A Case-Study from Central Naples1 Italo Pardo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rough Guide to Naples & the Amalfi Coast

HEK=> =K?:;I J>;HEK=>=K?:;je CVeaZh i]Z6bVaÒ8dVhi D7FB;IJ>;7C7B<?9E7IJ 7ZcZkZcid BdcYgV\dcZ 8{ejV HVc<^dg\^d 8VhZgiV HVciÉ6\ViV YZaHVcc^d YZ^<di^ HVciVBVg^V 8{ejVKiZgZ 8VhiZaKdaijgcd 8VhVaY^ Eg^cX^eZ 6g^Zcod / AV\dY^EVig^V BVg^\a^Vcd 6kZaa^cd 9WfeZ_Y^_de CdaV 8jbV CVeaZh AV\dY^;jhVgd Edoojda^ BiKZhjk^jh BZgXVidHVcHZkZg^cd EgX^YV :gXdaVcd Fecf[__ >hX]^V EdbeZ^ >hX]^V IdggZ6ccjco^ViV 8VhiZaaVbbVgZY^HiVW^V 7Vnd[CVeaZh GVkZaad HdggZcid Edh^iVcd HVaZgcd 6bVa[^ 8{eg^ <ja[d[HVaZgcd 6cVX{eg^ 8{eg^ CVeaZh I]Z8Vbe^;aZ\gZ^ Hdji]d[CVeaZh I]Z6bVa[^8dVhi I]Z^haVcYh LN Cdgi]d[CVeaZh FW[ijkc About this book Rough Guides are designed to be good to read and easy to use. The book is divided into the following sections, and you should be able to find whatever you need in one of them. The introductory colour section is designed to give you a feel for Naples and the Amalfi Coast, suggesting when to go and what not to miss, and includes a full list of contents. Then comes basics, for pre-departure information and other practicalities. The guide chapters cover the region in depth, each starting with a highlights panel, introduction and a map to help you plan your route. Contexts fills you in on history, books and film while individual colour sections introduce Neapolitan cuisine and performance. Language gives you an extensive menu reader and enough Italian to get by. 9 781843 537144 ISBN 978-1-84353-714-4 The book concludes with all the small print, including details of how to send in updates and corrections, and a comprehensive index. -

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY the Roman Inquisition and the Crypto

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY The Roman Inquisition and the Crypto-Jews of Spanish Naples, 1569-1582 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of History By Peter Akawie Mazur EVANSTON, ILLINOIS June 2008 2 ABSTRACT The Roman Inquisition and the Crypto-Jews of Spanish Naples, 1569-1582 Peter Akawie Mazur Between 1569 and 1582, the inquisitorial court of the Cardinal Archbishop of Naples undertook a series of trials against a powerful and wealthy group of Spanish immigrants in Naples for judaizing, the practice of Jewish rituals. The immense scale of this campaign and the many complications that resulted render it an exception in comparison to the rest of the judicial activity of the Roman Inquisition during this period. In Naples, judges employed some of the most violent and arbitrary procedures during the very years in which the Roman Inquisition was being remodeled into a more precise judicial system and exchanging the heavy handed methods used to eradicate Protestantism from Italy for more subtle techniques of control. The history of the Neapolitan campaign sheds new light on the history of the Roman Inquisition during the period of its greatest influence over Italian life. Though the tribunal took a place among the premier judicial institutions operating in sixteenth century Europe for its ability to dispense disinterested and objective justice, the chaotic Neapolitan campaign shows that not even a tribunal bearing all of the hallmarks of a modern judicial system-- a professionalized corps of officials, a standardized code of practice, a centralized structure of command, and attention to the rights of defendants-- could remain immune to the strong privatizing tendencies that undermined its ideals. -

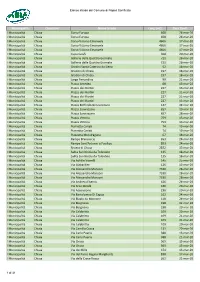

Municipalità Quartiere Nome Strada Lung.(Mt) Data Sanif

Elenco strade del Comune di Napoli Sanificate Municipalità Quartiere Nome Strada Lung.(mt) Data Sanif. I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Europa 608 24-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Europa 608 24-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Cupa Caiafa 368 20-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Galleria delle Quattro Giornate 721 28-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Galleria delle Quattro Giornate 721 28-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradini Santa Caterina da Siena 52 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradoni di Chiaia 197 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradoni di Chiaia 197 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Largo Ferrandina 99 21-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Amedeo 68 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 21-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 21-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Roffredo Beneventano 147 24-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Sannazzaro 657 20-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Sannazzaro 657 28-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Vittoria 759 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Vittoria 759 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Cariati 74 19-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Cariati 74 19-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Mondragone 67 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Rampe Brancaccio 653 24-mar-20 I Municipalità -

