Without a Theoretical Armature— a Group of Texts Specify- Ing Weaving's Dimensions and Goals— the Workshop's Pro- Ductio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bauhaus and Weimar Modernism

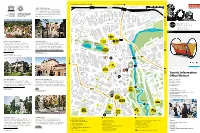

Buchenwald Memorial, Ettersburg Castle Sömmerda (B7 / B85) 100 m weimar UNESCO World Heritage 500 m Culture City of Europe The Bauhaus and its sites in Weimar and Dessau have been on the UNESCO list of World Heritage since 1996. There are three objects in Weimar: the main building of the Bauhaus University Weimar, the former School of Applied Arts and the Haus Am Horn. Tiefurt Mansion deutschEnglish Harry-Graf-Kessler-Str. 10 5 Tiefurt Mansion Bauhaus-Universität Weimar Nietzsche Archive B Jorge-Semprùn-Platz a Oskar-Schlemmer-Str. d The building ensemble by Henry van de Velde was Friedrich Nietzsche spent the last years of his life at H e Stèphane- r 1 s revolutionary in terms of architecture at the turn of the “Villa Silberblick”. His sister established the Nietzsche Archive f Hessel-Platz e l d century. These Art School buildings became the venue here after his death and had the interior and furnishings e r S where the State Bauhaus was founded in 1919, making designed by Henry van de Velde. The current exhibition is t r a ß “Weimar” and the “Bauhaus” landmarks in the history of entitled “Kampf um Nietzsche” (“Dispute about Nietzsche”). e modern architecture. Humboldtstrasse 36 13 Mon, Wed to Sun 2pm – 5pm Geschwister-Scholl-Strasse 2 Mon to Fri 10am – 6pm | Sat & Sun 10am – 4pm Über dem Kegeltor C o u d r a y s t Erfurt (B7) r a ß e Berkaer Bahnhof 8 CRADLE, DESIGN: PETER KELER, 1922 © KLASSIK STIFTUNG WEIMAR 17 Jena (B7) 3 Tourist Information Office Weimar Haus Hohe Pappeln Weimar Municipal Museum 20 16 Markt 10, 99423 Weimar The Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, the artistic The permanent exhibition of the Municipal Museum presents Tel + 49 (0) 3643 745 0 advisor of the grand duchy, built this house for his family of “Democracy from Weimar. -

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

Working Checklist 00

Taking a Thread for a Walk The Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 21, 2019 - June 01, 2020 WORKING CHECKLIST 00 - Introduction ANNI ALBERS (American, born Germany. 1899–1994) Untitled from Connections 1983 One from a portfolio of nine screenprints composition: 17 3/4 × 13 3/4" (45.1 × 34.9 cm); sheet: 27 3/8 × 19 1/2" (69.5 × 49.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in memory of Joseph Fearer Weber/Danilowitz 74 Wall, framed. Located next to projection in elevator bank ANNI ALBERS (American, born Germany. 1899–1994) Study for Nylon Rug from Connections 1983 One from a portfolio of nine screenprints composition: 20 5/8 × 15 1/8" (52.4 × 38.4 cm); sheet: 27 3/8 × 19 1/2" (69.5 × 49.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in memory of Joseph Fearer Weber/Danilowitz 75 Wall, framed. Located next to projection in elevator bank ANNI ALBERS (American, born Germany. 1899–1994) With Verticals from Connections 1983 One from a portfolio of nine screenprints composition: 19 3/8 × 14 1/4" (49.2 × 36.2 cm); sheet: 27 3/8 × 19 1/2" (69.5 × 49.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in memory of Joseph Fearer Weber/Danilowitz 73 Wall, framed. Located next to projection in elevator bank ANNI ALBERS (American, born Germany. 1899–1994) Orchestra III from Connections 1983 One from a portfolio of nine screenprints composition: 26 5/8 × 18 7/8" (67.6 × 47.9 cm); sheet: 27 3/8 × 19 1/2" (69.5 × 49.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. -

