MANNION V. COORS BREWING CO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

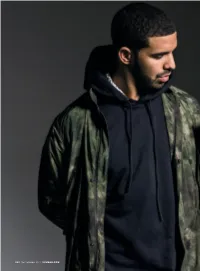

040 September 2013 Xxlmag.Com Everything I Am Drake's on Top, He's Been There for a While, and He Doesn't Seem to Be Going Anywhere

040 SEPTEMBER 2013 XXLMAG.COM EVERYTHING I AM DRAKE'S ON TOP, HE'S BEEN THERE FOR A WHILE, AND HE DOESN'T SEEM TO BE GOING ANYWHERE. HATERS CAN HATE, BUT IT WON'T MATTER. INTERVIEW THOMAS GOLIANOPOULOS IMAGES JONATHAN MANNION XXLMAG.COM SEPTEMBER 2013 041 One of the biggest rappers in the world lives on a busy street in Yorkville, an upscale neighborhood in Toronto fi lled with designer boutiques, European tourists and gelato shops. Aubrey Drake Graham, 26, is the half-Jewish, half- African-American former child acting star from T Dot, who has dominated hip-hop culture since his landmark mixtape So Far Gone heralded his arrival in early 2009. Since then, Drake, who signed to Cash Money/Universal that same year after being scooped up by Lil Wayne, has released two albums (Thank Me Later in 2010 and Take Care in 2011), collected an impressive 10 No. 1 records on the Billboard Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart, coined a generational slogan (YOLO: You Only Live Once from his record “The Motto”) and maintained a ubiquitous presence through his guest appearances; four of the six nominees—“Fuckin’ Problems,” “Poetic Justice,” “No Lie” and “Pop That”— for Best Collaboration at this June’s BET Awards featured Drake. It’s an exciting time for Drake, who releases his third solo album, Nothing Was The Same, on September 17. This summer was hyped as a showdown of sorts between himself, Kanye West and Jay Z, but after Yeezus polarized listeners and Magna Carta… Holy Grail revealed itself as more marketing coup than artistic statement, it’s clear the throne is there for the taking. -

THOMAS MARVEL Director of Photography 2821 3Rd Street Santa Monica, CA 90405

THOMAS MARVEL Director of Photography 2821 3rd Street Santa Monica, CA 90405 1986- Hamilton College, Clinton NY, Bachelor of Arts 1987- Grotowski Studio Theatre, Wroclaw, Poland 1987-1989 Production Assistant 1989-1994 Studio Lighting Technician 1994-1998 Chief Lighting Technician 1998- Present, Director of Photography 2015 NARRATIVE “The Nice Guys” Camera Operator, Directed by Shane Black, DP Philippe Rousselot COMMERCIALS Harbin Beer, “Shaq and Friends” directed by Gil Green MUSIC VIDEOS Mary J. Blige “Doubt” directed by Ethan Lader 2014 COMMERCIALS Sandals Foundation, “Soles of Youth” directed by Gil Green Mexico CPTM Tourismo, “Vivirlo para Creerlo” directed by Michael Abt Diners Club, “Club Miles” directed by Alejandro Dube Novo Nordisk, “Rev Run Diabetes Awareness” directed by Ron Jacobs Novo Nordisk , “Debbie Allen Diabetes Awareness” directed by Ron Jacobs Domino’s Pizza, “Must Try” directed by Francisco Pugliese MUSIC VIDEOS Wisin ft. Pitbull, “Control” directed by Carlos Perez Ricardo Arjona, “Apnea” directed by Carlos Perez 2013 NARRATIVE “The Veil” feature film directed by Brent Ryan Green COMMERCIALS Park Hyatt, “Anthem” directed by Josh Hayward Nissan, “Skylar Gray” directed by Declan Whitbeloom 1 Pepsi, “Wally Lopez” directed by Gil Green Sanofi Pasteur, “Dana Torres PSA” directed by Ron Jacobs YouTube, “Comedy Week Promo with Arnold Schwarzenneger” directed by Nick Ryan Tigo, “Verdades” directed by Roberto Mancia Valspar Paint, “Tori and Dean” directed by Natalie Barandes WalMart, “Gain” directed by Francisco Pugliese -

