Creating Communities Towards a Description of the Mask-Function in Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patrick White and God

Patrick White and God Patrick White and God By Michael Giffin Patrick White and God By Michael Giffin This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Michael Giffin All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-1750-3 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-1750-9 DEDICATED TO Benedict XVI logos philosopher and Patrick White mythos poet CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................... ix Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Continental Australian ........................................................................... 1 Historicized Rhetorician ........................................................................ 7 Perspectivist Disclosures ..................................................................... 10 Romantic Performances ....................................................................... 13 Interconnected Relationships ............................................................... 15 Chapter One .............................................................................................. -

Viewed English Journal Vol

Literary Horizon An International Peer-Reviewed English Journal Vol. 1, Issue 1 www.literaryhorizon.com February, 2021 Fictional Narratives on Patrick White with Special Reference to The Vivisector Miss Akanksha Tiwari Assistant Professor, Gyan Ganga Institute of Engineering and Technology, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India. Abstract: The research paper ―Fictional narratives of Patrick White‖ with special reference to The Vivisector contains a brief description of fictional and factual narratives, an introduction and analysis of some major works done by Patrick White and on the basis of that analysis his major themes were also discussed. His life and experiences and the major themes of his writings is briefly presented. The writing style, characters, plot and settings are some essential tools for every writer that is why it becomes mandatory to be discussed with reference to his major works. Special reference is given to his eighth novel The Vivisector (1970) because of many reasons and one of those reason is the protagonist of this novel ‗Hurtle Duffield‘ who is a painter but not an ordinary painter but a painter with an exceptional ability to look into the reality of a person. This character presents the conception of an artist, also he was a megalomaniac certainly and a Luciferian hero. He is a reflection of White‘s own personality and their life and experiences are so close to each other that it looks like we are reading Whites autobiography. This paper is a humble attempt to describe Whites major themes, his personality and his ideas Contact No. +91-8331807351 Page 63 Email: [email protected] Literary Horizon An International Peer-Reviewed English Journal Vol. -

An Analysis of Food and Its Significance in the Australian Novels of Christina Stead, P

F.O.O.D. (Fighting Order Over Disorder): An Analysis of Food and Its Significance in the Australian Novels of Christina Stead, Patrick White and Thea Astley. Jane Frugtneit A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Humanities James Cook University August 2007 ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to find a correlation between food as symbol and food as necessity, as represented in selected Australian novels by Christina Stead, Patrick White and Thea Astley. Food as a springboard to a unique interpretation of the selected novels has been under-utilised in academic research. Although comparatively few novels were selected for study, on the basis of fastidiousness, they facilitated a rigorous hermeneutical approach to the interpretation of food and its inherent symbolism. The principle behind the selection of these novels lies in the complexity of the prose and how that complexity elicits the “transformative powers of food” (Muncaster 1996, 31). The thesis examines both the literal and metaphorical representations of food in the novels and relates how food is an inextricable part of ALL aspects of life, both actual and fictional. Food sustains, nourishes and, intellectually, its many components offer unique interpretative tools for textual analysis. Indeed, the overarching structure of the thesis is analogous with the processes of eating, digestion and defecation. For example, following a discussion of the inextricable link between food, quest and freedom in Chapter One, which uncovers contrary attitudes towards food in the novels discussed, the thesis presents a more complex psychoanalytic theory of mental disorders related to food in Chapter Two. -

THE LIFE of THINGS in the FICTION of PATRICK WHITE By

STILL LIFE: THE LIFE OF THINGS IN THE FICTION OF PATRICK WHITE By SUSAN JANE WHALEY M.A., University of Windsor, 1979 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA February 1987 ©Susan Jane Whaley In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of fiYltf] {)h The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 DE-6 (3/81) II ABSTRACT t "Still Life" argues that Patrick White's fiction reveals objects in surprising, unexpected attitudes so as to challenge the process by which the mind usually connects with the world around it. In particular, White's novels disrupt readers' tacit assumptions about the lethargic nature of substance; this thesis traces how his fiction reaches beyond familiar linguistic and stylistic forms in order to reinvent humanity's generally passive perception of reality. The first chapter outlines the historical context of ideas about the "object," tracing their development from the Bible through literary movements such as romanticism, symbolism, surrealism and modernism. -