The Impact of Transport Management on the Local Activities System: the Role of Limited Traffic Zones

Urban Transport XX 669 The impact of transport management on the local activities system: the role of limited traffic zones L. Biggiero Department of Civil, Building and Environmental Engineering, University Federico II of Naples, Italy Abstract The impacts of transportation in planning land use and activities are not always intended and can have unforeseen or unintended consequences such as congestion or evident impacts on the local economy where the interventions are conceived. This is the case for Limited Traffic Zones (LTZs), i.e. areas where cars are not allowed in them. In this paper, the impact of these measures on the local economy is analysed, considering as a case study the town of Napoli in the south of Italy, where two Limited Traffic Zones, in two different boroughs and years, named Vomero and Chiaia, have been introduced. Moreover, the impacts due to changes involving one of the LTZ’s areas are also observed and analysed through a before-after survey. The direct impact on traffic congestion has not been taken into account. More than 30% of all activities have been interviewed in the two restricted areas and some key points have been assessed for the successful or unsuccessful of car restriction measure. Retailers were also asked about their decrease in turnover in order to evaluate the effects of the LTZ’s area after taking into account the actual economic crisis. The survey showed how much the retailers require: efficient public transport; parking places as close as possible; residential and activity density and typology. Those are the main reasons for the success of the Vomero LTZ zone and of the failure of the Chaia restricted zone. -

Local Activities to Raise Awareness And

LOCAL ACTIVITIES TO RAISE AWARENESS AND PREPAREDNESS IN NEAPOLITAN AREA Edoardo Cosenza, Councillor for Civil Protection of Campania Region, Italy (better: professor of Structural Enngineering, University of Naples, Italy) Mineral and thermal water Port of Ischia (last eruption 1302) Campi Flegrei, Monte Nuovo, last eruption 1538 Mont Vesuvius, last eruption : march 23, 1944 US soldier and B25 air plan, Terzigno military base Municpalities and twin Regions 2 4 3 1 Evento del (Event of) 24/10/1910 Vittime (Fatalities) 229 Cetara 120, Maiori 50, Vietri sul Mare 50, Casamicciola Terme 9 Evento del (Event of) 25-28/03/1924 Vittime (Fatalities) 201 Amalfi 165, Praiano 36 Evento del (Event of) 25/10/1954 Vittime (Fatalities) 310 Salerno 109, Virtri sul Mare 100, Maiori 34, Cava de’ Tirreni 42, Tramonti 25, Evento del (Event of) 05/05/1998 Vittime (Fatalities) 200 Sarno area 184, Quindici 16 Analisi del dissesto da frana in campania. L.Monti, G.D’Elia e R.M.Toccaceli Atrani, September 2010 Cnr = National Council of Research From 1900: 51% of fatalities in Italy in the month of October !!! Cnr = National Council of Research From 1900: 25% of fatalities in Italy in Campania Region !!! Ipotesi nuova area rossa 2013 Municipi di Napoli Municipi di Napoli Inviluppo dei 1 - Chiaia,Posillipo, Inviluppo dei 1 - Chiaia,Posillipo, depositi degli ultimi S.Ferdinando depositi degli ultimi S.Ferdinando2 - Mercato, Pendino, 55 KaKa 2Avvocata, - Mercato, Montecalvario, Pendino, Avvocata,Porto, San Giuseppe.Montecalvario, Porto,3 - San San Giuseppe.Carlo all’Arena, 3Stella - San Carlo all’Arena, Stella4 - San Lorenzo, Vicaria, 4Poggioreale, - San Lorenzo, Z. -

