Politics of Anticorruption in China: Paradigm Change of the Party's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research on the Impact of Land Circulation on the Income Gap of Rural Households: Evidence from CHIP

land Article Research on the Impact of Land Circulation on the Income Gap of Rural Households: Evidence from CHIP Congjia Huo 1 and Lingming Chen 1,2,* 1 Department of Economics, School of Business, Hunan University of Science and Technology (HNUST), Xiantang 411201, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Economics & Statistics, School of Economics and Management, Xinyu University (XYU), Xinyu 338004, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-158-7009-2285 Abstract: With the continued development of the economy, the income gap among Chinese rural households continues to widen. The land system plays a decisive role in developing “agriculture, rural areas and farmers” and land circulation is a factor in the increase in income inequality among farm households. Based on the 2013 China Household Income Project (CHIP), this article used the re-centered influence function (RIF) regression method to empirically test the impact of rural land circulation on the income gap of rural households in China in three regions: the central, eastern and western regions. The quantile regression tested the impact mechanism of income inequality of rural households from the perspective of labor mobility and land circulation. The empirical results showed that land circulation increases the income inequality of rural households. The theoretical mechanism test proved that the dynamic relationship between land circulation and labor mobility increases rural household income. However, this increase has a greater effect on rural households with a high Citation: Huo, C.; Chen, L. Research income and a small effect on rural households with a low income, resulting in a further widening of on the Impact of Land Circulation on the income gap. -

The Realistic Representation, Inducing Factors and Governance Strategy of Family Corruption Qiwen Tang1, *

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 451 Proceedings of the 2020 5th International Conference on Humanities Science and Society Development (ICHSSD 2020) The Realistic Representation, Inducing Factors and Governance Strategy of Family Corruption Qiwen Tang1, * 1Department of Law and Politics, North China Electric Power University. Baoding, Hebei 071000,China *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Since the 18th national congress of the communist party of China (CPC), the CPC central committee with Xi Jinping at the core of leadership has launched an anti-graft campaign with an all-inclusive and zero-tolerance attitude. Among all the corrupt behaviors, "family corruption" has undoubtedly become a typical corrupt behavior, which has bad social influence, diverse forms and distinctive characteristics. Family corruption can be divided into three modes according to the characteristics of corruption behavior, namely, common bribery mode, power shadow mode and option investment mode. The factors leading to family corruption are various. We can make a systematic analysis from four aspects: organizational system, social supervision, officials and family ethics. Through the analysis of the factors that induce family corruption, we can actually determine the corresponding governance strategies: improve the system, strengthen supervision, update the concept, and cultivate political ethics. Keywords: family corruption; realistic representation; inducing factors; governance strategy 1. INTRODUCTION 2. THE REALISTIC REPRESENTATION OF FAMILY CORRUPTION Since the 18th national congress of the communist party of China (CPC), the fight against corruption has achieved remarkable results. With the anti-corruption storm advancing, Zhou Yongkang, Ling Jihua, Su Rong, and 2.1. The behavior pattern of family corruption other groups of "big tigers" fall, and family corruption The so-called family corruption refers to the behavior that cases are increasingly surfaced. -

Zhou-Master.Pdf (1.441Mb)

Are You a Good Chinese Musician? The Ritual Transmission of Social Norms in a Chinese Reality Music Talent Show Miaowen Zhou Master’s Thesis in East Asian Culture and History (EAST4591 - 60 Credits) Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2015 © Miaowen Zhou 2015 Are You a Good Chinese Musician? The Ritual Transmission of Social Norms of a Chinese Reality Music Talent Show http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo II Abstract The sensational success of a Chinese reality music talent show, Super Girls’ Voice (SGV), in 2005 not only crowned many unknown Chinese girls/women with the hail of celebrity overnight, but also caused hot debates on many subjects including whether the show triggered cultural, even political democracy in China. 10 years have passed and China is in another heyday of reality music talent shows. However, the picture differs from before. For instance, not everybody can take part in it anymore. And the state television China Central Television (CCTV) joined the competition for market share. It actually became a competitive player of “reality” by claiming to find the best original and creative Chinese musicians whose voices CCTV previously avoided or oppressed. In this thesis, I will examine one CCTV show, The Song of China (SOC), in order to examine what the norms of good Chinese music and musicians are in the context of reality music talent shows. My work will hopefully give you some insights into the characteristics and the wider social and political influences of such reality music talent shows in the post-SGV era. -