Satire and Parody in the Novels of Patrick White

Contrivance, Artifice, and Art: Satire and Parody in the Novels of Patrick White James Harold Wells-Green 0 A thesis presented for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication, University of Canberra, June 2005 ABSTRACT This study arose out of what I saw as a gap in the criticism of Patrick White's fiction in which satire and its related subversive forms are largely overlooked. It consequently reads five of White's post-1948 novels from the standpoint of satire. It discusses the history and various theories of satire to develop an analytic framework appropriate to his satire and it conducts a comprehensive review of the critical literature to account for the development of the dominant orthodox religious approach to his fiction. It compares aspects of White's satire to aspects of the satire produced by some of the notable exemplars of the English and American traditions and it takes issue with a number of the readings produced by the religious and other established approaches to White's fiction. I initially establish White as a satirist by elaborating the social satire that emerges incidentally in The Tree of Man and rather more episodically in Voss. I investigate White's sources for Voss to shed light on the extent of his engagement with history, on his commitment to historical accuracy, and on the extent to which this is a serious high-minded historical work in which he seeks to teach us more about our selves, particularly about our history and identity. The way White expands his satire in Voss given that it is an eminently historical novel is instructive in terms of his purposes. -

Modern Australian Literature

Modern Australian Literature Catalogue 240 September 2020 TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE Unless otherwise described, all books are in the original cloth or board binding, and are in very good, or better, condition with defects, if any, fully described. Our prices are nett, and quoted in Australian dollars. Traditional trade terms apply. Items are offered subject to prior sale. All orders will be confirmed by email. PAYMENT OPTIONS We accept the major credit cards, PayPal, and direct deposit to the following account: Account name: Kay Craddock Antiquarian Bookseller Pty Ltd BSB: 083 004 Account number: 87497 8296 Should you wish to pay by cheque we may require the funds to be cleared before the items are sent. GUARANTEE As a member or affiliate of the associations listed below, we embrace the time-honoured traditions and courtesies of the book trade. We also uphold the highest standards of business principles and ethics, including your right to privacy. Under no circumstances will we disclose any of your personal information to a third party, unless your specific permission is given. TRADE ASSOCIATIONS Australian and New Zealand Association of Antiquarian Booksellers [ANZAAB] Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association [ABA(Int)] International League of Antiquarian Booksellers [ILAB] REFERENCES CITED Hubber & Smith: Patrick White: A Bibliography. Brian Hubber & Vivian Smith. Quiddlers Press/Oak Knoll Press, Melbourne & New Castle, DE., 2004 O'Brien: T. E. Lawrence: A Bibliography. Philip M. O'Brien. Oak Knoll Press, New Castle, DE, 2000 IMAGES Additional images of items are available on our website, or by request. Catalogue images are not to scale. Front cover illustration, item 153 Back cover illustration, item 162 SPECIAL NOTE To comply with current COVID-19 restrictions, our bookshop is temporarily closed to the public. -

Patrick White Isobel Exhibition Gallery 1 Entry/Prologuetrundle 13 April 2012–8July 2012

LARGE PRINT LABELS Selected transcriptions Please return after use EXHIBITION MAP 3 4 2 5 5 1 6 ENTRY Key DESIGNED SCALE DATE DWG. No LOCATION SUBJECT VISUAL RENDERING THE LIFE OF PATRICK WHITE ISOBEL EXHIBITION GALLERY 1 ENTRY/PROLOGUETRUNDLE 13 APRIL 2012–8JULY 2012 2 CHILDHOOD PLACES 3 TRAVELS 1930–1946 4 HOME AT ‘DOGWOODS’ 5 HOME AT MARTIN ROAD 6 THEATRE 1 Patrick White (1912–1990) Letter from Patrick White to Dr G. Chandler, Director General, National Library of Australia 1977 ink Manuscripts Collection National Library of Australia William Yang (b. 1943) Portrait of Patrick White, Kings Cross, New South Wales 1980 gelatin silver print Pictures Collection National Library of Australia 2 CHILDHOOD PLACES 2 General Register Office, London Certified copy of an entry of birth 28 November 1983 typeset ink Papers of Patrick White, 1930–2002 Manuscripts Collection National Library of Australia Hardy Brothers Ltd Eggcup and spoon given to Paddy as a christening gift 1910–1911, inscribed 1913 sterling silver Presented by Kerry Walker, February 2005 State Library of New South Wales 2 HEIR TO THE WHITE FAMILY HERITAGE The Whites were an established, wealthy grazing family in the Hunter region of New South Wales. At the time of his birth, White was heir to half the family property, ‘Belltrees’, in Scone. On returning to Australia from London in 1912, White’s parents decided to move to Sydney, as Ruth disliked the social scene in the Hunter and Dick had developed interests in horse racing that required him to spend more time in the city. Despite White’s brief association with the property, ‘Belltrees’ was one of many childhood landscapes that he recreated in his writing. -

