“Unavoidable”? - Tacit Rationality and the Reinforcement of Informal Institutions in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xi Jinping's War on Corruption

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2015 The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption Harriet E. Fisher University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Harriet E., "The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption" (2015). Honors Theses. 375. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/375 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping’s War on Corruption By Harriet E. Fisher A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies at the Croft Institute for International Studies and the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi May 2015 Approved by: ______________________________ Advisor: Dr. Gang Guo ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Kees Gispen ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Peter K. Frost i © 2015 Harriet E. Fisher ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii For Mom and Pop, who taught me to learn, and Helen, who taught me to teach. iii Acknowledgements I am indebted to a great many people for the completion of this thesis. First, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Gang Guo, for all his guidance during the thesis- writing process. His expertise in China and its endemic political corruption were invaluable, and without him, I would not have had a topic, much less been able to complete a thesis. -

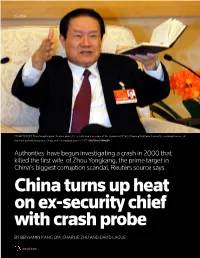

China Turns up Heat on Ex-Security Chief with Crash Probe

CHINA PRIME TARGET: Zhou Yongkang was head of domestic security and a member of the Communist Party Standing Politburo Committee, making him one of the most powerful people in China, until he stepped down in 2012. REUTERS/STRINGER Authorities have begun investigating a crash in 2000 that killed the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, the prime target in China’s biggest corruption scandal, Reuters source says. China turns up heat on ex-security chief with crash probe BY BENJAMIN KANG LIM, CHARLIE ZHU AND DAVID LAGUE SPECIAL REPORT 1 CHINA’S POWER STRUGGLE BEIJING/HONG KONG, SEPTEMBER 12, 2014 ittle is known about the exact circum- stances in which Wang Shuhua was Lkilled. What has been reported, in the Chinese media, is that she died in a road ac- cident sometime in 2000, shortly after she was divorced from her husband. And that at least one vehicle with a military license plate may have been involved in the crash. Fourteen years later, investigators are looking into her death. Their sudden inter- est has nothing to do with Wang herself. It has to do with the identity of her ex-hus- band – once one of China’s most powerful men and now the prime target in President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign. Investigators are probing the death of the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, China’s HUNTING TIGERS: President Xi Jinping has launched the biggest corruption crackdown since the retired security czar, a source with di- communists came to power in 1949, going after “tigers” or high-ranking officials as well as “flies”. -

Operational Guidance Note

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE NOTE CHINA OGN v.12 Issued October 2013 – updated 6 December 2014 OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE NOTE CHINA CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1.1 – 1.4 2. Country assessment 2.1 Actors of protection 2.2 Internal relocation 2.3 Country guidance caselaw 2.4 3. Main categories of claims 3.1 – 3.8 Falun Gong/Falun Dafa 3.9 Involvement with pro-Tibetan/pro/independence political organisations 3.10 Involvement with illegal religious organisations 3.11 Involvement with illegal political organisations or perceived political 3.12 opposition Forced abortion/sterilisation under ‘one child policy’ 3.13 Double Jeopardy 3.14 Civil protests and petitioners 3.15 Prison Conditions 3.16 4. Minors claiming in their own right 4.1 – 4.3 5. Medical Treatment 5.1 – 5.5 6. Returns 6.1 – 6.5 Decision makers assessing claims based on Christianity should refer to the Country Information and Guidance on: ► China: Christians, 13 June 2014 1. Introduction 1.1 This document provides Home Office caseworkers with guidance on the nature and handling of the most common types of claims received from nationals/residents of China, including whether claims are or are not likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or Discretionary Leave. Caseworkers must refer to the relevant Asylum Instructions for further details of the policy on these areas. 1.2 Caseworkers must not base decisions on the country of origin information in this guidance; it is included to provide context only and does not purport to be comprehensive. The conclusions in this guidance are based on the totality of the available evidence, not just the brief extracts contained herein, and caseworkers must likewise take into account all available evidence. -