The Thesis Plan

Guglielmi’s Lo spirito di contradizione: The fortunes of a mid-eighteenth-century opera VOLUME ONE STUDY AND COMMENTARY Nancy Calo Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Music (Musicology) University of Melbourne 2013. ii THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE Faculty of the VCA and MCM TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN This is to certify that the thesis presented by me for the degree of Master of Music (Musicology) comprises only my original work except where due acknowledgement is made in the text to all other material used. Signature: ______________________________________ Name in Full: ______________________________________ Date: ______________________________________ iii ABSTRACT Pietro Alessandro Guglielmi’s opera buffa or bernesca, titled Lo spirito di contradizione, premièred in Venice in 1766. It was based on another work that had successfully premièred in 1763 as a Neapolitan opera: Lo sposo di tre, e marito di nessuna. The libretto for Lo sposo di tre, e marito di nessuna was written by Antonio Palomba, and concerns a man who attempts to marry three women and escape with their dowries. In setting this opera, Guglielmi collaborated with Neapolitan composer Pasquale Anfossi, with the former contributing the Opening Ensemble, the three finali and the Baroness’s aria in the third act. After moving to Venice in the mid 1760s, Guglielmi requested Gaetano Martinelli to re- fashion the libretto, keeping the story essentially the same for his new opera Lo spirito di contradizione. Guglielmi wrote all the music for his new production, retaining some of his former ideas. I argue that Pietro Alessandro Guglielmi was a prominent composer and significant eighteenth-century industry figure whose output should be re-incorporated into the repertory of modern performance. -

A System of Location Models for the Evaluation of Long Term Impacts of Transport Policies

A SYSTEM OF LOCATION MODELS FOR THE EVALUATION OF LONG TERM IMPACTS OF TRANSPORT POLICIES GENNARO NICOLA BIFULCO Université degli Studi di Roma"Tor Vergata" Dipartimento d'Ingegneria Civile Via di Tor Vergata s.n.c., 00133 ROMA, ITALY Abstract In this article an analytical model able to deal with the complex interactions among the activities of an urban system is presented. The model is based on a consistent and rigorous analytical framework, where the urban pattern results from the location choices of various decision- makers. The model can be stated in a disaggregate form where choices are simulated within a behavioural framework based on the random utility theory. Aggregation issues can also be consistently treated. An operative specification of the model is also presented, as well as its application to the urban area of Naples. VOLUME 3 93 8TH WCTR PROCEEDINGS INTRODUCTION The main aim of this paper is to present an analytical model able to deal with the complex set of activities' interactions of an urban system. Urban systems are complex, since they are described by a large number of variables, are characterised by non-linear relationships among variables, dynamic dependencies and a system evolution that is dependent on behavioural factors. Three main sub-systems can be identified within an urban system: transportation, land market and urban activities. Within urban activities, in turn, three further subsystems can be recognised: housing, employment and workplace. Housing depends on where households locate their residences, employment depends on where firms locate their activities and workplace depends on where people choose to locate their job (choosing among the available employment). -

3. Libreria/Cartolibreria

1. Libreria/cartolibreria “G. GUERRETTA” CORSO PONTICELLI 10/12 - CAP 80147 Municipalità 6 - Ponticelli, Barra, S. Giovanni a Teduccio Recapito telefonico fisso e/o cellulare: 081 5967809 3891536808 Indirizzo di posta elettronica: [email protected] LIBRI SCOLASTICI E CANCELLERIA UFFICIO 2. Libreria/cartolibreria “MARIO BRUNETTI” CORSO VITTORIO EMANUELE 286 80122 Municipalità 1- Chiaia, Posillipo, S. Ferdinando Recapito telefonico fisso e/o cellulare: 081405981 Indirizzo di posta elettronica: [email protected] TESTI UNIVERSITARI - TESTI PREPARAZIONI CONCORSI- NARRATIVA STRANIERA 3. Libreria/cartolibreria “Gomma e Matita di Pietro Autiero” Via Silio Italico 56 C – CAP 80124 Municipalità 10 - Bagnoli, Fuorigrotta Recapito telefonico fisso e/o cellulare: 3391687104 Indirizzo di posta elettronica: [email protected] Libri vari, scolastici e per ragazzi. Articoli per ufficio e scuola. Servizi telematici 4. Libreria/cartolibreria “Il Mattoncino” Via Posillipo 305 CAP 80123 Municipalità 1- Chiaia, Posillipo, S. Ferdinando Recapito telefonico fisso e/o cellulare: 3296265074 Indirizzo di posta elettronica: [email protected] Libreria Indipendente per bambine e bambini, specializzata in libri per l'infanzia, albi illustrati, letteratura per ragazzi. È presente anche una selezione di libri per adulti. 5. Libreria/cartolibreria “Libreria Dante & Descartes” Piazza del Gesù Nuovo 14 CAP 80134 Municipalità 2 - Avvocata, Montecalvario, Mercato, Pendino, Porto, S. Giuseppe Recapito telefonico fisso e/o cellulare: 0814202413 Indirizzo di posta elettronica: [email protected] Due librerie animate da una passione: vendere libri. Antichi, rari, esauriti, nuovi, universitari? In questo tempo di consumismo e di menzogne, di supermercati impersonali e virtuali anche per i libri, le librerie vanno perdendo la propria identità. Dal fondo della città, noi continuiamo la tradizione, inattuale ma opportuna, degli antichi librai. -

