Marvin Miller and Free Agency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family

Chapter One The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family The 1980–1985 Seasons ♦◊♦ As over forty-four thousand Pirates fans headed to Three Rivers Sta- dium for the home opener of the 1980 season, they had every reason to feel optimistic about the Pirates and Pittsburgh sports in general. In the 1970s, their Pirates had captured six divisional titles, two National League pennants, and two World Series championships. Their Steelers, after decades of futility, had won four Super Bowls in the 1970s, while the University of Pittsburgh Panthers led by Heisman Trophy winner Tony Dorsett added to the excitement by winning a collegiate national championship in football. There was no reason for Pittsburgh sports fans to doubt that the 1980s would bring even more titles to the City of Champions. After the “We Are Family” Pirates, led by Willie Stargell, won the 1979 World Series, the ballclub’s goals for 1980 were “Two in a Row and Two Million Fans.”1 If the Pirates repeated as World Series champions, it would mark the first time that a Pirates team had accomplished that feat in franchise history. If two million fans came out to Three Rivers Stadium to see the Pirates win back-to-back World Series titles, it would 3 © 2017 University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved. break the attendance record of 1,705,828, set at Forbes Field during the improbable championship season of 1960. The offseason after the 1979 World Series victory was a whirlwind of awards and honors, highlighted by World Series Most Valuable Player (MVP) Willie Stargell and Super Bowl MVP Terry Bradshaw of the Steelers appearing on the cover of the December 24, 1979, Sports Illustrated as corecipients of the magazine’s Sportsman of the Year Award. -

Ba Mss 100 Bl-2966.2001

GUIDE TO THE BOWIE K KUHN COLLECTION National Baseball Hall of Fame Library National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 www.baseballhall.org Collection Number BA MSS 100 BL-2966.2001 Title Bowie K Kuhn Collection Inclusive Dates 1932 – 1997 (1969 – 1984 bulk) Extent 48.2 linear feet (109 archival boxes) Repository National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 Abstract This is a collection of correspondence, meeting minutes, official trips, litigation files, publications, programs, tributes, manuscripts, photographs, audio/video recordings and a scrapbook relating to the tenure of Bowie Kent Kuhn as commissioner of Major League Baseball. Preferred Citation Bowie K Kuhn Collection, BA MSS 100, National Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum, Cooperstown, NY. Provenance This collection was donated to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by Bowie Kuhn in 1997. Kuhn’s system of arrangement and description was maintained. Access By appointment during regular business hours, email [email protected]. Property Rights This National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum owns the property rights to this collection. Copyright For information about permission to reproduce or publish, please contact the library. Processing Information This collection was processed by Claudette Scrafford, Manuscript Archivist and Catherine Mosher, summer student, between June 2010 and February 2012. Biography Bowie Kuhn was the Commissioner of Major League Baseball for three terms from 1969 to 1984. A lawyer by trade, Kuhn oversaw the introduction of free agency, the addition of six clubs, and World Series games played at night. Kuhn was born October 28, 1926, a descendant of famous frontiersman Jim Bowie. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Book Review: Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law J

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 8 Article 12 Issue 2 Spring Book Review: Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law J. Gordon Hylton Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation J. Gordon Hylton, Book Review: Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law, 8 Marq. Sports L. J. 455 (1998) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol8/iss2/12 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEWS LEGAL BASES: BASEBALL AND THE LAW Roger I. Abrams [Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Temple University Press 1998] xi / 226 pages ISBN: 1-56639-599-2 In spite of the greater popularity of football and basketball, baseball remains the sport of greatest interest to writers, artists, and historians. The same appears to be true for law professors as well. Recent years have seen the publication Spencer Waller, Neil Cohen, & Paul Finkelman's, Baseball and the American Legal Mind (1995) and G. Ed- ward White's, Creating the National Pastime: Baseball Transforms Itself, 1903-1953 (1996). Now noted labor law expert and Rutgers-Newark Law School Dean Roger Abrams has entered the field with Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law. Unlike the Waller, Cohen, Finkelman anthology of documents and White's history, Abrams does not attempt the survey the full range of intersections between the baseball industry and the legal system. In- stead, he focuses upon the history of labor-management relations. -

