Transient Global Amnesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psychogenic and Organic Amnesia. a Multidimensional Assessment of Clinical, Neuroradiological, Neuropsychological and Psychopathological Features

Behavioural Neurology 18 (2007) 53–64 53 IOS Press Psychogenic and organic amnesia. A multidimensional assessment of clinical, neuroradiological, neuropsychological and psychopathological features Laura Serraa,∗, Lucia Faddaa,b, Ivana Buccionea, Carlo Caltagironea,b and Giovanni A. Carlesimoa,b aFondazione IRCCS Santa Lucia, Roma, Italy bClinica Neurologica, Universita` Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy Abstract. Psychogenic amnesia is a complex disorder characterised by a wide variety of symptoms. Consequently, in a number of cases it is difficult distinguish it from organic memory impairment. The present study reports a new case of global psychogenic amnesia compared with two patients with amnesia underlain by organic brain damage. Our aim was to identify features useful for distinguishing between psychogenic and organic forms of memory impairment. The findings show the usefulness of a multidimensional evaluation of clinical, neuroradiological, neuropsychological and psychopathological aspects, to provide convergent findings useful for differentiating the two forms of memory disorder. Keywords: Amnesia, psychogenic origin, organic origin 1. Introduction ness of the self – and a period of wandering. According to Kopelman [33], there are three main predisposing Psychogenic or dissociative amnesia (DSM-IV- factors for global psychogenic amnesia: i) a history of TR) [1] is a clinical syndrome characterised by a mem- transient, organic amnesia due to epilepsy [52], head ory disorder of nonorganic origin. Following Kopel- injury [4] or alcoholic blackouts [20]; ii) a history of man [31,33], psychogenic amnesia can either be sit- psychiatric disorders such as depressed mood, and iii) uation specific or global. Situation specific amnesia a severe precipitating stress, such as marital or emo- refers to memory loss for a particular incident or part tional discord [23], bereavement [49], financial prob- of an incident and can arise in a variety of circum- lems [23] or war [21,48]. -

Episodic Memory in Transient Global Amnesia: Encoding, Storage, Or Retrieval Deficit?

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.148 on 1 February 1999. Downloaded from 148 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999;66:148–154 Episodic memory in transient global amnesia: encoding, storage, or retrieval deficit? Francis Eustache, Béatrice Desgranges, Peggy Laville, Bérengère Guillery, Catherine Lalevée, Stéphane SchaeVer, Vincent de la Sayette, Serge Iglesias, Jean-Claude Baron, Fausto Viader Abstract evertheless this division into processing stages Objectives—To assess episodic memory continues to be useful in helping understand (especially anterograde amnesia) during the working of memory systems”. These three the acute phase of transient global amne- stages may be defined in the following way: (1) sia to diVerentiate an encoding, a storage, encoding, during which perceptive information or a retrieval deficit. is transformed into more or less stable mental Methods—In three patients, whose am- representations; (2) storage (or consolidation), nestic episode fulfilled all current criteria during which mnemonic information is associ- for transient global amnesia, a neuro- ated with other representations and maintained psychological protocol was administered in long term memory; (3) retrieval, during which included a word learning task which the subject can momentarily reactivate derived from the Grober and Buschke’s mnemonic representations. These definitions procedure. will be used in the present study. Results—In one patient, the results sug- Regarding the retrograde amnesia of TGA, it gested an encoding deficit, -

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory John Dunlosky and Robert A. Bjork Introduction Memory has been of interest to scholars and laypeople alike for over 2,000 years. In a rather gruesome example from antiquity, Cicero tells the story of Simonides (557– 468 BC), who discovered the method of loci, which is a powerful mental mnemonic for enhancing one’s memory. Simonides was at a banquet of a nobleman, Scopas. To honor him, Simonides sang a poem, but to Scopas’s chagrin, the poem also honored two young men, Castor and Pollux. Being upset, Scopas told Simonides that he was to receive only half his wage. Simonides was later called from the banquet, and legend has it that the banquet room collapsed, and all those inside were crushed. To help bereaved families identify the victims, Simonides reportedly was able to name every- one according to the place where they sat at the table, which gave him the idea that order brings strength to our memories and that to employ this ability people “should choose localities, then form mental images of things they wanted to store in their memory, and place these in the localities” (Cicero, 2001). Tis example highlights an early discovery that has had important applied impli- cations for improving the functioning of memory (see, e.g., Yates, 1997). Memory theory was soon to follow. Aristotle (385–322 BC) claimed that memory arises from three processes: Events are associated (1) through their relative similarity or (2) rela- tive dissimilarity and (3) when they co-occur together in space and time. -

