Patrick White Isobel Exhibition Gallery 1 Entry/Prologuetrundle 13 April 2012–8July 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Painting from One of the World's Greatest Collectors Offered

Press Release For Immediate Release Melbourne 3 May 2016 John Keats 03 9508 9900 [email protected] Australian Painting from One of the World’s Greatest Collectors Offered for Auction Important Australian & International Art | Auction in Sydney 11 May 2016 Roy de Maistre 1894-1968, The Studio Table 1928. Estimate $60,000-80,000 A painting from the collection of one of world’s most renowned art collectors and patrons will be auctioned by Sotheby’s Australia on 11 May at the InterContinental Sydney. Roy de Maistre’s The Studio Table 1928 was owned by Samuel Courtauld founder of The Courtauld Institute of Art and The Courtauld Gallery, and donor of acquisition funds for the Tate, London and National Gallery, London. De Maistre was one of Australia’s early pioneers of modern art and The Studio Table (estimate $60,000-80,000, lot 127, pictured) provides a unique insight into the studio environment of one of Anglo-Australia’s greatest artists. 1 | Sotheby’s Australia is a trade mark used under licence from Sotheby's. Second East Auction Holdings Pty Ltd is independent of the Sotheby's Group. The Sotheby's Group is not responsible for the acts or omissions of Second East Auction Holdings Pty Ltd Geoffrey Smith, Chairman of Sotheby’s Australia commented: ‘Sotheby’s Australia is honoured to be entrusted with this significant painting by Roy de Maistre from The Samuel Courtauld Collection. De Maistre’s works are complex in origins and intricate in construction. Mentor to the young Francis Bacon, De Maistre remains one of Australia’s most influential and enigmatic artists, whose unique contribution to the development of modern art in Australia and Great Britain is still to be fully understood and appreciated.’ A leading exponent of Modernism and Abstraction in Australia, The Studio Table was the highlight of Roy de Maistre’s solo exhibition in Sydney in 1928. -

UNIVERSITÀ CA‟ FOSCARI VENEZIA Department of Linguistics and Comparative Cultural Studies Dipartimento Di Studi Linguistici E Culturali Comparati

UNIVERSITÀ CA‟ FOSCARI VENEZIA Department of Linguistics and Comparative Cultural Studies Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Culturali Comparati Master‟s Degree in Language Sciences Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Scienze del Linguaggio Curriculum: Computational Linguistics Curriculum: Linguistica Computazionale Academic year | Anno accademico 2015/2016 ANNOTATING PATRICK WHITE‟S “THE SOLID MANDALA” WITH DEEP FEATURES TO UNRAVEL STYLISTIC DEVICES Candidate | Candidata Giulia MARCHESINI 855573 Supervisor: Prof. Rodolfo DELMONTE Co-supervisors: Dr. Gordon COLLIER Prof. Pia MASIERO TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapter One: Patrick White and The Solid Mandala 3 1.1 Patrick White, Australian writer 3 1.2 The settings in White‟s fiction: ordinary and extraordinary 7 1.3 Characters and themes in The Solid Mandala and other novels 8 1.4 The philosophy behind the themes 17 1.5 Realism, symbolism, modernism, and existential pessimism 20 Chapter Two: A unique style 23 2.1 Introduction to a stylistic analysis 23 2.2 Looking for a definition 24 2.3 Style, characters, narrative mode 26 2.4 Aspects of the analysis 30 2.5 From style to narratology 37 2.6 Measuring a style 39 Chapter Three: Criteria of annotation 41 3.1 From the annotation to the analysis 41 3.2 An introduction to markup languages 44 3.3 Annotation of The Solid Mandala 47 3.3.1 Considerations on the text 47 3.3.2 Internal subdivision in narremes 49 3.3.3 Annotation process 61 3.3.4 Annotation system 63 Chapter Four: Final analysis 106 4.1 Data and preparation 106 4.2 Protagonists and significant traits 115 4.3 A narratological approach: traits and events 122 4.4 A narratological approach: traits and relationships 130 Conclusions 135 Bibliography INTRODUCTION Nobel Prize winner Patrick White (1912-1990) is considered to be one of the greatest and most influential writers of the 20th century, not only in Australia, his country, but in the rest of the world, as well. -

Patrick White and God

Patrick White and God Patrick White and God By Michael Giffin Patrick White and God By Michael Giffin This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Michael Giffin All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-1750-3 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-1750-9 DEDICATED TO Benedict XVI logos philosopher and Patrick White mythos poet CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................... ix Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Continental Australian ........................................................................... 1 Historicized Rhetorician ........................................................................ 7 Perspectivist Disclosures ..................................................................... 10 Romantic Performances ....................................................................... 13 Interconnected Relationships ............................................................... 15 Chapter One .............................................................................................. -

