The Mythopoetics of Shakespeare's Warrior Queens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Front Page First Opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, It Was Instantly Heralded As a Classic

SUPPORT FOR THE 2019 SEASON OF THE FESTIVAL THEATRE IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY DANIEL BERNSTEIN AND CLAIRE FOERSTER PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY NONA MACDONALD HEASLIP 2 DIRECTOR’S NOTES SCAVENGING FOR THE TRUTH BY GRAHAM ABBEY “Were it left to me to decide between a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.” – Thomas Jefferson, 1787 When The Front Page first opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, it was instantly heralded as a classic. Nearly a century later, this iconic play has retained its place as one of the great American stage comedies of all time. Its lasting legacy stands as a testament to its unique DNA: part farce, part melodrama, with a healthy dose of romance thrown into the mix, The Front Page is at once a veneration and a reproof of the gritty, seductive world of Chicago journalism, firmly embedded in the freewheeling euphoria of the Roaring Twenties. According to playwrights (and former Chicago reporters) Charles MacArthur and Ben Hecht, the play allegedly found its genesis in two real-life events: a practical joke carried out on MacArthur as he was heading west on a train with his fiancée, and the escape and disappearance of the notorious gangster “Terrible” Tommy consuming the conflicted heart of a city O’Conner four days before his scheduled caught in the momentum of progress while execution at the Cook County Jail. celebrating the underdogs who were lost in its wake. O’Conner’s escape proved to be a seminal moment in the history of a city struggling Chicago’s metamorphosis through the to find its identity amidst the social, cultural “twisted twenties” is a paradox in and of and industrial renaissance of the 1920s. -

Transantiquity

TransAntiquity TransAntiquity explores transgender practices, in particular cross-dressing, and their literary and figurative representations in antiquity. It offers a ground-breaking study of cross-dressing, both the social practice and its conceptualization, and its interaction with normative prescriptions on gender and sexuality in the ancient Mediterranean world. Special attention is paid to the reactions of the societies of the time, the impact transgender practices had on individuals’ symbolic and social capital, as well as the reactions of institutionalized power and the juridical systems. The variety of subjects and approaches demonstrates just how complex and widespread “transgender dynamics” were in antiquity. Domitilla Campanile (PhD 1992) is Associate Professor of Roman History at the University of Pisa, Italy. Filippo Carlà-Uhink is Lecturer in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Exeter, UK. After studying in Turin and Udine, he worked as a lecturer at the University of Heidelberg, Germany, and as Assistant Professor for Cultural History of Antiquity at the University of Mainz, Germany. Margherita Facella is Associate Professor of Greek History at the University of Pisa, Italy. She was Visiting Associate Professor at Northwestern University, USA, and a Research Fellow of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation at the University of Münster, Germany. Routledge monographs in classical studies Menander in Contexts Athens Transformed, 404–262 BC Edited by Alan H. Sommerstein From popular sovereignty to the dominion -

The General Stud Book : Containing Pedigrees of Race Horses, &C

^--v ''*4# ^^^j^ r- "^. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/generalstudbookc02fair THE GENERAL STUD BOOK VOL. II. : THE deiterol STUD BOOK, CONTAINING PEDIGREES OF RACE HORSES, &C. &-C. From the earliest Accounts to the Year 1831. inclusice. ITS FOUR VOLUMES. VOL. II. Brussels PRINTED FOR MELINE, CANS A.ND C"., EOILEVARD DE WATERLOO, Zi. M DCCC XXXIX. MR V. un:ve PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. To assist in the detection of spurious and the correction of inaccu- rate pedigrees, is one of the purposes of the present publication, in which respect the first Volume has been of acknowledged utility. The two together, it is hoped, will form a comprehensive and tole- rably correct Register of Pedigrees. It will be observed that some of the Mares which appeared in the last Supplement (whereof this is a republication and continua- tion) stand as they did there, i. e. without any additions to their produce since 1813 or 1814. — It has been ascertained that several of them were about that time sold by public auction, and as all attempts to trace them have failed, the probability is that they have either been converted to some other use, or been sent abroad. If any proof were wanting of the superiority of the English breed of horses over that of every other country, it might be found in the avidity with which they are sought by Foreigners. The exportation of them to Russia, France, Germany, etc. for the last five years has been so considerable, as to render it an object of some importance in a commercial point of view. -

