Mexico's Indigenous Communities and Self-Defense Forces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9. LISTA CANDIDATURAS RSP.Xlsx

INSTITUTO ELECTORAL Y DE PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO LISTA DE CANDIDATURAS DE AYUNTAMIENTOS REDES SOCIALES PROGRESISTAS NO. MUNICIPIO PARTIDO NOMBRECARGO GÉNERO 1 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP PATRICIA MANZANO RESENDIZ PRESIDENCIA MUNICIPAL PROPIETARIA MUJER 2 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP ELIZABETH MALDONADO RAMIREZ PRESIDENCIA MUNICIPAL SUPLENTE MUJER 3 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP CARLOS IGNACIO GARCIA VALVERDE SINDICATURA 1 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 4 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP JOSE LUIS ZAMORA NOLASCO SINDICATURA 1 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 5 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP BEATRIZ CORTES CHAVARRIA SINDICATURA 2 PROPIETARIA MUJER 6 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP MELANI VARGAS RUIZ SINDICATURA 2 SUPLENTE MUJER 7 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP VICENTE AVILA ORTIZ REGIDURIA 1 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 8 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP SERGIO VALVERDE ORTIZ REGIDURIA 1 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 9 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP KARLA YANETH NAVA TAPIA REGIDURIA 2 PROPIETARIA MUJER 10 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP YULIETH GOMEZ MAYO REGIDURIA 2 SUPLENTE MUJER 11 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP OLIVER ALEXIS ALCOCER MANZANO REGIDURIA 3 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 12 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP EDUARDO GONZALEZ TERESA REGIDURIA 3 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 13 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP KATHYA ALEJANDRA MAYORGA RAMIREZ REGIDURIA 4 PROPIETARIA MUJER 14 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP SARAI ABIGAIL GARCIA DE DIOS REGIDURIA 4 SUPLENTE MUJER 15 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP MOISES ARMANDO VALLE PAREDES REGIDURIA 5 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 16 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP DAVID LOPEZ LOZANO REGIDURIA 5 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 17 ATOYAC DE ÁLVAREZ RSP BERNARDO NERI BENITEZ PRESIDENCIA MUNICIPAL PROPIETARIO -

Directorio De Oficialías Del Registro Civil

DIRECTORIO DE OFICIALÍAS DEL REGISTRO CIVIL DATOS DE UBICACIÓN Y CONTACTO ESTATUS DE FUNCIONAMIENTO POR EMERGENCIA COVID19 CLAVE DE CONSEC. MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD NOMBRE DE OFICIALÍA NOMBRE DE OFICIAL En caso de ABIERTA o PARCIAL OFICIALÍA DIRECCIÓN HORARIO TELÉFONO (S) DE CONTACTO CORREO (S) ELECTRÓNICO ABIERTA PARCIAL CERRADA Días de atención Horarios de atención 1 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ ACAPULCO 1 ACAPULCO 09:00-15:00 SI CERRADA CERRADA LUNES, MIÉRCOLES Y LUNES-MIERCOLES Y VIERNES 9:00-3:00 2 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ TEXCA 2 TEXCA FLORI GARCIA LOZANO CONOCIDO (COMISARIA MUNICIPAL) 09:00-15:00 CELULAR: 74 42 67 33 25 [email protected] SI VIERNES. MARTES Y JUEVES 10:00- MARTES Y JUEVES 02:00 OFICINA: 01 744 43 153 25 TELEFONO: 3 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ HUAMUCHITOS 3 HUAMUCHITOS C. ROBERTO LORENZO JACINTO. CONOCIDO 09:00-15:00 SI LUNES A DOMINGO 09:00-05:00 01 744 43 1 17 84. CALLE: INDEPENDENCIA S/N, COL. CENTRO, KILOMETRO CELULAR: 74 45 05 52 52 TELEFONO: 01 4 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ KILOMETRO 30 4 KILOMETRO 30 LIC. ROSA MARTHA OSORIO TORRES. 09:00-15:00 [email protected] SI LUNES A DOMINGO 09:00-04:00 TREINTA 744 44 2 00 75 CELULAR: 74 41 35 71 39. TELEFONO: 5 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ PUERTO MARQUEZ 5 PUERTO MARQUEZ LIC. SELENE SALINAS PEREZ. AV. MIGUEL ALEMAN, S/N. 09:00-15:00 01 744 43 3 76 53 COMISARIA: 74 41 35 [email protected] SI LUNES A DOMINGO 09:00-02:00 71 39. 6 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ PLAN DE LOS AMATES 6 PLAN DE LOS AMATES C. -

La Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR)

Resultados de la convocatoria del Programa ProÁrbol de la Comisión Nacional Forestal 2012: La Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR) a través de la Gerencia Estatal Guerrero y el Gobierno del Estado de Guerrero, con fundamento en los artículos 11, 15 y 27 de las Reglas de Operación del Programa ProÁrbol 2012 de la Comisión Nacional Forestal, publicado en el Diario Oficial de la Federación el 21 de diciembre de 2011; da a conocer el resultado de las solicitudes ASIGNADAS para 2012, según acuerdo del Comité Técnico del Estado de Guerrero, en la sesión de fecha 22 de Marzo de 2012. Asimismo se da a conocer el calendario de capacitación sobre derechos y obligaciones de los beneficiarios de dicho programa: Solicitantes con recursos ASIGNADOS Superficie ó Unidad de Concepto de apoyo No. Folio Solicitud Solicitante Folio del apoyo Nombre del predio Municipio cantidad medida Monto asignado a/ asignada (especificar) B1.4 COSERVACIÓN 1 S201212001503 EJIDO IGUALITA Y RESTAURACIÓN BCS201212000230 EL PALMAR XALPATLÁHUAC 60 HAS. $174,000.00 DE SUELOS BIENES COMUNALES DE SAN B1.4 COSERVACIÓN 2 S201212001563 MIGUEL CHIEPETLAN Y SUS Y RESTAURACIÓN BCS201212000236 LOMA DE POCITO TLAPA DE COMONFORT 60 HAS. $174,000.00 ANEXOS DE SUELOS B1.4 COSERVACIÓN 3 S201212000933 EJIDO CUBA Y RESTAURACIÓN BCS201212000132 EL RANCHO XALPATLÁHUAC 60 HAS. $174,000.00 DE SUELOS B1.4 COSERVACIÓN BIENES COMUNALES DE TONALAPA 4 S201212001389 Y RESTAURACIÓN BCS201212000212 TLAPA DE COMONFORT 70 HAS. $203,000.00 ZACUALPAN TLALXOTALCO DE SUELOS B1.4 COSERVACIÓN 5 S201212001135 EJIDO CHIMALACACINGO Y RESTAURACIÓN BCS201212000178 LA SIDRA COPALILLO 60 HAS. $174,000.00 DE SUELOS B1.4 COSERVACIÓN BIENES COMUNALES DE 6 S201212001769 Y RESTAURACIÓN BCS201212000269 ZAPOTE BLANCO TLAPA DE COMONFORT 80 HAS. -