Research Scholar an International Refereed E-Journal of Literary Explorations

ISSN 2320 – 6101 Research Scholar www.researchscholar.co.in An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations TREATMENT OF SEX AND ECCENTRICITY IN MAN-WOMAN RELATIONSHIP IN THE SELECTED WORKS OF PATRICK WHITE Dr. P. Bagavathy Rajan Assistant Professor of English Dept. of Information Technology Dr. Mahalingam College of Engineering and Technology Pollachi 642003, India ABSTRACT Patrick Whitehas had written 12 novels, two short-story collections and eight plays. Although he was popularly known as a novelist, the theatre was his first love. He started his career with the writing of revues. An important characteristic feature in the works of Patrick White is the eccentricity in man-woman relationship and the treatment of sex. It is natural for a writer to infuse certain traits of his own, while creating a character. He had created many women characters on the model of his mother.The eccentricity and abnormality in the treatment of sex and man- woman relationship in Patrick White’s work and the main reason for that could be traced in the biography of Patrick White. Key Words: Sex, Man-woman relationship, eccentricity, biographical approach Patrick White is one of the most eminent novelists, who brought laurels to the Australian literature by winning the Nobel Prize in the year 1973. He was awarded "for an epic and psychological narrative art which has introduced a new continent into literature". Patrick Victor Martindale White was born in the year 1912. He has written 12 novels, two short-story collections and eight plays. Although he was popularly known as a novelist, the theatre was his first love. -

Viewed English Journal Vol

Literary Horizon An International Peer-Reviewed English Journal Vol. 1, Issue 1 www.literaryhorizon.com February, 2021 Fictional Narratives on Patrick White with Special Reference to The Vivisector Miss Akanksha Tiwari Assistant Professor, Gyan Ganga Institute of Engineering and Technology, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India. Abstract: The research paper ―Fictional narratives of Patrick White‖ with special reference to The Vivisector contains a brief description of fictional and factual narratives, an introduction and analysis of some major works done by Patrick White and on the basis of that analysis his major themes were also discussed. His life and experiences and the major themes of his writings is briefly presented. The writing style, characters, plot and settings are some essential tools for every writer that is why it becomes mandatory to be discussed with reference to his major works. Special reference is given to his eighth novel The Vivisector (1970) because of many reasons and one of those reason is the protagonist of this novel ‗Hurtle Duffield‘ who is a painter but not an ordinary painter but a painter with an exceptional ability to look into the reality of a person. This character presents the conception of an artist, also he was a megalomaniac certainly and a Luciferian hero. He is a reflection of White‘s own personality and their life and experiences are so close to each other that it looks like we are reading Whites autobiography. This paper is a humble attempt to describe Whites major themes, his personality and his ideas Contact No. +91-8331807351 Page 63 Email: [email protected] Literary Horizon An International Peer-Reviewed English Journal Vol. -

Illustrator Draftsman 3&2

NONRESIDENT TRAINING COURSE August 1999 Illustrator Draftsman 3&2 Volume 2—Standard Drafting Practices and Theory NAVEDTRA 14276 DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Although the words “he,” “him,” and “his” are used sparingly in this course to enhance communication, they are not intended to be gender driven or to affront or discriminate against anyone. DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. PREFACE By enrolling in this self-study course, you have demonstrated a desire to improve yourself and the Navy. Remember, however, this self-study course is only one part of the total Navy training program. Practical experience, schools, selected reading, and your desire to succeed are also necessary to successfully round out a fully meaningful training program. COURSE OVERVIEW: In completing this nonresident training course, you will demonstrate a knowledge of the subject matter by correctly answering questions on the following subjects: composition, geometric construction, general drafting practices, technical drawings, perspective projections, and parallel projections. THE COURSE: This self-study course is organized into subject matter areas, each containing learning objectives to help you determine what you should learn along with text and illustrations to help you understand the information. The subject matter reflects day-to-day requirements and experiences of personnel in the rating or skill area. It also reflects guidance provided by Enlisted Community Managers (ECMs) and other senior personnel, technical references, instructions, etc., and either the occupational or naval standards, which are listed in the Manual of Navy Enlisted Manpower Personnel Classifications and Occupational Standards, NAVPERS 18068. THE QUESTIONS: The questions that appear in this course are designed to help you understand the material in the text. -

