Common Congenital Heart Disorders in Adults

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unusual Right Ventricle Aneurysm and Dysplastic Pulmonary Valve With

CASE REPORT Unusual right ventricle aneurysm and dysplastic pulmonary valve with mitral valve hypoplasia Ozge Pamukcu, Abdullah Ozyurt, Mustafa Argun, Ali Baykan, Nazmi Narın, Kazım Uzum Erciyes University School of Medicine, Division of Pediatric Cardiology, Kayseri, Turkey ABSTRACT We report a newborn with an unusual combination of aneurysmally dilated thin‑walled right ventricle with hypertrophy of the apical muscles of the right ventricle. There was narrow pulmonary annulus, pulmonary regurgitation, and hypoplasia of the mitral valve and left ventricle. We propose that this heart represents a partial form of Uhl`s anomaly. Keywords: Absent pulmonary valve, right ventricle aneurysm, Uhl’s anomaly INTRODUCTION A pansystolic murmur was heard. The chest X‑ray showed marked cardiomegaly and a cardiothoracic ratio of 85%. Aneursymal dilatation of the right ventricle can be seen Echocardiography showed an aneurysmally dilated right in several malformations like congenital aneurysm, Uhl’s ventricle [Figure 1, Videos 1‑3]. The entire right ventricle anomaly, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, except the apical portion was dilated. There was apical atrialized portion of the Ebstein’s anomaly, absent muscular hypertrophy of the right ventricle. [Figure 1] right pericardium, or post‑ischemic aneurysms.[1] Such The tricuspid valve was mildly hypoplastic (Z score ‑0.95) aneurysms are being increasingly diagnosed prenatally.[2] and prolapsing, but not displaced. The pulmonary valve was dysplastic and doming [Figure 2], with mild We report a case having an aneurysmatically dilated right pulmonary regurgitation [Figure 3]. Although the ventricle resembling the Uhl’s Anomaly, with an unusual pulmonary annulus was not very small, the anatomy combination of lesions. -

Essentials of Bedside Cardiology CONTEMPORARY CARDIOLOGY

Essentials of Bedside Cardiology CONTEMPORARY CARDIOLOGY CHRISTOPHER P. CANNON, MD SERIES EDITOR Aging, Heart Disease and Its Management: Facts and Controversies, edited by Niloo M. Edwards, MD, Mathew S. Maurer, MD, and Rachel B. Wellner, MD, 2003 Peripheral Arterial Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment, edited by Jay D. Coffman, MD, and Robert T. Eberhardt, MD, 2003 Essentials ofBedside Cardiology: With a Complete Course in Heart Sounds and Munnurs on CD, Second Edition, by Jules Constant, MD, 2003 Primary Angioplasty in Acute Myocardial Infarction, edited by James E. Tcheng, MD,2002 Cardiogenic Shock: Diagnosis and Treatment, edited by David Hasdai, MD, Peter B. Berger, MD, Alexander Battler, MD, and David R. Holmes, Jr., MD, 2002 Management of Cardiac Arrhythmias, edited by Leonard I. Ganz, MD, 2002 Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease, edited by Michael T. Johnstone and Aristidis Veves, MD, DSC, 2001 Blood Pressure Monitoring in Cardiovascular Medicine and Therapeutics, edited by William B. White, MD, 2001 Vascular Disease and Injury: Preclinical Research, edited by Daniell. Simon, MD, and Campbell Rogers, MD 2001 Preventive Cardiology: Strategies for the Prevention and Treatment of Coronary Artery Disease, edited by JoAnne Micale Foody, MD, 2001 Nitric Oxide and the Cardiovascular System, edited by Joseph Loscalzo, MD, phD and Joseph A. Vita, MD, 2000 Annotated Atlas of Electrocardiography: A Guide to Confident Interpretation, by Thomas M. Blake, MD, 1999 Platelet Glycoprotein lIb/IlIa Inhibitors in Cardiovascular Disease, edited by A. Michael Lincoff, MD, and Eric J. Topol, MD, 1999 Minimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery, edited by Mehmet C. Oz, MD and Daniel J. Goldstein, MD, 1999 Management ofAcute Coronary Syndromes, edited by Christopher P. -