Migración En Tierra Caliente: Una Perspectiva Sobre Tlatlaya

Migración en tierra caliente: una perspectiva sobre Tlatlaya Adhir Hipólito Álvarez INTRODUCCIÓN EL NIVEL DE IMPORTANCIA QUE SE BRINDA a cada investigación tiene mucho que ver con el objeto de estudio, para este caso se considera que la cul- tura evidencia la identidad individual y colectiva en cualquier grupo social, es decir, que la estructura de una sociedad en particular posee manifestaciones de subjetividad individual y colectiva. Bajo este supuesto teórico, el trabajo presenta los resultados de una investigación etnográfica llevada a cabo en la municipalidad de Tlatlaya, Estado de México, particularmente en la comunidad de Río Topilar. Se parte de un análisis de los cambios asociados a la dimensión cultural de la migración transnacional en su espacio comunitario, es decir, donde acontece la experiencia de los sujetos migrantes. Para ello, aquí asumimos que cada tipo de migración social de forma documentada o indocumentada impone peculiaridades propias a los casos de estudio. Entonces, es pertinente señalar que dada la gran cantidad de población expulsada, el impacto social y el problema huma- no manifestado en los diversos grados de estructuración social y cultural que genera la migración de un país a otro, constituye una justificación de los estudios culturales de la migración. IDENTIDAD Y CULTURA MIGRANTE: MIGRACIÓN EN RÍO TOPILAR LA COMUNIDAD DE ESTUDIO, denominada Río Topilar, perteneciente al mu- nicipio de Tlatlaya, Estado de México cuenta con 125 pobladores según 255 Conapo (2005), y prácticamente la mitad de las personas se encuentran residiendo en Estados Unidos, tanto hombres como mujeres; es decir, un aproximado de 63 personas que en su mayoría oscilan entre 20 y 40 años de edad, tiempo en el que el ser humano suele ser mas productivo para el trabajo, y que, en lo individual y lo colectivo reconstruyen su es- pacio vital y de cotidianidad en términos de su cultura e identidad. -

Geologic and Geochronologic Data from the Guerrero Terrane in the Tejupilco Area, Southern Mexico: New Constraints on Its Tectonic Interpretation

Journal of South American Earth Sciences 13 (2000) 355±375 www.elsevier.nl/locate/jsames Geologic and geochronologic data from the Guerrero terrane in the Tejupilco area, southern Mexico: new constraints on its tectonic interpretation M. ElõÂas-Herrera*, J.L. SaÂnchez-Zavala, C. Macias-Romo Instituto de GeologõÂa, Universidad Nacional AutoÂnoma de MeÂxico, Ciudad Universitaria, DelegacioÂn CoyoacaÂn, Mexico DF 04510, Mexico Abstract The eastern part of the Guerrero terrane contains two tectonically juxtaposed metavolcanic-sedimentary sequences with island arc af®nities: the lower, Tejupilco metamorphic suite, is intensely deformed with greenschist facies metamorphism; the upper, Arcelia-Palmar Chico group, is mildly to moderately deformed with prehnite-pumpellyite facies metamorphism. A U±Pb zircon age of 186 Ma for the Tizapa metagranite, and Pb/Pb isotopic model ages of 227 and 188 Ma for the conformable syngenetic Tizapa massive sul®de deposit, suggest a Late Triassic±Early Jurassic age for the Tejupilco metamorphic suite. 40Ar/39Ar and K±Ar age determinations of metamorphic minerals from different units of the Tejupilco metamorphic suite in the Tejupilco area date a local early Eocene thermal event related to the emplacement of the undeformed Temascaltepec granite. The regional metamorphism remains to be dated. 40Ar/39Ar ages of 103 and 93 Ma for submarine volcanics support an Albian±Cenomanian age for the Arcelia-Palmar Chico group, although it may extend to the Berriasian. U±Pb isotopic analyses of zircon from the Tizapa metagranite, together with Nd isotopic data, reveal inherited Precambrian zircon components within units of the Tejupilco metamorphic suite, precluding the generation of Tejupilco metamorphic suite magmas from mantle- or oceanic lithosphere-derived melts, as was previously considered to be the case. -