Eminem the Complete Guide

Eminem The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Wed, 01 Feb 2012 13:41:34 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Eminem 1 Eminem discography 28 Eminem production discography 57 List of awards and nominations received by Eminem 70 Studio albums 87 Infinite 87 The Slim Shady LP 89 The Marshall Mathers LP 94 The Eminem Show 107 Encore 118 Relapse 127 Recovery 145 Compilation albums 162 Music from and Inspired by the Motion Picture 8 Mile 162 Curtain Call: The Hits 167 Eminem Presents: The Re-Up 174 Miscellaneous releases 180 The Slim Shady EP 180 Straight from the Lab 182 The Singles 184 Hell: The Sequel 188 Singles 197 "Just Don't Give a Fuck" 197 "My Name Is" 199 "Guilty Conscience" 203 "Nuttin' to Do" 207 "The Real Slim Shady" 209 "The Way I Am" 217 "Stan" 221 "Without Me" 228 "Cleanin' Out My Closet" 234 "Lose Yourself" 239 "Superman" 248 "Sing for the Moment" 250 "Business" 253 "Just Lose It" 256 "Encore" 261 "Like Toy Soldiers" 264 "Mockingbird" 268 "Ass Like That" 271 "When I'm Gone" 273 "Shake That" 277 "You Don't Know" 280 "Crack a Bottle" 283 "We Made You" 288 "3 a.m." 293 "Old Time's Sake" 297 "Beautiful" 299 "Hell Breaks Loose" 304 "Elevator" 306 "Not Afraid" 308 "Love the Way You Lie" 324 "No Love" 348 "Fast Lane" 356 "Lighters" 361 Collaborative songs 371 "Dead Wrong" 371 "Forgot About Dre" 373 "Renegade" 376 "One Day at a Time (Em's Version)" 377 "Welcome 2 Detroit" 379 "Smack That" 381 "Touchdown" 386 "Forever" 388 "Drop the World" -

MBW Yearbook

2018 2018 2018 2019 2019 2019 2018 2018 2018 2019 2019 2019 2018 2018 2018 2019 2019 2019 2018 2018 2018 2019 2019 2019 2018 2018 2018YEARBOOK 2019 2019 2019 2018 20182018/2019 2018 2019 2019 2019 2018 2018 2018 2019 2019 2019 2018 2018 2018 2019 2019 2019 2018 2018 2018 2019 2019 2019 2018 2018 2018 2019 2019 2019 2018 2018 2018 2019 2019 2019 2018 2018 2018 2019 2019 2019 2018 2018 2018 2019 2019 2019 2018 2018 2018 2019 2019 2019 2018 2018 2018Brought to2019 you by 2019 2019 2018 2018 2018 2019 2019 2019 2018 2018 2018 2019 2019 2019 1 2 3 Are you making the most of your success? Our efficient international payments, transparent foreign exchange and smart treasury management services will help you and your artists realise your global ambitions. +44 (0)20 3735 1735 | [email protected] | CENTTRIPMUSIC.COM Centtrip Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) as an Electronic Money Institution (EMI). Our firm reference number is 900717. For more information on EMIs please visit the FCA’s website. The Centtrip Prepaid Mastercard is issued by Prepaid Financial Services Limited (PFS) pursuant to a licence from Mastercard International Incorporated. PFS is also authorised and regulated by the FCA as an Electronic Money Institution (firm reference number 900036). Their registered address is Fifth Floor, Langham House, 302–308 Regent Street, London W1B 3AT. 4 5 Contents Lyor Cohen, YouTube 08 Dre London, London Ent 16 David Joseph, Universal Music 24 Carolyn Williams, RCA 32 Paul Rosenberg, Goliath Artists/Def -

This Year's 40 Under 40

20120326-NEWS--0050-NAT-CCI-CN_-- 3/23/2012 6:33 PM Page 1 ® VOL. XXVIII, NO. 13 www.crainsnewyork.com MARCH 26-APRIL 1, 2012 PRICE: $3.00 HEREHERE THEYTHEY ARE!ARE! THISTHIS YEAR’SYEAR’S 4040 UNDERUNDER 4040 DoSomething.org’s ALSO INSIDE ARIA FINGER Andrew Cuomo: ‘Her energy is almost NY’s take-charge guv? contagious,’ said a fan Or control freak? of the 29-year-old It all depends on MEET THEM ALL: Pages F1-F25 where you sit Action! Film studios 13 5 running out of space ELECTRONIC EDITION A not-so-wonderful NEWSPAPER turn for stellar bank 71486 01068 0 CN015034.qxp 3/21/2012 2:19 PM Page 1 I am Indian Point. I am Theresa Motko, one of 1,200 workers at the Indian Point Energy Center who takes personal pride Theresa Motko, 33, is an in helping to provide New York City and Westchester Electrical Engineer at the with over 25 percent of our power. That power is clean, Indian Point Energy Center. it’s reliable, and it’s among the lowest cost electricity in the region. We are New Yorkers. We are your neighbors, our Lately a few people have been talking about replacing children attend the same schools, and we support Indian Point with electricity from sources yet to be many of the same causes. For example, our employer, developed. According to experts, without Indian Point Entergy, proudly supports the U.S. Chamber of air pollution would increase, our electricity costs would Commerce’s Hiring Our Heroes program, whose increase, and blackouts could occur. -