"Pictures Made of Wool": the Gender of Labor at the Bauhaus Weaving Workshop (1919-23)

Tai Smith - "Pictures made of wool": The Gender of Labor at the Bauhaus Weaving Workshop (1919-23) Back to Issue 4 "Pictures made of wool": The Gender of Labor at the Bauhaus Weaving Workshop (1919-23) by T'ai Smith © 2002 In 1926, one year after the Bauhaus had moved to Dessau, the weaving workshop master Gunta Stölzl dismissed the earlier, Weimar period textiles, such as Hedwig Jungnik’s wall hanging from 1922 [Fig. 1], as mere “pictures made of wool.”1 In this description she differentiated the early weavings, from the later, “progressivist” textiles of the Dessau workshop, which functioned industrially and architecturally: to soundproof space or to reflect light. The weavings of the Weimar years, by contrast, were autonomous, ornamental pieces, exhibited in the fashion of paintings. Stölzl saw this earlier work as a failure because it had no progressive aim. The wall hangings of the Weimar workshop were experimental—concerned with the pictorial elements of form and color—yet at that they were still inadequate, without the larger, transcendental goals of painting, as in the Bauhaus painter Wassily Kandinsky’s Red Spot II from 1921. Stölzl assessed the earlier, “aesthetic” period of weaving as unsuccessful, because its specific strengths were neither developed nor theorized. Weaving in the early Bauhaus lacked its own discursive parameters, just as it lacked a disciplinary history. Evaluated against the “true” picture, painting, weaving appeared a weaker, ineffectual medium. Stölzl’s remark references a fundamental problem that goes unquestioned in the literature concerning the Weimar Bauhaus weaving workshop and the feminized status of the medium. -

Bauhaus · Moderne · Design 2018 / 2019

Bauhaus · Moderne · Design 2018 / 2019 Editorial 1919 wurde in Thüringen mit dem Staatlichen Bauhaus zu Weimar nicht nur eine später weltberühmte Architektur- und Kunstschule begründet: Das Bauhaus war Ausdruck und Vorreiter einer international ausstrahlen- den Bewegung der Moderne. Es gilt heute als der wirkungsvollste deut- sche Kulturexport des 20. Jahrhunderts. Das Bauhaus steht für große gestalterische wie gesellschaftsreformerische Ideen. Es hat Architektur, Kunst und Design maßgeblich beeinflusst und wirkt auch noch heute nach. Mit dem Bauhaus verbinden sich Form- und Farbexperimente, Architekturikonen und Alltagsdesign, rauschende Feste und minimalisti- sche Bauten. Wo die Ursprünge dieser modernen Bewegung liegen, wie sie sich for- mierte, wie sie inspirierte und polarisierte – all das ist heute in und von Weimar aus eindrucksvoll wie in kaum einer anderen Region erfahrbar. Revolution. Neuanfang. Aufbruch in eine neue Zeit. In Deutschlands erster Demokratie, ebenfalls 1919 in Weimar begründet. Voller Hoffnung, mit unbedingtem Gestaltungs- und Veränderungswillen. Mut zum Experi- ment und Lebensfreude. Aber auch: Streit und Widerspruch. Ablehnung. Vertreibung. In Weimar und den umgebenden Städten Jena, Erfurt, Gera sowie dem Weimarer Umland erzählen eine Vielzahl von architektonischen Zeugnis- sen, künstlerischen Werken, historischen Schauplätzen, aktuellen Aus- stellungen und Veranstaltungen von der wechselvollen Geschichte des Bauhauses und der Moderne. Wer in Thüringen auf Reisen geht, trifft nicht nur auf die Überlieferungen der internationalen Kunstavantgarde von damals, sondern auch auf inspirierende Gestalter von heute und morgen. Nicht nur im Jahr 2019 – zum Jubiläum »100 jahre bauhaus« – bietet Thü- ringen ein reichhaltiges Kultur- und Besucherprogramm. Wir laden Sie ein, in Weimar die Wiege des Bauhauses und darüber hinaus eine ganze Region im Zeichen der Moderne zu entdecken. -