Modernización Del Camino: Tlapa - Marquelia, Tramo: Km

MIA REGIONAL MARQUELIA MANIFESTACION DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL MODALIDAD REGIONAL MODERNIZACION DEL CAMINO: TLAPA-MARQUELIA, TRAMO: KM. 68+000 AL KM. 72+000 EN EL ESTADO DE GUERRERO Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes Centro SCT Guerrero file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Captura/Escritorio/proteccion%20de%20Datos%20Meli/GRO/estudios/2003/12GE2003VD017.html (1 de 106) [23/11/2009 11:28:09 a.m.] MIA REGIONAL MARQUELIA I DATOS GENERALES DEL PROYECTO, DEL PROMOVENTE Y DEL RESPONSABLE DEL ESTUDIO DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL I.1 Datos generales del proyecto. 1. Clave del proyecto. _________________________ 2. Nombre del proyecto Modernización del Camino: Tlapa - Marquelia, Tramo: Km. 68+000 al Km. 72+000. 3. Datos del sector y tipo de proyecto 3.1 Sector Vías Generales de Comunicación 3.2 Subsector: Infraestructura carretera 3.3 Tipo de proyecto: Carreteras y autopistas (A1) 4. Estudio de riesgo y su modalidad En virtud de que no se van a realizar actividades consideradas como altamente riesgosas no aplica la presentación del estudio de riesgo. 5. Ubicación del proyecto 5.1. Calle y número, o bien nombre del lugar y/o rasgo geográfico de referencia, en caso de carecer de dirección postal Camino: Tlapa - Marquelia, Tramo: Km. 68+000 (poblado Paraje Montero) al Km. 72+000 (poblado file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Captura/Escritorio/proteccion%20de%20Datos%20Meli/GRO/estudios/2003/12GE2003VD017.html (2 de 106) [23/11/2009 11:28:09 a.m.] MIA REGIONAL MARQUELIA Tres Marías). 5.2. Código postal No aplica. 5.3. Entidad federativa Guerrero. 5.4. Municipio. Malinaltepec. 5.5. Localidad(es), Las comunidades que se localizan dentro del área del estudio son: Paraje Montero y Tres Marías. -

Entidad Municipio Localidad Long

Entidad Municipio Localidad Long Lat Guerrero Ahuacuotzingo ACATEYAHUALCO 990134 174604 Guerrero Ahuacuotzingo AJUATETLA 990428 174654 Guerrero Ahuacuotzingo CHINANTLA 990003 174711 Guerrero Ahuacuotzingo EL TERRERO 990055 174628 Guerrero Ahuacuotzingo LOS AMATES (LA POCHOTERA) 985614 174915 Guerrero Ahuacuotzingo MAZAPA 990204 174552 Guerrero Ahuacuotzingo MAZATLÁN 984637 174153 Guerrero Ahuacuotzingo MITLANCINGO 985853 174950 Guerrero Ahuacuotzingo RINCÓN DE COZAHUAPA 985658 174942 Guerrero Ahuacuotzingo SAN JUAN (LAS JOYAS) 990402 174915 Guerrero Ahuacuotzingo SANTA CATARINA (SANTA CATARINA LAS JOYAS) 990528 174500 Guerrero Ahuacuotzingo TEPETLATIPA 990129 174823 Guerrero Ahuacuotzingo TLAQUILCINGO 985512 175145 Guerrero Ahuacuotzingo TLAXINTLE MORADO 985532 175027 Guerrero Ahuacuotzingo TOTOLZINTLA 990114 174617 Guerrero Ahuacuotzingo VISTA HERMOSA TLAQUILCINGO 985519 175133 Guerrero Ajuchitlán del Progreso EL AGUAJE 1002132 181144 Guerrero Ajuchitlán del Progreso IXCAPUZALCO 1002254 181141 Guerrero Ajuchitlán del Progreso LAS CRUCES 1002331 181318 Guerrero Ajuchitlán del Progreso LAS JUNTAS (LAS JUNTAS DEL RÍO CHIQUITO) 1002230 181107 Guerrero Ajuchitlán del Progreso NANCHE COLORADO (EL NANCHE) 1002003 181316 Guerrero Ajuchitlán del Progreso SAN BARTOLO 1002301 181320 Guerrero Ajuchitlán del Progreso SAN PABLO ORIENTE 1002155 181027 Guerrero Ajuchitlán del Progreso SANTA ANA DEL ÁGUILA 1002349 181227 Guerrero Ajuchitlán del Progreso SANTA ROSA PRIMERA (SANTA ROSA ORIENTE) 1002330 181229 Guerrero Apaxtla CACALOTEPEC 1000032 180250 -

