The Well in the Shadow’, and This Meaning for The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Юридическо Списание На НБУ, 2016–2017 Година, Брой 1–3 Law Journal of NBU, 2016–2017, No

Юридическо списание на НБУ, 2016–2017 година, брой 1–3 Law Journal of NBU, 2016–2017, No. 1–3 ОБЩЕСТВО НА НАРОДИТЕ И ОРГАНИЗАЦИЯ НА ОБЕДИНЕНИТЕ НАЦИИ – СРАВНИТЕЛЕН АНАЛИЗ НА ПРАВНАТА УРЕДБА КАТЕРИНА ЙОЧЕВА* „Никой не желае ООН да последва съдбата на Обществото на народите, което се проваля, защото не може да оказва реално влияние“. Владимир Путин1 Въведение Първите международни организации, преследващи общи цели, възникват едва през ХХ век. Идеи за създаването на такива организации обаче съществуват още преди това. Политическото разединение и враждите между отделните държави са основна причина за сравнително късното им осъществяване. Първи стъпки към осъществяването на тези идеи се правят през ХІХ век. Първоначално държавите създават международни организации, за да сътрудничат помежду си по отделни въпроси. Така през 1865 г. е създаден Международният телекомуникационен съюз като Международен телеграфен съюз, а девет години по-късно (1874 г.) и Световният пощенски съюз (сега и двата специализирани организации/агенции на ООН). Тези две събития дават надежда, че и големи световни проблеми могат да бъдат разрешени по пътя на взаимното съгласие. Идеята за предотвратяването на последиците от военните сблъсъци и изграждането на структура, която да се грижи за опазването на мира, постепенно започва да си проправя път. През 1899 г. в Хага се провежда първата Международна конференция за мира, която цели да разработи начини за разрешаване на кризи по мирен път, предотвратявайки войни, и систематизиране на правила за водене на война. Впоследствие е създаден Постоянният арбитражен съд, който започва да действа през 1902 г. Ужасът на Първата световна война (1914–1918 г.) предизвиква вземането на по- крайни мерки като създаването на Обществото на народите (ОН) на Парижката мирна 1 Президент на Руската федерация в изявление от 11.9.2013 г. -

The Architecture of International Organizations 1922-•1952

Leiden Journal of International Law (2021), 34, pp. 1–22 doi:10.1017/S092215652000059X ORIGINAL ARTICLE INTERNATIONAL LEGAL THEORY Designing for international law: The architecture of international organizations 1922–1952 Miriam Bak McKenna* Lund University, Faculty of Law, Lilla Gråbrödersgatan 4, 222 22 Lund, Sweden Email: [email protected] Abstract Situating itself in current debates over the international legal archive, this article delves into the material and conceptual implications of architecture for international law. To do so I trace the architectural devel- opments of international law’s organizational and administrative spaces during the early to mid twentieth century. These architectural endeavours unfolded in three main stages: the years 1922–1926, during which the International Labour Organization (ILO) building, the first building exclusively designed for an inter- national organization was constructed; the years 1927–1937 which saw the great polemic between mod- ernist and classical architects over the building of the Palace of Nations; and the years 1947–1952, with the triumph of modernism, represented by the UN Headquarters in New York. These events provide an illu- minating allegorical insight into the physical manifestation, modes of self-expression, and transformation of international law during this era, particularly the relationship between international law and the func- tion and role of international organizations. Keywords: architecture; historiography; international law; law and aesthetics; legal materiality 1. Introduction ‘When we make a building for the UN’, noted Oscar Niemeyer in 1947, we must have in mind what is the UN? It is an organization to set the nations of the world in a common direction and gives to the world security. -