Modern Books

Modern Books 119. Acosta (Oscar Zeta) . The Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo . Illustrations. Straight Arrow Books, San Francisco, 1972. First Edition. A little foxing at edges but a nice copy in slightly frayed dust-wrapper which is a little sunned at the spine panel; bookseller’s stamp on front pastedown. £80 120. Acosta (Oscar Zeta) . The Revolt of the Cockroach People . Illustrations. Straight Arrow Books, San Francisco, 1973. First Edition. Head and foot of spine a little bruised, otherwise a very nice copy in slightly frayed and chipped dust-wrapper which is somewhat browned at the spine panel; bookseller’s stamp on front pastedown. £65 121. Akimoto (Shunkichi) . The Lure of Japan . Frontispiece with tissue guard, plates, folding map. The Hokuseido Press, Tokyo, 1934. Revised Edition. Cloth a little marked and worn, upper hinge cracked, illustrated end-papers somewhat browned and a little foxing, else a nice copy, uncut (a few leaves clumsily opened); bookseller’s stamp on front pastedown, publisher’s slip giving European and American prices tipped-in at end. £20 122. Aldiss (Brian W.) . A Soldier Erect, or, Further Adventures of the Hand-Reared Boy . Weidenfeld and Nicolson, [1971]. First Edition. Slight crease to spine, somewhat spotted at edges, but a nice copy in dust-wrapper which has a few small pieces missing at the corners. £30 123. Algren (Nelson) . The Man with the Golden Arm . Double Day & Company Inc., Garden City, New York, 1949. First Edition. Cloth with a little foxing and soiling, upper hinge cracked, otherwise a nice copy in slightly chipped, frayed and marked dust-wrapper. -

Harold Pinter /22/ (The Sir Joseph Gold Collection)

A MOSTLY MODERN AFFAIR one hundred pleasures (or so), for now Peter B. Howard Serendipity Books 1201 University Avenue Berkeley, CA 94702 voice: (510) 841-7455 fax: (510) 841-1920 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.serendipitybooks.com Terms 1) Any book may be returned for any reason. 2) California residents please add appropriate sales tax. Design & Layout by: Andrea Latham 558 33rd Street, Richmond, CA 94804 USA (510) 233-3144 I / 5 MANUSCRIPTS, ARCHIVES, AND UNCOMMON BOOKS IN ALL FIELDS C II / 17 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUTHOR AND SUBJECT COLLECTIONS III / 43 SETS IV / 49 AFRICAN-AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN LITERATURE V / 55 RUSSIAN LITERATURE IN RUSSIAN VI / 61 ART / FINE PRINTING / BOOK ARTS / ILLUSTRATION VII / 69 MODERN FICTION / PROSE VIII / 83 MODERN AMERICAN, BRITISH AND CANADIAN POETRY IX / 93 PHOTOGRAPHY X / 99 DETECTIVE AND SCIENCE FICTION XI / 103 SCREENPLAYS I MANUSCRIPTS, ARCHIVES, AND UNCOMMON BOOKS IN ALL FIELDS / 5 Theophilus Siegfried Bauer /1/ MUSEUM SINICUM. [ca 1730]. Manuscript, folio, imperial Russia, two volumes and index in one binding. On Dutch “J. Honig Zoonen” paper [the paper on which was written the American Declaration of Independence]. Manuscript of the first book on the Chinese language to be published in the West. I: (12) + 73 + (3) + 84; II: (2) + 130 + 104 (including 51 holograph plates of Chinese characters); (101) pp. A full description has been prepared. Hitherto unrecorded. $45,000.00 /2/ Charles Bonnet (1720-1793) OEUVRES D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE ET DE PHILOSOPHIE. Neuchatel: Samuel Fauche, 1779-1783. 18 volumes, complete. 8vo. In original wrappers. $2750.00 postpaid 6 / Jocelyn Brooke /3/ THE WILD ORCHIDS OF BRITAIN [1948-1950]. -

