Operational Guidance Note

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xi Jinping's War on Corruption

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2015 The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption Harriet E. Fisher University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Harriet E., "The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption" (2015). Honors Theses. 375. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/375 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping’s War on Corruption By Harriet E. Fisher A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies at the Croft Institute for International Studies and the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi May 2015 Approved by: ______________________________ Advisor: Dr. Gang Guo ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Kees Gispen ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Peter K. Frost i © 2015 Harriet E. Fisher ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii For Mom and Pop, who taught me to learn, and Helen, who taught me to teach. iii Acknowledgements I am indebted to a great many people for the completion of this thesis. First, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Gang Guo, for all his guidance during the thesis- writing process. His expertise in China and its endemic political corruption were invaluable, and without him, I would not have had a topic, much less been able to complete a thesis. -

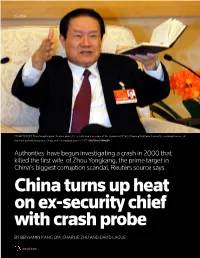

China Turns up Heat on Ex-Security Chief with Crash Probe

CHINA PRIME TARGET: Zhou Yongkang was head of domestic security and a member of the Communist Party Standing Politburo Committee, making him one of the most powerful people in China, until he stepped down in 2012. REUTERS/STRINGER Authorities have begun investigating a crash in 2000 that killed the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, the prime target in China’s biggest corruption scandal, Reuters source says. China turns up heat on ex-security chief with crash probe BY BENJAMIN KANG LIM, CHARLIE ZHU AND DAVID LAGUE SPECIAL REPORT 1 CHINA’S POWER STRUGGLE BEIJING/HONG KONG, SEPTEMBER 12, 2014 ittle is known about the exact circum- stances in which Wang Shuhua was Lkilled. What has been reported, in the Chinese media, is that she died in a road ac- cident sometime in 2000, shortly after she was divorced from her husband. And that at least one vehicle with a military license plate may have been involved in the crash. Fourteen years later, investigators are looking into her death. Their sudden inter- est has nothing to do with Wang herself. It has to do with the identity of her ex-hus- band – once one of China’s most powerful men and now the prime target in President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign. Investigators are probing the death of the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, China’s HUNTING TIGERS: President Xi Jinping has launched the biggest corruption crackdown since the retired security czar, a source with di- communists came to power in 1949, going after “tigers” or high-ranking officials as well as “flies”. -

China's Domestic Politicsand

China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China edited by Jung-Ho Bae and Jae H. Ku China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China 1SJOUFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFECZ ,PSFB*OTUJUVUFGPS/BUJPOBM6OJGJDBUJPO ,*/6 1VCMJTIFS 1SFTJEFOUPG,*/6 &EJUFECZ $FOUFSGPS6OJGJDBUJPO1PMJDZ4UVEJFT ,*/6 3FHJTUSBUJPO/VNCFS /P "EESFTT SP 4VZVEPOH (BOHCVLHV 4FPVM 5FMFQIPOF 'BY )PNFQBHF IUUQXXXLJOVPSLS %FTJHOBOE1SJOU )ZVOEBJ"SUDPN$P -UE $PQZSJHIU ,*/6 *4#/ 1SJDF G "MM,*/6QVCMJDBUJPOTBSFBWBJMBCMFGPSQVSDIBTFBUBMMNBKPS CPPLTUPSFTJO,PSFB "MTPBWBJMBCMFBU(PWFSONFOU1SJOUJOH0GGJDF4BMFT$FOUFS4UPSF 0GGJDF China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China �G 1SFGBDF Jung-Ho Bae (Director of the Center for Unification Policy Studies at Korea Institute for National Unification) �G *OUSPEVDUJPO 1 Turning Points for China and the Korean Peninsula Jung-Ho Bae and Dongsoo Kim (Korea Institute for National Unification) �G 1BSUEvaluation of China’s Domestic Politics and Leadership $IBQUFS 19 A Chinese Model for National Development Yong Shik Choo (Chung-Ang University) $IBQUFS 55 Leadership Transition in China - from Strongman Politics to Incremental Institutionalization Yi Edward Yang (James Madison University) $IBQUFS 81 Actors and Factors - China’s Challenges in the Crucial Next Five Years Christopher M. Clarke (U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research-INR) China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual Report 2019