The Bauhaus 1 / 70

GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS 1 / 70 The Bauhaus 1 Art and Technology, A New Unity 3 2 The Bauhaus Workshops 13 3 Origins 26 4 Weimar 45 5 Dessau 57 6 Berlin 68 © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS 2 / 70 © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE ARTS & CRAFTS MOVEMENT 3 / 70 1919–1933 Art and Technology, A New Unity A German design school where ideas from all advanced art and design movements were explored, combined, and applied to the problems of functional design and machine production. © Kevin Woodland, 2020 Joost Schmidt, Exhibition Poster, 1923 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 4 / 70 1919–1933 The Bauhaus Twentieth-century furniture, architecture, product design, and graphics were shaped by the work of its faculty and students, and a modern design aesthetic emerged. MEGGS © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 5 / 70 1919–1933 The Bauhaus Ideas from all advanced art and design movements were explored, combined, and applied to the problems of functional design and machine production. MEGGS • The Arts & Crafts: Applied arts, craftsmanship, workshops, apprenticeship • Art Nouveau: Removal of ornament, application of form • Futurism: Typographic freedom • Dadaism: Wit, spontaneity, theoretical exploration • Constructivism: Design for the greater good • De Stijl: Reduction, simplification, refinement © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 6 / 70 1919–1933 -

The Analysis of the Influence and Inspiration of the Bauhaus on Contemporary Design and Education

Engineering, 2013, 5, 323-328 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/eng.2013.54044 Published Online April 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/eng) The Analysis of the Influence and Inspiration of the Bauhaus on Contemporary Design and Education Wenwen Chen1*, Zhuozuo He2 1Shanghai University of Engineering Science, Shanghai, China 2Zhongyuan University of Technology, Zhengzhou, China Email: *[email protected] Received October 11, 2012; revised February 24, 2013; accepted March 2, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Wenwen Chen, Zhuozuo He. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT The Bauhaus, one of the most prestigious colleges of fine arts, was founded in 1919 by the architect Walter Gropius. Although it is closed in the last century, its influence is still manifested in design industries now and will continue to spread its principles to designers and artists. Even, it has a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, fashion design and design education. Up until now, Bauhaus ideal has al- ways been a controversial focus that plays a crucial role in the field of design. Not only emphasizing function but also reflecting the human-oriented idea could be the greatest progress on modern design and manufacturing. Even more, harmonizing the relationship between nature and human is the ultimate goal for all the designers to create their artworks. This essay will analyze Bauhaus’s influence on modern design and manufacturing in terms of technology, architecture and design education. -

Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity the Museum of Modern Art, New York November 08, 2009-January 25, 2010

Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity The Museum of Modern Art, New York November 08, 2009-January 25, 2010 ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Upholstery, drapery, and wall-covering samples 1923-29 Wool, rayon, cotton, linen, raffia, cellophane, and chenille Between 8 1/8 x 3 1/2" (20.6 x 8.9 cm) and 4 3/8 x 16" (11.1 x 40.6 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the designer or Gift of Josef Albers ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1925 Silk, cotton, and acetate 57 1/8 x 36 1/4" (145 x 92 cm) Die Neue Sammlung - The International Design Museum Munich ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1925 Wool and silk 7' 8 7.8" x 37 3.4" (236 x 96 cm) Die Neue Sammlung - The International Design Museum Munich ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1926 Silk (three-ply weave) 70 3/8 x 46 3/8" (178.8 x 117.8 cm) Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Association Fund Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity - Exhibition Checklist 10/27/2009 Page 1 of 80 ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Tablecloth Fabric Sample 1930 Mercerized cotton 23 3/8 x 28 1/2" (59.3 x 72.4 cm) Manufacturer: Deutsche Werkstaetten GmbH, Hellerau, Germany The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase Fund JOSEF ALBERS German, 1888-1976; at Bauhaus 1920–33 Gitterbild I (Grid Picture I; also known as Scherbe ins Gitterbild [Glass fragments in grid picture]) c. -