Detentions Cast Pall Over Macau's Recovery P7

FLYING EYE HOSPITAL IN RUSSIA SYRIA HALT VIETNAM , MACAU ALEPPO AIRSTRIKES The unique aircraft arrived BRACES Russian and Syrian warplanes in Macau following its sight- FOR halted their airstrikes on Aleppo. saving mission in Shenyang, TYPHOON Moscow described the move as China SARIKA an “humanitarian pause” P2 P12 P14 SYRIA WED.19 Oct 2016 T. 24º/ 28º C H. 80/ 98% facebook.com/mdtimes + 11,000 MOP 7.50 2666 N.º HKD 9.50 FOUNDER & PUBLISHER Kowie Geldenhuys EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Paulo Coutinho www.macaudailytimes.com.mo “ THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGIN’ ” WORLD BRIEFS GAMING AP PHOTO Detentions cast pall CHINA-PHILIPPINES This week’s visit to China by Philippine President P7 Rodrigo Duterte points toward a restoration of over Macau’s recovery trust between the sides following recent tensions over their South China Sea territorial dispute, Chinese official news agency says. More on p11 RENATO MARQUES RENATO CHINA Entertainment giant Wanda is offering producers a rebate of 40 percent to promote its upcoming USD8b movie studio in eastern China in an ambitious bid to establish the complex as a major production base in Asia. More on p10 AP PHOTO THAILAND People waited patiently in long queues outside government banks to secure special commemorative 100 baht currency notes in honor of the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej. BANGLADESH Three Bangladeshi men have been identified as the financiers of the July 1 attack in which a group of assailants tortured and killed 20 hostages at a restaurant in Dhaka, a counterterrorism official says. AP PHOTO NEW ZEALAND A U.S. -

P12 Layout 1

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 19, 2016 INTERNATIONAL Tears and tortoises - Chinese TV unveils graft secrets BEIJING: With a tale of a dead pet tortoise given Three of those “tigers” get camera time in the Zhou “set his expectations upon protection Describing his failings, Sichuan’s Li, given a 13- Buddhist rites and a senior official shedding tears first episode Bai Enpei, the former party boss of from supernatural beings and was widely involved year jail term last year, struggled and failed to for his crimes, state television has begun airing a southwestern Yunnan province; Zhou Benshun, an in superstitious practices”, the narrator says. “After keep back tears. “From a young age I hoped that documentary that takes viewers behind the scenes ex-party chief of northern Hebei province and Li a tortoise died at his home, he specially had scrip- under the leadership of the party ... I could get of some of China’s most dramatic corruption cases. Chuncheng, a former deputy party boss of south- tures transcribed and buried with it.” Zhou even progress for society, make the people happy,” Li The eight-part series that kicked off late on western Sichuan. Bai and Li have both been con- had a nanny for his pets, investigator Wang Han said. “In the end, because of myself, I didn’t get Monday promises an unusual warts-and-all victed, while Zhou awaits trial. The juiciest details told the program. The three disgraced officials all there. I really let the party down. I let the people approach to revealing the story behind the dirty come from the probe into Zhou. -

Life Science and Healthcare Industry

SECTOR ANALYSIS RESEARCH SERIES – LIFE SCIENCE AND HEALTHCARE INDUSTRY Presenters: Eunice Chu, FCCA, Head of Policy, ACCA Hong Kong Alan Lok, CFA, Director, Ethics Education and Professional Standards, Asia-Pacific, CFA Institute Dr Bin Li, Founder & CIO, Lake Bleu Capital Dr Jiaxi Xu, Managing Director & Deputy Head of Research, China Industrial Securities READ THE FULL REPORT Download Report Here https://cfainst.is/3fufojT KEYNOTE Eunice Chu, FCCA Head of Policy, ACCA Hong Kong Life Sciences and Healthcare industry By Eunice Chu Head of Policy, ACCA Hong Kong © ACCA Public Overview Non-discretionary industry 10% of global GDP was spent on it … .. And it is snowballing with aging population . Producers are competing on efficient services . Consumers are educated and empowered by internet . Governments strikes a balance between overregulation and the free market © ACCA Public Three categories . Drug producers Demand . Health care providers Patients . Medical equipment and supplies manufacturers © ACCA Public Megatrends – the 3 Cs Consolidation – M&A Cover – insurance Change . Reduced competition . Price at health . Government policies may push up prices condition thanks to changes greatly affect technologies health care industry © ACCA Public Long-term drivers: the 3 Ds Demographics Diseases Development . Aging population . Diabetes, heart . Technologies attack , stroke, . Co-payment system cancer – on the rise . Computerized . Step-down care health records © ACCA Public • Level of demand • Dominant player? • R&D convert into • Future growth • Barriers to entry patentable • Population mix • Competitive edge products • History of failure drugs recall? Demand\ Market Track Universal Growth Structure Records analysis for healthcare companies • R&D investment • Staff treated \paid • Net margins fairly? • Extended trials for • Medicines are drugs / devices? thoroughly tested & compliant? Financial ESG Performance Compliance © ACCA Public 9 Analysis of Three Segments © ACCA Public 1. -

