Three Reincarnations of the Smilin' Buddha Cabaret

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1975-1978-File-DERA

c~ t ~ BOWi Otl IA f iiJ - -----~R~E~C~E~l~V:;,.:E~O~ f----*~*-:--*-;----- - ------:N:UM=BE:R~-9~ f t A PR IL t97tl Committee avors spending $2.7 million for sites t:y IIA\'D\. 1;u ,1 Ell .\ 1ornr l'Om111Jtll'C or «·•Jtmcil h.i.'i rct.-om ·n,c mofiun lo spend tl 7 n1111ion for Tht· moI I011 \l,1s Tl., S2-7 million i• a prtion or he S6 rucnd1"1 th.1l $2 7 nulfi,.n he ~IM·nl n11 iW bt>Usmg was passed "-3 m the t..-omnullcc. )(1J1por1Ptf h~· AICX'rUK'II I l;irry H:tnkm. million rhe- pro\inc:-ia l govC'rnme,nt p,.1d q,unng !',IICS for hou.,mi; rn Jiu.• <lou·nton n ~ 11h AJdumcn J .1Ck Volnd,. Ed Swee11t'Y :\hkl' 11:ir<"Ourl. ,\rt Co"1t! and Helen for lhc ,'UurthocJ~· nc,t lo fh,, ouli~ &Ja c,1-J.,,d~ :irca. and Hugh Bird opposed. ' 1111.\('\' t,on on .\1:1in. • I _Phillips to Oppose Hous1ng · Local Groups Urge Eriksen Dollars for Downtown East to Reconsider By JEAN SWANSON L. E.A. P. BRUCE ERIKSEN, Mar. 14/75. Mayor Phi llips will oppose ions and Aldermen Rankin and nasium and parking l ot for / RE : YOUR RESIGNATION - the recommendation of a Harcourt. It was noted that policemen. Alderman Harcou rt' , We, the undersigned ask you joint COIDIDittee of council over 1, 000 housi ng units had s aid he would like to use , to reconsider your decision; to use $2. -

Anal Cunt • Deceased • Executioner Fistula • Panzerbastard • Psycho Rampant Decay/Kruds • Rawhide Revilers • Slimy Cunt & the Fistfucks Strong Intention

PRESENTS RELEASES FROM: ANAL CUNT • DECEASED • EXECUTIONER FISTULA • PANZERBASTARD • PSYCHO RAMPANT DECAY/KRUDS • RAWHIDE REVILERS • SLIMY CUNT & THE FISTFUCKS STRONG INTENTION Now Exclusively Distributed by ANAL CUNT Street Date: Fuckin’ A, CD AVAILABLE NOW! INFORMATION: Artist Hometown: Boston, MA Key Markets: Boston, New York, Los Angeles, Portland OR For Fans of: GG ALLIN, NAPALM DEATH, VENOM, AGORAPHOBIC NOSEBLEED Fans of strippers, hard drugs, punk rock production and cock rock douchebaggery, rejoice: The one and only ANAL CUNT have returned with a new album, and this time around, they’re shooting to thrill –instead of just horrifically maim. They’re here to f*** your girlfriend, steal your drugs, piss in your whiskey, and above all, ROCK! (The late) Seth Putnam channels Sunset Strip scumbags like MOTLEY ARTIST: ANAL CUNT CRUE and TWISTED SISTER to bring you a rock’n’roll nightmare fueled TITLE: Fuckin’ A by their preferred cocktail of sex, violence, and unbridled disgust. From LABEL: PATAC ripping off theCRUE’s cover art to the massive hard rock riffs of “Hot Girls CAT#: PATAC-011 on the Road,” “Crankin’ My Band’s Demo on a Box at the Beach,” and “F*** FORMAT: CD YEAH!” and tender ballad “I Wish My Dealer Was Open,” Fuckin’ A is an GENRE: Metal instant scuzz rock classic. BOX LOT: 30 SRLP: $10.98 UPC: 628586220218 EXPORT: NO SALES TO THE UK Marketing Points: • 1ST PRESS LIMITED TO 1000 COPIES. Currently on its third pressing! • Final album before the passing of ANAL CUNT frontman Seth Putnam Tracklist: • Print ads in Maximumrocknroll, Decibel, Short Fast & Loud and Chips & Beer 1. -

