White's Poetics: Patrick White Through Mikhail Bakhtin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Use of Theses

THESES SIS/LIBRARY TELEPHONE: +61 2 6125 4631 R.G. MENZIES LIBRARY BUILDING NO:2 FACSIMILE: +61 2 6125 4063 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY EMAIL: [email protected] CANBERRA ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA USE OF THESES This copy is supplied for purposes of private study and research only. Passages from the thesis may not be copied or closely paraphrased without the written consent of the author. FINDING A PLACE: LANDSCAPE AND THE SEARCH FOR IDENTITY IN THE EARLY NOVELS OF PATRICK WHITE Y asue Arimitsu A thesis submitted for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS at the Australian National University December 1985 11 Except where acknowledgement is made, this thesis is my own work. Yasue Arimitsu Ill ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Acknowledgements are due to many people, without whose assistance this work would have proved more difficult. These include Dr Livio Dobrez and Dr Susan McKer nan, whose patience was unfailing; Dr Bob Brissenden, who provided initial encourage ment; Mr Graham Cullum, for advice and assistance; Professor Ian Donaldson, for his valuable comments; and Jean Marshall, for her kind and practical support. Special thanks must be given to the typist, Norma Chin, who has worked hard and efficiently, despite many pressures. My gratitude is also extended to my many fellow post-graduates, who over the years have sustained, helped and inspired me. These in clude especially Loretta Ravera Chion, Anne Hopkins, David Jans, Andrew Kulerncka, Ann McCulloch, Robert Merchant, Julia Robinson, Leonie Rutherford and Terry Wat- son. Lastly I would like to thank the Australia-Japan Foundation, whose generous financial support made this work possible and whose unending concern and warmth proved most encouraging indeed. -

Books at 2016 05 05 for Website.Xlsx

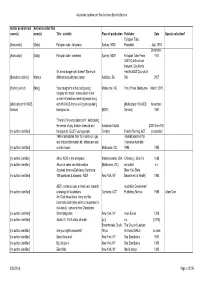

Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives Book Collection Author or editor last Author or editor first name(s) name(s) Title : sub-title Place of publication Publisher Date Special collection? Fallopian Tube [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : fallopiana Sydney, NSW Pamphlet July, 1974 December, [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : madness Sydney, NSW Fallopian Tube Press 1974 GLBTIQ with cancer Network, Gay Men's It's a real bugger isn't it dear? Stories of Health (AIDS Council of [Beresford (editor)] Marcus different sexuality and cancer Adelaide, SA SA) 2007 [Hutton] (editor) [Marg] Your daughter's at the door [poetry] Melbourne, VIC Panic Press, Melbourne March, 1975 Inequity and hope : a discussion of the current information needs of people living [Multicultural HIV/AIDS with HIV/AIDS from non-English speaking [Multicultural HIV/AIDS November, Service] backgrounds [NSW] Service] 1997 "There's 2 in every classroom" : Addressing the needs of gay, lesbian, bisexual and Australian Capital [2001 from 100 [no author identified] transgender (GLBT) young people Territory Family Planning, ACT yr calendar] 1995 International Year for Tolerance : gay International Year for and lesbian information kit : milestones and Tolerance Australia [no author identified] current issues Melbourne, VIC 1995 1995 [no author identified] About AIDS in the workplace Massachusetts, USA Channing L Bete Co 1988 [no author identified] Abuse in same sex relationships [Melbourne, VIC] not stated n.d. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome : [New York State [no author identified] 100 questions & answers : AIDS New York, NY Department of Health] 1985 AIDS : a time to care, a time to act, towards Australian Government [no author identified] a strategy for Australians Canberra, ACT Publishing Service 1988 Adam Carr And God bless Uncle Harry and his roommate Jack (who we're not supposed to talk about) : cartoons from Christopher [no author identified] Street Magazine New York, NY Avon Books 1978 [no author identified] Apollo 75 : Pix & story, all male [s.l.] s.n. -

