Shortleaf Pine Restoration Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

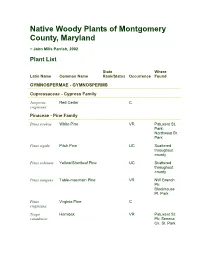

Native Woody Plants of Montgomery County, Maryland

Native Woody Plants of Montgomery County, Maryland ~ John Mills Parrish, 2002 Plant List State Where Latin Name Common Name Rank/Status Occurrence Found GYMNOSPERMAE - GYMNOSPERMS Cupressaceae - Cypress Family Juniperus Red Cedar C virginiana Pinaceae - Pine Family Pinus strobus White Pine VR Patuxent St. Park; Northwest Br. Park Pinus rigida Pitch Pine UC Scattered throughout county Pinus echinata Yellow/Shortleaf Pine UC Scattered throughout county Pinus pungens Table-mountain Pine VR NW Branch Pk; Blockhouse Pt. Park Pinus Virginia Pine C virginiana Tsuga Hemlock VR Patuxent St. canadensis Pk; Seneca Ck. St. Park ANGIOSPERMAE - MONOCOTS Smilacaceae - Catbrier Family Smilax glauca Glaucous Greenbrier C Smilax hispida Bristly Greenbrier UC/R Potomac (syn. S. River & Rock tamnoides) Ck. floodplain Smilax Common Greenbrier C rotundifolia ANGIOSPERMAE - DICOTS Salicaceae - Willow Family Salix nigra Black Willow C Salix Carolina Willow S3 R Potomac caroliniana River floodplain Salix interior Sandbar Willow S1/E VR/X? Plummer's & (syn. S. exigua) High Is. (1902) (S.I.) Salix humilis Prairie Willow R Travilah Serpentine Barrens Salix sericea Silky Willow UC Little Bennett Pk.; NW Br. Pk. (Layhill) Populus Big-tooth Aspen UC Scattered grandidentata across county - (uplands) Populus Cottonwood FC deltoides Myricaceae - Bayberry Family Myrica cerifera Southern Bayberry VR Little Paint Branch n. of Fairland Park Comptonia Sweet Fern VR/X? Lewisdale, peregrina (pers. com. C. Bergmann) Juglandaceae - Walnut Family Juglans cinerea Butternut S2S3 R -

Pinus Echinata Shortleaf Pine

PinusPinus echinataechinata shortleafshortleaf pinepine by Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia One of the most widespread pines of the Eastern United Sates is Pinus echinata, shortleaf pine. Shortleaf pine was identified and named in 1768. The scientific name means a “prickly pine cone tree.” Other common names for shortleaf pine include shortstraw pine, yellow pine, Southern yellow pine, shortleaf yellow pine, Arkansas soft pine, Arkansas pine, and old field pine. Among all the Southern yellow pines it has the greatest range and is most tolerant of a variety of sites. Shortleaf pine grows Southeast of a line between New York and Texas. It is widespread in Georgia except for coastal coun- ties. Note the Georgia range map figure. Pinus echinata is found growing in many mixtures with other pines and hardwoods. It tends to grow on medium to dry, well-drained, infertile sites, as compared with loblolly pine (Pinus taeda). It grows quickly in deep, well-drained areas of floodplains, but cannot tolerate high pH and high calcium concentrations. Compared with other Southern yellow pines, shortleaf is less demanding of soil oxygen content and essential element availability. It grows in Hardiness Zone 6a - 8b and Heat Zone 6-9. The lowest number of Hardiness Zone tends to delineate the Northern range limit and the largest Heat Zone number tends to define the South- ern edge of the range. This native Georgia pine grows in Coder Tree Grow Zone (CTGZ) A-D (a mul- tiple climatic attribute based map), and in the temperature and precipitation cluster based Coder Tree Planting Zone 1-6. -

Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) 321-356 ©Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; Download Unter