Spring Season Brings All That Jazz

Tulane University Spring Season Brings All That Jazz April 25, 2008 1:00 AM Kathryn Hobgood [email protected] This spring brings a bustle of activity for jazz musicians at Tulane University. In addition to multiple performances at the famous New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, campus musicians students as well as more experienced jazzmen on the faculty have a whole lot going on. John Doheny, a professor of practice, plays sax while Jim Markway, a tutor in the Newcomb Department of Music, plays bass in the Professors of Pleasure jazz quintet. (Photo by Kathryn Hobgood) This week, the Tulane Jazz Orchestra will be busy with several appearances. On Tuesday (April 29), the orchestra will have its end-of-semester concert at 8 p.m. in Dixon Theatre. Smaller jazz combos will perform on Wednesday (April 30) beginning at 6 p.m. in Dixon Recital Hall. And on Friday (May 2), the orchestra will perform on the Gentilly Stage at the New Orleans Jazzfest at 11:35 a.m. Tulane students are the musicians in the Tulane Jazz Orchestra. The orchestra is directed by John Doheny, a professor of practice in the Newcomb Department of Music, who is extra busy this season. Doheny teaches jazz theory, history and applied private lessons, in addition to directing the student jazz ensembles. He also is a working musician. A project that came to fruition for Doheny recently was the Tulane faculty jazz quintet's first CD. Dubbing themselves the “Professors of Pleasure,” the quintet features Doheny on saxophone; John Dobry, a professor of practice, on guitar; Jim Markway on bass; and Kevin O'Day on drums. -

6 News Features 18 22

FALL 2019 | VOLUME 33 NO. 3 news 6(1)a GOES ALL THE WAY! . 6 by Melodie McCullough CANADA PLEDGES MILLIONS TO AID WOMEN GLOBALLY . 8 by Penney Kome WOMEN DELIVER ON EFFORTS TO END FGM . 9 by Lucas Aykroyd INDIA’S #METOO MOVEMENT TAKES HOLD . 11 by Deepa Kandaswamy ABORTION DOULAS REACH OUT . 12 6 by Elizabeth Whitten Photo: Nik K. Gehl features VIVEK SHRAYA . 14 Transforming Transphobia Vivek Shraya, who came out as trans in 2016, said that her Hindu community helped nurture her gender non- conformity in the 1980s. However, her journey has not been an easy one. Shraya received hate mail, including death threats in 2017, and responded by creating a comic book called Death Threat with visual artist Ness Lee. 18 by Megan Butcher LIBBY DAVIES . .. 18 From the Grassroots to the Commons Libby Davies, Canada’s first out-lesbian MP, was, for six terms, a passionate advocate for the underprivileged, including those she served as MP for Vancouver East, a constituency that includes Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Her new memoir, Outside In, is a fascinating telling of her time in office. by Cindy Filipenko ANDREA DWORKIN . 22 The Phoenix Rises A new collection of the works of Andrea Dworkin offers a timely re-examination of the radical feminist and the era of the 1980s “sex wars” over pornogra- phy and free expression. Johanna Fateman, co-editor of Last Days at Hot Slit: The Radical Feminism of Andrea Dworkin offers some surprising lessons about Dworkin’s works for feminists today. 22 by Susan G. Cole HERIZONS FALL 2019 1 From Grassroots to the Commons Former MP Libby Davies on Why Parliament Needs More Activists by CINDY FILIPENKO Libby Davies served ibby Davies’ new political memoir, Published in May to enthusiastic reviews, six consecutive terms Outside In, is striking in its humanity, Outside In has brought the former MP back to as MP for Vancouver East, and, prior to hope and honesty. -

SPRING 2016 Main Street News the Newsletter of the Old Algiers Main Street Corporation