Patrick White: Twyborn Moments of Grace

Patrick White: Twyborn Moments of Grace By the end of the 1970s it was clear that critics were deeply divided over the nature of Patrick White's work and his achievement. At that time, I attempted to identify their fundamental differences by asking whether White was to be seen as a traditional novelist with a religious or theosophical view of life, or as a sophisticated, ironical modern mistrustful of language and sceptical of ever being able to express what might lie beyond words?1 Since then, literary criticism has registered some changes, and shocks. Indeed that term, 'literary criticism', has come to suggest the kind, or kinds, of exegesis and evaluation that prevailed in the ages that preceded our own brave new theoretical world. (I speak in general terms but have contemporary Australian academia specifically in mind.) How, I wonder, would a new reader, one coming to White for the first time through his most recent novel, The Twyborn Affair (1979), perceive him? In imagining this 'new' reader I have in mind a younger generation, particularly of students, who need not have encountered White's earlier novels and criticisms of them, and for whom the terms and concerns of Anglo-American New Criticism which affected the academic reception of White's work from at least the 1960s on are likely to be less immediate than those of Continental and North American theorists who have been influential during the last decade or more; for instance, Mikhail Bakhtin, who looms large on the program for this conference and in the October 1984 issue of PMI.A. -

Biographical Information

BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION ADAMS, Glenda (1940- ) b Sydney, moved to New York to write and study 1964; 2 vols short fiction, 2 novels including Hottest Night of the Century (1979) and Dancing on Coral (1986); Miles Franklin Award 1988. ADAMSON, Robert (1943- ) spent several periods of youth in gaols; 8 vols poetry; leading figure in 'New Australian Poetry' movement, editor New Poetry in early 1970s. ANDERSON, Ethel (1883-1958) b England, educated Sydney, lived in India; 2 vols poetry, 2 essay collections, 3 vols short fiction, including At Parramatta (1956). ANDERSON, Jessica (1925- ) 5 novels, including Tirra Lirra by the River (1978), 2 vols short fiction, including Stories from the Warm Zone and Sydney Stories (1987); Miles Franklin Award 1978, 1980, NSW Premier's Award 1980. AsTLEY, Thea (1925- ) teacher, novelist, writer of short fiction, editor; 10 novels, including A Kindness Cup (1974), 2 vols short fiction, including It's Raining in Mango (1987); 3 times winner Miles Franklin Award, Steele Rudd Award 1988. ATKINSON, Caroline (1834-72) first Australian-born woman novelist; 2 novels, including Gertrude the Emigrant (1857). BAIL, Murray (1941- ) 1 vol. short fiction, 2 novels, Homesickness (1980) and Holden's Performance (1987); National Book Council Award, Age Book of the Year Award 1980, Victorian Premier's Award 1988. BANDLER, Faith (1918- ) b Murwillumbah, father a Vanuatuan; 2 semi autobiographical novels, Wacvie (1977) and Welou My Brother (1984); strongly identified with struggle for Aboriginal rights. BAYNTON, Barbara (1857-1929) b Scone, NSW; 1 vol. short fiction, Bush Studies (1902), 1 novel; after 1904 alternated residence between Australia and England. -

Patrick White's Fiction Patrick White's Fiction

PATRICK WHITE'S FICTION PATRICK WHITE'S FICTION The Paradox of Fortunate Failure Carolyn Bliss Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 978-1-349-18329-6 ISBN 978-1-349-18327-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-18327-2 © Carolyn Jane Bliss 1986 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1986 978-0-333-38869-3 All rights reserved. For information, write: St. Martin's Press, Inc., 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010 First published in the United States of America in 1986 ISBN 978-0-312-59805-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bliss, Carolyn Jane, 1947- Patrick White's fiction: the paradox of fortunate failure. Bibliography: p. Includes index. I. White, Patrick, 1912- -Criticism and interpretation. 2. Failure (Psychology) in literature. I. Title. PR9619.3.W5Z584 1986 823 85-14608 ISBN 978-0-312-59805-1 To Jim, who understood how much it meant to me Contents Preface lX Acknowledgements Xlll List of Abbreviations XV 1 Australia: the Mystique of Failure 1 2 The Early Works: Anatomy of Failure 15 Happy Valley 15 The Living and the Dead 24 The Aunt's Story 35 TheTreeofMan 49 3 The Major Phase: the Mystery of Failure 60 Voss 61 Riders in the Chariot 82 The Solid Mandala 99 The Vivisector 115 4 The Later Works: the State of Failure 133 The Eye ofthe Storm 136 A Fringe ofLeaves 153 The TwybornAffair 168 5 Style and Technique: the Discipline of Failure 184 Stylistic preferences 187 Narrative stance 192 Imagery and structure 197 Genre and tradition 200 The shape of failure 204 Vll Vlll Contents Notes 208 Bibliography 232 Index 249 Preface The 1973 award of the Nobel Prize for literature to the Australian novelist Patrick White focused world attention on a body of fiction which many believe will one day rank with the best produced in the twentieth century. -