OK04487027 Doctorado 1.Pdf

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE GUERRERO UNIDAD DE CIENCIAS DE DESARROLLO REGIONAL DOCTORADO EN CIENCIAS AMBIENTALES 1ª. GENERACIÓN LAS TRANSFORMACIONES DE LA TRAZA URBANA EN MARQUELIA, GRO. POR EL CAMBIO DEL USO DEL SUELO Y EL IMPACTO EN LOS RECURSOS NATURALES. DIAGNÓSTICO PARA UN DESARROLLO TURÍSTICO SUSTENTABLE TESIS Que para obtener el grado de Doctor en Ciencias Ambientales P r e s e n t a: Arq. Urb. Ramón Solís Carmona Comité Tutoral: Dr. Justiniano González González Director de tesis Unidad de Ciencias de Desarrollo Regional, Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero Dra. Rocío López Velasco Unidad de Ciencias de Desarrollo Regional, Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero Dr. Sergio García Ibáñez Unidad Académica de Ecología Marina, Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero Dr. Jesús Castillo Aguirre Unidad Académica de Economía, Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero Dr. Rafael Flores Garza Unidad Académica de Ecología Marina, Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero Asesores de Tesis Acapulco de Juárez Guerrero, México, noviembre 18 de 2011 Ramón Solís Carmona Tesis Doctoral CONTENIDO TEMA PÁGINA INTRODUCCIÓN 2 I ANTECEDENTES 4 II JUSTIFICACION 25 III OBJETIVOS 28 IV PLANTEAMIENTO DEL PROBLEMA 28 V HIPÓTESIS 30 VI MÉTODOLOGÍA 31 VII RESULTADOS Y DISCUSIÓN 42 7.1 Cualidades per se desarrollo turístico 45 7.2 Políticas para el desarrollo del ecoturismo en Marquelia, Gro., y programas para el desarrollo de los espacios rurales y naturales 55 7.3 Centros de Interpretación de la Naturaleza y Observatorio de aves 66 7.4 Actividades recreativas activas 71 7.5 Diagnóstico 81 7.6 -

Proyección De Casillas Corte 30 De Septiembre De 2016

INSTITUTO ELECTORAL Y DE PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO DIRECCIÓN EJECUTIVA DE ORGANIZACIÓN Y CAPACITACIÓN ELECTORAL COORDINACIÓN DE ORGANIZACIÓN ELECTORAL Proyección con Lista Nominal de casillas básicas, contiguas, extraordinarias, y especiales por distrito y municipio con corte al 30 de septiembre de 2016. Total de Total por Casillas por Secciones sin Distrito Municipio Básicas Contiguas Extraordinarias Especiales secciones municipio distrito rango CHILPANCINGO DE LOS BRAVO 47 47 90 0 4 141 0 1 141 TOTAL: 47 47 90 0 4 141 0 CHILPANCINGO DE LOS BRAVO 57 57 96 3 1 157 0 2 157 TOTAL: 57 57 96 3 1 157 0 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 70 69 96 0 8 173 1 3 173 TOTAL: 70 69 96 0 8 173 1 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 79 79 83 0 4 166 0 4 166 TOTAL: 79 79 83 0 4 166 0 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 58 58 89 2 0 149 0 5 149 TOTAL: 58 58 89 2 0 149 0 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 53 53 82 0 1 136 0 6 136 TOTAL: 53 53 82 0 1 136 0 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 39 39 106 17 1 163 0 7 163 TOTAL: 39 39 106 17 1 163 0 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 21 21 30 0 1 52 0 8 COYUCA DE BENÍTEZ 60 59 36 3 1 99 151 1 TOTAL: 81 80 66 3 2 151 1 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 62 62 75 4 1 142 0 9 142 TOTAL: 62 62 75 4 1 142 0 TÉCPAN DE GALEANA 38 37 23 0 1 61 1 ATOYAC DE ÁLVAREZ 73 67 25 4 0 96 6 10 182 BENITO JUÁREZ 15 15 10 0 0 25 0 TOTAL: 126 119 58 4 1 182 7 ZIHUATANEJO DE AZUETA 26 26 40 1 1 68 0 PETATLÁN 56 53 21 0 0 74 3 11 181 TÉCPAN DE GALEANA 29 29 7 3 0 39 0 TOTAL: 111 108 68 4 1 181 3 ZIHUATANEJO DE AZUETA 39 38 50 4 3 95 1 COAHUAYUTLA 31 29 0 3 0 32 2 12 179 LA UNIÓN 33 33 11 8 0 52 0 TOTAL: 103 100 61 15 3 179 3 COORDINACIÓN DE ORGANIZACIÓN ELECTORAL 03:36 p. -