YON THOMAS Director of Photography Yonthomas.Com

YON THOMAS Director of Photography yonthomas.com COMMERCIAL & MUSIC VIDEO DIRECTORS Roman Coppola, Marc Klasfeld, Logan, The Malloys, Phil Harder, David Horowitz, thirtytwo, Phil Mucci, Marc Webb, Dean Karr, Barnaby Roper, Keir Yee, Kendall Bowlin, 3 Legged Legs, Jonathan Mannion, Mickey Finnegan, Doug Aitken, Charles Jensen, Will.I.Am, Geoff McFetridge, Vincent Haycock, Citizens of Tomorrow, Tony Petrossian, Umur Turagay, Steve Jocz, Ozan Aciktan, Melissa Silverman, Charles Richards, Dan Rush, Sarah Chatfield, Yutaka Sano, James Frost, Colourmovie, Anibal Suarez, Midori Ikematsu, Karina Taira, Alon Isocianu, Matt Lensky, Kevin de Freitas, Life Garland, Nzingha Stewart, AV Club, Angela Alvarado, Omer Fast, Ben Orisich, Nelson Cabrera, Adam Swaab, Brian Perkins, Elliot Lester, Craig Tanimoto, Jodeb, Canbert Yerguz, Anders Rostad Partial List COMMERCIALS Coca-Cola, BP, Canon, Target, AT&T, Avea, Gap, Ok Go Chevy Sonic*, Ok Go “All Is Not Lost”**, NOS Energy Drink, US State Department, KIA, Hewlett-Packard, Volvo, Honda, Ford Ranger/Escape, Vodaphone, MasterCard, NFL, Prada, Discover Card, ING Bank, 24-Hour Fitness, Showtime, Colorado Lottery, “Heroes” Promo, Virgin/USA, Tac, “Alien vs. Predator” DVD Promo, Colaturka, Opet, Kekstra, Genworth, Evilady, NBC, Atlas Jet Airways, Osu, Nike, Goodwrench Tires, Ece Chocolat, E Collect, Maille, Duo, Cartoon Network, X-Large, Noa, Ingrosso, Futuroscope, GSN, Kirin Beer, Amnesty International, Booster, Ohio Anti-Smoking PSA, Shop Boyz, Cape Cod Potato Chips, Signal, Amp’d Mobile, Sears, Iraq Ministry -

Frank's Chop Shop: Founded by Michael Malbon in New York City in 2006, Frank's Chop Shop Is a Lower East Side Neighborhood Staple to the Modern Gentleman of Leisure

-FRANK’S CHOP SHOP- NEW YORK’S BEST BARBER SHOP SINCE 2006 Frank's Chop Shop: Founded by Michael Malbon in New York City in 2006, Frank's Chop Shop is a Lower East Side neighborhood staple to the Modern Gentleman of Leisure. Acknowledging the great history of the American Barbershop, the Chop Shop features vintage 1930's barber chairs, classically trained barbers and utilizes straight razors, scissors as well as electric clippers. However, what truly sets Frank's Chop Shop apart is their dedication to serving as a hub of activity where patrons can swap stories, share new music, cut business deals, and enjoy coffee and a newspaper while having an expert cut and shave. It's this unique atmosphere and association that has attracted its diverse and loyal fanbase. Pictures from New York shop Kevin cutting Jonny Sweet Cheek (Top Right), Mr. Bee wiseman cuts Prodigy of MOBBDEEP (Left top) and few images. -Los Angeles- Los Angeles - Frank's Chop Shop, the premiere Lower East Side barbershop voted best barbershop by New York magazine several consecutive years in a row; is proud to announce the opening of a brand new Los Angeles location that doubles as a fully functional art gallery. The Los Angeles shop is a bold new move for the brand located in the heart of Hollywood on the infamous Melrose strip at 8209 Melrose Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90046. The 2000 sq. ft. shop will be a permanent fixture on the palm-lined street offering a one-of-a-kind experience for the distinguished "Modern Gentleman of Leisure" along with a selection of retail goods, men's grooming products, photography and fine art from the likes of Futura 2000, Jonathan Mannion, Gregory Siff, Block Photo, Harif Guzman, Saber, Ruslan Karablin, David Flores, Craig Wetherby, Estevan Oriol, Akira Ruiz, Keisha Baptiese, and many more. -

