The Garden of Perfect Brightness: a Life in Ruins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Goldman Sachs Guide to Beijing

GOLDMAN SACHS: The GS Guide to Beijing Opened in 1994, the Goldman Sachs Beijing office was our first in China – marking the beginning of a permanent presence on the mainland Our offices are in Winland International center, 18th Floor, 7 Finance Street Beijing is the nation’s political, cultural and educational center The city is built to a square layout. Locals prefer to use ‘go east/west/north/south’ when giving directions, instead of ‘turn right/left’ Bring our kids to work day is usually close to Halloween and our children will ‘trick or treat’ in the office Beijing city experiences the winter season from late November and lasts for about 100 days. Beautiful snow scenes are created when snow falls on the cityscapes and nearby mountains Finance Street is our favorite spot for a walking meeting or outside lunch Quotes: − “The best thing about living in our city? Dynamic neighborhoods mixing traditional histories and modern vibes” – Mandy, Executive Office − “The Fuchengmen Subway Line 2 is about a 5 minute walk from the office. This is really convenient and helps avoid traffic jams during rush hours” – Anna, Operations − “The best things about our city: traditional food, the snowfall, and Hutong – narrow streets and alleys commonly associated with Chinese cities” – Weihong, Engineering Our Favorite Parks Are: − Summer Palace − The Temple of Heaven Our Favorite Landmarks: − Forbidden City − National Museum − White Pagoda − Great Wall of China Festivals and Cultural Traditions: − Peking Opera − Chinese New Year − Traditional Beijing Hotpot Cuisine − Moon Festival See yourself here. Click the apply button on our students or professionals pages to explore opportunities in Beijing and around the world . -

China's 1911 Revolution

www.hoddereducation.co.uk/historyreview Volume 23, Number 1, September 2020 Revision China’s 1911 Revolution Nicholas Fellows Test your knowledge of the 1911 Revolution in China and the events preceding it with these multiple-choice questions. Answers on the final page Questions 1 When did the First Opium War start? 1837 1838 1839 1840 2 What term was used to describe the agreements China was forced to sign with the West following its defeat? Unfair Treaties Unequal Treaties Concession Treaties Compromise Treaties 3 Which dynasty ruled china at the time of the Opium Wars? Ming Qing Yuan Song 4 When did the Second Opium War start? 1856 1857 1858 1859 5 What event started the war? Macartney incident Beijing affair Dagu Fort clash Arrow Incident 6 Which country destroyed a Chinese fleet in Fuzhou in 1884? Britain Germany France Spain 7 Which country took Korea from China in 1894? France Japan Britain Russia 8 Which country occupied much of Manchuria? Russia Japan Britain France 9 Which country took the port of Weihaiwei? Russia Japan Britain France 10 When did the Boxer rising start? 1899 1900 1901 1902 11 What provoked the start of the Boxer Rising? Loss of land Increase in the opium trade Western missionaries Development of railways Hodder & Stoughton © 2019 www.hoddereducation.co.uk/historyreview www.hoddereducation.co.uk/historyreview 12 Whose ambassador was shot at the start of the rising? German French British Russian 13 Who wrote 'The Revolutionary Army' in 1903 Sun Yat-sen Zou Rong Li Hongzhang Lu Xun 14 Who organised the Revolutionary -

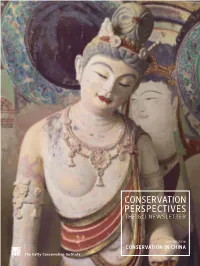

Conservation in China Issue, Spring 2016

SPRING 2016 CONSERVATION IN CHINA A Note from the Director For over twenty-five years, it has been the Getty Conservation Institute’s great privilege to work with colleagues in China engaged in the conservation of cultural heritage. During this quarter century and more of professional engagement, China has undergone tremendous changes in its social, economic, and cultural life—changes that have included significant advance- ments in the conservation field. In this period of transformation, many Chinese cultural heritage institutions and organizations have striven to establish clear priorities and to engage in significant projects designed to further conservation and management of their nation’s extraordinary cultural resources. We at the GCI have admiration and respect for both the progress and the vision represented in these efforts and are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage in China. The contents of this edition of Conservation Perspectives are a reflection of our activities in China and of the evolution of policies and methods in the work of Chinese conservation professionals and organizations. The feature article offers Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI a concise view of GCI involvement in several long-term conservation projects in China. Authored by Neville Agnew, Martha Demas, and Lorinda Wong— members of the Institute’s China team—the article describes Institute work at sites across the country, including the Imperial Mountain Resort at Chengde, the Yungang Grottoes, and, most extensively, the Mogao Grottoes. Integrated with much of this work has been our participation in the development of the China Principles, a set of national guide- lines for cultural heritage conservation and management that respect and reflect Chinese traditions and approaches to conservation. -