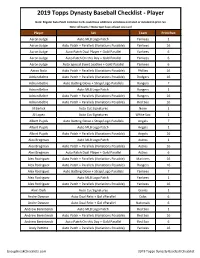

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball Checklist - Player

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball Checklist - Player Note: Regular Auto Patch Common Cards could have additional variations not listed or included in print run Note: All teams + None Spot have at least one card Player Set Team Print Run Aaron Judge Auto MLB Logo Patch Yankees 1 Aaron Judge Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Yankees 16 Aaron Judge Auto Patch Dual Player + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Judge Auto Patch On this Day + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Judge Auto Special Event Leather + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Nola Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Phillies 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Dodgers 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Rangers 7 Adrian Beltre Auto MLB Logo Patch Rangers 1 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Rangers 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Red Sox 16 Al Barlick Auto Cut Signatures None 1 Al Lopez Auto Cut Signatures White Sox 1 Albert Pujols Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Angels 7 Albert Pujols Auto MLB Logo Patch Angels 1 Albert Pujols Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Angels 16 Alex Bregman Auto MLB Logo Patch Astros 1 Alex Bregman Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Astros 16 Alex Bregman Auto Patch Dual Player + Gold Parallel Astros 6 Alex Rodriguez Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Mariners 16 Alex Rodriguez Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Rangers 16 Alex Rodriguez Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Yankees 7 Alex Rodriguez -

November 07 Retirees Newsletter

November 2007 Issue 3 Academic Year 2007-2008 Retirees Newsletter PROFESSIONAL STAFF CONGRESS CHAIRMAN’S REPORT: I thank Jim Perlstein for this colorful summary of Mr. Marvin Miller’s remarks. BALLPLAYERS AND UNIONISM: the standard player contract had MARVIN MILLER’S TALK amounted to serfdom. RESONATES WITH CUNY RETIREES Though young and inexperienced with unions, Miller found major Marvin Miller, retired leaguers to be fast learners Executive Director of the who quickly came to appreciate Major League’s Baseball their collective power through Players’ Association, collective action. The relatively provided the November small number of ballplayers meeting of the Retirees who make it to the major Chapter with a compelling leagues made it possible to retrospective on the origin and have regular one-on-one progress of baseball unionism since meetings with each player, in the 1960’s. addition to annual group meetings with each team during spring While some PSCers had looked training. And the union maintained forward to a nostalgic afternoon - an open door policy at its New York “Robin Roberts…I remember Robin headquarters so that players could Roberts” - Miller would have none of drop in during the season as their it. He kept his talk and his teams cycled through the city for responses to the numerous scheduled games. All of this, Miller questions focused on the nature of said, speeded the education unionism, particularly the question of process, kept members engaged unionism among celebrities and provided Miller and his small conditioned to see themselves as staff with the opportunity to hammer privileged independent contractors. home the idea that the members are And he stressed that ballplayers’ the union. -

Designated Hitters and Subesquent Team Scoring

DESIGNATED HITTERS AND SUBESQUENT TEAM SCORING PERFORMANCE IN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL A RESEARCH PAPER SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE BY SARAH E. CHO DR. HOLMES FINCH – ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY 2020 2 ABSTRACT RESEARCH PAPER: Designated Hitters and Subsequent Team Scoring Performance in Major League Baseball STUDENT: Sarah E. Cho DEGREE: Master of Science COLLEGE: Teachers College DATE: July 2020 PAGES: 27 The Designated Hitter (DH) rule in Major League Baseball (MLB) is a topic of great debate. In the National League (NL), all players take a turn at bat. However, in the American League (AL), a DH usually bats for the pitcher. MLB pitchers typically do not have strong batting averages. The DH rule was created to increase a team’s offense. This study looked at whether there is an apparent difference between the AL and the NL. In theory, a DH will lead to more hits, more runs, and therefore a higher scoring game. This study looked at the average runs per game and total home runs for the AL and NL during the 1998 through 2018 regular seasons. Since the assumptions of parametric multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) were not met, a nonparametric analysis was used. The permutation test for multivariate means results showed an apparent difference between the two leagues (p < .05). A quadratic discriminant analysis (QDA) was used as a follow up test and showed home runs as the variable driving the difference between the two leagues. Therefore, the AL has better scoring performance than the NL. -