SPRING 2016 Main Street News The Newsletter of the Old Algiers Main Street Corporation Tickets Available for Community Crawfish Boil You will definitely get your fill of crawfish – and more -- at the first annual Old Algiers Crawfish Boil on Saturday, May 7, 1 p.m.-5 p.m., at 922 Teche Street/corner of Newton Street. The event is presented by Old Algiers Main Street Corporation and the Pride of Algiers Masonic Temple Booster Club, both non-profit organizations. Advance tickets are now available from members of either organization for $25 for adults ($30 at the gate). The “all-you-can eat” price includes crawfish, potatoes, corn and sausage. Tickets for youths under 18 years- old are $15, and there is no charge for children under six years-old. A DJ will provide entertainment throughout the event. Bring your own chair for comfort! Crawfish box sponsors are still being sought. Current sponsors include Hamp’s Construction and Pro Paint. For sponsorship and ticket information, contact Joseph Evans, 504-812-0193 or Karri Maggio, 504-908-8476. In addition to Evans and Maggio, the joint committee includes Valerie Miller, Beryl Ragas, Delores Becnel and Alex Selico Dunn from OAMSC and Jason Hill, Kenneth Brown Sr., John Jackson, Sundiata Hall, Derron Walker and Jack Davis from the Pride of Algiers Boosters. OAMSC Elects 2016 Board OAMSC to Join with Harmony Karri Maggio has been elected president of Old Algiers Main Street Corporation for 2016. Other for Development Plan officers are Beryl Ragas, vice president; Valerie Harmony Neighborhood Development, which has been a successful Miller, secretary and Lourdes Moran, treasurer. -

February, ·1943 War Bonds - Our Standing

THE MILWAUKEE· MAGAZINE l'uhlbhc(l hy lhe CHICAGO, MILWAlIKEE, ST. PAUl: and PACIFIC RAILROAD COMPANY February, ·1943 War Bonds - Our Standing E HAVE almost reached the 90 percent mark set by the Government for participa Wtion in the payroll allotment plan for the purchase of War Savings Bonds. As of January 16 our figure was 89 percent, and by the time this magazine is off the press we may have passed 90 percent. It is mighty good to know that this large proportion of Milwaukee Road employes has answered the appeal of our Government to help the war effort in this way, and we hope those who have not yet signed up will do so in the near future so we can inform the Treasury Department that we are close to 100 percent. That this can be done is proved by the Madison division with 99.4 percent of its employes subscri~ing; the I. &S. M. Division with 99 percent; the Milwaukee Division with 97.7 percent; Tomah shops with 96.5 per cent, and other divisions, terminals and shops that have done better than 90 percent. In the Chicago and Seattle general offices the 100 percent mark has been reached by the departments of Purchases and Stores, Law, and Public Relations, as well as the offices of Secretary, Treasurer, and Trustee; the Accounting Department has subscribed 99.7 per cent; Traffic Department, 99.4 percent; and the Operating Department, 98.3 percent. We are still far short of the other goal set by the government -10 percent of the payroll for War Bonds. -

Order Form Full

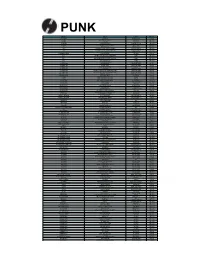

PUNK ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 100 DEMONS 100 DEMONS DEATHWISH INC RM90.00 4-SKINS A FISTFUL OF 4-SKINS RADIATION RM125.00 4-SKINS LOW LIFE RADIATION RM114.00 400 BLOWS SICKNESS & HEALTH ORIGINAL RECORD RM117.00 45 GRAVE SLEEP IN SAFETY (GREEN VINYL) REAL GONE RM142.00 999 DEATH IN SOHO PH RECORDS RM125.00 999 THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT (200 GR) DRASTIC PLASTIC RM121.00 999 THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT (GREEN) DRASTIC PLASTIC RM121.00 999 YOU US IT! COMBAT ROCK RM120.00 A WILHELM SCREAM PARTYCRASHER NO IDEA RM96.00 A.F.I. ANSWER THAT AND STAY FASHIONABLE NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. BLACK SAILS IN THE SUNSET NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. SHUT YOUR MOUTH AND OPEN YOUR EYES NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. VERY PROUD OF YA NITRO RM119.00 ABEST ASYLUM (WHITE VINYL) THIS CHARMING MAN RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE ARCHIVE TAPES UNREST RECORDS RM108.00 ACCUSED, THE BAKED TAPES UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE NASTY CUTS (1991-1993) UNREST RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE OH MARTHA! UNREST RECORDS RM93.00 ACCUSED, THE RETURN OF MARTHA SPLATTERHEAD (EARA UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE RETURN OF MARTHA SPLATTERHEAD (SUBC UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACHTUNGS, THE WELCOME TO HELL GOING UNDEGROUND RM96.00 ACID BABY JESUS ACID BABY JESUS SLOVENLY RM94.00 ACIDEZ BEER DRINKERS SURVIVORS UNREST RM98.00 ACIDEZ DON'T ASK FOR PERMISSION UNREST RM98.00 ADICTS, THE AND IT WAS SO! (WHITE VINYL) NUCLEAR BLAST RM127.00 ADICTS, THE TWENTY SEVEN DAILY RECORDS RM120.00 ADOLESCENTS ADOLESCENTS FRONTIER RM97.00 ADOLESCENTS BRATS IN BATTALIONS NICKEL & DIME RM96.00 ADOLESCENTS LA VENDETTA FRONTIER RM95.00 ADOLESCENTS -

