Aging and the Seven Sins of Memory Benton H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compare and Contrast Two Models Or Theories of One Cognitive Process with Reference to Research Studies

! The following sample is for the learning objective: Compare and contrast two models or theories of one cognitive process with reference to research studies. What is the question asking for? * A clear outline of two models of one cognitive process. The cognitive process may be memory, perception, decision-making, language or thinking. * Research is used to support the models as described. The research does not need to be outlined in a lot of detail, but underatanding of the role of research in supporting the models should be apparent.. * Both similarities and differences of the two models should be clearly outlined. Sample response The theory of memory is studied scientifically and several models have been developed to help The cognitive process describe and potentially explain how memory works. Two models that attempt to describe how (memory) and two models are memory works are the Multi-Store Model of Memory, developed by Atkinson & Shiffrin (1968), clearly identified. and the Working Memory Model of Memory, developed by Baddeley & Hitch (1974). The Multi-store model model explains that all memory is taken in through our senses; this is called sensory input. This information is enters our sensory memory, where if it is attended to, it will pass to short-term memory. If not attention is paid to it, it is displaced. Short-term memory Research. is limited in duration and capacity. According to Miller, STM can hold only 7 plus or minus 2 pieces of information. Short-term memory memory lasts for six to twelve seconds. When information in the short-term memory is rehearsed, it enters the long-term memory store in a process called “encoding.” When we recall information, it is retrieved from LTM and moved A satisfactory description of back into STM. -

Episodic Memory in Transient Global Amnesia: Encoding, Storage, Or Retrieval Deficit?

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.148 on 1 February 1999. Downloaded from 148 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999;66:148–154 Episodic memory in transient global amnesia: encoding, storage, or retrieval deficit? Francis Eustache, Béatrice Desgranges, Peggy Laville, Bérengère Guillery, Catherine Lalevée, Stéphane SchaeVer, Vincent de la Sayette, Serge Iglesias, Jean-Claude Baron, Fausto Viader Abstract evertheless this division into processing stages Objectives—To assess episodic memory continues to be useful in helping understand (especially anterograde amnesia) during the working of memory systems”. These three the acute phase of transient global amne- stages may be defined in the following way: (1) sia to diVerentiate an encoding, a storage, encoding, during which perceptive information or a retrieval deficit. is transformed into more or less stable mental Methods—In three patients, whose am- representations; (2) storage (or consolidation), nestic episode fulfilled all current criteria during which mnemonic information is associ- for transient global amnesia, a neuro- ated with other representations and maintained psychological protocol was administered in long term memory; (3) retrieval, during which included a word learning task which the subject can momentarily reactivate derived from the Grober and Buschke’s mnemonic representations. These definitions procedure. will be used in the present study. Results—In one patient, the results sug- Regarding the retrograde amnesia of TGA, it gested an encoding deficit, -

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory John Dunlosky and Robert A. Bjork Introduction Memory has been of interest to scholars and laypeople alike for over 2,000 years. In a rather gruesome example from antiquity, Cicero tells the story of Simonides (557– 468 BC), who discovered the method of loci, which is a powerful mental mnemonic for enhancing one’s memory. Simonides was at a banquet of a nobleman, Scopas. To honor him, Simonides sang a poem, but to Scopas’s chagrin, the poem also honored two young men, Castor and Pollux. Being upset, Scopas told Simonides that he was to receive only half his wage. Simonides was later called from the banquet, and legend has it that the banquet room collapsed, and all those inside were crushed. To help bereaved families identify the victims, Simonides reportedly was able to name every- one according to the place where they sat at the table, which gave him the idea that order brings strength to our memories and that to employ this ability people “should choose localities, then form mental images of things they wanted to store in their memory, and place these in the localities” (Cicero, 2001). Tis example highlights an early discovery that has had important applied impli- cations for improving the functioning of memory (see, e.g., Yates, 1997). Memory theory was soon to follow. Aristotle (385–322 BC) claimed that memory arises from three processes: Events are associated (1) through their relative similarity or (2) rela- tive dissimilarity and (3) when they co-occur together in space and time. -