Use of Theses

THESES SIS/LIBRARY TELEPHONE: +61 2 6125 4631 R.G. MENZIES LIBRARY BUILDING NO:2 FACSIMILE: +61 2 6125 4063 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY EMAIL: [email protected] CANBERRA ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA USE OF THESES This copy is supplied for purposes of private study and research only. Passages from the thesis may not be copied or closely paraphrased without the written consent of the author. FINDING A PLACE: LANDSCAPE AND THE SEARCH FOR IDENTITY IN THE EARLY NOVELS OF PATRICK WHITE Y asue Arimitsu A thesis submitted for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS at the Australian National University December 1985 11 Except where acknowledgement is made, this thesis is my own work. Yasue Arimitsu Ill ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Acknowledgements are due to many people, without whose assistance this work would have proved more difficult. These include Dr Livio Dobrez and Dr Susan McKer nan, whose patience was unfailing; Dr Bob Brissenden, who provided initial encourage ment; Mr Graham Cullum, for advice and assistance; Professor Ian Donaldson, for his valuable comments; and Jean Marshall, for her kind and practical support. Special thanks must be given to the typist, Norma Chin, who has worked hard and efficiently, despite many pressures. My gratitude is also extended to my many fellow post-graduates, who over the years have sustained, helped and inspired me. These in clude especially Loretta Ravera Chion, Anne Hopkins, David Jans, Andrew Kulerncka, Ann McCulloch, Robert Merchant, Julia Robinson, Leonie Rutherford and Terry Wat- son. Lastly I would like to thank the Australia-Japan Foundation, whose generous financial support made this work possible and whose unending concern and warmth proved most encouraging indeed. -

Books at 2016 05 05 for Website.Xlsx

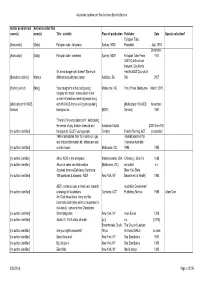

Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives Book Collection Author or editor last Author or editor first name(s) name(s) Title : sub-title Place of publication Publisher Date Special collection? Fallopian Tube [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : fallopiana Sydney, NSW Pamphlet July, 1974 December, [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : madness Sydney, NSW Fallopian Tube Press 1974 GLBTIQ with cancer Network, Gay Men's It's a real bugger isn't it dear? Stories of Health (AIDS Council of [Beresford (editor)] Marcus different sexuality and cancer Adelaide, SA SA) 2007 [Hutton] (editor) [Marg] Your daughter's at the door [poetry] Melbourne, VIC Panic Press, Melbourne March, 1975 Inequity and hope : a discussion of the current information needs of people living [Multicultural HIV/AIDS with HIV/AIDS from non-English speaking [Multicultural HIV/AIDS November, Service] backgrounds [NSW] Service] 1997 "There's 2 in every classroom" : Addressing the needs of gay, lesbian, bisexual and Australian Capital [2001 from 100 [no author identified] transgender (GLBT) young people Territory Family Planning, ACT yr calendar] 1995 International Year for Tolerance : gay International Year for and lesbian information kit : milestones and Tolerance Australia [no author identified] current issues Melbourne, VIC 1995 1995 [no author identified] About AIDS in the workplace Massachusetts, USA Channing L Bete Co 1988 [no author identified] Abuse in same sex relationships [Melbourne, VIC] not stated n.d. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome : [New York State [no author identified] 100 questions & answers : AIDS New York, NY Department of Health] 1985 AIDS : a time to care, a time to act, towards Australian Government [no author identified] a strategy for Australians Canberra, ACT Publishing Service 1988 Adam Carr And God bless Uncle Harry and his roommate Jack (who we're not supposed to talk about) : cartoons from Christopher [no author identified] Street Magazine New York, NY Avon Books 1978 [no author identified] Apollo 75 : Pix & story, all male [s.l.] s.n. -

Sov Presence in the UN Secretariat May 1985.P65

99th Congress COMMITTEE PRINT S. Prt. lst Session 99-52 SOVIET PRESENCE IN THE U.N. SECRETARIAT REPORT OF THE SENATE SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE UNITED STATES SENATE MAY 1985 Printed for the use of the Select Committee on Intelligence U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 47-800 O WASHINGTON: 1985 SENATE SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE [Established by S. Res. 400, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.] DAVE DURENBERGER, Minnesota, Chairman PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont, Vice Chairman WILLIAM V. ROTH, JR., Delaware LLOYD BENTSEN, Texas WILLIAM S. COHEN, Maine SAM NUNN, Georgia ORRIN HATCH, Utah THOMAS F. EAGLETON, Missouri FRANK MURKOWSKI, Alaska ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DAVID L. BOREN, Oklahoma CHIC HECHT, Nevada BILL BRADLEY, New Jersey MITCH McCONNELL, Kentucky ROBERT DOLE, Kansas, Ex Officio ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, Ex Officio BERNARD F. MCMAHON, Staff.Director ERIC D. NEWSOM, Minority Staff Director DORTHEA ROBERSON, Clerk (II) SOVIET PRESENCE IN THE UN SECRETARIAT1 SUMMARY The Soviet Union is effectively using the UN Secretariat in the conduct of its foreign relations, and the West is paying for most of it. The 800 Soviets assigned to the United Nations as international civil servants report directly to the Soviet missions and are part of an -organization managed by the Soviet Foreign Ministry, intelligence services, and the Central Committee of the Communist Party. The Soviets have gained significant advantage over the West through their compre- hensive approach to the strategy and tactics of, personnel placement and their detailed plans for using the United Nations to achieve Soviet foreign policy and intelligence objectives. Soviet and Eastern Bloc personnel use their positions to promote a broad range of foreign policy objectives in the United Nations and its specialized agencies. -