Downloads, and Weekly Attendees

riscilla apersVol 32, No 4 | Autumn 2018 PPThe academic journal of CBE International Social Sciences 3 Muted Group Theory: A Tool for Hearing Marginalized Voices Linda Lee Smith Barkman 8 The Importance of Age Norms When Considering Gender Issues Jason Eden and Naomi Eden 14 Christian Women’s Beliefs on Female Subordination and Male Authority Susan H. Howell and Kristyn Duncan 15 The Experiences of Women in Church and Denominational Leadership Susan H. Howell and Ariel Thompson 18 Marriage Ideology and Decision-Making Susan H. Howell, Bethany G. Lester, Alayna N. Owens 23 The Delight of Daughters: A Theology of Daughterhood Beulah Wood 29 Book Review: Biblical Porn: Affect, Labor, and Pastor Mark Driscoll’s Evangelical Empire by Jessica Johnson Jamin Hübner Priscilla and Aquila instructed Apollos more perfectly in the way of the Lord. (Acts 18:26) I Tertius . that made you fight to stay awake. It was the art (or lack thereof) of communication, which is a social science. Psychology and sociology, ethnography Consider counseling, a profession and skill set which and ethnology, political science and arises primarily from psychology. A Christian counselor economics. These and other social will approach psychology, and therefore counseling, with sciences are tools for understanding a certain set of theological beliefs. To give a final example, the people of the world—as individuals, Bible translation—surely an endeavor that underlies almost as families, as groups, as cultures and all biblical interpretation—happens at the intersection of subcultures. The articles in this issue of biblical studies and human language. And, of course, the Priscilla Papers all arise, directly or indirectly, from one or study of language (linguistics) and of the cultures that more social sciences. -

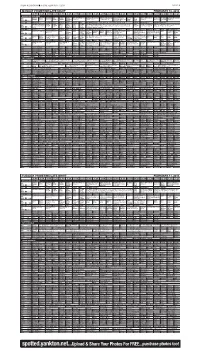

Spotted.Yankton.Net...Upload & Share Your Photos for FREE...Purchase

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 7, 2014 PAGE 9B MONDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT FEBRUARY 10, 2014 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Curious Arthur Å WordGirl Wild Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow Independent Lens The Red BBC Charlie Rose (N) (In Tavis Smi- The Mind Antiques Roadshow PBS George (DVS) Å (DVS) Kratts Å Speaks Business Stereo) Å “Detroit” (N) Å “Eugene, OR” Å Mississippi agency and Green World Stereo) Å ley (N) Å of a Chef “Detroit” Å KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report civil rights. (N) Show News Å KTIV $ 4 $ XXII Olympics Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent XXII Winter Olympics Alpine Skiing, Freestyle Skiing, Short Track. Å News 4 XXII Olympics XXII Winter Olympics XXII Winter Olympics Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big XXII Winter Olympics Alpine Skiing, Freestyle Skiing, Short Track. From Sochi, KDLT XXII Winter Olympics XXII Winter Olympics Alpine Skiing, Freestyle NBC Speed Skating, Biath- Judy Å Judy Å News Nightly News Bang Russia. Alpine skiing: women’s super combined; freestyle skiing; short track. (N News Å Short Track, Luge. Å Skiing, Short Track. (In Stereo) Å KDLT % 5 % lon. Å (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory Same-day Tape) (In Stereo) Å KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. Phil Å The Dr. Oz Show News at ABC News Inside The Bachelor (N) (In Stereo) Å Castle “Valkyrie” News Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline Paid Inside ABC World News Dr. -