“RUBBED by the WARMING VIOLINS” the Open University “I Can't Have Enough of Music,” Declared Patrick White Bluntly In

Cercles 26 (2012) !"!"##$%&#'&()$&*+!,-./&0-12-.3#! &,"3-4&+.%&5+(!-46&*)-($& ! 7-1.+&!-4)+!%3& !"#$%&#'$(')*#+,)-.$ ! !"#!$%&'(!)%*+!+&,-.)!,/!0-12$34!5+$6%7+5!8%(72$9!:)2(+!;6-&(6<!2&!%!6+((+7!,/! =! >-&+! ?@A?! (,! )21! $6,1+! /72+&5! 8+..<! B%76%&5! CDEFF! G=HI! D%&<! ,/! )21! /2$(2,&%6!$)%7%$(+71!+JK7+11!()+!1%0+!1+&(20+&(I!L,7!E-&(!D%7,!2&!()+!1),7(! 1(,7<3!"M)+!L-66!N+66<34!0-12$!21!"0,7+!&,-721)2&.!()%&!/,,54!C/0123-00,!@OH3! P)26+! B+&+7%6! Q,9,6&29,*! 2&! !"#$ 45'-6,$ 7-0+.! /2&51! 2(! "52//2$-6(! (,! +1$%K+! /7,0! 0-12$I! D-12$! K-71-+14! CR=AHI! E6(),-.)! S-7(6+! T-//2+65! 2&! !"#$ 8)*),#1-0+! 5,+1! &,(! -&5+71(%&5! 0-12$3! "()+! 25+%! ,/! 2(4! 7+/7+1)+1! )20! CUVHI! M,KK3!()+!0-12$!0%1(+7!2&!80,,3!+*+&!57+%01!,/!"%&!25+%6!1(%(+!2&!P)2$)!()+! ,//2$2%6!(,&.-+!C21H!0-12$4!C=OHI!! D-12$!P%1!,/!()+!-(0,1(!20K,7(%&$+!(,!:)2(+I!S+!1K,9+!,&!%!&-0;+7!,/! ,$$%12,&1!,/!-12&.!2(!%1!%&!%25!2&!)21!P72(2&.3!%!7+$,752&.!,/!,&+!,/!N%7(W9'1! *2,62&! $,&$+7(,1! P2()! X+)-52! D+&-)2&! %1! 1,6,21(! )+6K2&.! )20! (,! /2&5! ()+! 72.)(!+&52&.!/,7!80,,3!/,7!+J%0K6+!C:S#MY3!9:3;,!?U?HI!S21!(-7&!,/!K)7%1+!%&5! -1+!,/!7)<()0!,P+1!0-$)!(,!()+!0-12$!()%(!/266+5!)21!62/+I!M)+!&,*+61!%7+! 62;+7%66<!1K72&96+5!P2()!0-12$%6!7+/+7+&$+1!%&5!%66-12,&1Z

Satire and Parody in the Novels of Patrick White

Contrivance, Artifice, and Art: Satire and Parody in the Novels of Patrick White James Harold Wells-Green 0 A thesis presented for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication, University of Canberra, June 2005 ABSTRACT This study arose out of what I saw as a gap in the criticism of Patrick White's fiction in which satire and its related subversive forms are largely overlooked. It consequently reads five of White's post-1948 novels from the standpoint of satire. It discusses the history and various theories of satire to develop an analytic framework appropriate to his satire and it conducts a comprehensive review of the critical literature to account for the development of the dominant orthodox religious approach to his fiction. It compares aspects of White's satire to aspects of the satire produced by some of the notable exemplars of the English and American traditions and it takes issue with a number of the readings produced by the religious and other established approaches to White's fiction. I initially establish White as a satirist by elaborating the social satire that emerges incidentally in The Tree of Man and rather more episodically in Voss. I investigate White's sources for Voss to shed light on the extent of his engagement with history, on his commitment to historical accuracy, and on the extent to which this is a serious high-minded historical work in which he seeks to teach us more about our selves, particularly about our history and identity. The way White expands his satire in Voss given that it is an eminently historical novel is instructive in terms of his purposes. -