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Entomofauna Jahr/Year: 2007 Band/Volume: 0028 Autor(en)/Author(s): Yefremova Zoya A., Ebrahimi Ebrahim, Yegorenkova Ekaterina Artikel/Article: The Subfamilies Eulophinae, Entedoninae and Tetrastichinae in Iran, with description of new species (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) 321-356 ©Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Entomofauna ZEITSCHRIFT FÜR ENTOMOLOGIE Band 28, Heft 25: 321-356 ISSN 0250-4413 Ansfelden, 30. November 2007 The Subfamilies Eulophinae, Entedoninae and Tetrastichinae in Iran, with description of new species (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) Zoya YEFREMOVA, Ebrahim EBRAHIMI & Ekaterina YEGORENKOVA Abstract This paper reflects the current degree of research of Eulophidae and their hosts in Iran. A list of the species from Iran belonging to the subfamilies Eulophinae, Entedoninae and Tetrastichinae is presented. In the present work 47 species from 22 genera are recorded from Iran. Two species (Cirrospilus scapus sp. nov. and Aprostocetus persicus sp. nov.) are described as new. A list of 45 host-parasitoid associations in Iran and keys to Iranian species of three genera (Cirrospilus, Diglyphus and Aprostocetus) are included. Zusammenfassung Dieser Artikel zeigt den derzeitigen Untersuchungsstand an eulophiden Wespen und ihrer Wirte im Iran. Eine Liste der für den Iran festgestellten Arten der Unterfamilien Eu- lophinae, Entedoninae und Tetrastichinae wird präsentiert. Mit vorliegender Arbeit werden 47 Arten in 22 Gattungen aus dem Iran nachgewiesen. Zwei neue Arten (Cirrospilus sca- pus sp. nov. und Aprostocetus persicus sp. nov.) werden beschrieben. Eine Liste von 45 Wirts- und Parasitoid-Beziehungen im Iran und ein Schlüssel für 3 Gattungen (Cirro- spilus, Diglyphus und Aprostocetus) sind in der Arbeit enthalten. -

Introgression Between Pinus Taeda L. and Pinus Echinata Mill

Introgression between Pinus taeda L. and Pinus echinata Mill. Jiwang Chen 1, C. G. Tauer l , Guihua Bai1, and Yinghua Huang1 Key words: cpDNA; introgression; microsatellite; nuclear ribosomal DNA; loblolly pine; shortleaf pine INTRODUCTION Loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.) and shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata Mill.) have widely overlapping geographic ranges. Hybridization between the two species has interested tree breeders for a long time. Morphologically, the two pine species are different. The needles of loblolly pine are 6 to 9 inches long, usually with three yellow-green needles per fascicle; but shortleaf pine needles are 3 to 5 inches long, with two or three dark yellow- green slender and flexible needles per fascicle. Loblolly pine also has larger cones than shortleaf, as well as other differences, however, these characters offer limited help when the genotypes of the parents and their probable hybrids are compounded by environmental factors The limitations of morphological characters resulted in the identification of the allozyme marker IDH (isocitrate dehydrogenase) to identify hybrids (Huneycutt and Askew, 1989). The high frequency of IDH variation seen in natural shortleaf pine populations outside the natural range of loblolly pine (Rajiv et al., 1997) suggests either profuse hybridization between the two species or that IDH is an unreliable marker. These data required us to look for new markers to confirm the identity of putative hybrids. A more extensive study (relative to the study of Rajiv et al., 1997), sampling a larger portion of shortleaf-loblolly pine sympatric population, was conducted to further explore the nature and extent of these hybrids in the native populations. -

Literature Cited

Literature Cited Robert W. Kiger, Editor This is a consolidated list of all works cited in volumes 19, 20, and 21, whether as selected references, in text, or in nomenclatural contexts. In citations of articles, both here and in the taxonomic treatments, and also in nomenclatural citations, the titles of serials are rendered in the forms recommended in G. D. R. Bridson and E. R. Smith (1991). When those forms are abbre- viated, as most are, cross references to the corresponding full serial titles are interpolated here alphabetically by abbreviated form. In nomenclatural citations (only), book titles are rendered in the abbreviated forms recommended in F. A. Stafleu and R. S. Cowan (1976–1988) and F. A. Stafleu and E. A. Mennega (1992+). Here, those abbreviated forms are indicated parenthetically following the full citations of the corresponding works, and cross references to the full citations are interpolated in the list alphabetically by abbreviated form. Two or more works published in the same year by the same author or group of coauthors will be distinguished uniquely and consistently throughout all volumes of Flora of North America by lower-case letters (b, c, d, ...) suffixed to the date for the second and subsequent works in the set. The suffixes are assigned in order of editorial encounter and do not reflect chronological sequence of publication. The first work by any particular author or group from any given year carries the implicit date suffix “a”; thus, the sequence of explicit suffixes begins with “b”. Works missing from any suffixed sequence here are ones cited elsewhere in the Flora that are not pertinent in these volumes. -