Education As a Driver to Integral Growth and Peace

THE CARITAS IN VERITATE FOUNDATION WORKING PAPERS “The City of God in the Palace of Nations” Education as a Driver to Integral Growth and Peace Ethical Reflections on the Right to Education With a selection of recent documents on the Church’s engagement on education www.fciv.org Edited by Alice de La Rochefoucauld and Dr. Carlo Maria Marenghi Electronic document preparation by Margarete Hahnen Published by FCIV 16 chemin du Vengeron, CH-1292 Chambésy © e Caritas in Veritate Foundation ISBN: 978-2-8399-2781-9 Dr. Quentin Wodon, Lead Economist, World Bank, and Distinguished Research Affi liate, 1 Kellogg Institute, University of Notre Dame Alice de La Rochefoucauld, Director, Caritas in Veritate Foundation Dr. Carlo Maria Marenghi, PhD, Adjunct Professor, Webster University, Geneva 17 Attaché, Permanent Observer Mission of the Holy See to the United Nations in Geneva Giorgia Corno, Research Fellow, Permanent Mission of the Holy See to the United Nations in Geneva SECTION ONE: EDUCATION AS A DRIVER TO INTEGRAL GROWTH 23 AND PEACE Chapter 1: Education and the International Legal Framework 25 United Nations Legal Framework 1. e Child’s Right to Education in International Human Rights Law: the Convention on the Rights of the Child Benyam Dawit Mezmur, Member of the United Nations Committee on 27 the Rights of the Child, Associate Professor of Law, University of the Western Cape, Member of the Ponti cal Commission for the Protection of Minors 2. e Right to Education in the roes of Globalization: Recontextualizing UNESCO Ana María Vega Gutiérrez, Professor of Law, Director of the UNESCO 41 Chair for Democratic Citizenship and Cultural Freedom, University of La Rioja Regional Frameworks 47 1. -

MSF and the War in the Former Yugoslavia 1991-2003 in the Former MSF and the War Personalities in Political and Military Positions at the Time of the Events

MSF AND THE WAR IN THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA 1991 - 2003 This case study is also available on speakingout.msf.org/en/msf-and-the-war-in-the-former-yugoslavia P MSF SPEAKS OUT MSF Speaking Out Case Studies In the same collection, “MSF Speaking Out”: - “Salvadoran refugee camps in Honduras 1988” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [October 2003 - April 2004 - December 2013] - “Genocide of Rwandan Tutsis 1994” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [October 2003 - April 2004 - April 2014] - “Rwandan refugee camps Zaire and Tanzania 1994-1995” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [October 2003 - April 2004 - April 2014] - “The violence of the new Rwandan regime 1994-1995” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [October 2003 - April 2004 - April 2014] - “Hunting and killings of Rwandan Refugee in Zaire-Congo 1996-1997” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [August 2004 - April 2014] - ‘’Famine and forced relocations in Ethiopia 1984-1986” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [January 2005 - November 2013] - “Violence against Kosovar Albanians, NATO’s Intervention 1998-1999” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [September 2006] - “War crimes and politics of terror in Chechnya 1994-2004’” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [June 2010-September 2014] - “Somalia 1991-1993: Civil war, famine alert and UN ‘military-humanitarian’ intervention” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [October 2013] - “MSF and North Korea 1995-1998” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [November 2014] - “MSF and Srebrenica 1993-2003” -