Research on the Impact of Land Circulation on the Income Gap of Rural Households: Evidence from CHIP

land Article Research on the Impact of Land Circulation on the Income Gap of Rural Households: Evidence from CHIP Congjia Huo 1 and Lingming Chen 1,2,* 1 Department of Economics, School of Business, Hunan University of Science and Technology (HNUST), Xiantang 411201, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Economics & Statistics, School of Economics and Management, Xinyu University (XYU), Xinyu 338004, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-158-7009-2285 Abstract: With the continued development of the economy, the income gap among Chinese rural households continues to widen. The land system plays a decisive role in developing “agriculture, rural areas and farmers” and land circulation is a factor in the increase in income inequality among farm households. Based on the 2013 China Household Income Project (CHIP), this article used the re-centered influence function (RIF) regression method to empirically test the impact of rural land circulation on the income gap of rural households in China in three regions: the central, eastern and western regions. The quantile regression tested the impact mechanism of income inequality of rural households from the perspective of labor mobility and land circulation. The empirical results showed that land circulation increases the income inequality of rural households. The theoretical mechanism test proved that the dynamic relationship between land circulation and labor mobility increases rural household income. However, this increase has a greater effect on rural households with a high Citation: Huo, C.; Chen, L. Research income and a small effect on rural households with a low income, resulting in a further widening of on the Impact of Land Circulation on the income gap. -

Chinese Politics in the Xi Jingping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership

CHAPTER 1 Governance Collective Leadership Revisited Th ings don’t have to be or look identical in order to be balanced or equal. ڄ Maya Lin — his book examines how the structure and dynamics of the leadership of Tthe Chinese Communist Party (CCP) have evolved in response to the chal- lenges the party has confronted since the late 1990s. Th is study pays special attention to the issue of leadership se lection and composition, which is a per- petual concern in Chinese politics. Using both quantitative and qualitative analyses, this volume assesses the changing nature of elite recruitment, the generational attributes of the leadership, the checks and balances between competing po liti cal co ali tions or factions, the behavioral patterns and insti- tutional constraints of heavyweight politicians in the collective leadership, and the interplay between elite politics and broad changes in Chinese society. Th is study also links new trends in elite politics to emerging currents within the Chinese intellectual discourse on the tension between strongman politics and collective leadership and its implications for po liti cal reforms. A systematic analy sis of these developments— and some seeming contradictions— will help shed valuable light on how the world’s most populous country will be governed in the remaining years of the Xi Jinping era and beyond. Th is study argues that the survival of the CCP regime in the wake of major po liti cal crises such as the Bo Xilai episode and rampant offi cial cor- ruption is not due to “authoritarian resilience”— the capacity of the Chinese communist system to resist po liti cal and institutional changes—as some foreign China analysts have theorized. -

Chapter 3 China: Xi Jinping's Administration— Proactive Policies

Chapter 3 China: Xi Jinping’s Administration— Proactive Policies at Home and Abroad or China, 2014 was a year when initiatives of the Xi Jinping administration Fcame to the forefront. In domestic politics, it was a year of important changes, as the anti-corruption campaign continued to make itself felt, resulting, for example, in Zhou Yongkang, a former member of the Politburo Standing Committee, and Xu Caihou, former vice chairman of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Military Commission (CMC), being expelled from the party. Xi Jinping, who was already president as well as general secretary of the party, took the position of chairman of the new National Security Commission and created a number of small leading groups, part of his efforts to strengthen his structural authority. Meanwhile elements of instability grew as well, such as the number of bombings that took place in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, and the CPC is cracking down vigorously. President Xi has assertively engaged in foreign policy, leading at times to strong unilateral positions such as China’s location of oil drilling equipment in the South China Sea. China is seeking to form “a new type of major-power relations” with the United States, but China’s actions in the South China Sea and the confrontation over cyber spying make it unclear whether China will be able to achieve the kind of US-China relations it desires. President Xi is also engaging in periphery diplomacy, seeking to ensure China’s peaceful development by reinforcing its economic relations with its neighbors and calling for an Asian New Security Concept, while strengthening its criticism of the system of alliances centered on the United States. -

The Realistic Representation, Inducing Factors and Governance Strategy of Family Corruption Qiwen Tang1, *

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 451 Proceedings of the 2020 5th International Conference on Humanities Science and Society Development (ICHSSD 2020) The Realistic Representation, Inducing Factors and Governance Strategy of Family Corruption Qiwen Tang1, * 1Department of Law and Politics, North China Electric Power University. Baoding, Hebei 071000,China *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Since the 18th national congress of the communist party of China (CPC), the CPC central committee with Xi Jinping at the core of leadership has launched an anti-graft campaign with an all-inclusive and zero-tolerance attitude. Among all the corrupt behaviors, "family corruption" has undoubtedly become a typical corrupt behavior, which has bad social influence, diverse forms and distinctive characteristics. Family corruption can be divided into three modes according to the characteristics of corruption behavior, namely, common bribery mode, power shadow mode and option investment mode. The factors leading to family corruption are various. We can make a systematic analysis from four aspects: organizational system, social supervision, officials and family ethics. Through the analysis of the factors that induce family corruption, we can actually determine the corresponding governance strategies: improve the system, strengthen supervision, update the concept, and cultivate political ethics. Keywords: family corruption; realistic representation; inducing factors; governance strategy 1. INTRODUCTION 2. THE REALISTIC REPRESENTATION OF FAMILY CORRUPTION Since the 18th national congress of the communist party of China (CPC), the fight against corruption has achieved remarkable results. With the anti-corruption storm advancing, Zhou Yongkang, Ling Jihua, Su Rong, and 2.1. The behavior pattern of family corruption other groups of "big tigers" fall, and family corruption The so-called family corruption refers to the behavior that cases are increasingly surfaced. -

