Embryology and Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 Embryology and Development

BIOL 6505 − INTRODUCTION TO FETAL MEDICINE 3. EMBRYOLOGY AND DEVELOPMENT Arlet G. Kurkchubasche, M.D. INTRODUCTION Embryology – the field of study that pertains to the developing organism/human Basic embryology –usually taught in the chronologic sequence of events. These events are the basis for understanding the congenital anomalies that we encounter in the fetus, and help explain the relationships to other organ system concerns. Below is a synopsis of some of the critical steps in embryogenesis from the anatomic rather than molecular basis. These concepts will be more intuitive and evident in conjunction with diagrams and animated sequences. This text is a synopsis of material provided in Langman’s Medical Embryology, 9th ed. First week – ovulation to fertilization to implantation Fertilization restores 1) the diploid number of chromosomes, 2) determines the chromosomal sex and 3) initiates cleavage. Cleavage of the fertilized ovum results in mitotic divisions generating blastomeres that form a 16-cell morula. The dense morula develops a central cavity and now forms the blastocyst, which restructures into 2 components. The inner cell mass forms the embryoblast and outer cell mass the trophoblast. Consequences for fetal management: Variances in cleavage, i.e. splitting of the zygote at various stages/locations - leads to monozygotic twinning with various relationships of the fetal membranes. Cleavage at later weeks will lead to conjoined twinning. Second week: the week of twos – marked by bilaminar germ disc formation. Commences with blastocyst partially embedded in endometrial stroma Trophoblast forms – 1) cytotrophoblast – mitotic cells that coalesce to form 2) syncytiotrophoblast – erodes into maternal tissues, forms lacunae which are critical to development of the uteroplacental circulation. -

Determination of Cell Development, Differentiation and Growth

Pediat. Res. I: 395-408 (1967) Determination of Cell Development, Differentiation and Growth A Review D.M.BROWN[ISO] Department of Pediatrics, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA Introduction plasmic synthesis, water uptake, or, in the case of intact tissue, intercellular deposition. It may include prolifera It has become increasingly apparent that the basis for tion or the multiplication of identical cells and may be biologic variation in relation to disease states is in accompanied by differentiation which implies anatomical large part predetermined from early embryonic stages. as well as functional changes. The number of cellular Consideration of variations of growth and development units in a tissue may be related to the deoxyribonucleic must take into account the genetic constitution and acid (DNA) content or nucleocytoplasmic units [24, early embryonic events of tissue and organ develop 59, 143]. Differentiation may refer to physical and ment. chemical organization of subcellular components or The incidence of congenital malformation has been to changes in the structure and organization of cells estimated to be 2 to 3 percent of all live born infants and leading to specialized organs. may double by one year [133]. Minor abnormalities are even more common [79]. Furthermore, the large variety of well-defined 'inborn errors of metabolism', Control of Embryonic Chemical Development as well as the less apparent molecular and chromosomal abnormalities, should no doubt be considered as mal Protein syntheses during oogenesis and embryogenesis formations despite the possible lack of gross somatic are guided by nuclear and nucleolar ribonucleic acid aberrations. Low birth weight is a frequent accom (RNA) which are in turn controlled by primer DNA. -

Te2, Part Iii

TERMINOLOGIA EMBRYOLOGICA Second Edition International Embryological Terminology FIPAT The Federative International Programme for Anatomical Terminology A programme of the International Federation of Associations of Anatomists (IFAA) TE2, PART III Contents Caput V: Organogenesis Chapter 5: Organogenesis (continued) Systema respiratorium Respiratory system Systema urinarium Urinary system Systemata genitalia Genital systems Coeloma Coelom Glandulae endocrinae Endocrine glands Systema cardiovasculare Cardiovascular system Systema lymphoideum Lymphoid system Bibliographic Reference Citation: FIPAT. Terminologia Embryologica. 2nd ed. FIPAT.library.dal.ca. Federative International Programme for Anatomical Terminology, February 2017 Published pending approval by the General Assembly at the next Congress of IFAA (2019) Creative Commons License: The publication of Terminologia Embryologica is under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0) license The individual terms in this terminology are within the public domain. Statements about terms being part of this international standard terminology should use the above bibliographic reference to cite this terminology. The unaltered PDF files of this terminology may be freely copied and distributed by users. IFAA member societies are authorized to publish translations of this terminology. Authors of other works that might be considered derivative should write to the Chair of FIPAT for permission to publish a derivative work. Caput V: ORGANOGENESIS Chapter 5: ORGANOGENESIS -