Giant Right Atrium Or Ebstein Anomaly? Hacer Kamalı1, Abdullah Erdem1*, Cengiz Erol2 and Atıf Akçevin3

ISSN: 2378-2951 Kamalı et al. Int J Clin Cardiol 2017, 4:104 DOI: 10.23937/2378-2951/1410104 Volume 4 | Issue 4 International Journal of Open Access Clinical Cardiology CASE REPORT Giant Right Atrium or Ebstein Anomaly? Hacer Kamalı1, Abdullah Erdem1*, Cengiz Erol2 and Atıf Akçevin3 1Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Istanbul Medipol University, Turkey 2Department of Radiology, Istanbul Medipol University, Turkey 3Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Istanbul Medipol University, Turkey *Corresponding author: Abdullah Erdem, Associate Professor of Pediatric Cardiology, Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Istanbul Medipol University, Istanbul, Turkey, Tel: +905-0577-05805, Fax: +90212467064, E-mail: drabdullaherdem@ hotmail.com partment for exercise intolerance. She had been diag- Abstract nosed and followed up as Ebstein anomaly for ten years. Many acquired and congenital pathologies could cause en- Her heart rate was 75/min with normal jugular venous largement of Right Atrium (RA). In rare pathologies we couldn’t find an obvious reason for enlargement of RA. Sometimes it pressure. Findings of lung examination were normal. leads to misdiagnosis if we try to explain an unknown pa- Auscultation of heart revealed a 2/6 systolic murmur on thology with well known pathology. In this article we de- the lower left edge of the sternum. On abdominal ex- scribe a woman who presented with giant enlargement of amination, there was no organomegaly. Arterial Oxygen the RA misdiagnosed as Ebstein anomaly. Cardiac MRI is highly helpful for differential diagnosis of these kinds of atrial Saturation (SpO2) was 98%. Electrocardiography (ECG) pathologies. Although it is rare, giant RA should be consid- revealed absence of atrial fibrillation, the rhythm was ered in differential diagnosis of huge RA without an obvious sinus but there was right axis deviation and right bundle cause. -

Maternal and Fetal Outcomes of Admission for Delivery in Women with Congenital Heart Disease

Supplementary Online Content Hayward RM, Foster E, Tseng ZH. Maternal and fetal outcomes of admission for delivery in women with congenital heart disease. JAMA Cardiol. Published online April 12, 2017. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2017.0283 eTable 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria eTable 2. CHD Diagnoses With Corresponding ICD-9 Codes eTable 3. Outcomes eTable 4. Medical Comorbidities eTable 5. Type of CHD This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/01/2021 eTable 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria Inclusion Criteria ICD-9 Codes ICD-9 Procedure Codes DRG Codes 72[0-1], 7221, 7229, 7231, 7239, 724, 72[5- 370, 371, 372, 373, Delivery Admission* V27, 650 9], 7322, 7359, 736, 740, 741, 742, 744, 7499 374, 375 Cesarean Section 669.71 74.0X, 74.1X, 74.2X, 74.4X Exclusion Criteria Ectopic and Molar Pregnancy 63X Dilation and Curettage or Intra- 69.01, 69.51, 74.91, 75.0 amniotic injection for abortion X is any number 0-9. *From Kuklina EV et al. An enhanced method for identifying obstetric deliveries: implications for estimating maternal morbidity. Matern Child Health J. 2008. © 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/01/2021 eTable 2. CHD Diagnoses With Corresponding ICD-9 Codes Complex Congenital Heart Defects ICD-9 Codes Endocardial Cushion Defects 745.6 Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome 746.7 Tetralogy -