Sleep, Memory, and Aging: Effects of Pre- and Post- Sleep Delays and Interference on Memory in Younger and Older Adults Michael Scullin Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 1-1-2011 Sleep, Memory, and Aging: Effects of Pre- and Post- Sleep Delays and Interference on Memory in Younger and Older Adults Michael Scullin Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Scullin, Michael, "Sleep, Memory, and Aging: Effects of Pre- and Post-Sleep Delays and Interference on Memory in Younger and Older Adults" (2011). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 640. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/640 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Psychology Dissertation Examination Committee: Mark McDaniel, Chair Sandy Hale Larry Jacoby Henry Roediger, III Paul Shaw James Wertsch Sleep, Memory, and Aging: Effects of Pre- and Post-Sleep Delays and Interference on Memory in Younger and Older Adults by Michael K. Scullin A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2011 Saint Louis, Missouri Abstract The present research investigated the relationship between sleep and memory in younger and older adults. Previous research has demonstrated that during the deep sleep stage (i.e., slow wave sleep), recently learned memories are reactivated and consolidated in younger adults. -

Mnemonics in a Mnutshell: 32 Aids to Psychiatric Diagnosis

Mnemonics in a mnutshell: 32 aids to psychiatric diagnosis Clever, irreverent, or amusing, a mnemonic you remember is a lifelong learning tool ® Dowden Health Media rom SIG: E CAPS to CAGE and WWHHHHIMPS, mnemonics help practitioners and trainees recall Fimportant lists (suchCopyright as criteriaFor for depression,personal use only screening questions for alcoholism, or life-threatening causes of delirium, respectively). Mnemonics’ effi cacy rests on the principle that grouped information is easi- er to remember than individual points of data. Not everyone loves mnemonics, but recollecting diagnostic criteria is useful in clinical practice and research, on board examinations, and for insurance reimbursement. Thus, tools that assist in recalling di- agnostic criteria have a role in psychiatric practice and IMAGES teaching. JUPITER In this article, we present 32 mnemonics to help cli- © nicians diagnose: • affective disorders (Box 1, page 28)1,2 Jason P. Caplan, MD Assistant clinical professor of psychiatry • anxiety disorders (Box 2, page 29)3-6 Creighton University School of Medicine 7,8 • medication adverse effects (Box 3, page 29) Omaha, NE • personality disorders (Box 4, page 30)9-11 Chief of psychiatry • addiction disorders (Box 5, page 32)12,13 St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center Phoenix, AZ • causes of delirium (Box 6, page 32).14 We also discuss how mnemonics improve one’s Theodore A. Stern, MD Professor of psychiatry memory, based on the principles of learning theory. Harvard Medical School Chief, psychiatric consultation service Massachusetts General Hospital How mnemonics work Boston, MA A mnemonic—from the Greek word “mnemonikos” (“of memory”)—links new data with previously learned information. -

Post-Encoding Stress Does Not Enhance Memory Consolidation: the Role of Cortisol and Testosterone Reactivity

brain sciences Article Post-Encoding Stress Does Not Enhance Memory Consolidation: The Role of Cortisol and Testosterone Reactivity Vanesa Hidalgo 1,* , Carolina Villada 2 and Alicia Salvador 3 1 Department of Psychology and Sociology, Area of Psychobiology, University of Zaragoza, 44003 Teruel, Spain 2 Department of Psychology, Division of Health Sciences, University of Guanajuato, Leon 37670, Mexico; [email protected] 3 Department of Psychobiology and IDOCAL, University of Valencia, 46010 Valencia, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-978-645-346 Received: 11 October 2020; Accepted: 15 December 2020; Published: 16 December 2020 Abstract: In contrast to the large body of research on the effects of stress-induced cortisol on memory consolidation in young people, far less attention has been devoted to understanding the effects of stress-induced testosterone on this memory phase. This study examined the psychobiological (i.e., anxiety, cortisol, and testosterone) response to the Maastricht Acute Stress Test and its impact on free recall and recognition for emotional and neutral material. Thirty-seven healthy young men and women were exposed to a stress (MAST) or control task post-encoding, and 24 h later, they had to recall the material previously learned. Results indicated that the MAST increased anxiety and cortisol levels, but it did not significantly change the testosterone levels. Post-encoding MAST did not affect memory consolidation for emotional and neutral pictures. Interestingly, however, cortisol reactivity was negatively related to free recall for negative low-arousal pictures, whereas testosterone reactivity was positively related to free recall for negative-high arousal and total pictures. -

