Linguistic Constraints on Intrasentential Code-Switching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government and Binding Theory.1 I Shall Not Dwell on This Label Here; Its Significance Will Become Clear in Later Chapters of This Book

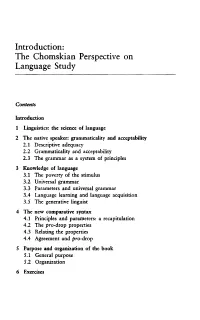

Introduction: The Chomskian Perspective on Language Study Contents Introduction 1 Linguistics: the science of language 2 The native speaker: grammaticality and acceptability 2.1 Descriptive adequacy 2.2 Grammaticality and acceptability 2.3 The grammar as a system of principles 3 Knowledge of language 3.1 The poverty of the stimulus 3.2 Universal grammar 3.3 Parameters and universal grammar 3.4 Language learning and language acquisition 3.5 The generative linguist 4 The new comparative syntax 4.1 Principles and parameters: a recapitulation 4.2 The pro-drop properties 4.3 Relating the properties 4.4 Agreement and pro-drop 5 Purpose and organization of the book 5.1 General purpose 5.2 Organization 6 Exercises Introduction The aim of this book is to offer an introduction to the version of generative syntax usually referred to as Government and Binding Theory.1 I shall not dwell on this label here; its significance will become clear in later chapters of this book. Government-Binding Theory is a natural development of earlier versions of generative grammar, initiated by Noam Chomsky some thirty years ago. The purpose of this introductory chapter is not to provide a historical survey of the Chomskian tradition. A full discussion of the history of the generative enterprise would in itself be the basis for a book.2 What I shall do here is offer a short and informal sketch of the essential motivation for the line of enquiry to be pursued. Throughout the book the initial points will become more concrete and more precise. By means of footnotes I shall also direct the reader to further reading related to the matter at hand. -

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish Silvia Perpiñán and Silvina Montrul University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction Ditransitive verbs can take a direct object and an indirect object. In English and many other languages, the order of these objects can be altered, giving as a result the Dative Construction on the one hand (I sent a package to my parents) and the Double Object Construction, (I sent my parents a package, hereafter DOC), on the other. However, not all ditransitive verbs can participate in this alternation. The study of the English dative alternation has been a recurrent topic in the language acquisition literature. This argument-structure alternation is widely recognized as an exemplar of the poverty of stimulus problem: from a limited set of data in the input, the language acquirer must somehow determine which verbs allow the alternating syntactic forms and which ones do not: you can give money to someone and donate money to someone; you can also give someone money but you definitely cannot *donate someone money. Since Spanish, apparently, does not allow DOC (give someone money), L2 learners of Spanish whose mother tongue is English have to become aware of this restriction in Spanish, without negative evidence. However, it has been noticed by Demonte (1995) and Cuervo (2001) that Spanish has a DOC, which is not identical, but which shares syntactic and, crucially, interpretive restrictions with the English counterpart. Moreover, within the Spanish Dative Construction, the order of the objects can also be inverted without superficial morpho-syntactic differences, (Pablo mandó una carta a la niña ‘Pablo sent a letter to the girl’ vs. -

3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement

e-Content Submission to INFLIBNET Subject name: Linguistics Paper name: Grammatical Categories Paper Coordinator name Ayesha Kidwai and contact: Module name A Framework for Grammatical Features -II Content Writer (CW) Ayesha Kidwai Name Email id [email protected] Phone 9968655009 E-Text Self Learn Self Assessment Learn More Story Board Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Features as Values 3. Contextual Features 3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement 4. A formal description of features and their values 5. Conclusion References 1 1. Introduction In this unit, we adopt (and adapt) the typology of features developed by Kibort (2008) (but not necessarily all her analyses of individual features) as the descriptive device we shall use to describe grammatical categories in terms of features. Sections 2 and 3 are devoted to this exercise, while Section 4 specifies the annotation schema we shall employ to denote features and values. 2. Features and Values Intuitively, a feature is expressed by a set of values, and is really known only through them. For example, a statement that a language has the feature [number] can be evaluated to be true only if the language can be shown to express some of the values of that feature: SINGULAR, PLURAL, DUAL, PAUCAL, etc. In other words, recalling our definitions of distribution in Unit 2, a feature creates a set out of values that are in contrastive distribution, by employing a single parameter (meaning or grammatical function) that unifies these values. The name of the feature is the property that is used to construct the set. Let us therefore employ (1) as our first working definition of a feature: (1) A feature names the property that unifies a set of values in contrastive distribution. -