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 18, 2019 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: https://www.cecc.gov VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 18, 2019 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: https://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 36–743 PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate JAMES P. MCGOVERN, Massachusetts, MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Co-chair Chair JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio TOM COTTON, Arkansas THOMAS SUOZZI, New York STEVE DAINES, Montana TOM MALINOWSKI, New Jersey TODD YOUNG, Indiana BEN MCADAMS, Utah DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California CHRISTOPHER SMITH, New Jersey JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon BRIAN MAST, Florida GARY PETERS, Michigan VICKY HARTZLER, Missouri ANGUS KING, Maine EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Department of State, To Be Appointed Department of Labor, To Be Appointed Department of Commerce, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed JONATHAN STIVERS, Staff Director PETER MATTIS, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT C O N T E N T S Page I. -

610 Office” That I Witnessed by Hao Fengjun

EXHIBIT C The “610 Office” that I Witnessed By Hao Fengjun First of all, let me express my sincere gratitude to the invitation of Dr. Charles, the Vice President of the Human Rights Committee of the European Parliament. As a result I have this opportunity to briefly submit to the Committee what activities the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is currently engaged in through my personal experience. 1. The “610 Office” Truly Exists In 1994 I graduated from the Law Department in Nankai University in Tianjin. After graduation, I was assigned to work at Tianjin City Public Security Bureau. In October 2000, I was transferred to the “610 Office” under Tianjin Public Security Bureau. Since the Staffing Committee of the Tianjin City Party Committee had not granted the establishment of such a “610” organization at the time, the “610 Office” did not have any legal status. As a result, our personnel files were kept at the original work units. 1) Naming of the “610 Office” From 1999 to 2003, the “610 Office” was called the “Office to Deal with the Falun Gong Problem.” From 2003 to present, it is known as “The Office of Preventing and Handling Evil Cult Crimes (Bureau or Department)”. 2) Structure of the “610 Office” Nationwide Up until now, the CCP has never acknowledged the existence of the “610 Office” – an organization similar in nature to Nazi Germany’s Gestapo, which specializes in persecuting Falun Gong and other religious dissidents. Recently at an international press conference, the assistant to the CCP’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sheng Guofang, again publicly denied the existence of the “610 Office.” Many who do not know the true nature of the CCP may well believe the lie that is repeated a thousand times by the CCP. -

Prepared Statement of Xiaorong Li, Independent Scholar

Prepared Statement of Xiaorong Li, Independent Scholar Congressional-Executive Commission on China Roundtable on "Current Conditions for Human Rights Defenders and Lawyers in China, and Implications for U.S. Policy" June 23, 2011 The serious backsliding of the Chinese government’s human rights records had started before the 2008 Summer Olympics, highlighted with the jailing of activists Hu Jia, Huang Qi, and many others, the torture and disappearance of lawyer Gao Zhisheng, the imprisonment of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo and house arrest of his wife, both incommunicado, and the house arrest of Chen Guangcheng after his release. Yesterday’s release of the artist Ai Weiwei on bail awaiting for trial was in the same fashion as his arrest: with disregard of the Chinese law. All these took place in the larger context of severe restrictions on freedom of expression and association, repression against religious and ethnic minorities, and significant roll-back on rule of law reform. Since February, several hundreds of people have been harassed or persecuted in one of the harshest crackdowns in recent years when the Chinese government tried to stamp out any sparks for protests in the Tunisia-style “Jasmine Revolution” after online calls first appeared. According to information documented by the group Chinese Human Rights Defenders, the Chinese government has criminally detained a total of 49 individuals, outside the Tibet and Xinjiang regions. As of today, nine of them have been formally arrested, three sent to Re-education through Labor (RTL) camps, 32 have been released but most of them not free: out of which 22 have been released on bail to await trial, while four remain in criminal detention. -

Chinese Politics in the Xi Jingping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership

CHAPTER 1 Governance Collective Leadership Revisited Th ings don’t have to be or look identical in order to be balanced or equal. ڄ Maya Lin — his book examines how the structure and dynamics of the leadership of Tthe Chinese Communist Party (CCP) have evolved in response to the chal- lenges the party has confronted since the late 1990s. Th is study pays special attention to the issue of leadership se lection and composition, which is a per- petual concern in Chinese politics. Using both quantitative and qualitative analyses, this volume assesses the changing nature of elite recruitment, the generational attributes of the leadership, the checks and balances between competing po liti cal co ali tions or factions, the behavioral patterns and insti- tutional constraints of heavyweight politicians in the collective leadership, and the interplay between elite politics and broad changes in Chinese society. Th is study also links new trends in elite politics to emerging currents within the Chinese intellectual discourse on the tension between strongman politics and collective leadership and its implications for po liti cal reforms. A systematic analy sis of these developments— and some seeming contradictions— will help shed valuable light on how the world’s most populous country will be governed in the remaining years of the Xi Jinping era and beyond. Th is study argues that the survival of the CCP regime in the wake of major po liti cal crises such as the Bo Xilai episode and rampant offi cial cor- ruption is not due to “authoritarian resilience”— the capacity of the Chinese communist system to resist po liti cal and institutional changes—as some foreign China analysts have theorized. -

Falun Gong in China

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 12 Issue 1 Article 6 6-2018 Cold Genocide: Falun Gong in China Maria Cheung University of Manitoba Torsten Trey Doctors Against Forced Organ Harvesting David Matas University of Manitoba Richard An EME Professional Corp Legal Services Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Cheung, Maria; Trey, Torsten; Matas, David; and An, Richard (2018) "Cold Genocide: Falun Gong in China," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 12: Iss. 1: 38-62. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.12.1.1513 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol12/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cold Genocide: Falun Gong in China Acknowledgements This article is dedicated to the Chinese citizens who were innocently killed for their spiritual beliefs. This article is available in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol12/iss1/6 Cold Genocide: Falun Gong in China Maria Cheung University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Torsten Trey Doctors Against Forced Organ Harvesting Washington, D.C., USA David Matas University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Richard An York University Toronto, Ontario, Canada Introduction The classical school of genocide studies which traces back to Raphael Lemkin focuses on eradication of a group through the mass murder of its members in a short period. -

Chapter 3 China: Xi Jinping's Administration— Proactive Policies

Chapter 3 China: Xi Jinping’s Administration— Proactive Policies at Home and Abroad or China, 2014 was a year when initiatives of the Xi Jinping administration Fcame to the forefront. In domestic politics, it was a year of important changes, as the anti-corruption campaign continued to make itself felt, resulting, for example, in Zhou Yongkang, a former member of the Politburo Standing Committee, and Xu Caihou, former vice chairman of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Military Commission (CMC), being expelled from the party. Xi Jinping, who was already president as well as general secretary of the party, took the position of chairman of the new National Security Commission and created a number of small leading groups, part of his efforts to strengthen his structural authority. Meanwhile elements of instability grew as well, such as the number of bombings that took place in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, and the CPC is cracking down vigorously. President Xi has assertively engaged in foreign policy, leading at times to strong unilateral positions such as China’s location of oil drilling equipment in the South China Sea. China is seeking to form “a new type of major-power relations” with the United States, but China’s actions in the South China Sea and the confrontation over cyber spying make it unclear whether China will be able to achieve the kind of US-China relations it desires. President Xi is also engaging in periphery diplomacy, seeking to ensure China’s peaceful development by reinforcing its economic relations with its neighbors and calling for an Asian New Security Concept, while strengthening its criticism of the system of alliances centered on the United States. -