How to Recognize a Suspected Cardiac Defect in the Neonate

Neonatal Nursing Education Brief: How to Recognize a Suspected Cardiac Defect in the Neonate https://www.seattlechildrens.org/healthcare- professionals/education/continuing-medical-nursing-education/neonatal- nursing-education-briefs/ Cardiac defects are commonly seen and are the leading cause of death in the neonate. Prompt suspicion and recognition of congenital heart defects can improve outcomes. An ECHO is not needed to make a diagnosis. Cardiac defects, congenital heart defects, NICU, cardiac assessment How to Recognize a Suspected Cardiac Defect in the Neonate Purpose and Goal: CNEP # 2092 • Understand the signs of congenital heart defects in the neonate. • Learn to recognize and detect heart defects in the neonate. None of the planners, faculty or content specialists has any conflict of interest or will be presenting any off-label product use. This presentation has no commercial support or sponsorship, nor is it co-sponsored. Requirements for successful completion: • Successfully complete the post-test • Complete the evaluation form Date • December 2018 – December 2020 Learning Objectives • Describe the risk factors for congenital heart defects. • Describe the clinical features of suspected heart defects. • Identify 2 approaches for recognizing congenital heart defects. Introduction • Congenital heart defects may be seen at birth • They are the most common congenital defect • They are the leading cause of neonatal death • Many neonates present with symptoms at birth • Some may present after discharge • Early recognition of CHD -

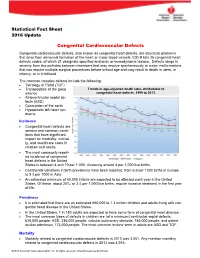

Congenital Cardiovascular Defects

Statistical Fact Sheet 2016 Update Congenital Cardiovascular Defects Congenital cardiovascular defects, also known as congenital heart defects, are structural problems that arise from abnormal formation of the heart or major blood vessels. ICD-9 lists 25 congenital heart defects codes, of which 21 designate specified anatomic or hemodynamic lesions. Defects range in severity from tiny pinholes between chambers that may resolve spontaneously to major malformations that can require multiple surgical procedures before school age and may result in death in utero, in infancy, or in childhood. The common complex defects include the following: Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) Transposition of the great Trends in age-adjusted death rates attributable to arteries congenital heart defects, 1999 to 2013. Atrioventricular septal de- fects (ASD) Coarctation of the aorta Hypoplastic left heart syn- drome Incidence Congenital heart defects are serious and common condi- tions that have significant impact on morbidity, mortali- ty, and healthcare costs in children and adults. The most commonly report- ed incidence of congenital heart defects in the United States is between 4 and 10 per 1,000, clustering around 8 per 1,000 live births. Continental variations in birth prevalence have been reported, from 6.9 per 1000 births in Europe to 9.3 per 1000 in Asia. An estimated minimum of 40,000 infants are expected to be affected each year in the United States. Of these, about 25%, or 2.4 per 1,000 live births, require invasive treatment in the first year of life. Prevalence It is estimated that there are an estimated 650,000 to 1.3 million children and adults living with con- genital heart disease in the United States. -

Systolic Murmurs

Murmurs and the Cardiac Physical Exam Carolyn A. Altman Texas Children’s Hospital Advanced Practice Provider Conference Houston, TX April 6 , 2018 The Cardiac Physical Exam Before applying a stethoscope….. Some pearls on • General appearance • Physical exam beyond the heart 2 Jugular Venous Distention Pallor Cyanosis 3 Work of Breathing Normal infant breathing Quiet Tachypnea Increased Rate, Work of Breathing 4 Beyond the Chest Clubbing Observed in children older than 6 mos with chronic cyanosis Loss of the normal angle of the nail plate with the axis of the finger Abnormal sponginess of the base of the nail bed Increasing convexity of the nail Etiology: ? sludging 5 Chest ❖ Chest wall development and symmetry ❖ Long standing cardiomegaly can lead to hemihypertrophy and flared rib edge: Harrison’s groove or sulcus 6 Ready to Examine the Heart Palpation Auscultation General overview Defects Innocent versus pathologic 7 Cardiac Palpation ❖ Consistent approach: palm of your hand, hypothenar eminence, or finger tips ❖ Precordium, suprasternal notch ❖ PMI? ❖ RV impulse? ❖ Thrills? ❖ Heart Sounds? 8 Cardiac Auscultation Where to listen: ★ 4 main positions ★ Inching ★ Ancillary sites: don’t forget the head in infants 9 Cardiac Auscultation Focus separately on v Heart sounds: • S2 normal splitting and intensity? • Abnormal sounds? Clicks, gallops v Murmurs v Rubs 10 Cardiac Auscultation Etiology of heart sounds: Aortic and pulmonic valves actually close silently Heart sounds reflect vibrations of the cardiac structures after valve closure Sudden -