The Curious Double-Life of Putuoshan As Monastic Centre and Commercial Emporium, 1684–1728 113 ©2021 by RCHSS, Academia Sinica

Journal of Social Sciences and Philosophy Volume 33, Number 1, pp. 113–140 The Curious Double-Life of Putuoshan as Monastic Centre and Commercial Emporium, 1684–1728 113 ©2021 by RCHSS, Academia Sinica. All rights reserved. The Curious Double-Life of Putuoshan as Monastic Centre and Commercial Emporium, 1684–1728✽ Ryan Holroyd✽✽ Postdoctoral Research Associate Center for Asia-Pacific Area Studies, Research Center for Humanities and Social Sciences, Academia Sinica ABSTRACT This article investigates how the island of Putuoshan simultaneously acted as a Buddhist monastic centre and a maritime shipping hub from the Qing dynasty’s legalisation of overseas trade in 1684 until the 1720s. It argues that because overseas trade during the Kangxi era was inconsistently regulated, a mutually beneficial relationship developed between Putuoshan’s Buddhist mon- asteries, the merchants who sailed between China and Japan, and the regional naval commanders on Zhoushan. Instead of forcing merchant vessels to enter ports with customs offices, the naval commanders allowed merchants to use Putuoshan’s harbour, which lay beyond the empire’s trade administration system. The monasteries enjoyed the patronage of the merchants, and so rewarded the naval commanders by publicly honouring them. However, a reorganisation of the empire’s customs system in the mid–1720s shifted the power over trade to Zhejiang’s governor general, who brought an end to Putuoshan’s special status outside the administration around 1728. Key Words: maritime trade, Qing dynasty, Putuoshan, Buddhist history ✽I would like to express my gratitude to Liu Shiuh-Feng, Wu Hsin-fang, Su Shu-Wei, and the two anonymous reviewers of my paper for taking the time to read it and for offering patient and helpful advice. -

Sino-US Relations and Ulysses S. Grant's Mediation

Looking for a Friend: Sino-U.S. Relations and Ulysses S. Grant’s Mediation in the Ryukyu/Liuqiu 琉球 Dispute of 1879 Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad Michael Berry Graduate Program in East Asian Studies The Ohio State University 2014 Thesis Committee: Christopher A. Reed, Advisor Robert J. McMahon Ying Zhang Copyright by Chad Michael Berry 2014 Abstract In March 1879, Japan announced the end of the Ryukyu (Liuqiu) Kingdom and the establishment of Okinawa Prefecture in its place. For the previous 250 years, Ryukyu had been a quasi-independent tribute-sending state to Japan and China. Following the arrival of Western imperialism to East Asia in the 19th century, Japan reacted to the changing international situation by adopting Western legal standards and clarifying its borders in frontier areas such as the Ryukyu Islands. China protested Japanese actions in Ryukyu, though Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) leaders were not willing to go to war over the islands. Instead, Qing leaders such as Li Hongzhang (1823-1901) and Prince Gong (1833-1898) sought to resolve the dispute through diplomatic means, including appeals to international law, rousing global public opinion against Japan, and, most significantly, requesting the mediation of the United States and former U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885). Initially, China hoped Grant’s mediation would lead to a restoration of the previous arrangement of Ryukyu being a dually subordinate kingdom to China and Japan. In later negotiations, China sought a three-way division of the islands among China, Japan, and Ryukyu. -