126 Tlapacholapa-Mochitlan.Pdf

SECRETARÍA DE GOBERNACIÓN COORDINACIÓN NACIONAL DE PROTECCIÓN CIVIL CENTRO NACIONAL DE PREVENCIÓN DE DESASTRES Octubre 16 de 2013 NOTA INFORMATIVA INESTABILIDAD DE LADERAS EN LA COMUNIDAD DE EL RINCÓN DE TLAPACHOLAPA, PERTENECIENTE AL MUNICIPIO DE MOCHITLÁN, ESTADO DE GUERRERO La presente nota se emite en atención a la solicitud de la Coordinación Nacional de Protección Civil y de la Subsecretaría de Protección Civil del estado de Guerrero, para que especialistas del Servicio Geológico Mexicano realizaran una visita técnica y valoración de los fenómenos de Inestabilidad de Laderas e inundaciones que se han suscitado en la comunidad de El Rincón de Tlapacholapa del municipio de Mochitlán, estado de Guerrero, como consecuencia de las lluvias intensas acaecidas en el territorio mexicano del 12 al 25 de septiembre, originadas por las Tormentas Tropicales Manuel e Ingrid, así como por los Frentes Fríos No. 1 y 2 de los últimos días. La cabecera municipal de Mochitlán pertenece a la Región Centro del estado, se localiza al oriente de Chilpancingo, entre las coordenadas geográficas 17°09´27” a 17°31´34” de latitud norte y 99°15´20” a 99°28´33” de longitud oeste, tiene una extensión territorial de 585 Km2, colinda con los municipios de Tixtla y Chilpancingo de los bravo al norte, al sur con Juan R. Escudero y Tecoanapa, al oriente con Quechultenango y Chilapa de Álvarez y al poniente con Chilpancingo de los Bravo, se encuentra a 20 Km en línea recta de la capital del estado, con una altitud de 1005 m.s.n.m., esta bañado por los rios El Salado, Zacapochapa, Huacapa, Chapolapa, Coaxtlahuacán, Zintlanapa y Tlapacholapa, Figura 1. -