Investigating the Roles of Memory and Metamemory in Trauma-Related Outcomes

ABSTRACT A PTSD ANALOGUE STUDY: INVESTIGATING THE ROLES OF MEMORY AND METAMEMORY IN TRAUMA-RELATED OUTCOMES Ban Hong (Phylice) Lim, Ph.D. Department of Psychology Northern Illinois University, 2016 Michelle M. Lilly, Director Trauma survivors who develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often display symptoms of memory fragmentation such as an impaired ability to recall trauma memories. These observations are consistent with prominent theories of PTSD, which consider memory fragmentation as a central feature of PTSD. Correspondingly, most empirically supported interventions for PTSD focus on addressing dysfunctional thoughts and behaviors and integrating fragmented memories of the event. More recently, this assumption has been challenged by research indicating that metamemory – one’s subjective beliefs about one’s memory functioning and quality – may partially account for reported memory fragmentation among individuals with PTSD. Memory underconfidence, regardless of whether or not it is founded or wholly accurate, may lead to feelings of anxiety, especially in the process of recalling and making sense of one’s trauma memory. Despite the intertwined nature of their relationship, the association between memory and metamemory has been understudied in the trauma literature. This dissertation investigated whether PTSD is a disorder of memory fragmentation, perceived memory fragmentation, or both by examining the association between memory and metamemory. A trauma analogue between-subjects experimental design was employed. Eighty- four healthy participants were randomly assigned to receive either positive feedback or negative feedback after completing a standardized memory assessment. Despite the use of randomization, the manipulation groups systematically differed on both baseline memory ability and baseline memory confidence. Contrary to the first hypothesis, after controlling for the effect of baseline metamemory beliefs, the groups did not differ on their recall task performance, F(1,80) = .34, p = .56. -

DO AMNESICS EXHIBIT COGNITIVE DISSONANCE REDUCTION? the Role of Explicit Memory and Attention in Attitude Change Matthew D

PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Research Article DO AMNESICS EXHIBIT COGNITIVE DISSONANCE REDUCTION? The Role of Explicit Memory and Attention in Attitude Change Matthew D. Lieberman, Kevin N. Ochsner, Daniel T. Gilbert, and Daniel L. Schacter Harvard University Abstract—In two studies, we investigated the roles of explicit mem- CONSCIOUS CONTENT: THE ROLE OF ory and attentional resources in the process of behavior-induced atti- EXPLICIT MEMORY tude change. Although most theories of attitude change (cognitive Explicit memory refers to one’s ability to consciously recollect dissonance and self-perception theories) assume an important role for past events, behaviors, and experiences (Schacter, Chiu, & Ochsner, both mechanisms, we propose that behavior-induced attitude change 1993) and thus is a central component of most social abilities. Indeed, can be a relatively automatic process that does not require explicit people’s memory for the identities and actions of other people and memory for, or consciously controlled processing of, the discrepancy themselves forms the adhesive that gives them a continuing sense of between attitude and behavior. Using a free-choice paradigm, we place in their social world. Revising personal attitudes and beliefs in found that both amnesics and normal participants under cognitive response to a counterattitudinal behavior naturally seems to depend on load showed as much attitude change as did control participants. retrospective capacities. If Aesop’s forlorn lover of grapes could not remember that the grapes were out of reach, he would have no reason A fox saw some ripe black grapes hanging from a trellised vine. He resorted to to persuade himself of their reduced quality. -

Behavioural and Neural Correlates of Individual Differences in Episodic

Behavioural and Neural Correlates of Individual Differences in Episodic Memory by Daniela Jesseca Palombo A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Psychology University of Toronto © Copyright by Daniela Jesseca Palombo, 2013 Behavioural and Neural Correlates of Individual Differences in Episodic Memory Daniela Jesseca Palombo Doctor of Philosophy Department of Psychology University of Toronto 2013 Abstract Episodic autobiographical memory (AM) refers to the real-life recollection of personal events that are contextually-bound to a particular time and place. Anecdotally, individuals differ widely in their ability to remember these types of experiences, yet little cognitive neuroscience research exists to support this idea. By contrast, there is a growing body of literature demonstrating that individual differences in episodic memory for laboratory experiences, intended to serve as a proxy for real life, are associated with brain-biomarkers. The present studies provide a starting point for exploring individual differences in the real-life expression of memory; which is more complex, multifaceted and has longer retention intervals, than laboratory memory (LM), thus allowing for the assessment of remote memory. While there are many factors that contribute to individual differences in episodic AM, the focus of this dissertation is on genetic influences. In particular, the KIBRA gene has been associated with episodic LM in a replicated genome- wide association study; T-carriers showing enhanced performance relative to individuals who lack this allele. The present series of studies explored the association of KIBRA with ii episodic AM. An ancillary goal was to clarify the association between KIBRA and episodic LM. -