The Rotated Hypoblast of the Chicken Embryo Does Not Initiate an Ectopic Axis in the Epiblast

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 92, pp. 10733-10737, November 1995 Developmental Biology The rotated hypoblast of the chicken embryo does not initiate an ectopic axis in the epiblast ODED KHANER Department of Cell and Animal Biology, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel 91904 Communicated by John Gerhart, University of California, Berkeley, CA, July 14, 1995 ABSTRACT In the amniotes, two unique layers of cells, of the hypoblast and that the orientation of the streak and axis the epiblast and the hypoblast, constitute the embryo at the can be predicted from the polarity of the stage XIII epiblast. blastula stage. All the tissues of the adult will derive from the Still it was thought that the polarity of the epiblast is sufficient epiblast, whereas hypoblast cells will form extraembryonic for axial development in experimental situations, although in yolk sac endoderm. During gastrulation, the endoderm and normal development the polarity of the hypoblast is dominant the mesoderm of the embryo arise from the primitive streak, (5, 6). These reports (1-3, 5, 6), taken together, would imply which is an epiblast structure through which cells enter the that cells of the hypoblast not only have the ability to change interior. Previous investigations by others have led to the the fate of competent cells in the epiblast to initiate an ectopic conclusion that the avian hypoblast, when rotated with regard axis, but also have the ability to repress the formation of the to the epiblast, has inductive properties that can change the original axis in committed cells of the epiblast. At the same fate of competent cells in the epiblast to form an ectopic time, the results showed that the epiblast is not wholly depen- embryonic axis. -

Gastrulation

Embryology of the spine and spinal cord Andrea Rossi, MD Neuroradiology Unit Istituto Giannina Gaslini Hospital Genoa, Italy [email protected] LEARNING OBJECTIVES: LEARNING OBJECTIVES: 1) To understand the basics of spinal 1) To understand the basics of spinal cord development cord development 2) To understand the general rules of the 2) To understand the general rules of the development of the spine development of the spine 3) To understand the peculiar variations 3) To understand the peculiar variations to the normal spine plan that occur at to the normal spine plan that occur at the CVJ the CVJ Summary of week 1 Week 2-3 GASTRULATION "It is not birth, marriage, or death, but gastrulation, which is truly the most important time in your life." Lewis Wolpert (1986) Gastrulation Conversion of the embryonic disk from a bilaminar to a trilaminar arrangement and establishment of the notochord The three primary germ layers are established The basic body plan is established, including the physical construction of the rudimentary primary body axes As a result of the movements of gastrulation, cells are brought into new positions, allowing them to interact with cells that were initially not near them. This paves the way for inductive interactions, which are the hallmark of neurulation and organogenesis Day 16 H E Day 15 Dorsal view of a 0.4 mm embryo BILAMINAR DISK CRANIAL Epiblast faces the amniotic sac node Hypoblast Primitive pit (primitive endoderm) faces the yolk sac Primitive streak CAUDAL Prospective notochordal cells Dias Dias During -

Vocabulario De Morfoloxía, Anatomía E Citoloxía Veterinaria

Vocabulario de Morfoloxía, anatomía e citoloxía veterinaria (galego-español-inglés) Servizo de Normalización Lingüística Universidade de Santiago de Compostela COLECCIÓN VOCABULARIOS TEMÁTICOS N.º 4 SERVIZO DE NORMALIZACIÓN LINGÜÍSTICA Vocabulario de Morfoloxía, anatomía e citoloxía veterinaria (galego-español-inglés) 2008 UNIVERSIDADE DE SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTELA VOCABULARIO de morfoloxía, anatomía e citoloxía veterinaria : (galego-español- inglés) / coordinador Xusto A. Rodríguez Río, Servizo de Normalización Lingüística ; autores Matilde Lombardero Fernández ... [et al.]. – Santiago de Compostela : Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Servizo de Publicacións e Intercambio Científico, 2008. – 369 p. ; 21 cm. – (Vocabularios temáticos ; 4). - D.L. C 2458-2008. – ISBN 978-84-9887-018-3 1.Medicina �������������������������������������������������������������������������veterinaria-Diccionarios�������������������������������������������������. 2.Galego (Lingua)-Glosarios, vocabularios, etc. políglotas. I.Lombardero Fernández, Matilde. II.Rodríguez Rio, Xusto A. coord. III. Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. Servizo de Normalización Lingüística, coord. IV.Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. Servizo de Publicacións e Intercambio Científico, ed. V.Serie. 591.4(038)=699=60=20 Coordinador Xusto A. Rodríguez Río (Área de Terminoloxía. Servizo de Normalización Lingüística. Universidade de Santiago de Compostela) Autoras/res Matilde Lombardero Fernández (doutora en Veterinaria e profesora do Departamento de Anatomía e Produción Animal. -