Important Australian and Aboriginal

IMPORTANT AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ART including The Hobbs Collection and The Croft Zemaitis Collection Wednesday 20 June 2018 Sydney INSIDE FRONT COVER IMPORTANT AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ART including the Collection of the Late Michael Hobbs OAM the Collection of Bonita Croft and the Late Gene Zemaitis Wednesday 20 June 6:00pm NCJWA Hall, Sydney MELBOURNE VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION Tasma Terrace Online bidding will be available Merryn Schriever OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION 6 Parliament Place, for the auction. For further Director PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE East Melbourne VIC 3002 information please visit: +61 (0) 414 846 493 mob IS NO REFERENCE IN THIS www.bonhams.com [email protected] CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL Friday 1 – Sunday 3 June CONDITION OF ANY LOT. 10am – 5pm All bidders are advised to Alex Clark INTENDING BIDDERS MUST read the important information Australian and International Art SATISFY THEMSELVES AS SYDNEY VIEWING on the following pages relating Specialist TO THE CONDITION OF ANY NCJWA Hall to bidding, payment, collection, +61 (0) 413 283 326 mob LOT AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 111 Queen Street and storage of any purchases. [email protected] 14 OF THE NOTICE TO Woollahra NSW 2025 BIDDERS CONTAINED AT THE IMPORTANT INFORMATION Francesca Cavazzini END OF THIS CATALOGUE. Friday 14 – Tuesday 19 June The United States Government Aboriginal and International Art 10am – 5pm has banned the import of ivory Art Specialist As a courtesy to intending into the USA. Lots containing +61 (0) 416 022 822 mob bidders, Bonhams will provide a SALE NUMBER ivory are indicated by the symbol francesca.cavazzini@bonhams. -

A STUDY GUIDE by Katy Marriner

© ATOM 2012 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN 978-1-74295-267-3 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Raising the Curtain is a three-part television series celebrating the history of Australian theatre. ANDREW SAW, DIRECTOR ANDREW UPTON Commissioned by Studio, the series tells the story of how Australia has entertained and been entertained. From the entrepreneurial risk-takers that brought the first Australian plays to life, to the struggle to define an Australian voice on the worldwide stage, Raising the Curtain is an in-depth exploration of all that has JULIA PETERS, EXECUTIVE PRODUCER ALINE JACQUES, SERIES PRODUCER made Australian theatre what it is today. students undertaking Drama, English, » NEIL ARMFIELD is a director of Curriculum links History, Media and Theatre Studies. theatre, film and opera. He was appointed an Officer of the Order Studying theatre history and current In completing the tasks, students will of Australia for service to the arts, trends, allows students to engage have demonstrated the ability to: nationally and internationally, as a with theatre culture and develop an - discuss the historical, social and director of theatre, opera and film, appreciation for theatre as an art form. cultural significance of Australian and as a promoter of innovative Raising the Curtain offers students theatre; Australian productions including an opportunity to study: the nature, - observe, experience and write Australian Indigenous drama. diversity and characteristics of theatre about Australian theatre in an » MICHELLE ARROW is a historian, as an art form; how a country’s theatre analytical, critical and reflective writer, teacher and television pre- reflects and shape a sense of na- manner; senter. -

Use of Theses

THESES SIS/LIBRARY TELEPHONE: +61 2 6125 4631 R.G. MENZIES LIBRARY BUILDING NO:2 FACSIMILE: +61 2 6125 4063 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY EMAIL: [email protected] CANBERRA ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA USE OF THESES This copy is supplied for purposes of private study and research only. Passages from the thesis may not be copied or closely paraphrased without the written consent of the author. FINDING A PLACE: LANDSCAPE AND THE SEARCH FOR IDENTITY IN THE EARLY NOVELS OF PATRICK WHITE Y asue Arimitsu A thesis submitted for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS at the Australian National University December 1985 11 Except where acknowledgement is made, this thesis is my own work. Yasue Arimitsu Ill ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Acknowledgements are due to many people, without whose assistance this work would have proved more difficult. These include Dr Livio Dobrez and Dr Susan McKer nan, whose patience was unfailing; Dr Bob Brissenden, who provided initial encourage ment; Mr Graham Cullum, for advice and assistance; Professor Ian Donaldson, for his valuable comments; and Jean Marshall, for her kind and practical support. Special thanks must be given to the typist, Norma Chin, who has worked hard and efficiently, despite many pressures. My gratitude is also extended to my many fellow post-graduates, who over the years have sustained, helped and inspired me. These in clude especially Loretta Ravera Chion, Anne Hopkins, David Jans, Andrew Kulerncka, Ann McCulloch, Robert Merchant, Julia Robinson, Leonie Rutherford and Terry Wat- son. Lastly I would like to thank the Australia-Japan Foundation, whose generous financial support made this work possible and whose unending concern and warmth proved most encouraging indeed. -