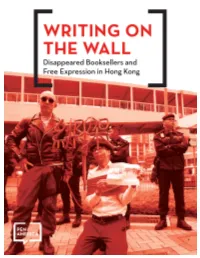

Disappeared Booksellers and Free Expression in Hong Kong 1

Writing on the Wall: Disappeared Booksellers and Free Expression in Hong Kong 1 WRITING ON THE WALL Disappeared Booksellers and Free Expression in Hong Kong November 5, 2016 © 2016 PEN America. All rights reserved. PEN America stands at the intersection of literature and human rights to protect open expression in the United States and worldwide. We champion the freedom to write, recognizing the power of the word to transform the world. Our mission is to unite writers and their allies to celebrate creative expression and defend the liberties that make it possible. Founded in 1922, PEN America is the largest of more than 100 centers of PEN International. Our strength is in our membership—a nationwide community of more than 4,000 novelists, journalists, poets, essayists, playwrights, editors, publishers, translators, agents, and other writing professionals. For more information, visit pen.org. Cover photograph: Artist Kacey Wong protests the Causeway Bay Books disappearances bound and gagged, sporting a red noose bearing the Chinese characters for "abduction." The sign in his hand says "Hostage is well. " Photo courtesy of Kacey Wong. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 “One Country, Two Systems” Under Threat ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Hong Kong’s Legal Framework -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 195 International Seminar on Education Research and Social Science (ISERSS 18) Research on “Two Targeted Tasks” Training Mode for Higher Vocational Talents Jing Luo Xiaoxu Xiao Guangzhou Nanyang College Guangzhou International Economics College Guangzhou 510925 Guangzhou 510540 Abstract—In higher vocational colleges, students' job way to gain instant effect in vocational education is to conduct positions scarcely match their professions, the career competence targeted connection between school and enterprise as well as of graduates does not meet the requirements of enterprises, and profound integration of production and education. We should these students are facing heavy pressure of employment. In view focus on targeted education, take ourselves as part of the of these problems, this article analyzes the characteristics of enterprises, take their thoughts, needs and standards seriously, training mode in vocational colleges, and explores "two targeted and apply for employment actively and humbly, so as to open tasks", a new model which refers to school-enterprise targeted the channel for higher vocational talents, and put the targeted connection and targeted education. By making specialty setup connection and education into practice, including colleges and connected with industry development, curriculum reform enterprises. connected with career competence, teaching process connected with the producing process, and technological service connected with the enterprise requirement, the four aspects of connection I. "THREE DIFFICULTIES" IN THE PROCESS OF TRAINING are obtained, and the aforementioned “two targeted tasks” are HIGHER VOCATIONAL STUDENTS achieved. "Three difficulties" refers to problems occur in the process Keywords—targeted education, connection, training objective, of training higher vocational students recent years. -

Airport Industry Innovation Forum 2019

Airport Industry Innovation Forum 2019 Intelligence Leading Future Airport Civil Aviation Ecosystem Organizer: Media Support : Shanghai·China October 23rd -24th,2019 Conference introduction Airport is the end of every journey and the beginning of every journey. How many takeoffs and landings, take-offs and turn-offs an airport will experience in its lifetime may be a secret we don't know - what about the airport itself? From October 23 to 24, 2019, the "Air- port Industry Innovation Forum 2019" will be held in Shanghai with the theme of "Intelligent Airport Future, Building Aviation Ecology". We hope that through this Forum, we can gather all the subdi- visions of the airport industry and show you a deep insight into the future trends, products and technologies of the airport industry, discuss the future development of the airport industry and stimulate civil aviation cooperation and innova- tion.150+ global airports and well-known enterprises gathered to share airport development trends and industry hotspots. Background The 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China has put forward that China's economy has entered a stage of high-quality development. In the Outline for Building a Civil Aviation Power in the New Era issued by the Civil Aviation Administration, it is clearly pointed out that airport planning and construc- tion should be promoted with high quality to build a safe, green, intelligent and humanistic airport. The construction of "four airports" involves 25 new technologies in four categories: airport operation safety, efficiency, service and construction safety. The relevant departments and bureaus are also actively improving supporting policies. -