The Genetic Basis of Mammalian Neurulation

REVIEWS THE GENETIC BASIS OF MAMMALIAN NEURULATION Andrew J. Copp*, Nicholas D. E. Greene* and Jennifer N. Murdoch‡ More than 80 mutant mouse genes disrupt neurulation and allow an in-depth analysis of the underlying developmental mechanisms. Although many of the genetic mutants have been studied in only rudimentary detail, several molecular pathways can already be identified as crucial for normal neurulation. These include the planar cell-polarity pathway, which is required for the initiation of neural tube closure, and the sonic hedgehog signalling pathway that regulates neural plate bending. Mutant mice also offer an opportunity to unravel the mechanisms by which folic acid prevents neural tube defects, and to develop new therapies for folate-resistant defects. 6 ECTODERM Neurulation is a fundamental event of embryogenesis distinct locations in the brain and spinal cord .By The outer of the three that culminates in the formation of the neural tube, contrast, the mechanisms that underlie the forma- embryonic (germ) layers that which is the precursor of the brain and spinal cord. A tion, elevation and fusion of the neural folds have gives rise to the entire central region of specialized dorsal ECTODERM, the neural plate, remained elusive. nervous system, plus other organs and embryonic develops bilateral neural folds at its junction with sur- An opportunity has now arisen for an incisive analy- structures. face (non-neural) ectoderm. These folds elevate, come sis of neurulation mechanisms using the growing battery into contact (appose) in the midline and fuse to create of genetically targeted and other mutant mouse strains NEURAL CREST the neural tube, which, thereafter, becomes covered by in which NTDs form part of the mutant phenotype7.At A migratory cell population that future epidermal ectoderm. -

Embryology of Branchial Region

TRANSCRIPTIONS OF NARRATIONS FOR EMBRYOLOGY OF THE BRANCHIAL REGION Branchial Arch Development, slide 2 This is a very familiar picture - a median sagittal section of a four week embryo. I have actually done one thing correctly, I have eliminated the oropharyngeal membrane, which does disappear sometime during the fourth week of development. The cloacal membrane, as you know, doesn't disappear until the seventh week, and therefore it is still intact here, but unlabeled. But, I've labeled a couple of things not mentioned before. First of all, the most cranial part of the foregut, that is, the part that is cranial to the chest region, is called the pharynx. The part of the foregut in the chest region is called the esophagus; you probably knew that. And then, leading to the pharynx from the outside, is an ectodermal inpocketing, which is called the stomodeum. That originally led to the oropharyngeal membrane, but now that the oropharyngeal membrane is ruptured, the stomodeum is a pathway between the amniotic cavity and the lumen of the foregut. The stomodeum is going to become your oral cavity. Branchial Arch Development, slide 3 This is an actual picture of a four-week embryo. It's about 5mm crown-rump length. The stomodeum is labeled - that is the future oral cavity that leads to the pharynx through the ruptured oropharyngeal membrane. And I've also indicated these ridges separated by grooves that lie caudal to the stomodeum and cranial to the heart, which are called branchial arches. Now, if this is a four- week old embryo, clearly these things have developed during the fourth week, and I've never mentioned them before. -

Segmentation and Specification of the Drosophila Mesoderm

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on September 25, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Segmentation and specification of the Drosophila mesoderm Natalia Azpiazu, 1,3 Peter A. Lawrence, 2 Jean-Paul Vincent, 2 and Manfred Frasch 1'4 1Brookdale Center for Molecular Biology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York 10029 USA; 2Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge CB2 2QH, UK Patterning of the developing mesoderm establishes primordia of the visceral, somatic, and cardiac tissues at defined anteroposterior and dorsoventral positions in each segment. Here we examine the mechanisms that locate and determine these primordia. We focus on the regulation of two mesodermal genes: bagpipe (hap), which defines the anlagen of the visceral musculature of the midgut, and serpent (srp), which marks the anlagen of the fat body. These two genes are activated in specific groups of mesodermal cells in the anterior portions of each parasegment. Other genes mark the anlagen of the cardiac and somatic mesoderm and these are expressed mainly in cells derived from posterior portions of each parasegment. Thus the parasegments appear to be subdivided, at least with respect to these genes, a subdivision that depends on pair-rule genes such as even-skipped (eve). We show with genetic mosaics that eve acts autonomously within the mesoderm. We also show that hedgehog (hh) and wingless (wg) mediate pair-rule gene functions in the mesoderm, probably partly by acting within the mesoderm and partly by inductive signaling from the ectoderm, hh is required for the normal activation of hap and srp in anterior portions of each parasegment, whereas wg is required to suppress bap and srp expression in posterior portions. -