Selected Terms Used in Adult Congenital Heart Disease Jack M

SELECTED TERMS USED IN ADULT CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE JACK M. COLMAN | ERWIN NOTKER OECHSLIN | MATTHIAS GREUTMANN | DANIEL TOBLER ambiguus A With reference to cardiac situs, neither right nor left sided aberrant innominate artery (indeterminate). Latin spelling is generally used for situs ambig- A rare abnormality associated with right aortic arch compris- uus. Syn: ambiguous sidedness. See also situs. ing a sequence of arteries arising from the aortic arch—right carotid artery, right subclavian artery, and then (left) innomi- Amplatzer device nate artery—with the last passing behind the esophagus. This A group of self-centering devices delivered percutaneously by is in contrast to the general rule that the first arch artery gives catheter for closure of abnormal intracardiac and vascular con- rise to the carotid artery contralateral to the side of the aortic nections such as secundum atrial septal defect, patent foramen arch (ie, right carotid artery in left aortic arch and left carotid ovale or patent ductus arteriosus. artery in right aortic arch). Syn: retroesophageal innominate artery. Anderson-Fabry disease See Fabry disease aberrant subclavian artery Right subclavian artery arising from the aorta distal to the left aneurysm of sinus of Valsalva subclavian artery. Left aortic arch with (retroesophageal) aber- See sinus of Valsalva/aneurysm. rant right subclavian artery is the most common aortic arch anomaly. It was first described in 1735 by Hunauld and occurs anomalous pulmonary venous connection in 0.5% of the general population. Syn: lusorian artery. See also Pulmonary venous connection to the right side of the heart, vascular ring. which may be total or partial. -

Congenital Heart Disease Parent FAQ

Congenital Heart Disease Parent FAQ achd.stanfordchildrens.org | achd.stanfordhealthcare.org About Congenital Heart Disease What is congenital heart disease? Congenital heart disease, also called congenital heart defect (CHD), is a heart problem that a baby is born with. When the heart forms in the womb, it develops incorrectly and does not work properly, which changes how the blood flows through the heart. What causes congenital heart defects? In most cases, there is no clear cause. It can be linked to something out of the ordinary happening during gestation, including a viral infection or exposure to environmental factors. Or, it may be linked to a single gene defect or chromosome abnormalities. How common is CHD in the United States among children? Congenital heart defects are the most common birth defects in children in the United States. Approximately 1 in 100 babies are born with a heart defect. What are the most common types of congenital heart defects in children? In general, CHDs disrupt the flow of blood in the heart as it passes to the lungs or to the body. The most common congenital heart defects are abnormalities in the heart valves or a hole between the chambers of the heart (ventricles). Examples include ventricular septal defect (VSD), atrial septal defect (ASD), and bicuspid aortic valve. At the Betty Irene Moore Children’s Heart Center at Stanford Children’s Health, we are known across the nation and world for treating some of the most complex congenital heart defects with outstanding outcomes. Congenital Heart Disease Parent FAQ | 2 Is CHD preventable? In some cases, it could be preventable. -

Pulmonary-Atresia-Mapcas-Pavsdmapcas.Pdf

Normal Heart © 2012 The Children’s Heart Clinic NOTES: Children’s Heart Clinic, P.A., 2530 Chicago Avenue S, Ste 500, Minneapolis, MN 55404 West Metro: 612-813-8800 * East Metro: 651-220-8800 * Toll Free: 1-800-938-0301 * Fax: 612-813-8825 Children’s Minnesota, 2525 Chicago Avenue S, Minneapolis, MN 55404 West Metro: 612-813-6000 * East Metro: 651-220-6000 © 2012 The Children’s Heart Clinic Reviewed March 2019 Pulmonary Atresia, Ventricular Septal Defect and Major Aortopulmonary Collateral Arteries (PA/VSD/MAPCAs) Pulmonary atresia (PA), ventricular septal defect (VSD) and major aortopulmonary collateral arteries (MAPCAs) is a rare type of congenital heart defect, also referred to as Tetralogy of Fallot with PA/MAPCAs. Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is the most common cyanotic heart defect and occurs in 5-10% of all children with congenital heart disease. The classic description of TOF includes four cardiac abnormalities: overriding aorta, right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH), large perimembranous ventricular septal defect (VSD), and right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (RVOTO). About 20% of patients with TOF have PA at the infundibular or valvar level, which results in severe right ventricular outflow tract obstruction. PA means that the pulmonary valve is closed and not developed. When PA occurs, blood can not flow through the pulmonary arteries to the lungs. Instead, the child is dependent on a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) or multiple systemic collateral vessels (MAPCAs) to deliver blood to the lungs for oxygenation. These MAPCAs usually arise from the de- scending aorta and subclavian arteries. Commonly, the pulmonary arteries are abnormal, with hypoplastic (small and underdeveloped) central and branch pulmonary arteries and/ or non-confluent central pulmonary arteries. -