Modern Australian Literature

Modern Australian Literature Catalogue 240 September 2020 TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE Unless otherwise described, all books are in the original cloth or board binding, and are in very good, or better, condition with defects, if any, fully described. Our prices are nett, and quoted in Australian dollars. Traditional trade terms apply. Items are offered subject to prior sale. All orders will be confirmed by email. PAYMENT OPTIONS We accept the major credit cards, PayPal, and direct deposit to the following account: Account name: Kay Craddock Antiquarian Bookseller Pty Ltd BSB: 083 004 Account number: 87497 8296 Should you wish to pay by cheque we may require the funds to be cleared before the items are sent. GUARANTEE As a member or affiliate of the associations listed below, we embrace the time-honoured traditions and courtesies of the book trade. We also uphold the highest standards of business principles and ethics, including your right to privacy. Under no circumstances will we disclose any of your personal information to a third party, unless your specific permission is given. TRADE ASSOCIATIONS Australian and New Zealand Association of Antiquarian Booksellers [ANZAAB] Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association [ABA(Int)] International League of Antiquarian Booksellers [ILAB] REFERENCES CITED Hubber & Smith: Patrick White: A Bibliography. Brian Hubber & Vivian Smith. Quiddlers Press/Oak Knoll Press, Melbourne & New Castle, DE., 2004 O'Brien: T. E. Lawrence: A Bibliography. Philip M. O'Brien. Oak Knoll Press, New Castle, DE, 2000 IMAGES Additional images of items are available on our website, or by request. Catalogue images are not to scale. Front cover illustration, item 153 Back cover illustration, item 162 SPECIAL NOTE To comply with current COVID-19 restrictions, our bookshop is temporarily closed to the public. -

Patrick White Isobel Exhibition Gallery 1 Entry/Prologuetrundle 13 April 2012–8July 2012

LARGE PRINT LABELS Selected transcriptions Please return after use EXHIBITION MAP 3 4 2 5 5 1 6 ENTRY Key DESIGNED SCALE DATE DWG. No LOCATION SUBJECT VISUAL RENDERING THE LIFE OF PATRICK WHITE ISOBEL EXHIBITION GALLERY 1 ENTRY/PROLOGUETRUNDLE 13 APRIL 2012–8JULY 2012 2 CHILDHOOD PLACES 3 TRAVELS 1930–1946 4 HOME AT ‘DOGWOODS’ 5 HOME AT MARTIN ROAD 6 THEATRE 1 Patrick White (1912–1990) Letter from Patrick White to Dr G. Chandler, Director General, National Library of Australia 1977 ink Manuscripts Collection National Library of Australia William Yang (b. 1943) Portrait of Patrick White, Kings Cross, New South Wales 1980 gelatin silver print Pictures Collection National Library of Australia 2 CHILDHOOD PLACES 2 General Register Office, London Certified copy of an entry of birth 28 November 1983 typeset ink Papers of Patrick White, 1930–2002 Manuscripts Collection National Library of Australia Hardy Brothers Ltd Eggcup and spoon given to Paddy as a christening gift 1910–1911, inscribed 1913 sterling silver Presented by Kerry Walker, February 2005 State Library of New South Wales 2 HEIR TO THE WHITE FAMILY HERITAGE The Whites were an established, wealthy grazing family in the Hunter region of New South Wales. At the time of his birth, White was heir to half the family property, ‘Belltrees’, in Scone. On returning to Australia from London in 1912, White’s parents decided to move to Sydney, as Ruth disliked the social scene in the Hunter and Dick had developed interests in horse racing that required him to spend more time in the city. Despite White’s brief association with the property, ‘Belltrees’ was one of many childhood landscapes that he recreated in his writing. -