Mesoderm Induction and the Control of Gastrulation in Xenopus Laevis:The

Development 108, 229-238 (1990) 229 Printed in Great Britain ©The Company of Biologists Limited 1990 Mesoderm induction and the control of gastrulation in Xenopus laevis: the roles of fibronectin and integrins J. C. SMITH1, K. SYMESH, R. O. HYNES2'3 and D. DeSIMONE3* ' Laboratory of Embryogenesis, National Institute for Medical Research, The Ridgeway, Mill Hill, London NW71AA, UK ^Howard Hughes Medical Institute and ^Center for Cancer Research, Department of Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA * Present address: University of Virginia, Health Sciences Center, Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Box 439, School of Medicine, Charlottesville, VA 22908, USA t Present address: Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, 385 LSA, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA Summary Exposure of isolated Xenopus animal pole ectoderm to diated cell migration is not required for convergent the XTC mesoderm-inducing factor (XTC-MIF) causes extension. the tissue to undergo gastrulation-like movements. In We have investigated the molecular basis of XTC- this paper, we take advantage of this observation to MIF-induced gastrulation-like movements by measuring investigate the control of various aspects of gastrulation rates of synthesis of fibronectin and of the integrin f}y in Xenopus. chain in induced and control explants. No significant Blastomcres derived from induced animal pole regions differences were observed, and this suggests that gastru- are able, like marginal zone cells, but unlike control lation is not initiated simply by control of synthesis of animal pole blastomeres, to spread and migrate on a these molecules. In future work, we intend to investigate fibronectin-coated surface. -

Stages of Embryonic Development of the Zebrafish

DEVELOPMENTAL DYNAMICS 2032553’10 (1995) Stages of Embryonic Development of the Zebrafish CHARLES B. KIMMEL, WILLIAM W. BALLARD, SETH R. KIMMEL, BONNIE ULLMANN, AND THOMAS F. SCHILLING Institute of Neuroscience, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403-1254 (C.B.K., S.R.K., B.U., T.F.S.); Department of Biology, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 03755 (W.W.B.) ABSTRACT We describe a series of stages for Segmentation Period (10-24 h) 274 development of the embryo of the zebrafish, Danio (Brachydanio) rerio. We define seven broad peri- Pharyngula Period (24-48 h) 285 ods of embryogenesis-the zygote, cleavage, blas- Hatching Period (48-72 h) 298 tula, gastrula, segmentation, pharyngula, and hatching periods. These divisions highlight the Early Larval Period 303 changing spectrum of major developmental pro- Acknowledgments 303 cesses that occur during the first 3 days after fer- tilization, and we review some of what is known Glossary 303 about morphogenesis and other significant events that occur during each of the periods. Stages sub- References 309 divide the periods. Stages are named, not num- INTRODUCTION bered as in most other series, providing for flexi- A staging series is a tool that provides accuracy in bility and continued evolution of the staging series developmental studies. This is because different em- as we learn more about development in this spe- bryos, even together within a single clutch, develop at cies. The stages, and their names, are based on slightly different rates. We have seen asynchrony ap- morphological features, generally readily identi- pearing in the development of zebrafish, Danio fied by examination of the live embryo with the (Brachydanio) rerio, embryos fertilized simultaneously dissecting stereomicroscope. -

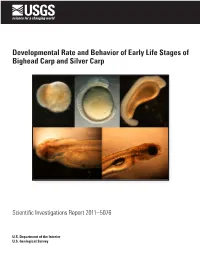

Developmental Rate and Behavior of Early Life Stages of Bighead Carp and Silver Carp

Developmental Rate and Behavior of Early Life Stages of Bighead Carp and Silver Carp Scientific Investigations Report 2011–5076 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover images. Left to right (top) silver carp embryo at morula stage, silver carp embryo at olfactory placode stage, silver carp embryo at otolith appearance stage, (bottom) silver carp larvae at gill filament stage, silver carp larvae at one-chamber gas bladder stage. Developmental Rate and Behavior of Early Life Stages of Bighead Carp and Silver Carp By Duane C. Chapman and Amy E. George Scientific Investigations Report 2011–5076 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2011 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Chapman, D.C., George, A.E., 2011, Developmental rate and behavior of early life stages of bighead carp and silver carp: U.S.