Patrick White

Bibliothèque Nobel 1973 Bernhard Zweifel Patrick White Year of Birth 1912 Year of Death 1990 Language Englisch Award for an epic and psychological narrative art Justification: which has introduced a new continent into literature Supplemental Information Secondary Literature • I. Björksten, Partick White: A General Introduction (1976) • Carolyn Jane Bliss, Patrick White's Fiction (1986) • David J. Tacey, Patrick White: Fiction and the Unconscious (1988) • Laurence Steven, Dissociation and Wholeness in Patrick White's Fiction (1989) • Rodney S tenning Edgecombe, Vision and Style in Patrick White (1989) • Peter Wolfe (ed.), Critical Essays on Patrick White (1990) • David Marr , Patrick White: A Life (1992) • Michael Giffin, Patrick White and the Religious Imagination (1999) • John Colmer, Patrick White (1984) • John C olmer, Patrick White's Riders in the Chariot (1978) • Simon During, Patrick White (1996) • Karin Hansson, The Warped Universe: A Study of Im agery and Structure in Seven Novels by Patrick White (1984) • Brian Kiernan, Patrick White (1980) • Patricia A.Morley, The Mystery of U nity: Theme and technique in the novels of Patrick White (1972) Works Catalogue Drama 1950 - 1959 The Tree of Man [1955] 173.1550 1930 - 1939 Voss [1957] 173.1570 The School for Friends [1935] Bread and Butter Women [1935] 1960 - 1969 Riders in the Chariot [1961] 173.1610 1940 - 1949 Being Kind to Titina [1962] 173.1640 After Alep [1945] Willy-Wagtails by Moonlight [1962] 173.1640 Return to Abyssinia [1947] The Letters [1964] 173.1640 The Ham Funeral [1947] -

Books at 2016 05 05 for Website.Xlsx

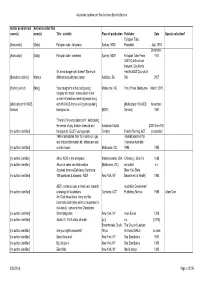

Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives Book Collection Author or editor last Author or editor first name(s) name(s) Title : sub-title Place of publication Publisher Date Special collection? Fallopian Tube [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : fallopiana Sydney, NSW Pamphlet July, 1974 December, [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : madness Sydney, NSW Fallopian Tube Press 1974 GLBTIQ with cancer Network, Gay Men's It's a real bugger isn't it dear? Stories of Health (AIDS Council of [Beresford (editor)] Marcus different sexuality and cancer Adelaide, SA SA) 2007 [Hutton] (editor) [Marg] Your daughter's at the door [poetry] Melbourne, VIC Panic Press, Melbourne March, 1975 Inequity and hope : a discussion of the current information needs of people living [Multicultural HIV/AIDS with HIV/AIDS from non-English speaking [Multicultural HIV/AIDS November, Service] backgrounds [NSW] Service] 1997 "There's 2 in every classroom" : Addressing the needs of gay, lesbian, bisexual and Australian Capital [2001 from 100 [no author identified] transgender (GLBT) young people Territory Family Planning, ACT yr calendar] 1995 International Year for Tolerance : gay International Year for and lesbian information kit : milestones and Tolerance Australia [no author identified] current issues Melbourne, VIC 1995 1995 [no author identified] About AIDS in the workplace Massachusetts, USA Channing L Bete Co 1988 [no author identified] Abuse in same sex relationships [Melbourne, VIC] not stated n.d. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome : [New York State [no author identified] 100 questions & answers : AIDS New York, NY Department of Health] 1985 AIDS : a time to care, a time to act, towards Australian Government [no author identified] a strategy for Australians Canberra, ACT Publishing Service 1988 Adam Carr And God bless Uncle Harry and his roommate Jack (who we're not supposed to talk about) : cartoons from Christopher [no author identified] Street Magazine New York, NY Avon Books 1978 [no author identified] Apollo 75 : Pix & story, all male [s.l.] s.n. -

THE VISION of ALIENATION an Analytical Approach to the Works of Patrick White Through the First Four Novels by WILLIAM GERALD SC

THE VISION OF ALIENATION An analytical approach to the works of Patrick White through the first four novels by WILLIAM GERALD SCHERMBRUCKER B.A., University of Cape Town, 1957 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts in the Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May, 1966 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall, make it freely available for reference and -. study, I further agree that permission., for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives'. It is understood that copying of - publication of this thesis for. financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission', . Department of..^^ The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada 17th August, 1966. Date ii ABSTRACT This study of Patrick White's work is chiefly concerned with the first four novels, but refers also to some poetry, the short stories, the plays and the three later novels. It traces the development of themes and techniques in these four novels in terms of artistic vision and the rendering of that vision. The early, experimental works, up to The Living and the Dead are treated at considerable length, chiefly to show how the later developments are basically improve• ments and variations on the themes and techniques which have already been used. A second reason for the length of this part of the treatment is that, in the existing criticism of White, these early works are almost entirely ignored.