Anni Albers Large Print Guide

ANNI ALBERS 11 October 2018 – 27 January 2018 LARGE PRINT GUIDE Please return to the holder CONTENTS Room 1 ................................................................................3 Room 2 ................................................................................9 Room 3 ..............................................................................34 Room 4 ..............................................................................49 Room 5 ..............................................................................60 Room 6 ..............................................................................70 Room 7 ..............................................................................90 Room 8 ..............................................................................96 Room 9 ............................................................................ 109 Room 10 .......................................................................... 150 Room 11 .......................................................................... 183 2 ROOM 1 3 INTRODUCTION Anni Albers (1899–1994) was among the leading innovators of twentieth-century modernist abstraction, committed to uniting the ancient craft of weaving with the language of modern art. As an artist, designer, teacher and writer, she transformed the way weaving could be understood as a medium for art, design and architecture. Albers was introduced to hand-weaving at the Bauhaus, a radical art school in Weimar, Germany. Throughout her career Albers explored the possibilities -

Getty Research Institute | June 11 – October 13, 2019

Getty Research Institute | June 11 – October 13, 2019 OBJECT LIST Founding the Bauhaus Programm des Staatlichen Bauhauses in Weimar (Program of the State Bauhaus in Weimar) 1919 Walter Gropius (German, 1883–1969), author Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871–1956), illustrator Letterpress and woodcut on paper 850513 Idee und Aufbau des Staatlichen Bauhauses Weimar (Idea and structure of the State Bauhaus Weimar) Munich: Bauhausverlag, 1923 Walter Gropius (German, 1883–1969), author Letterpress on paper 850513 Bauhaus Seal 1919 Peter Röhl (German, 1890–1975) Relief print From Walter Gropius, Satzungen Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar (Weimar, January 1921) 850513 Bauhaus Seal Oskar Schlemmer (German, 1888–1943) Lithograph From Walter Gropius, Satzungen Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar (Weimar, July 1922) 850513 Diagram of the Bauhaus Curriculum Walter Gropius (German, 1883–1969) Lithograph From Walter Gropius, Satzungen Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar (Weimar, July 1922) 850513 1 The Getty Research Institute 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100, Los Angeles, CA 90049 www.getty.edu German Expressionism and the Bauhaus Brochure for Arbeitsrat für Kunst Berlin (Workers’ Council for Art Berlin) 1919 Max Pechstein (German, 1881–1955) Woodcut 840131 Sketch of Majolica Cathedral 1920 Hans Poelzig (German, 1869–1936) Colored pencil and crayon on tracing paper 870640 Frühlicht Fall 1921 Bruno Taut (German, 1880–1938), editor Letterpress 84-S222.no1 Hochhaus (Skyscraper) Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (German, 1886–1969) Offset lithograph From Frühlicht, no. 4 (Summer 1922): pp. 122–23 84-S222.no4 Ausstellungsbau in Glas mit Tageslichtkino (Exhibition building in glass with daylight cinema) Bruno Taut (German, 1880–1938) Offset lithographs From Frühlicht, no. 4 (Summer 1922): pp. -