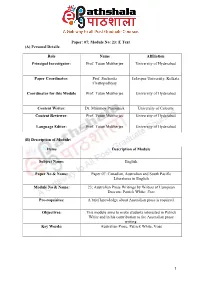

Paper: 07; Module No: 23: E Text (A) Personal Details: Role Name

Paper: 07; Module No: 23: E Text (A) Personal Details: Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee University of Hyderabad Paper Coordinator: Prof. Suchorita Jadavpur University, Kolkata Chattopadhyay Coordinator for this Module Prof. Tutun Mukherjee University of Hyderabad Content Writer: Dr. Mrinmoy Pramanick University of Calcutta Content Reviewer: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee University of Hyderabad Language Editor: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee University of Hyderabad (B) Description of Module: Items Description of Module Subject Name: English Paper No & Name: Paper 07: Canadian, Australian and South Pacific Literatures in English Module No & Name: 23; Australian Prose Writings by Writers of European Descent: Patrick White: Voss Pre-requisites: A brief knowledge about Australian prose is required. Objectives: This module aims to make students interested in Patrick White and in his contribution to the Australian prose writing. Key Words: Australian Prose, Patrick White, Voss 1 About the Module This module gives glimpses of Australian prose tradition and it situates Patrick White in the context of it. Module talks very briefly about bio-note of Patrick White and his contribution to Australian prose and his achievements. After that module talks about major works by Patrick White and discusses especially on Voss. Later reception of White in the literary world beyond Australia is discussed and a brief critical appreciation is presented here. At the end of the module you will find conclusion and a summary of the whole discussion. Students are suggested to consult the reference and further reading list to have wider conception about the writer in particular and Australian prose tradition in general. Introduction If we see the history of literature of Australia and New Zealand we can find a collective values in spite of all the differences and conflicts. -

[ Eritagevollection

[ ERITAGEV OLLECTION N ELSON M EERS F OUNDATION ECCF STATE LIBRARY OF NEW SOUTH WALES [ ERITAGEV OLLECTION N ELSON M EERS F OUNDATION ECCF STATE LIBRARY OF NEW SOUTH WALES A free exhibition from 25 January to 31 December 2003 State Library of New South Wales Macquarie Street, Sydney, NSW 2000 Telephone (02) 9273 1414 Facsimile (02) 9273 1255 TTY (02) 9273 1541 Email [email protected] www.sl.nsw.gov.au Exhibition opening hours: 9 am to 5 pm weekdays, 11 am to 5 pm weekends and selected public holidays Gallery space created by Jon Hawley Project Manager: Rosemary Moon Coordinating Curator: Louise Anemaat Curators: Paul Brunton, Alan Davies, Elizabeth Ellis, Cheryl Evans, Warwick Hirst, Jennifer O’Callaghan, Maggie Patton, Stephen Martin and Richard Neville Editors: Helen Cumming, Theresa Willsteed Graphic Designer: Simon Leong Photographer: Scott Wajon Printer: Penfold Buscombe Paper: Spicers Impress Matt 300 gsm and 130 gsm Print run: 20,000 P&D-0941-1/2003 ISBN 0 7313 7124 0 © State Library of New South Wales, January 2003 Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders of exhibited and published material. We apologise if, through inability to trace owners, material has been included for which permission has not been specifically sought. If you believe you are the copyright holder of material published in this guide, please contact the Library's Intellectual Property and Copyright section. For further information on the Heritage Collection, please see www.sl.nsw.gov.au/heritage/ Note: This guide lists all items that will be on display at various times throughout 2003. -

The Criterion an International Journal in English

The Criterion www.the-criterion.com An International Journal in English ISSN 0976-8165 Vol. III. Issue. IV 1 December 2012 The Criterion www.the-criterion.com An International Journal in English ISSN 0976-8165 Illumination of Elizabeth Hunter: A Study of Patrick White’s The Eye of the Storm Mrs. B.Siva Priya Assistant Professor of English The Standard Fireworks Rajaratnam College for Women, Sivakasi- 626123 Virudhunagar District Tamil Nadu, INDIA Patrick White (May 28, 1912- September 30, 1990) was an Australian author who is widely regarded as one of the greatest novelists of the twentieth century. He is the first Australian to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature. His mature works include two poetry collections- Thirteen Poems (1930- under the pseudonym Patrick Victor Martindale) and The Ploughman and Other Poems (1935), thirteen novels, three short story collections- The Burnt Ones (1964), The Cockatoos (1974) and Three Uneasy Pieces (1987), four plays- Return to Abyssinia (1947), Four Plays (1965), Big Toys (1978) and Signal Driver (1983) and three non-fictions an autobiography, Flaws in the Glass (1981), Patrick White Speaks (1990) and Letters (ed. David Marr, 1994). His thirteen novels are Happy Valley (1939), The Living and the Dead (1948), The Aunt’s Story (1948), The Tree of Man (1955), Voss (1957), Riders in the Chariot (1961), The Solid Mandala (1966), The Vivisector (1970), The Eye of the Storm (1973), A Fringe of Leaves (1976), The Twyborn Affair (1979), Memoirs of Many in One (1986) and his thirteenth novel The Hanging Garden (2012) was left unfinished and published posthumously.