R. Clarkson within Stage 1 of the Cape York Peninsula Land Use Strategy (CYPLUS)2. Site data were initially analysed by P. J. Lethbridge as part of a Queensland Environmental Protection Agency report on the CYPLUS work and have contributed to an analysis of National Estate values of Cape York Peninsula by the Australian Heritage Commission3. In the sense that the data from the work have now been (a) entered into the appropriate data bases; (b) contributed to the production of a vegetation map of Cape York Peninsula; and (c) used for analyses of the conservation status and management of the various plant communities of the Peninsula; it is considered that the original scientific imperatives of the work have largely been fulfilled. -

The Vegetation and Flora of Mabuyag, Torres Strait, Queensland

Memoirs of the Queensland Museum | Culture Volume 8 Part 1 Goemulgaw Lagal: Natural and Cultural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait. Edited by Ian J. McNiven and Garrick Hitchcock Minister: Annastacia Palaszczuk MP, Premier and Minister for the Arts CEO: Suzanne Miller, BSc(Hons), PhD, FGS, FMinSoc, FAIMM, FGSA , FRSSA Editor in Chief: J.N.A. Hooper, PhD Editors: Ian J. McNiven PhD and Garrick Hitchcock, BA (Hons) PhD(QLD) FLS FRGS Issue Editors: Geraldine Mate, PhD PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD 2015 © Queensland Museum PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone: +61 (0) 7 3840 7555 Fax: +61 (0) 7 3846 1226 Web: qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 VOLUME 8 IS COMPLETE IN 2 PARTS COVER Image on book cover: People tending to a ground oven (umai) at Nayedh, Bau village, Mabuyag, 1921. Photographed by Frank Hurley (National Library of Australia: pic-vn3314129-v). NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the CEO. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed on the Queensland Museum website qm.qld.gov.au A Queensland Government Project Design and Layout: Tanya Edbrooke, Queensland Museum Printed by Watson, Ferguson & Company The vegetation and flora of Mabuyag, Torres Strait, Queensland David G.