Zhou-Master.Pdf (1.441Mb)

Are You a Good Chinese Musician? The Ritual Transmission of Social Norms in a Chinese Reality Music Talent Show Miaowen Zhou Master’s Thesis in East Asian Culture and History (EAST4591 - 60 Credits) Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2015 © Miaowen Zhou 2015 Are You a Good Chinese Musician? The Ritual Transmission of Social Norms of a Chinese Reality Music Talent Show http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo II Abstract The sensational success of a Chinese reality music talent show, Super Girls’ Voice (SGV), in 2005 not only crowned many unknown Chinese girls/women with the hail of celebrity overnight, but also caused hot debates on many subjects including whether the show triggered cultural, even political democracy in China. 10 years have passed and China is in another heyday of reality music talent shows. However, the picture differs from before. For instance, not everybody can take part in it anymore. And the state television China Central Television (CCTV) joined the competition for market share. It actually became a competitive player of “reality” by claiming to find the best original and creative Chinese musicians whose voices CCTV previously avoided or oppressed. In this thesis, I will examine one CCTV show, The Song of China (SOC), in order to examine what the norms of good Chinese music and musicians are in the context of reality music talent shows. My work will hopefully give you some insights into the characteristics and the wider social and political influences of such reality music talent shows in the post-SGV era. -

Detentions Cast Pall Over Macau's Recovery P7

FLYING EYE HOSPITAL IN RUSSIA SYRIA HALT VIETNAM , MACAU ALEPPO AIRSTRIKES The unique aircraft arrived BRACES Russian and Syrian warplanes in Macau following its sight- FOR halted their airstrikes on Aleppo. saving mission in Shenyang, TYPHOON Moscow described the move as China SARIKA an “humanitarian pause” P2 P12 P14 SYRIA WED.19 Oct 2016 T. 24º/ 28º C H. 80/ 98% facebook.com/mdtimes + 11,000 MOP 7.50 2666 N.º HKD 9.50 FOUNDER & PUBLISHER Kowie Geldenhuys EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Paulo Coutinho www.macaudailytimes.com.mo “ THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGIN’ ” WORLD BRIEFS GAMING AP PHOTO Detentions cast pall CHINA-PHILIPPINES This week’s visit to China by Philippine President P7 Rodrigo Duterte points toward a restoration of over Macau’s recovery trust between the sides following recent tensions over their South China Sea territorial dispute, Chinese official news agency says. More on p11 RENATO MARQUES RENATO CHINA Entertainment giant Wanda is offering producers a rebate of 40 percent to promote its upcoming USD8b movie studio in eastern China in an ambitious bid to establish the complex as a major production base in Asia. More on p10 AP PHOTO THAILAND People waited patiently in long queues outside government banks to secure special commemorative 100 baht currency notes in honor of the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej. BANGLADESH Three Bangladeshi men have been identified as the financiers of the July 1 attack in which a group of assailants tortured and killed 20 hostages at a restaurant in Dhaka, a counterterrorism official says. AP PHOTO NEW ZEALAND A U.S. -