GWI UPDATE – 11 July 2018 — Graduate Women International

GWI UPDATE – 11 July 2018 GWI marks World Youth Skills Day and recognises that #SkillsChangeLives for women and girls around the world — — Graduate Women International News Open-Mindedness and Traditions: Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (EMRIP) inaugurates their 11th session The start of the 11th session of the EMRIP took place 9 July at the Palace of Nations, Geneva. On behalf of its members Graduate Women International (GWI) participated in the opening ceremony where Indigenous people from all around the world united in the Human Rights and Civilization Alliance Chamber to celebrate their ancestors, their culture and to begin the discussion of this year’s theme of free, prior and informed consent aimed toward the achievement of the Universal Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). In preparing for this session, EMRIP drew information from a broad variety of stakeholders and sources including: States, Indigenous peoples, civil society, academics, the Special Rapporteurs on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples; Universal Periodic Review; United Nations and other multilateral actors. Throughout EMRIP participants will explore new partnerships based on human rights, mutual respect and tolerance for the views of each other. The session outcomes will be submitted to the Human Rights Council at its thirty-ninth session (September 2018). The session was opened with a ceremony and prayer given in Mohawk, an Iroquoian language spoken by the Mohawk people, a native community located in the north east of United States and south east of Canada, which was followed by an English translation. Mr. Howard Thomson, the Indigenous speaker opening the session, expressed that his intention was to encourage open-mindedness and he expressed gratitude to mother earth, who provides us life and resources and to the forces of nature, who veil for the creatures of mother earth by giving them warmth and light. -

History of International Relations

3 neler öğrendik? bölüm özeti History of International Relations Editors Dr. Volkan ŞEYŞANE Evan P. PHEIFFER Authors Asst.Prof. Dr. Murat DEMİREL Dr. Umut YUKARUÇ CHAPTER 1 Prof.Dr. Burak Samih GÜLBOY Caner KUR CHAPTER 2, 3 Asst.Prof.Dr. Seçkin Barış GÜLMEZ CHAPTER 4 Assoc.Prof.Dr. Pınar ŞENIŞIK ÖZDABAK CHAPTER 5 Asst.Prof.Dr. İlhan SAĞSEN Res.Asst. Ali BERKUL Evan P. PHEIFFER CHAPTER 6 Dr. Çağla MAVRUK CAVLAK CHAPTER 7 Prof. Dr. Lerna K. YANIK Dr. Volkan ŞEYŞANE CHAPTER 8 T.C. ANADOLU UNIVERSITY PUBLICATION NO: 3920 OPEN EDUCATION FACULTY PUBLICATION NO: 2715 Copyright © 2019 by Anadolu University All rights reserved. This publication is designed and produced based on “Distance Teaching” techniques. No part of this book may be reproduced or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means of mechanical, electronic, photocopy, magnetic tape, or otherwise, without the written permission of Anadolu University. Instructional Designer Lecturer Orkun Şen Graphic and Cover Design Prof.Dr. Halit Turgay Ünalan Proof Reading Lecturer Gökhan Öztürk Assessment Editor Lecturer Sıdıka Şen Gürbüz Graphic Designers Gülşah Karabulut Typesetting and Composition Halil Kaya Dilek Özbek Gül Kaya Murat Tambova Beyhan Demircioğlu Handan Atman Kader Abpak Arul HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS E-ISBN 978-975-06-3603-5 All rights reserved to Anadolu University. Eskişehir, Republic of Turkey, October 2019 3328-0-0-0-1909-V01 Contents The Emergence The International of the Modern System During CHAPTER 1 CHAPTER 2 th International the Long 19 System Century Introduction ................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................. 29 History of the State System: From The Revolutions and the International System . -