Memory Specificity, but Not Perceptual Load, Affects Susceptibility to Misleading Information

Memory specificity, but not perceptual load, affects susceptibility to misleading information Francesca R. Farina1,2,* & Ciara M. Greene1 1School of Psychology, University College Dublin, Ireland. 2Trinity College Institute of Neuroscience, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. Note: This paper has not yet been peer-reviewed. Please contact the authors before citing. Correspondence may be sent to Francesca Farina, Trinity College Institute of Neuroscience, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. Email: [email protected] 1 Abstract The purpose of this study was to examine the role of perceptual load in eyewitness memory accuracy and susceptibility to misinformation at immediate and delayed recall. Despite its relevance to real-world situations, previous research in this area is limited. A secondary aim was to establish whether trait-based memory specificity can protect against susceptibility to misinformation. Participants (n=264) viewed a 1-minute video depicting a crime and completed a memory questionnaire immediately afterwards and one week later. Memory specificity was measured via an online version of the Autobiographical Memory Test (AMT). We found a strong misinformation effect, but no effect of perceptual load on memory accuracy or suggestibility at either timepoint. Memory specificity was a significant predictor of accuracy for both neutrally phrased and leading questions, though the effect was weaker after a one-week delay. Results suggest that specific autobiographical memory, but not perceptual load, enhances eyewitness memory and protects against misinformation. Keywords Perceptual load; memory specificity; eyewitness; misinformation. 2 General Audience Summary The misinformation effect is a memory impairment for a past event that occurs when a person is presented with leading information. Leading information can distort the original details of a memory and produce false memories. -

2 Weeks to a Younger Brain Book Publishing

2 WEEKS TO A YOUNGER BRAIN 2 WEEKS TO A YOUNGER BRAIN GARY SMALL, MD AND GIGI VORGAN www.humanixbooks.com Boca Raton, FL, USA Two Weeks to a Younger Brain © 2015 Humanix Books All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any other infor- mation storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Interior: Ben Davis Index: Yvette M. Chin For information, contact: Humanix Books P.O. Box 20989 West Palm Beach, FL 33416 USA www.humanixbooks.com email: [email protected] Humanix Books is a division of Humanix Publishing, LLC. Its trademark, consisting of the words “Humanix Books” is registered with the US Patent and Trademark Of- fice, and in other countries. Disclaimer: The information presented in this book is meant to be used for general resource purposes only; it is not intended as specific medical advice for any individ- ual and should not substitute medical advice from a healthcare professional. If you have (or think you may have) a medical problem, speak to your doctor or a healthcare practitioner immediately about your risk and possible treatments. Do not engage in any therapy or treatment without consulting a medical professional. Printed in the United States of America and the United Kingdom. ISBN (Hardcover) 978-1-63006-030-5 ISBN (E-book) 978-1-63006-031-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2014958068 Acknowledgments E ARE GRATEFUL TO the many volunteers and patients who Wparticipated in the research studies that inspired this book. -

Memory & Cognition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Syracuse University Research Facility and Collaborative Environment Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects Projects Spring 5-1-2006 Memory & Cognition: What difference does gender make? Donna J. Bridge Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone Part of the Cognition and Perception Commons, Cognitive Psychology Commons, and the Other Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Bridge, Donna J., "Memory & Cognition: What difference does gender make?" (2006). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 655. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/655 This Honors Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Memory & Cognition: What difference does gender make? Donna J. Bridge Department of Psychology Syracuse University Abstract Small but significant gender differences, typically favoring women, have pre- viously been observed in experiments measuring human episodic memory performance. In three studies measuring episodic memory, we compared performance levels for men and women. Secondary analysis from a paired- associate learning task revealed a superior ability for women to learn single function pairs (i.e. words that are represented in only one pair), but per- formance levels for double function pairs (i.e. pairs that contain words that are also used in one other pair) were similar for men and women. -