Leggere La Parola Di

SEGNIgiornale di attualitàdei sociale, culturaleTEMPI e religiosa n. 1 - gennaio 2020 | anno XXV | Registrazione del Tribunale di Napoli n° 5185 del 26 febbraio 2001 www.diocesipozzuoli.org | www.segnideitempi.it Il 26 gennaio ci sarà la giornata istituita dal Papa per rafforzare i legami con gli ebrei e pregare per l’unità dei cristiani LEGGERE LA PAROLA DI DIO Non c'è evangelizzazione se non è radicata in una conoscenza più approfondita della Bibbia I mio rapporto con la Bibbia risale a tanto Itempo fa, alla mia infanzia, a un premio ricevuto da mio padre come terzo classifica- to al concorso parrocchiale di presepi. Ave- vo sperato con tutte le mie forze che quello fosse il piazzamento. Non ambivo a vince- re, non ricordo quale fosse il primo premio, ma io volevo quella Bibbia... Avevo 9 anni, e leggevo tanti libri: quello, però, non an- cora, e perciò mi incuriosiva. Quando lo ebbi tra le mani, non aspettai nemmeno un giorno per iniziare a leggerlo. Lo lessi tutto (beh, saltai alcune parti, quelle più "noio- se", come le genealogie o i salmi...), dalla prima pagina all'ultima, da "In principio Dio creò il cielo e la terra" della Genesi al "Vieni, Signore Gesù" dell'Apocalisse. Ne fui travolto. Gli altri libri raccontavano una storia, e questo mi affascinava; ma capii ben presto che in quel libro (non sapevo ancora che in realtà era un'intera biblioteca di ben 73 libri!) erano raccontate centinaia e centi- naia di storie, tutte estremamente coinvol- genti. E che non c'era un solo protagonista, ma si passava da Adamo ai due testimoni dell'Apocalisse attraversando intere genera- zioni, secoli e secoli di storie di uomini e donne. -

Punti Vendita

RAGIONE SOCIALE CATEGORIA INDIRIZZO CITTA QUARTIERE CHIUSO DAL AL ALFANO GIOVANNI EDICOLA INT. STAZ. MONTESANTO NAPOLI MONTECALVARIO 10‐ago 24‐ago AMABILE L. EDICOLA S. TERESA A CHIAIA NAPOLI CHIAIA 8‐ago 30‐ago ANNUNZIATA NATALE BAR ROMA CORSO GARIBALDI 378 NAPOLI PENDINO SEMPRE APERTO APREA RITA riv. n° 52 Via S.Maria in Portico 38 NAPOLI CHIAIA SEMPRE APERTO ARCOPINTO CARMELA EDICOLA TRAV. DOMENICO DI GRAVINA NAPOLI AVVOVATA SEMPRE APERTO Artuso Pasquale riv. n° 462 C.so S.Giovanni a Teduccio 1032 NAPOLI SAN GIOVANNI A TEDUCCIO Aperto fino 23/8 al 23/8 BILLANOVA IMMACOLATA riv. n°88 Via Mazzocchi 16 NAPOLI SAN CARLO ALL'ARENA SEMPRE APERTO BOLLINO IDA EDICOLA P.ZZA SAN PASQUALE NAPOLI CHIAIA 10‐ago 23‐ago BRANCACCIO MARIA CORSO V. EMANUELE NAPOLI MONTECALVARIO 4‐ago 30‐ago BRESCIA AGOSTINO riv. n° 367 Via del Macello 42 NAPOLI POGGIOREALE SEMPRE APERTO CALEMME FRANCESCO ALIM. V ALTAIR 15/BIS NAPOLI SECONDIGLIANO 1‐ago 30‐ago Califano Concetta riv. 77 Via Rossetti 34 NAPOLI AVVOVATA SEMPRE APERTO CAMPOLONGO EDUARDO EDICOLA P.ZZA MIRAGLIA NAPOLI SAN LORENZO SEMPRE APERTO COLINI GIULIA EDICOLA PIAZZA SANNAZZARO NAPOLI 10‐ago 25‐ago BAR AZZURRO Bar Via Stadera 211 NAPOLI VICARIA SEMPRE APERTO CAPRIO GIOSUE' EDICOLA VIA MORGHEN (IT.STAZ.FUN.) NAPOLI VOMERO 7‐ago 30‐ago CAPUANO GIOVANNI EDICOLA PIAZZA SALV. DI GIACOMO NAPOLI SEMPRE APERTO CARAMIELLO CLAUDIO TABACCHI VIA NAZIONALE, 28 NAPOLI VICARIA 14‐ago 29‐ago GIANCAR DI CARUSO GIOV. DISCHI PIAZZA GARIBALDI, 44 NAPOLI PENDINO SEMPRE APERTO CASSINI LUIGI EDICOLA VIA REGGIA DI PORTICI 55 NAPOLI ZONA INDUSTRIALE 9‐ago 24‐ago CAVALIERE MAX riv. -