Explaining Variation in Adoption and Implementation Of

EXPLAINING VARIATION IN ADOPTION AND IMPLEMENTATION OF ANTI-CORRUPTION POLICIES _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Public Affairs _____________________________________________________ by Kyoung-sun Min Dr. Alasdair S. Roberts and Dr. Mary Stegmaier, Dissertation Supervisors July 2018 © Copyright by Kyoung-sun Min 2018 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled EXPLAINING VARIATION IN ADOPTION AND IMPLEMENTATION OF ANTI-CORRUPTION POLICIES presented by Kyoung-sun Min, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Mary Stegmaier Professor Alasdair S. Roberts Professor Lael Keiser Professor Judith Stallmann To Grace ACKNOWLEDGMENTS While writing this dissertation, I have had the benefit of comments from great teachers. It is difficult to express in words my gratitude to Professor Alasdair S. Roberts. He has taught me how to study research questions in broader contexts. Without his guidance, this dissertation would not have been written. I am particularly grateful to Professor Mary Stegmaier. As my co-advisor, she has helped me in many of my hours of need. I am truly indebted to her. I must also thank Professors Lael Keiser and Judith Stallmann for their support and comments. I wish to thank Professor Colleen Heflin, who has firmly believed in my potential. This essay is a small step toward living up to her expectations. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................... -

“Unavoidable”? - Tacit Rationality and the Reinforcement of Informal Institutions in China

Why does Corruption Appear to be “Unavoidable”? - Tacit Rationality and the Reinforcement of Informal Institutions in China Von der Fakultät für Gesellschaftswissenschaften der Universität Duisburg-Essen zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Dr. phil genehmigte Dissertation von GE, Ningjing aus Shenyang, V. R. China 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Christiansen, Flemming 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Ngo, Tak-Wing Tag der Disputation: 11/05/2020 Diese Dissertation wird über DuEPublico, dem Dokumenten- und Publikationsserver der Universität Duisburg-Essen, zur Verfügung gestellt und liegt auch als Print-Version vor. DOI: 10.17185/duepublico/71802 URN: urn:nbn:de:hbz:464-20200525-123450-4 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Contents Abstract i Zusammenfassung iii Preface v Abbreviations xiii Introduction 1 Topic and Hypothesis 1 Theories of Corruption in View of Hypothesis 5 Research Significance 19 Chapter 1 Theoretical Framing and Methodological Approach 27 1.1 Theoretical Framing of the Research 27 1.2 Applying Tacit Rationality to Explaining Corruption in China: An Alternative View of the Reinforcement of Informal Institutions, Cooperative Commitment and Transactional Corruption 40 1.3 Methodological Approach: Critical Discourse Analysis 50 Chapter 2 Perceiving the Idealised Values Associated with CPC Cadres’ Multiple Roles through a Critical Examination of Official and Unofficial Discourses about Corruption 65 2.1 Loyalty to the Party Organisation Associated with the Cadres’ Political Role 72 2.2 Renqing and Mianzi Associated with the Cadres’ Social Role 79 -

Case Study of Xi Jinping's Anti

Afro Asian Journal of Social Sciences Volume IX, No IV Quarter IV 2018 ISSN: 2229 – 5313 THE CAPITAL OF PUBLIC AGENDA-SETTING: CASE STUDY OF XI JINPING’S ANTI-GRAFT CAMPAIGN Hagan Sibiri Ph.D. Candidate in International Politics at the School of International Relations and Public Affairs, Fudan University, Shanghai, China ABSTRACT The article examines (within the context of agenda-setting functions of the media) the influence of the Chinese mass media in public perception of corruption. It not only charts on the overall trend of Corruption Perception since Xi Jinping launched his far-reaching anti- graft drive but also demonstrates how the media is being required and used as a propaganda tool in the anti-graft campaign. The article largely draws upon existing survey data on corruption perception and news reports from 2012 to 2017. The analysis shows a plummet in public perception of corruption from the onset of Xi’s anti-graft crackdown. However, a series of CPC and state-backed anti-graft mass media propaganda have had some positive influence on public perception of corruption.Therefore, by inference, the best attributable explanatory factor of China’s recent improved Corruption Perception performance is the mass media anti-graft propaganda. Keywords: China, Mass media, Public agenda-setting, Public perception, Anti-graft, Xi Jinping. 1. Introduction The ability of the mass media to set the public agenda (public opinion)on key issues is an “immense and well-documented influence” (McCombs 2004). The public does not only access and consume