Oliver BAKRESKI UDK: 355.45-049.6(494) Original Research Paper

Oliver BAKRESKI UDK: 355.45-049.6(494) Original research paper NATIONAL SECURITY POLICY IN SWITZERLAND Abstract The national security policy of Switzerland is based upon the specifics of the Swiss country and it is distinguished with great complicacy and complexity. Hence, the examination of the security policy should be founded of its complete comprehen- sion and thorough perception of the conditions in order to avoid improvisation and partiality. This signifies that the security policy should be rationally founded and to synthetize the efforts of all of the security actors in order to provide the necessary le- vel of security, for the society, the nation, and for the citizens. Generally, the altered nature of security threats conditioned the need for redefining the security policy of Switzerland and also imposed for adoption of new approaches toward security. Ac- cepting such reality, Switzerland has to adjust to the new circumstances for the pro- tection of the national interests and the neutrality policy. The Adaptation of the se- curity system in the new security environment has to be a reflection and result of the evident general overall inclusion of all the subjects, which are authorized for en- forcing the security policy. Keywords: SWITZERLAND, SECURITY, SECURITY POLICY, NATIONAL SECURITY, SE- CURITY SYSTEM 1. Introductory remarks Switzerland is a multinational, multilingual, religiously and economi- cally complex community, and it is consisted of four main lingual and cultu- ral domains: German, French, Italian and Romans (Radosavljević, 2011, 102). Even though most of the citizens speak German, the Swiss national identity pulls its roots from a common historical background, sharing the values such as federalism and direct democracy as well as Alpine symbolism. -

Chronology of Political Events in the Republic of Croatia July-December 1992

152 Chronology of Political Events in the Republic of Croatia July-December 1992 4.7. Arbitration Commission of the Conference on Yugoslavia, chaired by Robert Badinter, pronounces Declaration on Yugoslavia proclaiming that SFR Yugoslavia no lon.ger exists. 8.7. Before the summit meeting of the Conference on Security and Cooperation mn Europe in Helsinki, President Franjo Tudman of Croatia signs the Concluding Act of the Conference and othe.r documents, making Croatia an official member of the CSCE. 8.7. During the CSCE meeting in Helsinki, Presidenr Franjo Tudman of Croatia meetS Alija lzetbegoviC, President of the Presidency of Bosnia-Hercegovina. After their meeting a Joint Statement is issued rellecting the present relations between the two republics and offeri:ng possibilities for solving questions in dispure. 12.7. President Franjo Tudman of Croatia sends a letter to UN Secretary Genenl Boutros Ghali, President of the European Coll1lllission Jacques Delors, Secretary Gener:al of NATO Manfred Womer and many prominent world statesman calling for urgent and energetic international military intervention against the Serbian and Monetengriin aggressor. 16.7. A meeting is held in Za,greb between President Franjo Tudman of Croatia and British Foreign Secreuuy and Chainnan of the Ministerial Council of the EC Douglas Hurd. 18.7. M a meeting of the heads of goW!IMlents or fore1gn ininisters of the Central European Initiative in V'Jerulll, the Republk of Croatia is a~pted into fuU membe.rsb:lp of this regional organit.ation of Danubian and Adriatic counaies. 21.7. After talks in Zagreb between delegations of the Republic of Bosnia-Hercegovina and the Republic of Croatia, President Franjo Tudman of Croaria and the President of the Presidency of Bosnia-Hercegovinn Alija lzetbegovic sign th~ Agreement on Friendship and Cooperation between the Republic of Bosnia-Herc:egovilla and the Republic of Croaria. -

Patrick White: Twyborn Moments of Grace

Patrick White: Twyborn Moments of Grace By the end of the 1970s it was clear that critics were deeply divided over the nature of Patrick White's work and his achievement. At that time, I attempted to identify their fundamental differences by asking whether White was to be seen as a traditional novelist with a religious or theosophical view of life, or as a sophisticated, ironical modern mistrustful of language and sceptical of ever being able to express what might lie beyond words?1 Since then, literary criticism has registered some changes, and shocks. Indeed that term, 'literary criticism', has come to suggest the kind, or kinds, of exegesis and evaluation that prevailed in the ages that preceded our own brave new theoretical world. (I speak in general terms but have contemporary Australian academia specifically in mind.) How, I wonder, would a new reader, one coming to White for the first time through his most recent novel, The Twyborn Affair (1979), perceive him? In imagining this 'new' reader I have in mind a younger generation, particularly of students, who need not have encountered White's earlier novels and criticisms of them, and for whom the terms and concerns of Anglo-American New Criticism which affected the academic reception of White's work from at least the 1960s on are likely to be less immediate than those of Continental and North American theorists who have been influential during the last decade or more; for instance, Mikhail Bakhtin, who looms large on the program for this conference and in the October 1984 issue of PMI.A.