Humanitas 2002 NEW.Indd

humanitasThe Bulletin of the Institute for the Humanities Volume One: Spring 2002 S I M O N F R A S E R U N I V E R S I T Y humanitas Staff Don Grayston, Trish Graham, Director Program Assistant Humanitas editors Jerry Zaslove Trish Graham Donald Grayston Layout and design Eryn Holbrook Program Information, Continuing Studies About the Institute Steering Committee The Institute for the Humanities at Simon Fraser Donald Grayston University, now almost twenty years in existence, Institute Director and Department of Humanities Faculty, initiates, supports and promotes programs devoted Simon Fraser University to the exploration and dissemination of knowledge Stephen Duguid about the traditional and modern approaches to the Department of Humanities Faculty and Chair, study of the humanities. Simon Fraser University The Institute sponsors a wide variety of community- Mary Ann Stouck based activities, along with its university-based Department of Humanities and English Faculty, academic programs. Simon Fraser University Ian Angus Institute for the Humanities Department of Humanities Faculty, Simon Fraser University Simon Fraser University 8888 University Drive Tom Nesbit Burnaby, B.C. V5A 1S6 Director, Centre for Integrated and Credit Studies, Fax: 604-291-5855 Continuing Studies, Simon Fraser University 2 Table of Contents 5 Director’s Letter Director, Donald Grayston 6 Humanitas: A Commentary Director Emeritus, Jerry Zaslove Issues of Peace: Violence and its Alternatives 9 Make Sense Not War: Lloyd Axworthy Receives Thakore Visiting Scholar -

America's Hardcore.Indd 278-279 5/20/10 9:28:57 PM Our First Show at an Amherst Youth Center

our first show at an Amherst youth center. Scott Helland’s brother Eric’s band Mace played; they became The Outpatients. Our first Boston show was with DYS, The Mighty COs and The AMERICA’S HARDCORE FU’s. It was very intense for us. We were so intimidated. Future generations will fuck up again THE OUTPATIENTS got started in 1982 by Deep Wound bassist Scott Helland At least we can try and change the one we’re in and his older brother Eric “Vis” Helland, guitarist/vocalist of Mace — a 1980-82 — Deep Wound, “Deep Wound” Metal group that played like Motörhead but dug Black Flag (a rare blend back then). The Outpatients opened for bands like EAST COAST Black Flag, Hüsker Dü and SSD. Flipside called ’em “one of the most brutalizing live bands In 1980, over-with small cities and run-down mill towns across the Northeast from the period.” 1983’s gnarly Basement Tape teemed with bored kids with nothing to do. Punk of any kind earned a cultural demo included credits that read: “Play loud in death sentence in the land of stiff upper-lipped Yanks. That cultural isolation math class.” became the impetus for a few notable local Hardcore scenes. CANCEROUS GROWTH started in 1982 in drummer Charlie Infection’s Burlington, WESTERN MASSACHUSETTS MA bedroom, and quickly spread across New had an active early-80s scene of England. They played on a few comps then 100 or so inspired kids. Western made 1985’s Late For The Grave LP in late 1984 Mass bands — Deep Wound, at Boston’s Radiobeat Studios (with producer The Outpatients, Pajama Slave Steve Barry). -