Chicago Tribune: Baseball World Lauds Jerome

Baseball world lauds Jerome Holtzman -- chicagotribune.com Page 1 of 3 www.chicagotribune.com/sports/chi-22-holtzman-baseballjul22,0,5941045.story chicagotribune.com Baseball world lauds Jerome Holtzman Ex-players, managers, officials laud Holtzman By Dave van Dyck Chicago Tribune reporter July 22, 2008 Chicago lost its most celebrated chronicler of the national pastime with the passing of Jerome Holtzman, and all of baseball lost an icon who so graciously linked its generations. Holtzman, the former Tribune and Sun-Times writer and later MLB's official historian, indeed belonged to the entire baseball world. He seemed to know everyone in the game while simultaneously knowing everything about the game. Praise poured in from around the country for the Hall of Famer, from management and union, managers and players. "Those of us who knew him and worked with him will always remember his good humor, his fairness and his love for baseball," Commissioner Bud Selig said. "He was a very good friend of mine throughout my career in the game and I will miss his friendship and counsel. I extend my deepest sympathies to his wife, Marilyn, to his children and to his many friends." The men who sat across from Selig during labor negotiations—a fairly new wrinkle in the game that Holtzman became an expert at covering—remembered him just as fondly. "I saw Jerry at Cooperstown a few years ago and we talked old times well into the night," said Marvin Miller, the first executive director of the Players Association. "We always had a good relationship. He was a careful writer and, covering a subject matter he was not familiar with, he did a remarkably good job." "You don't develop the reputation he had by accident," said present-day union boss Donald Fehr. -

Want and Bait 11 27 2020.Xlsx

Year Maker Set # Var Beckett Name Upgrade High 1967 Topps Base/Regular 128 a $ 50.00 Ed Spiezio (most of "SPIE" missing at top) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 149 a $ 20.00 Joe Moeller (white streak btwn "M" & cap) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 252 a $ 40.00 Bob Bolin (white streak btwn Bob & Bolin) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 374 a $ 20.00 Mel Queen ERR (underscore after totals is missing) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 402 a $ 20.00 Jackson/Wilson ERR (incomplete stat line) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 427 a $ 20.00 Ruben Gomez ERR (incomplete stat line) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 447 a $ 4.00 Bo Belinsky ERR (incomplete stat line) 1968 Topps Base/Regular 400 b $ 800 Mike McCormick White Team Name 1969 Topps Base/Regular 47 c $ 25.00 Paul Popovich ("C" on helmet) 1969 Topps Base/Regular 440 b $ 100 Willie McCovey White Letters 1969 Topps Base/Regular 447 b $ 25.00 Ralph Houk MG White Letters 1969 Topps Base/Regular 451 b $ 25.00 Rich Rollins White Letters 1969 Topps Base/Regular 511 b $ 25.00 Diego Segui White Letters 1971 Topps Base/Regular 265 c $ 2.00 Jim Northrup (DARK black blob near right hand) 1971 Topps Base/Regular 619 c $ 6.00 Checklist 6 644-752 (cprt on back, wave on brim) 1973 Topps Base/Regular 338 $ 3.00 Checklist 265-396 1973 Topps Base/Regular 588 $ 20.00 Checklist 529-660 upgrd exmt+ 1974 Topps Base/Regular 263 $ 3.00 Checklist 133-264 upgrd exmt+ 1974 Topps Base/Regular 273 $ 3.00 Checklist 265-396 upgrd exmt+ 1956 Topps Pins 1 $ 500 Chuck Diering SP 1956 Topps Pins 2 $ 30.00 Willie Miranda 1956 Topps Pins 3 $ 30.00 Hal Smith 1956 Topps Pins 4 $ -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Manning, Jackson Snap USDESEA Marks