Beijing Subway Map

Beijing Subway Map Ming Tombs North Changping Line Changping Xishankou 十三陵景区 昌平西山口 Changping Beishaowa 昌平 北邵洼 Changping Dongguan 昌平东关 Nanshao南邵 Daoxianghulu Yongfeng Shahe University Park Line 5 稻香湖路 永丰 沙河高教园 Bei'anhe Tiantongyuan North Nanfaxin Shimen Shunyi Line 16 北安河 Tundian Shahe沙河 天通苑北 南法信 石门 顺义 Wenyanglu Yongfeng South Fengbo 温阳路 屯佃 俸伯 Line 15 永丰南 Gonghuacheng Line 8 巩华城 Houshayu后沙峪 Xibeiwang西北旺 Yuzhilu Pingxifu Tiantongyuan 育知路 平西府 天通苑 Zhuxinzhuang Hualikan花梨坎 马连洼 朱辛庄 Malianwa Huilongguan Dongdajie Tiantongyuan South Life Science Park 回龙观东大街 China International Exhibition Center Huilongguan 天通苑南 Nongda'nanlu农大南路 生命科学园 Longze Line 13 Line 14 国展 龙泽 回龙观 Lishuiqiao Sunhe Huoying霍营 立水桥 Shan’gezhuang Terminal 2 Terminal 3 Xi’erqi西二旗 善各庄 孙河 T2航站楼 T3航站楼 Anheqiao North Line 4 Yuxin育新 Lishuiqiao South 安河桥北 Qinghe 立水桥南 Maquanying Beigongmen Yuanmingyuan Park Beiyuan Xiyuan 清河 Xixiaokou西小口 Beiyuanlu North 马泉营 北宫门 西苑 圆明园 South Gate of 北苑 Laiguangying来广营 Zhiwuyuan Shangdi Yongtaizhuang永泰庄 Forest Park 北苑路北 Cuigezhuang 植物园 上地 Lincuiqiao林萃桥 森林公园南门 Datunlu East Xiangshan East Gate of Peking University Qinghuadongluxikou Wangjing West Donghuqu东湖渠 崔各庄 香山 北京大学东门 清华东路西口 Anlilu安立路 大屯路东 Chapeng 望京西 Wan’an 茶棚 Western Suburban Line 万安 Zhongguancun Wudaokou Liudaokou Beishatan Olympic Green Guanzhuang Wangjing Wangjing East 中关村 五道口 六道口 北沙滩 奥林匹克公园 关庄 望京 望京东 Yiheyuanximen Line 15 Huixinxijie Beikou Olympic Sports Center 惠新西街北口 Futong阜通 颐和园西门 Haidian Huangzhuang Zhichunlu 奥体中心 Huixinxijie Nankou Shaoyaoju 海淀黄庄 知春路 惠新西街南口 芍药居 Beitucheng Wangjing South望京南 北土城 -

Missionaries and the Beginnings of Western Music in China: the Catholic Prelude, 1294-1799

MISSIONARIES AND THE BEGINNINGS OF WESTERN MUSIC IN CHINA: THE CATHOLIC PRELUDE, 1294-1799 By Hongyu GONG Unitec Institute of Technology, New Zealand Next to the Word of God, only music deserves being extolled as the mistress and governess of the feelings of the human heart. — Martin Luther (1538)1 he history of modern China is closely intertwined with the global expansion of TChristianity.2 The Protestant movement of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in particular, as some scholars have convincingly argued, had played an important part in China’s search for modernity.3 No other agents of Western influence managed to achieve the kind of 1 Cited in Walter E. Buszin, “Luther on Music”, The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 32, No. 1 (1946), p. 81. 2 Rather than following the accepted Chinese scheme of periodization, which starts with the Opium War of 1839, here the term modern China refers to China since the late Ming, as used in Jonathan D. Spence’s The Search for Modern China (New York & London: W. W. Norton & Company, 1990). 3 The roles played by Christian missionaries in China’s search for modernity have been studied by a number of scholars both in China and abroad. For recent studies in Chinese, see Gu Changsheng/頋長 聲, Chuanjiaoshi yu jindai Zhongguo/《傳教士與近代中國》/Missionaries and Modern China (Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe, 1991); Shi Jinghuan/史静寰 and Wang Lixin/王立新, Jidujiao jiaoyu yu Zhongguo zhishi fenzi/《基督教教育與中國知識分子》/Christian Education and Chinese Intellectuals (Fuzhou: Fujian jiaoyu chubanshe, 1998). For an excellent overall survey of China missions during the ISSN 1092-1710, Journal of Music in China, vol. -