Pregnancy and Cardiovascular Disease

Pregnancy and Cardiovascular Disease Cindy M. Martin, M.D. Co-Director, Adult Congenital and Cardiovascular Genetics Center No Disclosures Objectives • Discuss the hemodynamic changes during pregnancy • Define the low, medium and high risk cardiac lesions as related to pregnancy • Review use of cardiovascular drugs in pregnancy Pregnancy and the Heart • 2-4% of pregnancies in women without preexisting cardiac abnormalities are complicated by maternal CV disease • In 2000, there were an estimated 1 million adult patients in the US with congenital heart disease (CHD), with the number increasing by 5% yearly • In 2005, the number of adult patients with CHD surpassed the number of children with CHD in the United States • CV and CHD disease does not always preclude pregnancy but may pose increase risk to mother and fetus Hemodynamic Changes during Pregnancy • Blood Volume – increases 40-50% • Heart rate – increases 10-15 bpm • SVR and PVR – decreases • Blood Pressure – decreases 10mmHg • Cardiac Output – increases 30-50% – Peaks at end of second trimester and plateaus until delivery • These changes are usually well tolerated Physiologic Changes in Pregnancy Hemodynamic Changes in Labor and Delivery • CO increases an additional 50% with each contraction – Uterine contraction displaces 300-500ml blood into the general circulation – Possible for the cardiac output to be 70-80% above baseline during labor and delivery • Mean arterial pressure also usually rises • Volume changes – Increased blood volume with uterine contraction – Increase venous -

Transcatheter Device Closure of Atrial Septal Defect in Dextrocardia with Situs Inversus Totalis

Case Report Nepalese Heart Journal 2019; Vol 16(1), 51-53 Transcatheter device closure of atrial septal defect in dextrocardia with situs inversus totalis Kiran Prasad Acharya1, Chandra Mani Adhikari1, Aarjan Khanal2, Sachin Dhungel1, Amrit Bogati1, Manish Shrestha3, Deewakar Sharma1 1 Department of Cardiology, Shahid Gangalal National Heart Centre, Kathmandu, Nepal 2 Department of Internal Medicine, Kathmandu Medical College, Kathmandu,Nepal 3 Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Shahid Gangalal National Heart Centre, Kathmandu, Nepal Corresponding Author: Chandra Mani Adhikari Department of Cardiology Shahid Gangalal National Heart Centre Kathmandu, Nepal Email: [email protected] Cite this article as: Acharya K P, Adhikari C M, Khanal A, et al. Transcatheter device closure of atrial septal defect in dextrocardia with situs inversus totalis. Nepalese Heart Journal 2019; Vol 16(1), 51-53 Received date: 17th February 2019 Accepted date: 16th April 2019 Abstract Only few cases of Device closure of atrial septal defect in dextrocardia with situs inversus totalis has been reported previously. We present a case of a 36 years old male, who had secundum type of atrial septal defect in dextrocardia with situs inversus totalis. ASD device closure was successfully done. However, we encountered few technical difficulties in this case which are discussed in this case review. Keywords: atrial septal defect; dextrocardia; transcatheter device closure, DOI: https://doi.org/10.3126/njh.v16i1.23901 Introduction There are only two case reported of closure of secundum An atrial septal defect (ASD) is an opening in the atrial ASD associated in patients with dextrocardia and situs inversus septum, excluding a patent foramen ovale.1 ASD is a common totalis.