Page 26 THE STARS AND STRIPES Saturday, May 6, 1972 Manning, Jackson Snap USDESEA Marks By AUBREY ROBINSON old record ot 4:05.6 set last with Manning and Jackson was Arnolc to win the 100 meters son also jumped 5-8, but did it Staff Writer year by Bitburg's Bill Teasley. Munich's Dan Thomas, a by a half step. Both logged on his third try to finish third. MUNICH (S&S) — (Teasley won his 800-meter triple-winner who took firsts in times of 11.4 seconds. Anchorman Ron Baskin, Stuttgart's Tom Manning and heat in the Northern Regionals the 100 and 200 meters and the The fleet Thomas and about five vards behind when Heidelberg's George Jackson at Berlin, and was not sched- long jump. He placed second in Seymour staged duels in the he got the baton, turned in a cracked USDESEA records to uled for action in the 1500 until the 400 meters. 200 and 400 meters with blistering finish to bring Hei- highlight the 1972 Southern re- Saturday.) Jackson and Stuttgart's Sid Thomas taking the former in delberg victory in the 1600 gional prep track and field Stuttgart rode the strength of Seymour won two events each. 26.0 and Seymour the latter in meter relay. Jeff Weil, Bob championships here Friday. six firsts to capture Class A In the record-shattering per- 51.2. Montgomery and Daniels Manning, a senior, lowered team laurels with 69 points. formance of Manning, runner- Also winning the long jump teamed with Baskin for a time the standard for the 3200 Runnerup Heidelberg, which up Bob Montgomery of Heidel- with a leap of 21 feet, 1% of 3 minutes, 33.2 seconds to meters almost seven seconds had three firsts and five sec- berg also bettered the old 3200 inches, Thomas accounted for barely nip Karlsruhe at the in recording a time of 9 min- onds, totaled 48. -

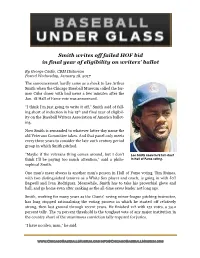

Smith Writes Off Failed HOF Bid in Final Year of Eligibility on Ballot

Smith writes off failed HOF bid in final year of eligibility on writers’ ballot By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Wednesday, January 18, 2017 The announcement hardly came as a shock to Lee Arthur Smith when the Chicago Baseball Museum called the for- mer Cubs closer with bad news a few minutes after the Jan. 18 Hall of Fame vote was announced. “I think I’m just going to write it off,” Smith said of fall- ing short of induction in his 15th and final year of eligibil- ity on the Baseball Writers Association of America ballot- ing. Now Smith is remanded to whatever latter-day name the old Veterans Committee takes. And that panel only meets every three years to consider the late 20th century period group in which Smith pitched. “Maybe if the veterans thing comes around, but I don’t Lee Smith knew he'd fall short think I’ll be paying too much attention,” said a philo- in Hall of Fame voting. sophical Smith. One man’s meat always is another man’s poison in Hall of Fame voting. Tim Raines, with two distinguished tenures as a White Sox player and coach, is going in with Jeff Bagwell and Ivan Rodriguez. Meanwhile, Smith has to take his proverbial glove and ball, and go home even after ranking as the all-time saves leader not long ago. Smith, working for many years as the Giants’ roving minor-league pitching instructor, has long stopped rationalizing the voting process in which he started off relatively strong, then lost ground through recent years.