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction The name Shanghai still conjures images of romance, mystery and adventure, but for decades it was an austere backwater. After the success of Mao Zedong's communist revolution in 1949, the authorities clamped down hard on Shanghai, castigating China's second city for its prewar status as a playground of gangsters and colonial adventurers. And so it was. In its heyday, the 1920s and '30s, cosmopolitan Shanghai was a dynamic melting pot for people, ideas and money from all over the planet. Business boomed, fortunes were made, and everything seemed possible. It was a time of breakneck industrial progress, swaggering confidence and smoky jazz venues. Thanks to economic reforms implemented in the 1980s by Deng Xiaoping, Shanghai's commercial potential has reemerged and is flourishing again. Stand today on the historic Bund and look across the Huangpu River. The soaring 1,614-ft/492-m Shanghai World Financial Center tower looms over the ambitious skyline of the Pudong financial district. Alongside it are other key landmarks: the glittering, 88- story Jinmao Building; the rocket-shaped Oriental Pearl TV Tower; and the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The 128-story Shanghai Tower is the tallest building in China (and, after the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the second-tallest in the world). Glass-and-steel skyscrapers reach for the clouds, Mercedes sedans cruise the neon-lit streets, luxury- brand boutiques stock all the stylish trappings available in New York, and the restaurant, bar and clubbing scene pulsates with an energy all its own. Perhaps more than any other city in Asia, Shanghai has the confidence and sheer determination to forge a glittering future as one of the world's most important commercial centers. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

A Case Study of the Chinese Repository

Durham E-Theses Orientalism and Representations of China in the Early 19th Century: A Case Study of The Chinese Repository JIN, CHENG How to cite: JIN, CHENG (2019) Orientalism and Representations of China in the Early 19th Century: A Case Study of The Chinese Repository, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13227/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ORIENTALISM AND REPRESENTATIONS OF CHINA IN THE EARLY 19TH CENTURY: A CASE STUDY OF THE CHINESE REPOSITORY Cheng Jin St. Cuthbert’s Society School of Modern Languages and Cultures Durham University This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2019 March 2019 DECLARATION This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing, which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. -

The Interaction Between Ethnic Relations and State Power: a Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Georgia State University Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Sociology Dissertations Department of Sociology 5-27-2008 The nI teraction between Ethnic Relations and State Power: A Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911 Wei Li Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Li, Wei, "The nI teraction between Ethnic Relations and State Power: A Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2008. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss/33 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Sociology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INTERACTION BETWEEN ETHNIC RELATIONS AND STATE POWER: A STRUCTURAL IMPEDIMENT TO THE INDUSTRIALIZATION OF CHINA, 1850-1911 by WEI LI Under the Direction of Toshi Kii ABSTRACT The case of late Qing China is of great importance to theories of economic development. This study examines the question of why China’s industrialization was slow between 1865 and 1895 as compared to contemporary Japan’s. Industrialization is measured on four dimensions: sea transport, railway, communications, and the cotton textile industry. I trace the difference between China’s and Japan’s industrialization to government leadership, which includes three aspects: direct governmental investment, government policies at the macro-level, and specific measures and actions to assist selected companies and industries. -

Pagodas & Pavilions

Pagodas & Pavilions China Itinerary Beijing (4), Xi’an (2), Option Shanghai (2) DAY 1 Board your flight and journey to China, crossing traditional China as pictured in silk-screen prints. the International Dateline. DAY 6 XI’AN Fly to Xi’an, the great ancient capital and DAY 2 BEIJING Welcome to the fascinating and the eastern end of the Silk Road, the main trade route ancient land of China! Arrive in the capital city of Beijing between China, central Asia and Europe. Upon arrival, and transfer to your hotel. Relax, unpack and prepare for enjoy a Xi’an City Tour. See the eight mile long ancient a fabulous week in the world’s most populous country, city wall, the Bell Tower, the Drum Tower and other the “country of the dragon.” highlights. Visit the 7-story Big Wild Goose Pagoda in Highlights DAY 3 BEIJING Explore the magnificent Temple of the Ci’en Temple. • Temple of Heaven Heaven, an architectural wonder built entirely without DAY 7 XI’AN The accidental discovery of the gigantic • Beijing City nails. The building’s shapes, colors, and materials all tomb of the first emperor, Qin Shinhuang, revealed the have a special purpose and meaning. This was the aspiration of the king who attempted to perpetuate his • Tour site where the Emperors conducted their most sacred power to the afterlife. Visit the Horse Museum where • Great Wall rituals. The walled park offers you a chance to view the over 7,000 life-size Terra Cotta Warriors and their horses Chinese at play, since many families practice Tai Chi, guard have been guarding the emperor’s tomb for • Ming Tombs juggle, exercise, dance, and picnic here.