PAVOL JOZEF ŠAFARIK UNIVERSITY in KOŠICE Dissociative Amnesia: a Clinical and Theoretical Reconsideration DEGREE THESIS

PAVOL JOZEF ŠAFARIK UNIVERSITY IN KOŠICE FACULTY OF MEDICINE Dissociative amnesia: a clinical and theoretical reconsideration Paulo Alexandre Rocha Simão DEGREE THESIS Košice 2017 PAVOL JOZEF ŠAFARIK UNIVERSITY IN KOŠICE FACULTY OF MEDICINE FIRST DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHIATRY Dissociative amnesia: a clinical and theoretical reconsideration Paulo Alexandre Rocha Simão DEGREE THESIS Thesis supervisor: Mgr. MUDr. Jozef Dragašek, PhD., MHA Košice 2017 Analytical sheet Author Paulo Alexandre Rocha Simão Thesis title Dissociative amnesia: a clinical and theoretical reconsideration Language of the thesis English Type of thesis Degree thesis Number of pages 89 Academic degree M.D. University Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice Faculty Faculty of Medicine Department/Institute Department of Psychiatry Study branch General Medicine Study programme General Medicine City Košice Thesis supervisor Mgr. MUDr. Jozef Dragašek, PhD., MHA Date of submission 06/2017 Date of defence 09/2017 Key words Dissociative amnesia, dissociative fugue, dissociative identity disorder Thesis title in the Disociatívna amnézia: klinické a teoretické prehodnotenie Slovak language Key words in the Disociatívna amnézia, disociatívna fuga, disociatívna porucha identity Slovak language Abstract in the English language Dissociative amnesia is a one of the most intriguing, misdiagnosed conditions in the psychiatric world. Dissociative amnesia is related to other dissociative disorders, such as dissociative identity disorder and dissociative fugue. Its clinical features are known -

Paranoid Or Bizarre Delusions, Or Disorganized Speech and Thinking, and It Is Accompanied by Significant Social Or Occupational Dysfunction

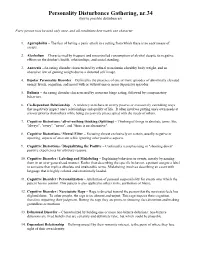

Personality Disturbance Gathering, nr.34 (key to possible disturbances) Every person may be used only once, and all conditions best match one character. 1. Agoraphobia – The fear of having a panic attack in a setting from which there is no easy means of escape. 2. Alcoholism – Characterized by frequent and uncontrolled consumption of alcohol despite its negative effects on the drinker's health, relationships, and social standing. 3. Anorexia –An eating disorder characterized by refusal to maintain a healthy body weight, and an obsessive fear of gaining weight due to a distorted self image. 4. Bipolar Personality Disorder – Defined by the presence of one or more episodes of abnormally elevated energy levels, cognition, and mood with or without one or more depressive episodes. 5. Bulimia – An eating disorder characterized by recurrent binge eating, followed by compensatory behaviors. 6. Co-Dependant Relationship – A tendency to behave in overly passive or excessively caretaking ways that negatively impact one's relationships and quality of life. It often involves putting one's own needs at a lower priority than others while being excessively preoccupied with the needs of others. 7. Cognitive Distortions / all-of-nothing thinking (Splitting) – Thinking of things in absolute terms, like "always", "every", "never", and "there is no alternative". 8. Cognitive Distortions / Mental Filter – Focusing almost exclusively on certain, usually negative or upsetting, aspects of an event while ignoring other positive aspects. 9. Cognitive Distortions / Disqualifying the Positive – Continually reemphasizing or "shooting down" positive experiences for arbitrary reasons. 10. Cognitive Disorder / Labeling and Mislabeling – Explaining behaviors or events, merely by naming them in an over-generalized manner. -