Reversible Verbal and Visual Memory Deficits After Left Retrosplenial Infarction

Journal of Clinical Neurology / Volume 3 / March, 2007 Case Report Reversible Verbal and Visual Memory Deficits after Left Retrosplenial Infarction Jong Hun Kim, M.D.*, Kwang-Yeol Park, M.D.†, Sang Won Seo, M.D.*, Duk L. Na, M.D.*, Chin-Sang Chung, M.D.*, Kwang Ho Lee, M.D.*, Gyeong-Moon Kim, M.D.* *Department of Neurology, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea †Department of Neurology, Chung-Ang University Medical Center, Chung-Ang University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea The retrosplenial cortex is a cytoarchitecturally distinct brain structure located in the posterior cingulate gyrus and bordering the splenium, precuneus, and calcarine fissure. Functional imaging suggests that the retrosplenium is involved in memory, visuospatial processing, proprioception, and emotion. We report on a patient who developed reversible verbal and visual memory deficits following a stroke. Neuro- psychological testing revealed both anterograde and retrograde memory deficits in verbal and visual modalities. Brain diffusion-weighted and T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated an acute infarction of the left retrosplenium. J Clin Neurol 3(1):62-66, 2007 Key Words : Retrosplenium, Memory, Amnesia We report on a patient who developed both verbal INTRODUCTION and visual memory deficits after an acute infarction of the retrosplenial cortex. The main structures related to human memory are the Papez circuit, the basolateral limbic circuit, and the basal forebrain, which communicate with each other through white-matter tracts. Damage to these structures (in- cluding the communication tracts) from hemorrhages, infarctions, and tumors can result in memory dis- turbances.1,2 In addition to these structures, Valenstein et al. -

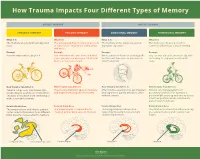

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Investigating the Roles of Memory and Metamemory in Trauma-Related Outcomes

ABSTRACT A PTSD ANALOGUE STUDY: INVESTIGATING THE ROLES OF MEMORY AND METAMEMORY IN TRAUMA-RELATED OUTCOMES Ban Hong (Phylice) Lim, Ph.D. Department of Psychology Northern Illinois University, 2016 Michelle M. Lilly, Director Trauma survivors who develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often display symptoms of memory fragmentation such as an impaired ability to recall trauma memories. These observations are consistent with prominent theories of PTSD, which consider memory fragmentation as a central feature of PTSD. Correspondingly, most empirically supported interventions for PTSD focus on addressing dysfunctional thoughts and behaviors and integrating fragmented memories of the event. More recently, this assumption has been challenged by research indicating that metamemory – one’s subjective beliefs about one’s memory functioning and quality – may partially account for reported memory fragmentation among individuals with PTSD. Memory underconfidence, regardless of whether or not it is founded or wholly accurate, may lead to feelings of anxiety, especially in the process of recalling and making sense of one’s trauma memory. Despite the intertwined nature of their relationship, the association between memory and metamemory has been understudied in the trauma literature. This dissertation investigated whether PTSD is a disorder of memory fragmentation, perceived memory fragmentation, or both by examining the association between memory and metamemory. A trauma analogue between-subjects experimental design was employed. Eighty- four healthy participants were randomly assigned to receive either positive feedback or negative feedback after completing a standardized memory assessment. Despite the use of randomization, the manipulation groups systematically differed on both baseline memory ability and baseline memory confidence. Contrary to the first hypothesis, after controlling for the effect of baseline metamemory beliefs, the groups did not differ on their recall task performance, F(1,80) = .34, p = .56.