Nota Lepidopterologica

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Nota lepidopterologica Jahr/Year: 1992 Band/Volume: Supp_4 Autor(en)/Author(s): Baixeras Joaquin, Dominguez Martin Artikel/Article: Remarks on two species of Tortricidae new to Spain (Lepidoptera) 97-102 ©Societas Europaea Lepidopterologica; download unter http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ und www.zobodat.at Proc. VIL Congr. Eur. Lepid., Lunz 3-8.IX.1990 Nota lepid. Supplement No. 4 : 97-102 ; 30.XI.1992 ISSN 0342-7536 Remarks on two species of Tortricidae new to Spain (Lepidoptera) Joaquin Baixeras & Martin Dominguez, Dpt. Biologia Animal, Bio- logia Cellular i Parasitologia, Universität de Valencia, C/Dr. Moliner, 50. E-46100 Burjassot (Valencia), Spain. Summary Some remarks are given on two species of the family Tortricidae in Spain with particular reference to the fauna of the Iberian Mountains : Selania resedana Obr. and Rhyacionia piniana H.-S. are recorded for the first time from the Iberian Peninsula. Information about their distribution, taxonomy and variability is given. Selania resedana (Obraztsov, 1959) Laspeyresia resedana Obraztsov, 1959, Tijdschr. Ent., 102 : 186, 196-197, figs. 44, 45. Locus typicus : Savona (Liguria, Italia). Selania resedana : Danilevsky & Kuznetsov, 1969, Fauna USSR, Lepidop- tera, 5 (1) : 448-449, fig. 322. Kuznetsov, in Medvedev, 1978, Opredelitel Nasek. 4 (1) : 647, 680, figs. 557 (3), 585 (3). Diakonoff, 1983, Fauna of Saudi Arabia 5 : 256-258, figs. 27-32. 1984- Material examined : Calles, 1984-85, 203 <$<$, 55 ÇÇ Porta-Coeli, 85, 48 33, 33 99. Titaguas, 3 33, 1 9. All the localities in the province of Valencia (Spain). -

Southern Forest Experiment Station Notes on the Life

w ~ r--.~·-OCCASIONAL PAPER NO. 45 APRIL 2, 1935 ~ (Reissue, Feb. 19, 1941) ~ I SOUTHERN FOREST EXPERIMENT STATION ~ ~ E. L. Demmon, Director l\c,, New Orleans, La. NOTES ON THE LIFE CYCLE OF THE NANTUCKET TIP MO'l'H RHYAOIONIA FRUSTRANA COMST. IN SOUTHEASTERN LOUISlANA By Philip C. Wakeley, Associate Silviculturist Southern Forest Experiment Station ...• I The Occasional Papers of the Southern Forest Experiment Station present information on current southern forestry prob lems under investigation at the station. In some cases, these •contributions were first presented as addresses to a limited i group of people, and as "occasional papers 11 they can reach a " much wider audience, In other cases, they are summaries of investigations prepared especially t o give a report of the progress made in a particular field of research. In any case, the statements herein contained should be considered subject to correction or modification as f urther data are obtained. Note: Assistance in the duplication of this paper was furnished by the personnel of Work Projects Administration official project 165-2-64-102. NOTES ON THE LIFE CYCLE OF THE NANTUCKET TIP MOTH RHYACIONIA FRUSTRANA COMST. IN SOUTHEASTERN LOUISIANAY By Philip C. Wakeley, Associate Silviculturist Southern Forest Experiment Station The Nantucket tip moth (RhYacionia frustrana Comst.) is a small tor tricid moth occurring generally throughout the pine forests of North America. The larvae are responsible for an immense amount of dam~ge to small pines, both in natural reproduction and in planted stands OJ .9 In 1915, W.R. Mattoon, of the United States Forest Service, described the conspicuous damage of the Nantucket tip moth on shortleaf pine (Pinus e'china.ta) in the South (2), but somewhat underrated the potentialities of the insect for mischief. -

Pheromone-Based Disruption of Eucosma Sonomana and Rhyacionia Zozana (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) Using Aerially Applied Microencapsulated Pheromone1