Great Beginnings: Old Streets, New Pride 2008 Project Progress Report

Great Beginnings: Old Streets, New Pride 2008 Project Progress Report and Evaluation Project Progress Report and Evaluation, January 2009 Table of Contents 1. The Great Beginnings Program - Background ................................................................3 2. Methods of Measurement .......................................................................................4 3. Overview of Program Activities to Date ......................................................................5 Downtown Eastside Awning Improvement ..................................................................5 Downtown Eastside Historic Neighbourhoods Map Guides................................................6 Blood Alley Community Greening ............................................................................7 29 West Hastings Street Facade ..............................................................................8 Pennsylvania Hotel Façade and Neon Light.................................................................9 Chinatown Parkade Neon Sign .............................................................................. 10 Princess Avenue Interpretive Walk Mural and Markers .................................................. 11 The Windows Project......................................................................................... 12 Anti-Graffiti Project - community murals................................................................. 13 Anti-Graffiti Project - BC Hydro pad mounted transformer (PMT) beautification pilot .......... -

Issue 3 April 2006

X Volume 6, Issue 3 April 2006 to suck. Or you don’t rock. We get that all the time. “Oh you guys were way better than I thought you were going to be”. Well, why ? Because we have breasts. I wanted to ask you about the name PANTYCHRIST. Where did that come from and what is the significance of the name ? Did it come in anyway from the band CONDO-CHRIST because there was a band from London called CONDO-CHRIST ? P: No. We didn’t even know that. D: CONDOM CHRIST ? No CONDO-CHRIST. P: This guy from another band had been watching us jam and we were tossing around names and we couldn’t come up with anything and he named us. We didn’t even know but there is another PANTY CHRIST. Some cross- dressing Japanese sampling guy who e-mailed us and said “Cool, use my name”. That’s okay. So that was cool. That is good. D: It’s because Izabelle looks really good in underwear. When we first started playing she PANTYCHRIST (FROM LEFT TO RIGHT): Amy with her back to us, Danyell on vocals, and Izabelle used to wear her underwear on stage. It was on guitar. Bob the Builder underwear. A couple of times in a row. You must have had those on for a PANTYCHRIST are a 4-piece punk band from while. No just joking (laughter). the steel capital of Canada. At the time of this What is the scene like in Hamilton ? From interview the band had released an 8-song our perspective it seems like a pretty thriving demo, a self-released ep, and were about to scene. -

Punk Record Labels and the Struggle for Autonomy 08 047 (01) FM.Qxd 2/4/08 3:31 PM Page Ii

08_047 (01) FM.qxd 2/4/08 3:31 PM Page i Punk Record Labels and the Struggle for Autonomy 08_047 (01) FM.qxd 2/4/08 3:31 PM Page ii Critical Media Studies Series Editor Andrew Calabrese, University of Colorado This series covers a broad range of critical research and theory about media in the modern world. It includes work about the changing structures of the media, focusing particularly on work about the political and economic forces and social relations which shape and are shaped by media institutions, struc- tural changes in policy formation and enforcement, technological transfor- mations in the means of communication, and the relationships of all these to public and private cultures worldwide. Historical research about the media and intellectual histories pertaining to media research and theory are partic- ularly welcome. Emphasizing the role of social and political theory for in- forming and shaping research about communications media, Critical Media Studies addresses the politics of media institutions at national, subnational, and transnational levels. The series is also interested in short, synthetic texts on key thinkers and concepts in critical media studies. Titles in the series Governing European Communications: From Unification to Coordination by Maria Michalis Knowledge Workers in the Information Society edited by Catherine McKercher and Vincent Mosco Punk Record Labels and the Struggle for Autonomy: The Emergence of DIY by Alan O’Connor 08_047 (01) FM.qxd 2/4/08 3:31 PM Page iii Punk Record Labels and the Struggle for Autonomy The Emergence of DIY Alan O’Connor LEXINGTON BOOKS A division of ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC.