The Effectiveness of a Computer-Assisted, Cognitive-Behavior Program for Treating Anxiety Symptoms in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder" (2015)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Front Page First Opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, It Was Instantly Heralded As a Classic

SUPPORT FOR THE 2019 SEASON OF THE FESTIVAL THEATRE IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY DANIEL BERNSTEIN AND CLAIRE FOERSTER PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY NONA MACDONALD HEASLIP 2 DIRECTOR’S NOTES SCAVENGING FOR THE TRUTH BY GRAHAM ABBEY “Were it left to me to decide between a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.” – Thomas Jefferson, 1787 When The Front Page first opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, it was instantly heralded as a classic. Nearly a century later, this iconic play has retained its place as one of the great American stage comedies of all time. Its lasting legacy stands as a testament to its unique DNA: part farce, part melodrama, with a healthy dose of romance thrown into the mix, The Front Page is at once a veneration and a reproof of the gritty, seductive world of Chicago journalism, firmly embedded in the freewheeling euphoria of the Roaring Twenties. According to playwrights (and former Chicago reporters) Charles MacArthur and Ben Hecht, the play allegedly found its genesis in two real-life events: a practical joke carried out on MacArthur as he was heading west on a train with his fiancée, and the escape and disappearance of the notorious gangster “Terrible” Tommy consuming the conflicted heart of a city O’Conner four days before his scheduled caught in the momentum of progress while execution at the Cook County Jail. celebrating the underdogs who were lost in its wake. O’Conner’s escape proved to be a seminal moment in the history of a city struggling Chicago’s metamorphosis through the to find its identity amidst the social, cultural “twisted twenties” is a paradox in and of and industrial renaissance of the 1920s. -

Downloads, and Weekly Attendees

riscilla apersVol 32, No 4 | Autumn 2018 PPThe academic journal of CBE International Social Sciences 3 Muted Group Theory: A Tool for Hearing Marginalized Voices Linda Lee Smith Barkman 8 The Importance of Age Norms When Considering Gender Issues Jason Eden and Naomi Eden 14 Christian Women’s Beliefs on Female Subordination and Male Authority Susan H. Howell and Kristyn Duncan 15 The Experiences of Women in Church and Denominational Leadership Susan H. Howell and Ariel Thompson 18 Marriage Ideology and Decision-Making Susan H. Howell, Bethany G. Lester, Alayna N. Owens 23 The Delight of Daughters: A Theology of Daughterhood Beulah Wood 29 Book Review: Biblical Porn: Affect, Labor, and Pastor Mark Driscoll’s Evangelical Empire by Jessica Johnson Jamin Hübner Priscilla and Aquila instructed Apollos more perfectly in the way of the Lord. (Acts 18:26) I Tertius . that made you fight to stay awake. It was the art (or lack thereof) of communication, which is a social science. Psychology and sociology, ethnography Consider counseling, a profession and skill set which and ethnology, political science and arises primarily from psychology. A Christian counselor economics. These and other social will approach psychology, and therefore counseling, with sciences are tools for understanding a certain set of theological beliefs. To give a final example, the people of the world—as individuals, Bible translation—surely an endeavor that underlies almost as families, as groups, as cultures and all biblical interpretation—happens at the intersection of subcultures. The articles in this issue of biblical studies and human language. And, of course, the Priscilla Papers all arise, directly or indirectly, from one or study of language (linguistics) and of the cultures that more social sciences. -

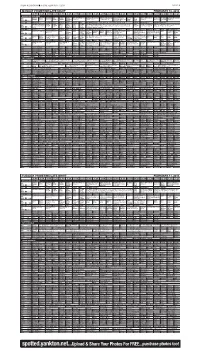

Spotted.Yankton.Net...Upload & Share Your Photos for FREE...Purchase

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 7, 2014 PAGE 9B MONDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT FEBRUARY 10, 2014 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Curious Arthur Å WordGirl Wild Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow Independent Lens The Red BBC Charlie Rose (N) (In Tavis Smi- The Mind Antiques Roadshow PBS George (DVS) Å (DVS) Kratts Å Speaks Business Stereo) Å “Detroit” (N) Å “Eugene, OR” Å Mississippi agency and Green World Stereo) Å ley (N) Å of a Chef “Detroit” Å KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report civil rights. (N) Show News Å KTIV $ 4 $ XXII Olympics Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent XXII Winter Olympics Alpine Skiing, Freestyle Skiing, Short Track. Å News 4 XXII Olympics XXII Winter Olympics XXII Winter Olympics Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big XXII Winter Olympics Alpine Skiing, Freestyle Skiing, Short Track. From Sochi, KDLT XXII Winter Olympics XXII Winter Olympics Alpine Skiing, Freestyle NBC Speed Skating, Biath- Judy Å Judy Å News Nightly News Bang Russia. Alpine skiing: women’s super combined; freestyle skiing; short track. (N News Å Short Track, Luge. Å Skiing, Short Track. (In Stereo) Å KDLT % 5 % lon. Å (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory Same-day Tape) (In Stereo) Å KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. Phil Å The Dr. Oz Show News at ABC News Inside The Bachelor (N) (In Stereo) Å Castle “Valkyrie” News Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline Paid Inside ABC World News Dr. -

SBR Media Catalog of Works Genre: Romance

SBR Media Catalog of Works Genre: Romance This catalog features the novels available for foreign translation and audio rights purchases. SBR Media is owned by Stephanie Phillips Contact: [email protected] Phone: 843.421.7570 SBR Media 3761 Renee Dr. Suite #223 Myrtle Beach, SC 29526 The information in this catalog is accurate as of July 29, 2020. Clients, titles, and availability should be confirmed. SBR Media Catalog of Works .................................................................................................................... 1 Alexis Noelle ............................................................................................................................................... 14 Her Series : Contemporary Suspense ...................................................................................................... 14 Keeping Her ......................................................................................................................................... 14 Deathstalkers MC Series : Contemporary Suspense ............................................................................... 15 Corrupted ............................................................................................................................................. 15 Shattered Series : Contemporary Suspense ............................................................................................. 15 Shattered Innocence ............................................................................................................................ -

Animal Traffic: Making, Remaking, and Unmaking Commodities in Global Live Wildlife Trade

ANIMAL TRAFFIC: MAKING, REMAKING, AND UNMAKING COMMODITIES IN GLOBAL LIVE WILDLIFE TRADE by ROSEMARY-CLAIRE MAGDELEINE SOLANGE COLLARD A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Geography) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Rosemary-Claire Magdeleine Solange Collard, 2013 Abstract Against mass species loss and escalating concern over declining biodiversity, legal and illegal trade in wildlife is booming. Annually, it generates tens of billions of dollars and involves the circulation of billions of live and dead animals worldwide. This dissertation examines one dimension of this economy: flows of live, wild-caught animals – namely exotic pets – into North America. My central questions are: how are wild animals’ lives and bodies transformed into commodities that circulate worldwide and can be bought and owned? How are these commodities remade and even unmade? In answering these questions the dissertation is concerned not only with embodied practices, but also with broader, dominant assumptions about particular figures of the human and the animal, and the relations between them. This dissertation draws on reading across economic geography and sociology, political economy and ecology, and political theory to construct a theoretical approach with three strands: a commodity chain framework, a theory of performativity, and an anti-speciesist position. It weaves this theoretical grounding through multi-sited -

Illuminations

Illuminations A magazine of student, faculty, and staff creative expression Volume 9 – 2007 Southeast Community College 1 We offer special thanks to the students, faculty, and staff who submitted works for consideration. Rights revert to the author after publication in Illuminations. The content of this magazine does not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff or the Academic Education Division and the Visual Publications Program of Southeast Community College. The content reflects student, faculty, and staff work without censorship by the editorial staff. ©2007 2 The Illuminations Team Editorial Team: Heather Barnes, Renae Blum, Maddie Bromwich, Vanessa Buck, Ella Durham, Lacey Mason, Kara Rabe, Daniel Violin, Art Ortiz Project Coordinators: Kimberly Fangman, Mike Keating, Rebecca Orsini Project Assistants: Rebecca Burt, Beth Deinert, Julie MacDonald, Rachel Mason, Merrill Peterson, Bang Tran, Pat Underwood, the LRC staffs Visual Publications Team: Shane Besch, Ashley Frank, Danielle Hostetler, Ashly Lannin, Andrea Meyer, Mercedes Meza, Chrisopher Rigoni, John Schuff, Regina Stauffer. A special thank you to our printers: Lisa Vosta, Kristine Meek, Brian Piontek Cover illustration by Tanner Peregrine 3 My War – Our War (The Husband’s View) ...................................9 Jeremiah D. Behrends My War – Our War (The Wife’s View) ........................................11 Jamie L. Behrends Keep an Eye on Summer ..............................................................14 Carolee Ritter Some Days....................................................................................15 -

How the Particle Fever Team Made a Physics Thriller Theory Via Stunning Animations

NOVEMBERNOVEMBER / DECEMBER 1313 SCIENCE IN FOCUS How the Particle Fever team made a physics thriller US $7.95 USD Canada $8.95 CDN Int’l $9.95 USD G<ID@KEF%+*-* 9L==8CF#EP L%J%GFJK8><G8@; 8LKF ALSO: INSIDE THE SQUARE | CRAFTING GLOBAL CONTENT GIJIKJK; A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. RRealscreenealscreen Cover.inddCover.indd 3 006/11/136/11/13 112:182:18 PPMM COUNTING CARS® ©2013 A&E Television Networks, LLC. All rights reserved. 1530-14-A. reserved. All rights LLC. Networks, Television A&E ©2013 RODEO GIRLS™ DANCE MOMS® DUCK DYNASTY® ALWAYS ENTERTAINING The most original entertainment lives on our networks. THE LEGEND OF SHELBY THE SWAMP MAN™ PROJECT RUNWAY RRS.23977.AE.inddS.23977.AE.indd 1 008/11/138/11/13 22:28:28 PPMM contents november / december 13 BBC Worldwide’s Million Dollar Intern is moving 13 internationally. BIZ 19 Brands, producers and networks converge on BCON Expo; exec shuffl es at NBCU cable nets ................................9 Director Jehane Noujaim’s doc The Square, recently acquired by Netfl ix, enjoyed two world premieres. AUDIENCE & STRATEGY Crafting global content for international network groups ..................13 “A lot of programs these IDEAS AND EXECUTION Behind the scenes of The Square ........................................................19 days are about celebs going on a ‘life journey,’ SPECIAL REPORT cryin’ at the end of it… SCIENCE FOCUS An exploration of four scintillating science-based projects .................24 This is not that sort of FORMAT FOCUS program.” 30 Syfy going live with Opposite Worlds ..................................................28 AND ONE MORE THING NOVEMBERNOVEMBER / DECEMBER 1313 on the cover F***in’ hell, it’s Karl Pilkington! .........................................................30 Design fi rm MK12 collaborated with SCIENCE the fi lmmakers of the feature doc IN FOCUS Particle Fever to help explain particle How the Particle Fever team made a physics thriller theory via stunning animations. -

Party Polarization and Its Effects on the American Electorate in The

THE PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ALGERIA MINISTRY OF HIGHER EDUCATION AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH MENTOURI UNIVERSITY, CONSTANTINE FACULTY OF LETTERS AND LANGUAGES DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES/ENGLISH A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of MAGISTER in AMERICAN HISTORY AND POLITICS Party Polarization and its Effects on the American Electorate in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries Jury: Candidate: President: Dr HAROUNI Brahim, University of Constantine Mrs BENSACI Supervisor: Dr KIBECHE Abdelkrim, University of Constantine HARBI Hayette Examiner: Dr BENDJADOU Yazid, University of Annaba Examiner: M. MEGHERBI Nasreddine, University of Constantine January 2008 Acknowledgements At the outset, I have to express my sincere gratitude to Allah. Without the help of Almighty Allah, this dissertation would never have materialised. I am deeply indebted to my family who has been a source of reassurance and strength throughout the whole research process. Above all, my deepest recognition goes to my husband for his support to me and his patience. I am likewise immensely grateful to the jury members who accepted to read and appraise this paper. I similarly thank Professor Kibeche Abdedlkrim who accepted to supervise this work, Dr Harouni Brahim who was an immeasurable source of insightful guidance and advice and Mrs Mammeri Fatima who kept believing in me and encouraged me. I appreciated their generous assistance and their constructive suggestions made at various stages of the research. Also, I take this opportunity to express thank to all the staff that have taught and trained me throughout all the levels of my education. Special thanks are conveyed to former head of the department Mr Nemouchi Abdelhak who has done me favours on several occasions. -

One-Stop Shopping at Swampscott Town Hall Restaurateur Aiming for Uncommon Success

SATURDAY, JANUARY 4, 2020 COURTESY PHOTO From left, town employee Chrissy Raposo, assistant town administra- PHOTO | PAUL HALLORAN tor Ronald Mendes, and employees Diane Folan and Elana Berube pro- Uncommon Feasts owner Michelle Mulford and restaurant employee vide assistance to a town resident in the new customer service of ce at Paula Agganis prepare food in their Lydia Pinkham building location. Swampscott Town Hall. Restaurateur aiming One-stop shopping at for Uncommon success Swampscott Town Hall By Paul Halloran The hallmark of the restaurant, Mul- By Steve Krause at Town Hall. FOR THE ITEM ford said, is that she uses locally grown ITEM STAFF The new of ce is called Town Hall food as much as possible and everything Custom Service, and it is situated, said If you cook it, they will come – and that is served is made on site. In 2020 SWAMPSCOTT — The people in Mendes, to assist taxpayers with assess- hopefully stay around to enjoy the am- she plans to focus more on dinners in the Swampscott have always been proud of ing and payment questions, along with bience. restaurant and launch a lunch delivery their Town Hall for its attentiveness to other inquiries such as trash/recycling, That philosophy is what prompted service. its history. vital statistics, voter registration and Michelle Mulford to parlay her catering If Milford had any doubts that her idea The one-time home to General Electric new resident issues. business – which she moved to the Lyd- was is a good one, they were eliminat- founder Elihu Thomson contains much “To begin with, the of ce started off as ia Pinkham building last May – into a ed by two incidents on the same day in of the architecture and ambiance that being the Town Clerk and Tax Collec- restaurant that offers breakfast, lunch December. -

Entertainment EXTRA! March 5 - 11, 2020 Has a New Home at the LINKS! 1361 S

$10 OFF $10 OFF WELLNESS MEMBERSHIP MICROCHIP New Clients Only All locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Expires 3/31/2020 Expires 3/31/2020 Free First Office Exams FREE EXAM Extended Hours Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Multiple Locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. www.forevervets.com Expires 3/31/2020 4 x 2” ad Your Community Voice for 50 Years RecorPONTE VEDRA der entertainment EXTRA! March 5 - 11, 2020 has a new home at THE LINKS! 1361 S. 13th Ave., Ste. 140 Jacksonville Beach Offering: · Hydrafacials · RF Microneedling A rallies · Body Contouring · B12 Complex / around a friend and his loved ones Lipolean Injections Michael O’Neill, J. August Richards, Sarah Wayne Callies and Clive Standen (from left) Get Skinny with it! star in “Council of Dads,” premiering Tuesday on NBC. (904) 999-0977 1 x 5” ad www.SkinnyJax.com Now is a great time to It will provide your home: Kathleen Floryan List Your Home for Sale • Complimentary coverage while REALTOR® Broker Associate the home is listed • An edge in the local market LIST IT because buyers prefer to purchase a home that a seller stands behind • Reduced post-sale liability with WITH ME! ListSecure® I will provide you a FREE America’s Preferred 904-687-5146 Home Warranty for [email protected] your home when we put www.kathleenfloryan.com it on the market. 4 x 3” ad BY JAY BOBBIN NBC’s What’s Available NOW pulls together for an ill friend’s family Some friends promise to be there for for its first several weeks. -

06 01-21-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday,January 21, 2014 Monday Evening January 27, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Bachelor Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, JAN. 24 THROUGH THURSDAY, JAN. 30 KBSH/CBS How I Met 2 Broke G Mike Mom Intelligence Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC Hollywood Game Night Hollywood Game Night The Blacklist Local Tonight Show w/Leno J. Fallon FOX The Following The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Bad Ink Bad Ink Mayne Mayne Mayne Mayne Duck D. Duck D. AMC The Green Mile Twister ANIM Finding Bigfoot Gator Boys Beaver Beaver Finding Bigfoot Gator Boys CNN Anderson Cooper 360 Piers Morgan Live AC 360 Later E. B. OutFront Piers Morgan Live DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Rods N' Wheels Fast N' Loud Rods N' Wheels DISN Good Luck Let It Shine Good Luck Austin ANT Farm Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News Fashion Police Kardashian Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN College Basketball College Basketball SportsCenter SportsCenter ESPN2 Wm. Basketball Wm. Basketball Olbermann Olbermann FAM Switched at Birth The Fosters The Fosters The 700 Club Switched at Birth FX Frnds-Benefits Archer Chozen Archer Chozen Chozen Archer HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunt Intl Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Pawn Pawn Swamp People Pawn Pawn Pawn Pawn Pawn Pawn LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Teen Wolf Teen Wolf Teen Wolf Teen Wolf Teen Wolf I, Robot NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Lost Girl Being Human Bitten Lost Girl Being Human For your SPIKE Law Abiding Citizen Alpha Dog TBS Fam. -

David Hicks, Tetum-Ghosts-And-Kin-Fertility-And-Gender-In-East-Timor

r Tefum Sfiosís Rin David Hicks State University ofNew York, Stony Brook WAVELAKD P R E SS, IN< Prospect Heights, Illinois í For information about this book, write or cali: Waveland Press, Inc. P.O. Box 400 Prospect Heights, Illinois 60070 (708) 634-0081 To my wife, Maxine Copyright © 1976 by David Hicks 1988 reissued by Waveland Press, Inc. ISBN 0-88133-320-4 All ríghts reservM. N$gart o f this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval System, or transmiite'a in any form or by any means without permission in writing fróm the publisher. Printéd in the United States of America 7 6 5 4 Confettis Acknowledgements v Editors’ preface vii 1 Fieldwork 1 2 Birth: The cycle opens 19 3 Ecology 3 8 4 The house 56 5 Kin and affines 67 6 Marriage 85 7 Death: The cycle closes 107 Glossary ot Tetum words 127 List of anthropological terms 131 Recommended readings 133 Bibliography 135 Index 137 Achnoroledgemenfs Besides those Caraubalo villagers mentioned in the following chapters, I wish to thank those villagers whose ñames do not appear but without whose help my field research would have been impossible, and the following individuáis and institutions for their assistance: the late Professor Sir Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard, Professor Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf, Dr. Ravi Jain, Professor H. G. Schulte Nordholt, Dr. Barbara Ward, Mr. Ruy Cinatti, Dr. José Teles, Mr. John Burton, the Junta de Investigares do Ultramar, and the Frederick Soddy Trust. My fieldwork was made possible by a grant from the London Committee of the London-Cornell Project for East and Southeast Asian Studies which was supported jointly by the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Nuffield Foundation.