Error Linguistics and the Teaching and Learning of Written English in Nigerian Universities As a Second Language Environment

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 9 Issue 6 Ser. I || June 2020 || PP 61-68 Error Linguistics and the Teaching and Learning of Written English in Nigerian Universities as a Second Language Environment MARTIN C. OGAYI Department of English and Literary Studies Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki. Abstract: Alarming decline of the written English language proficiency of graduates of Nigerian universities has been observed for a long period of time. This has engendered a startling and besetting situation in which most graduates of Nigerian universities cannot meet the English language demands of their employers since they cannot write simple letters, memoranda and reports in their places of work. Pedagogy has sought different methods or strategies to remedy the trend. Applied linguistics models have been developed towards the improvement of second or foreign language learning through the use of diagnostic tools such as error analysis. This paper focuses on the usefulness and strategies of error analysis as diagnostic tool and strategy for second language teaching exposes the current state of affairs in English as a Second Language learning in Nigerian sociolinguistic environment highlights the language-learning theories associated with error analysis, and, highlights the factors that hinder effective error analysis of written ESL production in Nigerian universities. The paper also discusses the role of positive corrective feedback as a beneficial error treatment that facilitates second language learning. Practical measures for achieving more efficient and more productive English as a Second Language teaching and learning in Nigerian universities have also been proffered in the paper. -

The Study of Errors and Feedback in Second Language Acquisition

IIUC STUDIES ISSN 1813-7733 Vol.- 8, December 2011 (p 131-140) The Study of Errors and Feedback in Second Language Acquisition (SLA) Research: Strategies used by the ELT practitioners in Bangladesh to address the errors their students make in learning English Md. Maksud Ali* Abstract: The study of errors and feedback is one of the major issues in Second Language Acquisition (SLA) research. The research in this area is so important because it gives the English language teaching (ELT) practitioners an opportunity to have an insight in understanding the nature of learners’ errors and in giving feedback to learners. Following quantitative method, this paper carries out an empirical cross-sectional survey research on errors and feedback in SLA in the context of Bangladesh in order to generalize the way in which the Bangladeshi ELT practitioners view their students’ errors and the ways they correct the errors. Key Words: Second Language (L2) Learners’ Errors, Mother Tongue (L1) Interference, Interlanguage, Contrastive Analysis (CA), Error Analysis (EA), Personal Competence, Fossilization, Feedback, Learner Autonomy 1 Introduction The study of errors made by the Second Language Learners (SLL) has been one of the major concerns in Second Language Acquisition (SLA) research. Earlier, it was generally considered that Second language (L2) Learners’ errors were the result of mother tongue (L1) interference. However, later there was a reaction against the view and some researchers came up with a new orthodoxy that ‘vast majority of errors’ were not due to L1 interference but rather they were because of their ‘unique linguistic * Lecturer, Department of English Language & Literature, IIUC. -

ECU International Student Writing Colloquium

INTERNATIONAL STUDENT WRITING COLLOQUIUM Working with International Student Writers: Perspectives from the Field of Second Language Writing February 10-11, 2021 12:00pm – 2:00pm ~All Sessions Delivered via Zoom~ Working with International Student Writers: Perspectives from the Field of Second Language Writing Program Description In this informal, virtual colloquium, world-renowned experts in the field of second language writing share their perspectives and tips on working with international student writers. While sessions target faculty who work with international student writers, faculty from throughout the UNC System are encouraged and welcome to attend. Program organized by Dr. Mark Johnson, Associate Professor of TESOL and Applied Linguistics, East Carolina University®. Program sponsored by the ECU Office of Global Affairs and the ECU Graduate School. Register now! Working with International Student Writers: Perspectives from the Field of Second Language Writing Program Schedule Time Speaker 12:00 pm – 12:45 pm Dr. Charlene Polio 12:45 pm – 1:30 pm Dr. Dana Ferris February 10, 2021 10, February 1:30 pm – 2:00 pm Question and Answer Session Time Speaker 2021 12:00 pm – 12:45 pm Dr. Christine Feak 12:45 pm – 1:30 pm Dr. Paul Kei Matsuda February 11, 1:30 pm – 2:00 pm Question and Answer Session Working with International Student Writers: Perspectives from the Field of Second Language Writing Wednesday, February 10, 12:00 – 12:45pm Speaker: Dr. Charlene Polio Title: Promoting Language and Genre Awareness across Contexts: Being All Things to All People Abstract: A genre approach to teaching writing may focus on a specific genre within a specific field, but we rarely have the luxury of teaching homogeneous groups of students, who do not have diverse goals and needs, particularly at lower proficiency levels. -