GUERRERO SUPERFICIE 63 794 Km² POBLACIÓN 3 115 202 Hab

A MORELIA A PÁTZCUARO A ZITÁCUARO 99 km. A ZITÁCUARO 99 km A NAUCALPAN 67 km A ENT. CARR. 134 A C Villa Madero E F G I J K F.C. A K B D H 102°00' 282 km 30' A MORELIA 101°00' 30' 100°00' 30' 99°00' 30' APIZACO 50 km A APIZACO A CD. DE 10 km MÉXICO CIUDAD DE T MEX 35 km Y 15 F.C. A MÉXICO BUENAVISTA TLAXCALA 4 AL CENTRO 19 km 4 M L N MEX 32 15 1 C MEX 37 TOLUCA D GUERRERO SUPERFICIE 63 794 km² POBLACIÓN 3 115 202 hab. I S Á T A MEX R Ario de Rosales 51 I 76 F T E O 40 GUERRERO D Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes C 22 E Gabriel Zamora R 31 X. A ORIZABA 150 km 69 A L Dirección General de Planeación km 114 TEHUACÁN A X = 190 000 m Y = 2 118 000 m F.C. A TEHUACÁN A F.C. Esata carta fue coordinada y supervisada por la Subdirección de Cartografía de la A 33 GUERRERO (2008) Dirección de Estadística y Cartografía. MEX 3 Tenango de Arista 120 34 Para mayor información de la Infraestructura del Sector en el Estado diríjase al O Centro SCT ubicado en: Av. Dr. y Gral. Gabriel Leyva Alarcon s/n esq. 159 Nocupétaro O Av. Juventud; Col. Burócratas, C.P. 39090, Chilpancingo, Gro. 5 NUEVA ITALIA Temascaltepec DE RUIZ rancho 24 Punga MEX Río MEX 95 18 32 C 55 112 19 PUEBLA H 152 9 31 19°00' MEX 32 I 11 115 2 D 56 MEX 134 TENANCINGO DE DEGOLLADO 39 MEX X 34 115 M É 127 16 C 83 CUERNAVACA Presa Manuel Ávila Camacho Tiquicheo Río 5 33 5 ATLIXCO San San Miguel Jerónimo 50 33 42 Río MEX Mesa del Zacate TEMIXCO 1 190 Chiquito Eréndira El Cirián A MEX I 37 Pungarancho La Paislera Ixtapan de la Sal 3 MEX 60 Naranjo 95 La Playa Pácuaro El D CUAUTLA Los Tepehuajes Río M La Joya El Tule 18 Pinzán Gacho X = 568 000 m Y = 2 076 000 m El Ojo de Agua El Agua Buena Los Jazmines Los Guajes Arroyo Salado L. -

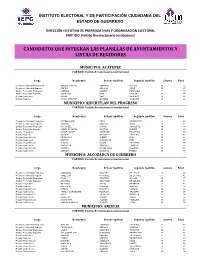

Ayuntamientos Pri.Pdf

INSTITUTO ELECTORAL Y DE PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO DIRECCIÓN EJECUTIVA DE PRERROGATIVAS Y ORGANIZACIÓN ELECTORAL PARTIDO: Partido Revolucionario Institucional CANDIDATOS QUE INTEGRAN LAS PLANILLAS DE AYUNTAMIENTOS Y LISTAS DE REGIDORES MUNICIPIO: ACATEPEC PARTIDO: Partido Revolucionario Institucional Cargo Nombre(s) Primer Apellido Segundo Apellido Género Edad Presidente Municipal Propietario SELENE CRISTAL SORIANO GARCIA M 35 Presidente Municipal Suplente RUFINA IGNACIO CRUZ M 27 Sindico Procurador Propietario LIBRADO GARCIA PASCUALA H 42 Sindico Procurador Suplente MAURICIO NERI GARCIA H 24 Regidor Propietario ESTER NERI BASURTO M 22 Regidor Suplente MARIA JENNIFER ORTUÑO SANCHEZ M 26 MUNICIPIO: AJUCHITLAN DEL PROGRESO PARTIDO: Partido Revolucionario Institucional Cargo Nombre(s) Primer Apellido Segundo Apellido Género Edad Presidente Municipal Propietario VICTOR HUGO VEGA HERNANDEZ H 45 Presidente Municipal Suplente RAMIRO ARAUJO NAVA H 37 Sindico Procurador Propietario MA. ISABEL CHAMU ANACLETO M 38 Sindico Procurador Suplente ANGELICA MARIA OLMEDO GOMEZ M 42 Regidor Propietario MIGUEL ANGEL CAMBRON FIGUEROA H 49 Regidor Suplente WILVERT MARTINEZ CATALAN H 45 Regidor Propietario (2) FRANCISCA JAIMEZ RIOS M 27 Regidor Suplente (2) BERTHA GUILLERMO PIÑA M 37 Regidor Propietario (3) ELICEO ROJAS VALENTIN H 25 Regidor Suplente (3) PERFECTO SANCHEZ LIMONES H 32 Regidor Propietario (4) JUSTINA MAYORAZGO HIGUERA M 42 Regidor Suplente (4) EUFEMIA BLANCAS PINEDA M 37 MUNICIPIO: ALCOZAUCA DE GUERRERO PARTIDO: Partido Revolucionario