361 Pheromone-based disruption of Eucosma sonomana and Rhyacionia zozana (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) using aerially applied microencapsulated pheromone1 Nancy E. Gillette, John D. Stein, Donald R. Owen, Jeffrey N. Webster, and Sylvia R. Mori Abstract: Two aerial applications of microencapsulated pheromone were conducted on five 20.2 ha plots to disrupt western pine shoot borer (Eucosma sonomana Kearfott) and ponderosa pine tip moth (Rhyacionia zozana (Kearfott); Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) orientation to pheromones and oviposition in ponderosa pine plantations in 2002 and 2004. The first application was made at 29.6 g active ingredient (AI)/ha, and the second at 59.3 g AI/ha. Baited sentinel traps were used to assess disruption of orientation by both moth species toward pheromones, and E. sonomana infes- tation levels were tallied from 2001 to 2004. Treatments disrupted orientation by both species for several weeks, with the first lasting 35 days and the second for 75 days. Both applications reduced infestation by E. sonomana,but the lower application rate provided greater absolute reduction, perhaps because prior infestation levels were higher in 2002 than in 2004. Infestations in treated plots were reduced by two-thirds in both years, suggesting that while increas- ing the application rate may prolong disruption, it may not provide greater proportional efficacy in terms of tree pro- tection. The incidence of infestations even in plots with complete disruption suggests that treatments missed some early emerging females or that mated females immigrated into treated plots; thus operational testing should be timed earlier in the season and should comprise much larger plots. In both years, moths emerged earlier than reported pre- viously, indicating that disruption programs should account for warmer climates in timing of applications. -

![SHORTLEAF PINE [Pinaceae] Pinus Echinata Miller](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6490/shortleaf-pine-pinaceae-pinus-echinata-miller-586490.webp)

SHORTLEAF PINE [Pinaceae] Pinus Echinata Miller

Vascular Plants of Williamson County Pinus echinata − SHORTLEAF PINE [Pinaceae] Pinus echinata Miller (possible selection, mixed-sized plants in woodland of escaped plants originating from cultivated specimens), SHORTLEAF PINE. Tree, evergreen, with 1 trunk to 30 cm diameter (non-cultivated), in range 4−10 m tall (reproductive); monoecious; shoots with long shoot-short shoot organization, long shoot growth beginning in late March, with closely spaced, nonphotosynthetic scale leaves along new axis (new spring growth after pollination begins), springtime long shoot initially to 200 × 8 mm before foliage leaf elongating, at each node having a scalelike primary leaf but immediately producing a short shoot in the axil of scale leaf (sylleptic development) = a “fascicle” of 2−3 photosynthetic leaves (needles) held together by several tightly wrapped papery (scarious) leaves at the base, glabrous, having resin ducts within plant, aromatic, especially when crushed or damaged. Stems: internodes relatively short hidden by persistent bases of scale leaves; young twigs flexible, lacking leaves when > 4 mm diameter, with helically arranged remnants of scale leaves; older stems with woody seed cones mostly 7−8 mm diameter shedding tannish gray leaf bases and forming light brown periderm; bark large- scaly, not peeling and tightly attached, gray, not obviously resinous. Leaves: of 3 types (scale, foliage, wrapper); scale leaves on new long shoots helically alternate, simple, sessile with decurrent bases; foliage leaves (needles) terminal and mostly -

Natural Piedmont Forests

Spring 2009 Guide to Delaware Vegetation Communities Robert Coxe Guide to Delaware Vegetation Communities-Spring 2009 Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge the contributions and help from the following people for this edition of the Guide to Delaware Vegetation Communities. Karen Bennett, Greg Moore and Janet Dennis of the Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife Bill McAvoy of the Delaware Natural Heritage Program Dr. John Kartesz of the Biota of North America Program Dr. Keith Clancy and Pete Bowman, Ecologists, formerly of the Delaware Natural Heritage Program Ery Largay and Leslie Sneddon of Natureserve All people unmentioned who made countless contributions to this document. -Take me to the vegetation community keys- Guide to Delaware Vegetation Communities-Spring 2009 Introduction The Guide to Delaware Vegetation Communities is intended to provide a Delaware flavor to the National Vegetation Classification System (NVCS). All common names of communities, except for those not in the NVCS, follow the NVCS. This document is designed for the web and CD only, but desired sections can be printed by users. In this matter, paper and therefore trees can be preserved and impacts to the communities discussed within can be minimized. In spirit of saving these communities please only print those community descriptions that you will use or print none at all. The State of Delaware covers 1,524,863.4 acres of which 1,231,393.6 acres are terrestrial and 293,469.8 acres are water (Table 1). Currently 130 vegetation communities are known to occur in Delaware. Some of the largest vegetation communities/land covers in the state include: Table 1. -