Transposition, 6 | 2016 Copying Machines 2

Transposition Musique et Sciences Sociales 6 | 2016 Lignes d’écoute, écoute en ligne Copying machines Unconscious musical plagiarism and the mediatisation of listening and memory John Shiga Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/transposition/1569 DOI: 10.4000/transposition.1569 ISSN: 2110-6134 Publisher CRAL - Centre de recherche sur les arts et le langage Electronic reference John Shiga, « Copying machines », Transposition [Online], 6 | 2016, Online since 20 March 2017, connection on 30 July 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/transposition/1569 ; DOI : 10.4000/ transposition.1569 This text was automatically generated on 30 July 2019. La revue Transposition est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Partage dans les Mêmes Conditions 4.0 International. Copying machines 1 Copying machines Unconscious musical plagiarism and the mediatisation of listening and memory John Shiga 1 Introduced into musical copyright discourse in the early twentieth century, the notion of cryptomnesia or unconscious plagiarism highlights a key tension in copyright law. On the one hand, copyright acts as a recognizing authority for claims to authorship and originality, thus providing economic incentives to authors whose work is “original,” which in turn encourages cultural innovation. On the other hand, copyright facilitates ownership and control of cultural works by institutions rather than by authors, since its minimal notion of “originality” and extended period of protection encourage the production -

The Digital Expansion of the Mind: Implications of Internet Usage For

Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 8 (2019) 1–14 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition journa l homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jarmac The Digital Expansion of the Mind: Implications of Internet Usage for Memory and Cognition a,∗ b Elizabeth J. Marsh , Suparna Rajaram a Duke University, United States b Stony Brook University, United States The internet is rapidly changing what information is available as well as how we find it and share it with others. Here we examine how this “digital expansion of the mind” changes cognition. We begin by identifying ten properties of the internet that likely affect cognition, roughly organized around internet content (e.g., the sheer amount of information available), internet usage (e.g., the requirement to search for information), and the people and communities who create and propagate content (e.g., people are connected in an unprecedented fashion). We use these properties to explain (or ask questions about) internet-related phenomena, such as habitual reliance on the internet, the propagation of misinformation, and consequences for autobiographical memory, among others. Our goal is to consider the impact of internet usage on many aspects of cognition, as people increasingly rely on the internet to seek, post, and share information. Keywords: Memory, Cognition, Internet, External memory, Metacognition, Social memory General Audience Summary The internet is rapidly changing what information is available to us as well as how we find that information and share it with others. Here we ask how this “digital expansion of the mind” may change cognition. -

The Three Amnesias

The Three Amnesias Russell M. Bauer, Ph.D. Department of Clinical and Health Psychology College of Public Health and Health Professions Evelyn F. and William L. McKnight Brain Institute University of Florida PO Box 100165 HSC Gainesville, FL 32610-0165 USA Bauer, R.M. (in press). The Three Amnesias. In J. Morgan and J.E. Ricker (Eds.), Textbook of Clinical Neuropsychology. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis/Psychology Press. The Three Amnesias - 2 During the past five decades, our understanding of memory and its disorders has increased dramatically. In 1950, very little was known about the localization of brain lesions causing amnesia. Despite a few clues in earlier literature, it came as a complete surprise in the early 1950’s that bilateral medial temporal resection caused amnesia. The importance of the thalamus in memory was hardly suspected until the 1970’s and the basal forebrain was an area virtually unknown to clinicians before the 1980’s. An animal model of the amnesic syndrome was not developed until the 1970’s. The famous case of Henry M. (H.M.), published by Scoville and Milner (1957), marked the beginning of what has been called the “golden age of memory”. Since that time, experimental analyses of amnesic patients, coupled with meticulous clinical description, pathological analysis, and, more recently, structural and functional imaging, has led to a clearer understanding of the nature and characteristics of the human amnesic syndrome. The amnesic syndrome does not affect all kinds of memory, and, conversely, memory disordered patients without full-blown amnesia (e.g., patients with frontal lesions) may have impairment in those cognitive processes that normally support remembering. -

Cognitive Disorders: a Perspective from the Neurology Clinic

This is a repository copy of Functional (Psychogenic) Cognitive Disorders: A Perspective from the Neurology Clinic. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/93827/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Stone, J., Pal, S., Blackburn, D. et al. (3 more authors) (2015) Functional (Psychogenic) Cognitive Disorders: A Perspective from the Neurology Clinic. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 49 (s1). S5-S17. ISSN 1387-2877 https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-150430 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Functional (psychogenic) memory disorders - a perspective from the neurology clinic Jon Stone1 , Suvankar Pal1,2, Daniel Blackburn2, Markus Reuber2, Parvez Thekkumpurath1, Alan Carson1,3 1Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Western General Hospital, Crewe Rd, Edinburgh EH4 2XU, UK.