Elenco Strade Sanificate Aggiornate Al 31 Marzo

ELENCO STRADE SANIFICATE AGGIORNATE AL 31 MARZO Municipalità Quartiere Nome Strada Lunghezza Data Bonifica I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Europa 608 24/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Cupa Caiafa 368 20/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Galleria delle Quattro Giornate 721 28/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradini del Petraio 232 27/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradini Santa Caterina da Siena 52 18/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradoni di Chiaia 197 18/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Largo Ferrandina 99 21/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Amedeo 68 13/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 13/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 21/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Roffredo Beneventano 147 24/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Sannazzaro 657 20/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Sannazzaro 657 28/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Vittoria 759 13/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Cariati 74 19/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Mondragone 67 18/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Rampe Brancaccio 653 24/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Rampe Sant'Antonio a Posillipo 893 24/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Riviera di Chiaia 2872 13/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Salita San Nicola da Tolentino 135 18/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Via Achille Vianelli 145 25/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Via Alabardieri 126 13/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Via Alessandro Manzoni 7330 28/03/2020 I Municipalità Chiaia Via Andrea d'Isernia 426 24/03/2020 I Municipalità -

Carabinieri 112 Polizia 113 Vigili Del Fuoco 115 Pronto

CARABINIERI 112 POLIZIA 113 VIGILI DEL FUOCO 115 PRONTO SOCCORSO 118 SOCCORSO STRADALE 803.116 GUARDIA DI FINANZA 117 VIGILI URBANI 081-7513177 AUTO RUBATE 081-7941435 POLIZIA STRADALE 081-5954111 081-2208311 ANTIRACKET CARABINIERI 081-5484519 081-5484515 ANTIRACKET POLIZIA 081-7941544 GUARDIA COSTIERA 1530 CENTRO ANTIVELENI 081-545333 081-5451889 C.R.I. 800358358 C. di S. Leonardo 081-5469127 081-7702428 ASL 1. 081-7528.282 081-7520.696 081-7520850 Neapolis Ambulance Service 081-7406475 Service Assistance 081-5854620 Ambrosiana 081-5453565 081-5454656 Croce Bianca 081-5454656 Croce S. Raffaele 081-5872490 C. Azzurra 081-5453565 081-5463884 C. Verde di Napoli 081-5442078 081-5447603 F.lli Bourelly Serv. Ambulanza 081-5591600 Eliambulanze (gratuita diurna) 800.081118 Elicottero Aereo 081-5844319 081-5844355 Servizio Eli notturno 081-7122962 Guardia medica. Il servizio funziona:feriali ore 20-8; sabato e prefestivi dalle 10 fino alle 8 della giornata di nuovo feriale. S. Ferdinando Chiaia Posillipo 081-7613466 081-2547215 Fuorigrotta Bagnoli 081-2390161 081-7686425 Soccavo Pianura 081-7672183 081-2548370 Vomero Arenella 081-5780760 081-2549764 Chiaiano Piscinola Marianella Scampia 081-7021116 081-2546501 Stella S. Carlo Arena 081-7517510 081-2549240 Miano Secondigliano S. Pietro a Patierno 081-7372803 081-2546627 Montecalvario Avvocata S. Giuseppe Porto Mercato Pendino 081-2542424 081-5494338 S. Giovanni Barra Ponticelli 081-5969818 S. Lorenzo Vicaria Poggioreale 081-202343 081-2549185 Pediatria Il servizio funziona dalle 8,30 alle 14,30. S. Ferdinando Chiaia 081-2547076 Fuorigrotta 081-7646879 Soccavo Pianura 081-2548348 Chiaiano 081.5854235 Piscinola Marianella Scampia 081-5851899 081-7065056 Miano 081-2352532 Secondigliano S.