Alabama Forestry Invitational State Manual & Study Guide

Alabama Forestry Invitational State Manual & Study Guide The Alabama Cooperative Extension System (Alabama A&M University and Auburn University) is an equal opportunity educator and employer. Everyone is welcome! Please let us know if you have accessibility needs. © 2020 by the Alabama Cooperative Extension System. All rights reserved. www.aces.edu 4HYD-2426 Alabama Cooperative Extension System Mission Statement The Alabama Cooperative Extension System, the primary outreach organization for the land grant mission of Alabama A&M University and Auburn University, delivers research-based educational programs that enable people to improve their quality of life and economic well-being. ALABAMA 4-H VISION Alabama 4-H is an innovative, responsive leader in developing youth to be productive citizens and leaders in a complex and dynamic society. Our vision is supported through the collaborative, committed efforts of Extension professionals, youth, and volunteers. ALABAMA 4-H MISSION 4-H is the youth development component of the Alabama Cooperative Extension System. 4-H helps young people from rural and urban areas explore their interests and expand their awareness of our world while providing opportunities to develop a greater sense of who they are and who they can become–as contributing citizens of our communities, our state, our nation, and our world. This mission is achieved through research-based educational programs of Alabama A&M and Auburn Universities and an ongoing tradition of applied, hands-on/minds-on experiences, which develop the heads, hearts, hands, and health of Alabama youth. 4-H is a community of young people across Alabama who are learning leadership, citizenship, and life skills. -

Panflora Site Plant List Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve (TNC) Generated: 7 June 2005 Copyright: Gil Nelson 186 Records

PanFlora Site Plant List Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve (TNC) Generated: 7 June 2005 Copyright: Gil Nelson 186 Records Acer negundo (BOXELDER) Acer rubrum (RED MAPLE) Aesculus pavia (RED BUCKEYE) Agalinis divaricata (PINELAND FALSE FOXGLOVE) Albizia julibrissin (MIMOSA) Amelanchier arborea (COMMON SERVICEBERRY) Arenaria lanuginosa (SPREADING SANDWORT) Arenaria serpyllifolia (THYMELEAF SANDWORT) Arisaema dracontium (GREENDRAGON) Arisaema quinatum (PESTER-JOHN) Arisaema triphyllum (JACK-IN-THE-PULPIT) Aristida stricta beyrichiana (WIREGRASS) Aristolochia serpentaria (VIRGINIA SNAKEROOT) Aristolochia tomentosa (WOOLLY DUTCHMAN'S-PIPE; PIPEVINE) Arundinaria gigantea (SWITCHCANE) Asarum arifolium (WILD GINGER; LITTLE BROWN JUG; HEARTLEAF WILD GINGER) Asimina parviflora (SMALLFLOWER PAWPAW) Asplenium platyneuron (EBONY SPLEENWORT) Athyrium filix-femina asplenioides (SOUTHERN LADY FERN) Aureolaria flava (SMOOTH YELLOW FALSE FOXGLOVE) Baptisia lanceolata (GOPHERWEED) Berlandiera pumila (SOFT GREENEYES) Betula nigra (RIVER BIRCH) Bignonia capreolata (CROSSVINE) Boechera canadensis (SICKLEPOD) Calamintha dentata (FLORIDA CALAMINT; TOOTHED SAVORY) Callicarpa americana (AMERICAN BEAUTYBERRY) Calycanthus floridus (EASTERN SWEETSHRUB; CAROLINA ALLSPICE) Calycocarpum lyonii (CUPSEED) Carex baltzellii (BALTZELL'S SEDGE) Carex digitalis (SLENDER WOODLAND SEDGE) Carex nigromarginata floridana (BLACKEDGE SEDGE) Carpinus caroliniana (AMERICAN HORNBEAM; BLUEBEECH) Carya glabra (PIGNUT HICKORY) Carya pallida (SAND HICKORY) Ceanothus microphyllus (LITTLELEAF