The Well in the Shadow’, and This Meaning for The

Award-winning Australian author Chester Eagle journeys through Australian literature offering engaging essays on the works of writers including Miles Franklin, Patrick White, George Johnston, Beverley Farmer, Helen Garner and Alexis Wright. As Eagle says in his introduction: ‘The essays are not introductory. T I consider them rather as a sharing of one writer’s reflections with the thoughts of h e The Well in readers who are looking for something new to add to their thinking. What the fellow-writer has to offer is the insight that comes from having also been at the W heart of the risky business of creating and imagining. Writers can see what other ell ell writers are up to because they face the same problems and use the same tricks.’ the Shadow These entertaining essays are linked by the essential notion of what it means to be a writer in Australia, and as such offer up valuable insights into our literature i and country. n A Writer’s Journey through Australian Literature th e e sh adow Chester Eagle Chester Eagle Chester www.transitlounge.com.au Essay/Literary Criticism Ozlit Chester Eagle Books by Chester Eagle Hail & Farewell! An evocation of Gippsland (1971) Who could love the nightingale? (1974) Four faces, wobbly mirror (1976) At the window (1984) The garden gate (1984) Mapping the paddocks (1985) Play together, dark blue twenty (1986) House of trees (reissue of Hail & Farewell! 1987) Victoria Challis (1991) House of music (1996) Wainwrights’ mountain (1997) Waking into dream (1998) didgeridoo (1999) Janus (2001) The Centre & other -

The Vivisector Free Ebook

FREETHE VIVISECTOR EBOOK Patrick White,Professor of General Literature J M Coetzee | 617 pages | 27 Jan 2009 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780143105671 | English | New York, NY, United States Cannibalising The Artist: The Monster In Patrick White’s 'The Vivisector' The Vivisector The Vivisector the eighth published novel by Patrick White. Named for its sometimes The Vivisector analysis of Duffield and the major figures in his life, the book explores universal themes like the suffering of the artist, the need for truth The Vivisector the meaning of existence. The longest of White's novels, [1] The Vivisector was written in While the novel was dedicated The Vivisector painter Sidney NolanWhite The Vivisector any connection between Hurtle Duffield, the novel's central character, and Nolan or any other painter. I think it is one of White's great autobiography to be honest. Hurtle Duffield is born into a poor Australian family. They adopt him out to the wealthy Courtneys, who are seeking a companion for their hunchbacked daughter Rhoda. The precocious Hurtle gains artistic inspiration from the world that surrounds him, his adoptive mother, Maman, and Rhoda; the prostitute Nance, who is his first real love; the wealthy heiress Olivia Davenport; his Greek mistress Hero Pavloussi and finally the child prodigy Kathy The Vivisector. He becomes famous and his paintings are in great demand. However, he is unimpressed by the monetary and status gain this The Vivisector and continues to live a spartan life, beholden to nobody — even the Prime Minister. White's biographer, David Marrhas claimed that White The Vivisector being considered by a Nobel Prize committee to receive the Nobel Literature prize. -

The Criterion an International Journal in English

The Criterion www.the-criterion.com An International Journal in English ISSN 0976-8165 Vol. III. Issue. IV 1 December 2012 The Criterion www.the-criterion.com An International Journal in English ISSN 0976-8165 Illumination of Elizabeth Hunter: A Study of Patrick White’s The Eye of the Storm Mrs. B.Siva Priya Assistant Professor of English The Standard Fireworks Rajaratnam College for Women, Sivakasi- 626123 Virudhunagar District Tamil Nadu, INDIA Patrick White (May 28, 1912- September 30, 1990) was an Australian author who is widely regarded as one of the greatest novelists of the twentieth century. He is the first Australian to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature. His mature works include two poetry collections- Thirteen Poems (1930- under the pseudonym Patrick Victor Martindale) and The Ploughman and Other Poems (1935), thirteen novels, three short story collections- The Burnt Ones (1964), The Cockatoos (1974) and Three Uneasy Pieces (1987), four plays- Return to Abyssinia (1947), Four Plays (1965), Big Toys (1978) and Signal Driver (1983) and three non-fictions an autobiography, Flaws in the Glass (1981), Patrick White Speaks (1990) and Letters (ed. David Marr, 1994). His thirteen novels are Happy Valley (1939), The Living and the Dead (1948), The Aunt’s Story (1948), The Tree of Man (1955), Voss (1957), Riders in the Chariot (1961), The Solid Mandala (1966), The Vivisector (1970), The Eye of the Storm (1973), A Fringe of Leaves (1976), The Twyborn Affair (1979), Memoirs of Many in One (1986) and his thirteenth novel The Hanging Garden (2012) was left unfinished and published posthumously.