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory Robert J. Kuhns Artificial Intelligence Center Arthur D. Little, Inc. Cambridge, MA 02140 USA Abstrae_~t For the purposes (and space limitations) of A parser which is founded on Chomskyts this paper we only briefly describe the theories Government-Binding Theory and implemented in of X-bar, Theta, Control, and Binding. We also PROLOG is described. By focussing on systems of will present three principles, viz., Theta- constraints as proposed by this theory, the Criterion, Projection Principle, and Binding system is capable of parsing without an Conditions. elaborate rule set and subcategorization features on lexical items. In addition to the 2.1 X-Bar Theory parse, theta, binding, and control relations are determined simultaneously. X-bar theory is one part of GB-theory which captures eross-categorial relations and 1. Introduction specifies the constraints on underlying structures. The two general schemata of X-bar A number of recent research efforts have theory are: explicitly grounded parser design on linguistic theory (e.g., Bayer et al. (1985), Berwick and Weinberg (1984), Marcus (1980), Reyle and Frey (1)a. X~Specifier (1983), and Wehrli (1983)). Although many of these parsers are based on generative grammar, b. X-------~X Complement and transformational grammar in particular, with few exceptions (Wehrli (1983)) the modular The types of categories that may precede or approach as suggested by this theory has been follow a head are similar and Specifier and lagging (Barton (1984)). Moreover, Chomsky Complement represent this commonality of the (1986) has recently suggested that rule-based pre-head and post-head categories, respectively. -

Who Is a Jew?

Who is a Jew? Over the course of many millen- We all know that the identity of Jews at some of our very nia, the question of ‘Who is a Jew?’ worst moments in our collective history were evaluations made has been asked in many histori- by non-Jews filled with hatred who persecuted, punished and cal contexts across many geogra- murdered Jews for their ‘otherness.’ Whether murdered by the phies around the globe. While this Babylonians or Romans in Jerusalem during the destructions is a very old question asked many of the temples in 576 BCE and 70 CE, burned at the stake in times across centuries, today’s York, England in the 13th century, murdered in Mainz during world culture of the 21st century the crusades, tortured after being accused of causing the Black and some most troubling recent Plague in medieval Europe, killed during the Inquistion in Spain current events specifically in Israel in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, murdered in pograms presents a timely moment for me to throughout Eastern Europe and Russia in the 17th through 19th re-engage this question in my col- centuries, and slaughtered by the Nazis in a magnitude of more umn this month. than 6 million human beings in the 20th century, in all these cas- I recently shared with the congregation from the pulpit a es, these were horrors perpetrated upon us by non-Jews. statement from the Israeli Defense Forces chief rabbi. I pres- I remember a Holocaust film made over a decade ago about a ent it here again for our readers. -

Error Correction in the Second Language Classroom

VOLUME 11 ISSUE 2 FALL 2007 FeatURED THEME: Error correction in the second ERROR CORRECTION language classroom by Shawn Loewen The topic of error correction in the second language (L2) classroom tends to spark controversy among both language teachers and L2 acquisition researchers. Teachers may have very strong views about error correction, based on their own previous L2 learning experiences, or they may be more ambivalent, particularly if they have been following the debate among L2 researchers on the topic. Depending on which journal articles a teacher reads, he or she will find error correction described on a continuum ranging from ineffective and possibly harmful (e.g., Truscott, 1999) to beneficial (e.g., Russell & Spada, 2006) and possibly even essential for some grammatical structures (White, 1991). Furthermore, teachers may be confronted with students’ opinions about error correction since students are on the receiving end and often have their own views of if and how it should happen in the classroom. Given these widely varying views, what is a teacher to do? This article will address this question by exploring some of the current thinking about error correction in the field of L2 acquisition research. Before going further, it is important to clarify the context in which error correction will be considered. Second language instruction can be conceptualized as falling into two broad categories: meaning-focused instruction and form-focused instruction (Long, 1996; Ellis, 2001). Meaning-focused instruction is characterized by communicative language teaching and involves no direct, explicit attention to language form. The L2 is seen as a vehicle for learners to express their ideas. -