Hip-Hop's Future Finding Balance in Music and Life

CChicago Tribune | On TheTown | Section 5 | Friday, May23, 2014 13 ThePOP MUSICFaPREVIEWint and that sound of dark dance tunes By Jay Gentile | Special to the Tribune Nothing starts a party like Todd Fink. We spoke with Fink songs about death and paranoia. during a break in touring from Just ask The Faint, the synth rock Tallahassee, Fla., where he was post-punks who have been ex- quietly relaxing by the pool. Ex- porting their signature brand of cerpts from that conversation dark wave, nightmarish party follow: music for the better part of 15 years, long before a new genera- On the music’s perceived dark tion of kids draped themselves in sound: neon in order to first-bump to Most of the time, I have a hard techno beats at time finding a song dance music festivals that I want to sing across the country. When: 9 p.m. Friday with a happier melo- While the Omaha, Where: Metro, dy. I like tons of songs Neb., band has al- 3730 N. Clark St. that do it but when I ways been more of a do it, it doesn’t seem rock band than the Tickets: $25 (18+); like me. … Sometimes current crop of 773-549-4140 or metro we’ll think it would candy-coated elec- chicago.com be a fun juxtaposition tronic dance music to make a song overly contemporaries who dominate dark-sounding because of the the airwaves, there is no denying lyrical content or something like The Faint’s instrumental role in that. And those are usually the helping to remind bored-looking, ones that are the most misunder- cross-armed hipsters how to stood. -

The Economic Club of New York 113Th Year 573Rd Meeting LL COOL J Founder and Chief Exec

The Economic Club of New York 113th Year 573rd Meeting ________________________________________ LL COOL J Founder and Chief Executive Officer Rock the Bells ________________________________________ December 1, 2020 Webinar Moderator: Charles Phillips Trustee, The Economic Club of New York Managing Partner and Co-Founder, Recognize The Economic Club of New York – LL COOL J – December 1, 2020 Page 1 Introduction President Barbara Van Allen: Good afternoon. Thank you for joining us this afternoon. We are going to get started in exactly one minute. Thanks. Chairman John C. Williams Good afternoon everyone and welcome to the 573rd meeting of The Economic Club of New York, and this is our 113th year. I’m John Williams. I’m the Chairman of the Club and President and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The Economic Club of New York is the nation’s leading nonpartisan forum for discussions on economic, social and political issues. Before we begin, I’d like to thank our healthcare workers, our frontline workers and all of those in public positions that help make our lives safer and easier during this very difficult time. Our mission is as important today as ever as we continue to bring people together as a catalyst for conversation and innovation. Particularly during these challenging times, we proudly stand with all communities seeking inclusion and mutual understanding. To put those words into action, the Club kicked off its Focus on Racial Equity Series where we’ve been leveraging our platform to bring together prominent thought leaders to help us explore and better understand the various dimensions of racial inequity and highlight The Economic Club of New York – LL COOL J – December 1, 2020 Page 2 strategies, best practices and resources that the business community can use to be a force for change. -

250 Speakers Free Festival Register Today

Bulletin YOUR DAILY ENTERTAINMENT NEWS UPDATE MAY 10, 2021 Page 1 of 26 INSIDE DJ Khaled Lands Third • The Weeknd & Ariana Grande Hold Atop Hot 100; No. 1 Album on Billboard 200 Chart Billie Eilish, The Kid LAROI & Miley Cyrus With ‘Khaled Khaled’ Hit Top 10 BY KEITH CAULFIELD • TuneCore Owner Believe Begins IPO Process, J Khaled nets his third No. 1 album May 15-dated chart (where Khaled Khaled debuts at With Plans to on the Billboard 200 chart as Khaled No. 1) will be posted in full on Billboard’s website on Raise €500M Khaled debuts atop the list. May 11. For all chart news, follow @billboard and @ The 14-track album was released on billboardcharts on both Twitter and Instagram. • Streaming Prices, New Revenue & DApril 30 via We the Best/Epic Records and features Of Khaled Khaled’s 93,000 equivalent album units More: 5 Highlights a galaxy of guest stars, ranging from Drake and Jay- earned in the tracking week ending May 6, SEA units From WMG’s Z to Justin Timberlake and Justin Bieber. Khaled comprise 76,000 (equaling 106.87 million on-demand Earnings Call Khaled starts with 93,000 equivalent album units streams of the album’s tracks), album sales com- • ‘Vax Live’ Concert earned in the U.S. in the week ending May 6, accord- prise 14,000 and TEA units comprise 3,000. Khaled Raises $302 ing to MRC Data.Khaled Khaled follows DJ Khaled’s Khaled was preceded by a pair of top 10-charting Million, Exceeds previous leaders, Grateful (in 2017) and Major songs on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, both featuring Vaccine Goal Key (2016), both of which also boasted a bevy of A- Drake: “Popstar” and “Greece,” which reached Nos. -