Cleaning the Security Apparatus Before the Two Meetings

ASIA PROGRAMME CLEANING THE SECURITY APPARATUS BEFORE THE TWO MEETINGS BY ALEX PAYETTE PH.D, CEO CERCIUS GROUP ADJUNCT PROFESSOR, GLENDON COLLEGE MAY 2020 ASIA FOCUS #139 l’IRIS ASIA FOCUS #139 – ASIA PROGRAMME / May 2020 n April 19 2020, Sun Lijun 孙力军 was put under investigation. Sun is the mishu of Meng Jianzhu 孟建柱, Party secretary of the Central Political and Legal Affairs o Commission [zhengfa] from 2012 to 2017, and a close ally of Politburo member Han Zheng 韩正, who is also a full member of Jiang Zemin’s 江泽民 Shanghai Gang 上海帮 . His arrest, which happened only one day after 15 pro-democracy activists were arrested in Hong Kong1, almost coincided with his return from Wuhan – as part of the Covid-19 containment steering group 中央赴湖北指导组. To this effect, it is evident that Sun’s investigation and arrest have been in motion for quite a while now. With Sun out of play, the former public security “tsar” Zhou Yongkang 周永康 has effectively lost most of his tentacles on the public security system. That said, Sun’s arrest might not even be the most important news shaking up the public security apparatus ahead of the upcoming “Two Meetings” 两会. CUTTING THE ROOTS As it is customary with Cadres working for public security, State security and national Defence, Sun Lijun’s public profile is quite limited. Sun, who studied in Australia, majored in public health and urban management, a very interesting choice especially considering the current pandemic. Sun was primarily active in Shanghai, and held a number of notable posts in his career including: • Director of the Hong Kong affairs office of the Ministry of Public Security from 2016 until his arrest; • Deputy director of the infamous “610” unit 中央610办公室– also known as the Central Leading Group on Preventing and Dealing with Heretical Religions 中央防范 和处理邪教问题领导小组2; • Director of the No. -

The Illegality of China's Falun Gong Crackdown and Its Relevance to the Recent Political Turmoil

The illegality of China's Falun Gong crackdown and its relevance to the recent political turmoil Hearing of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, December 18, 2012 Written Statement by Yiyang Xia, Senior Director of Policy and Research at the Human Rights Law Foundation and Director of the Investigation Division for the World Organization to Investigate the Persecution of Falun Gong I would like to express my appreciation to the members of CECC, particularly Chairman Smith and Co-Chairman Brown, for holding this hearing for FLG In recent years, the world has witnessed deteriorating human rights conditions and growing disregard for the rule of law in China, whether it is in cases involving activists, democracy advocates, or even high-ranking officials. But what are the underlying causes of the current situation? In essence, it began 13 years ago when the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) launched its campaign to eliminate Falun Gong, a spiritual practice with followers numbering in the tens of millions. In my remarks, I will explore three dimensions of the persecution: 1. How the party has systematically violated Chinese laws for the purposes of implementing the persecution of Falun Gong practitioners. 2. How Wang Lijun, a centerpiece of recent political turmoil in China, was involved in the persecution of Falun Gong practitioners and organ transplant abuses. 3. The challenge facing the new leadership when it comes to the ongoing campaign against Falun Gong. How the persecution operates without a legal basis The Chinese government never legally banned Falun Gong and there is, in fact, no law on the books prohibiting this religious practice. -

Political Context Following the Events in the Middle East

CHINA OBSERVATORY FOR thE PROTEctiON OF humAN Rights DEFENDERS ANNUAL REPORT 2011 In China, human rights activities and fundamental freedoms remained severely restricted throughout 2010 and 2011. In addition, the Chinese authorities increased their repression against any form of dissent in response to anonymous online calls for a “Jasmine Revolution” that started in February 2011 following the events in the Middle East and North Africa. In that context, human rights defenders, including the signatories of “Charter 08”, human rights lawyers as well as defenders working on HIV/AIDS, who denounced forced evictions, corruption and who questioned the Government’s role in various scandals, continued to be subjected to various acts of harassment and intimidation, including arbitrary detention and enforced disappear- ance. The authorities also continued to crackdown on defenders and restrict freedoms of expression, assembly and association on the eve of key sensitive anniversaries and events, such as the Shanghai World Expo 2010. IA S Political context A Following the events in the Middle East and North Africa in early 2011, Chinese authorities became increasingly concerned that the revolutions may have a spill-over effect in China as well. Their reactions especially intensified after an anonymous call online on February 19, 2011, urging people to start a “Jasmine Revolution-style uprising”, similar to those in Tunisia and Egypt. The online post urges protestors to chant slogans on February 20, 2011, in several cities across China. Although faced with a massive response from the police, another online post called on people to march peacefully on February 27 to certain central or symbolic places.