Syntax-Semantics Interface

: Syntax-Semantics Interface http://cognet.mit.edu/library/erefs/mitecs/chierchia.html Subscriber : California Digital Library » LOG IN Home Library What's New Departments For Librarians space GO REGISTER Advanced Search The CogNet Library : References Collection : Table of Contents : Syntax-Semantics Interface «« Previous Next »» A commonplace observation about language is that it consists of the systematic association of sound patterns with meaning. SYNTAX studies the structure of well-formed phrases (spelled out as sound sequences); SEMANTICS deals with the way syntactic structures are interpreted. However, how to exactly slice the pie between these two disciplines and how to map one into the other is the subject of controversy. In fact, understanding how syntax and semantics interact (i.e., their interface) constitutes one of the most interesting and central questions in linguistics. Traditionally, phenomena like word order, case marking, agreement, and the like are viewed as part of syntax, whereas things like the meaningfulness of a well-formed string are seen as part of semantics. Thus, for example, "I loves Lee" is ungrammatical because of lack of agreement between the subject and the verb, a phenomenon that pertains to syntax, whereas Chomky's famous "colorless green ideas sleep furiously" is held to be syntactically well-formed but semantically deviant. In fact, there are two aspects of the picture just sketched that one ought to keep apart. The first pertains to data, the second to theoretical explanation. We may be able on pretheoretical grounds to classify some linguistic data (i.e., some native speakers' intuitions) as "syntactic" and others as "semantic." But we cannot determine a priori whether a certain phenomenon is best explained in syntactic or semantics terms. -

Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto De Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic

Introduction: Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic To cite this version: Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic. Introduction: Complex Adpo- sitions and Complex Nominal Relators. Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Dejan Stosic, Elena Smirnova. Complex Adpositions in European Languages : A Micro-Typological Approach to Com- plex Nominal Relators, 65, De Gruyter Mouton, pp.1-30, 2020, Empirical Approaches to Language Typology, 978-3-11-068664-7. 10.1515/9783110686647-001. halshs-03087872 HAL Id: halshs-03087872 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03087872 Submitted on 24 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Public Domain Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Elena Smirnova & Dejan Stosic Introduction: Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard CNRS, ENS & Paris Sorbonne Nouvelle; PSL Lattice laboratory, Ecole Normale Supérieure, 1 rue Maurice Arnoux, 92120 Montrouge, France [email protected] -

Multilingualism in the United States: a Less Well-Known Source of Vitality in American Culture As an Issue of Social Justice and of Historical Memory

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE NANZAN REVIEW OF AMERICAN STUDIES Volume 31 (2009): 59-75 Proceedings of the NASSS 2009 Literature and Culture Multilingualism in the United States: A Less Well-Known Source of Vitality in American Culture as an Issue of Social Justice and of Historical Memory Werner SOLLORS HARVARD UNIVERSITY [The talk takes its point of departure from current signs of multilingualism in American Census 2000 and American culture, examines some “language rights” issues, and ends with an anthology that has collected cultural expression in America from the 17th century to today in languages other than English. I am grateful to Kelsey LeBuffe for her research assistance and to Professors Jun Furuya, Konomi Ara, Eric Muller, and Keiko Sakai for their comments.] I. The world now has more than six and a half billion inhabitants (on June 17, 2009, the estimate was exactly 6,787,163,241) who live in 193 countries and speak 6,912 languages (http://www.un.org/esa/population/unpop.htm, http://www.ethnologue.com/ethno_docs/distribution.asp?by=area). One could indulge in the fantasy that creating more nation states with only one single shared language would make for more harmony (“we have room but for one language,” Theodore Roosevelt famously said)―but from about 200 countries to nearly 7,000 languages is a long way to go. Of course, the vast majority of languages have very few speakers, making the average of 35 languages per country a misleading calculation. Yet the simple fact remains that most countries―even in Europe and America, the continents with the smallest number of languages―have speakers of more than one language.