Download Urban Legend Album Mp3 Urban Legend (T.I

download urban legend album mp3 Urban Legend (T.I. album) Urban Legend is the third studio album by American rapper T.I., released on November 30, 2004, through Grand Hustle Records and Atlantic Records. The album debuted at number seven on the Billboard 200, selling 193,000 copies in its first week of release, it charted at number one on the Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart, and at number one on the Top Rap Albums chart. The album's official lead single, "Bring Em Out", was released on October 19, 2004 and became his first top ten hit, peaking at number nine on the US Billboard Hot 100, while the second single "U Don't Know Me" peaked at number twenty-three on the Billboard Hot 100. His third single "ASAP" reached number 75 on the U.S. charts, number 18 on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs charts and number 14 on the Hot Rap Tracks. T.I. created a video for "ASAP"/"Motivation". However, "Motivation" only made it to number 62 on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart. The album features production provided by long time collaborating Producers DJ Toomp, Jazze Pha, Lil Jon, The Neptunes, Nick "Fury" Loftin, David Banner and Sanchez Holmes. New Producers to contribute to the album would inclued Daz Dillinger, Kevin "Khao" Cates, KLC, Mannie Fresh, Scott Storch and Swizz Beatz. Featured guests on the album would include Trick Daddy, Nelly, Lil Jon, B.G., Mannie Fresh, Daz Dillinger, Lil Wayne, Pharrell Williams, P$C, Jazze Pha and Lil' Kim. -

Digital Booklet

01 INTRO 02 LAX FILES 03 STATE OF EMERGENCY feat. Ice Cube 04 BULLETPROOF DIARIES feat. Raekwon 05 MY LIFE feat. Lil Wayne 06 MONEY 07 CALI SUNSHINE feat. Bilal 08 YA HEARD feat. Ludacris 09 HARD LIQUOR (INTERLUDE) 10 HOUSE OF PAIN 11 GENTLEMAN’S AFFAIR feat. Ne-Yo 12 LET US LIVE feat. Chrisette Michelle 13 TOUCHDOWN feat. Raheem DeVaughn 14 ANGEL feat. Common 15 NEVER CAN SAY GOODBYE feat. Latoya Williams 16 DOPE BOYS feat. Travis Barker 17 GAME’S PAIN feat. Keyshia Cole 18 LETTER TO THE KING feat. Nas 19 OUTRO thisizgame.com Geffen Records. 2220 Colorado Ave., comptongame.com Santa Monica, CA 90404. Manufactured and distributed in the United States myspace.com/thegame by Universal Music Distribution. p 2008 Geffen Records. All rights reserved. Unauthorized duplication is a violation of applicable laws. Bulletproof Diaries feat. Raekwon (J. Taylor, C. Woods, D. Drew) Produced by: Jellyroll ณ Published by: BabyGame/Sony ATV Songs LLC(BMI)PicoPride Intro Publishing(BMI)/Prince Jaibari (E. Simmons, E. Pope) Publishing(BMI)/Denver St. Publishing(BMI) Produced by: Ervin”EP” Pope ณ Prayer by: DMX Keyboards by: 1500 or Nothin’, Ervin “EP” Pope Recorded by: Geoff Gibbs @ Encore Studios, Bass Guitar: William “kiddFLYY” Taylor Burbank, CA ณ Mixed by: Steve “B” Baughman @ Recorded by: Geoff Gibbs at Encore Studios, Pacifique Studios, N. Hollywood, CA ณ As- Burbank, CA and Sam Kalandjian at Pacifique sisted by: Samuel Kalandjian & Chris Doremus Studios, N. Hollywood, CA ณ Mixed by: Steve “B” Baughman at Pacifique Studios, N. Hollywood, CA Assisted by: Samuel Kalandjian & Chris Doremus LAX Files (J.