11 71 126 Bruno Adler Lotte Collein Walter Gropius Weimar in Those

11 71 126 Bruno Adler Lotte Collein Walter Gropius Weimar in Those Days Photography The Idea of the at the Bauhaus Bauhaus: The Battle 16 for New Educational Josef Albers 76 Foundations Thirteen Years Howard at the Bauhaus Dearstyne 131 Mies van der Rohe’s Hans 22 Teaching at the Haffenrichter Alfred Arndt Bauhaus in Dessau Lothar Schreyer how i got to the and the Bauhaus bauhaus in weimar 83 Stage Walter voxel 30 The Bauhaus 137 Herbert Bayer Style: a Myth Gustav Homage to Gropius Hassenpflug 89 A Look at the Bauhaus 33 Lydia Today Hannes Beckmann Driesch-Foucar Formative Years Memories of the 139 Beginnings of the Fritz Hesse 41 Dornburg Pottery Dessau Max Bill Workshop of the State and the Bauhaus the bauhaus must go on Bauhaus in Weimar, 1920-1923 145 43 Hubert Hoffmann Sandor Bortnyik 100 the revival of the Something T. Lux Feininger bauhaus after 1945 on the Bauhaus The Bauhaus: Evolution of an Idea 150 50 Hubert Hoffmann Marianne Brandt 117 the dessau and the Letter to the Max Gebhard moscow bauhaus Younger Generation Advertising (VKhUTEMAS) and Typography 55 at the Bauhaus 156 Hin Bredendieck Johannes Itten The Preliminary Course 121 How the Tremendous and Design Werner Graeff Influence of the The Bauhaus, Bauhaus Began 64 the De Stijl group Paul Citroen in Weimar, and the 160 Mazdaznan Constructivist Nina Kandinsky at the Bauhaus Congress of 1922 Interview 167 226 278 Felix Klee Hannes Meyer Lou Scheper My Memories of the On Architecture Retrospective Weimar Bauhaus 230 283 177 Lucia Moholy Kurt Schmidt Heinrich Kdnig Questions -

Biografie Georg Muche

Georg Muche Biografie 1895 Georg Muche wird am 8. Mai als Sohn eines Beamten in Querfurt geboren. Er verbringt Kindheit und Jugend in der Rhön. 1913 Studium der Malerei an der Azbé-Schule in München, das er nach einem Jahr aufgibt und nach Berlin geht. Lernt Arbeiten von Wassily Kandisky kennen. Im Spätsommer 1913 besuchte ich in München das Atelier, in dem Kandinsky und Jawlensky vor Jahren Malen gelernt hatten. Ich musste dort in der Art von Wilhelm Leibl Köpfe und Akte mit Glanzlichtern auf der Nasenspitze zeichnen und mein Handwerk gründlich erlernen…So jung am Jahren war ich aufgebrochen und kam doch zu spät. Eine Besucherin der Ausstellung („Der blaue Reiter“) muss das Staunen beobachtet haben, mit dem meine Augen auf den Bildern verweilten. Es war Marianne von Werefkin. Sie machte mich aufmerksam auf Jawlensky und Kandinsky, die im Hintergrund miteinander sprachen...Sie hatten die neue Welt entdeckt! Ich erkannte zugleich, dass ich in abstrakten Gefilden nicht suchen durfte, wenn ich Entdeckungen machen wollte. 1915 Zusammenarbeit mit Herwarth Walden im „Sturm“. Ein Jahr später erste Ausstellung in der „Sturm“-Galerie mit Max Ernst, später weitere Ausstellungen mit Alexander Archipenko und Paul Klee. Muche wird wegen seiner außergewöhnlichen Fähigkeiten Lehrer an der „Sturm“- Kunstschule. Theodor Däubler schilderte jene Bilder in seinen Kritiken: „Die geometrisch unbeweglichen Bilder des jungen Georg Muche erinnern an Maschinen im weißglühenden und rotglühenden Zustand…Nicht Vorgänge unter Menschen beschäftigen seine Einbildungskraft, sondern eine Art übersinnlicher Dimension, ein Wissen um Raumbedingtheiten, damit Eruptionen von Leidenschaften in die Welt hereinbrechen können, oder er steigert den Zufall, dass eine Kugel in einem vom Rahmen eingeschlossenen Raum sich öffnet oder verschließt.