Urban Demolition and the Aesthetics of Recent Ruins In

Urban Demolition and the Aesthetics of Recent Ruins in Experimental Photography from China Xavier Ortells-Nicolau Directors de tesi: Dr. Carles Prado-Fonts i Dr. Joaquín Beltrán Antolín Doctorat en Traducció i Estudis Interculturals Departament de Traducció, Interpretació i d’Estudis de l’Àsia Oriental Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2015 ii 工地不知道从哪天起,我们居住的城市 变成了一片名副其实的大工地 这变形记的场京仿佛一场 反复上演的噩梦,时时光顾失眠着 走到睡乡之前的一刻 就好像门面上悬着一快褪色的招牌 “欢迎光临”,太熟识了 以到于她也真的适应了这种的生活 No sé desde cuándo, la ciudad donde vivimos 比起那些在工地中忙碌的人群 se convirtió en un enorme sitio de obras, digno de ese 她就像一只蜂后,在一间屋子里 nombre, 孵化不知道是什么的后代 este paisaJe metamorfoseado se asemeja a una 哦,写作,生育,繁衍,结果,死去 pesadilla presentada una y otra vez, visitando a menudo el insomnio 但是工地还在运转着,这浩大的工程 de un momento antes de llegar hasta el país del sueño, 简直没有停止的一天,今人绝望 como el descolorido letrero que cuelga en la fachada de 她不得不设想,这能是新一轮 una tienda, 通天塔建造工程:设计师躲在 “honrados por su preferencia”, demasiado familiar, 安全的地下室里,就像卡夫卡的鼹鼠, de modo que para ella también resulta cómodo este modo 或锡安城的心脏,谁在乎呢? de vida, 多少人满怀信心,一致于信心成了目标 en contraste con la multitud aJetreada que se afana en la 工程质量,完成日期倒成了次要的 obra, 我们这个时代,也许只有偶然性突发性 ella parece una abeja reina, en su cuarto propio, incubando quién sabe qué descendencia. 能够结束一切,不会是“哗”的一声。 Ah, escribir, procrear, multipicarse, dar fruto, morir, pero el sitio de obras sigue operando, este vasto proyecto 周瓒 parece casi no tener fecha de entrega, desesperante, ella debe imaginar, esto es un nuevo proyecto, construir una torre de Babel: los ingenieros escondidos en el sótano de seguridad, como el topo de Kafka o el corazón de Sión, a quién le importa cuánta gente se llenó de confianza, de modo que esa confianza se volvió el fin, la calidad y la fecha de entrega, cosas de importancia secundaria. -

P12 Layout 1

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 19, 2016 INTERNATIONAL Tears and tortoises - Chinese TV unveils graft secrets BEIJING: With a tale of a dead pet tortoise given Three of those “tigers” get camera time in the Zhou “set his expectations upon protection Describing his failings, Sichuan’s Li, given a 13- Buddhist rites and a senior official shedding tears first episode Bai Enpei, the former party boss of from supernatural beings and was widely involved year jail term last year, struggled and failed to for his crimes, state television has begun airing a southwestern Yunnan province; Zhou Benshun, an in superstitious practices”, the narrator says. “After keep back tears. “From a young age I hoped that documentary that takes viewers behind the scenes ex-party chief of northern Hebei province and Li a tortoise died at his home, he specially had scrip- under the leadership of the party ... I could get of some of China’s most dramatic corruption cases. Chuncheng, a former deputy party boss of south- tures transcribed and buried with it.” Zhou even progress for society, make the people happy,” Li The eight-part series that kicked off late on western Sichuan. Bai and Li have both been con- had a nanny for his pets, investigator Wang Han said. “In the end, because of myself, I didn’t get Monday promises an unusual warts-and-all victed, while Zhou awaits trial. The juiciest details told the program. The three disgraced officials all there. I really let the party down. I let the people approach to revealing the story behind the dirty come from the probe into Zhou. -

Journal of Contemporary China

JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY CHINA Article Index By Subject Matter Vol. 6, No. 14, January 1997 – Vol. 30, No. 129, May 2021 Table of Contents Art and Literature • Financial Crisis • Chinese Art, Music, Literature, • Financial institutions Television, and Cinema • Financial markets Culture • Monetary policy • Culture / Traditional Culture • Fiscal policy Developmental Studies Foreign Relations • Development • China-Africa Relations • China-Australia Relations Economics • China-East Asia Relations • Agriculture • China-EU, Europe Relations • Business • China-General Foreign Relations • Economy/ Chinese Economy • China – India Relations • Economic and Financial Reform • China – Japan Relations • Entrepreneurs • China - Middle East / Central Asia • Enterprise Relations • Foreign Trade • China – North and South American • Real Estate / Construction Relations Rights (Property, Intellectual • • China - North and South Korea Property) Relations Rising China • • China – Pakistan Relations State-Owned Enterprises • • China – Periphery Relations • Taxes • China – Russia Relations Education • China – South East Asia Relations • College / University • China – United States Relations • Education • Cross-Boundary Rivers Government Energy • Central-Local Government Relations • Governance Environment • Climate Change • Local Elections • Environment / Pollution • Local Governments • Natural Resources • National People’s Congress (NPC) • Provincial Governments/ Financial System Intergovernmental Relations • Finance • Risk Management • Rule of Law Internationalization