SBR Media Catalog of Works Genre: Romance

SBR Media Catalog of Works Genre: Romance This catalog features the novels available for foreign translation and audio rights purchases. SBR Media is owned by Stephanie Phillips Contact: [email protected] Phone: 843.421.7570 SBR Media 3761 Renee Dr. Suite #223 Myrtle Beach, SC 29526 The information in this catalog is accurate as of July 29, 2020. Clients, titles, and availability should be confirmed. SBR Media Catalog of Works .................................................................................................................... 1 Alexis Noelle ............................................................................................................................................... 14 Her Series : Contemporary Suspense ...................................................................................................... 14 Keeping Her ......................................................................................................................................... 14 Deathstalkers MC Series : Contemporary Suspense ............................................................................... 15 Corrupted ............................................................................................................................................. 15 Shattered Series : Contemporary Suspense ............................................................................................. 15 Shattered Innocence ............................................................................................................................ -

Animal Traffic: Making, Remaking, and Unmaking Commodities in Global Live Wildlife Trade

ANIMAL TRAFFIC: MAKING, REMAKING, AND UNMAKING COMMODITIES IN GLOBAL LIVE WILDLIFE TRADE by ROSEMARY-CLAIRE MAGDELEINE SOLANGE COLLARD A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Geography) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Rosemary-Claire Magdeleine Solange Collard, 2013 Abstract Against mass species loss and escalating concern over declining biodiversity, legal and illegal trade in wildlife is booming. Annually, it generates tens of billions of dollars and involves the circulation of billions of live and dead animals worldwide. This dissertation examines one dimension of this economy: flows of live, wild-caught animals – namely exotic pets – into North America. My central questions are: how are wild animals’ lives and bodies transformed into commodities that circulate worldwide and can be bought and owned? How are these commodities remade and even unmade? In answering these questions the dissertation is concerned not only with embodied practices, but also with broader, dominant assumptions about particular figures of the human and the animal, and the relations between them. This dissertation draws on reading across economic geography and sociology, political economy and ecology, and political theory to construct a theoretical approach with three strands: a commodity chain framework, a theory of performativity, and an anti-speciesist position. It weaves this theoretical grounding through multi-sited -

Illuminations

Illuminations A magazine of student, faculty, and staff creative expression Volume 9 – 2007 Southeast Community College 1 We offer special thanks to the students, faculty, and staff who submitted works for consideration. Rights revert to the author after publication in Illuminations. The content of this magazine does not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff or the Academic Education Division and the Visual Publications Program of Southeast Community College. The content reflects student, faculty, and staff work without censorship by the editorial staff. ©2007 2 The Illuminations Team Editorial Team: Heather Barnes, Renae Blum, Maddie Bromwich, Vanessa Buck, Ella Durham, Lacey Mason, Kara Rabe, Daniel Violin, Art Ortiz Project Coordinators: Kimberly Fangman, Mike Keating, Rebecca Orsini Project Assistants: Rebecca Burt, Beth Deinert, Julie MacDonald, Rachel Mason, Merrill Peterson, Bang Tran, Pat Underwood, the LRC staffs Visual Publications Team: Shane Besch, Ashley Frank, Danielle Hostetler, Ashly Lannin, Andrea Meyer, Mercedes Meza, Chrisopher Rigoni, John Schuff, Regina Stauffer. A special thank you to our printers: Lisa Vosta, Kristine Meek, Brian Piontek Cover illustration by Tanner Peregrine 3 My War – Our War (The Husband’s View) ...................................9 Jeremiah D. Behrends My War – Our War (The Wife’s View) ........................................11 Jamie L. Behrends Keep an Eye on Summer ..............................................................14 Carolee Ritter Some Days....................................................................................15 -

Euripides and Gender: the Difference the Fragments Make

Euripides and Gender: The Difference the Fragments Make Melissa Karen Anne Funke A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Ruby Blondell, Chair Deborah Kamen Olga Levaniouk Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2013 Melissa Karen Anne Funke University of Washington Abstract Euripides and Gender: The Difference the Fragments Make Melissa Karen Anne Funke Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Ruby Blondell Department of Classics Research on gender in Greek tragedy has traditionally focused on the extant plays, with only sporadic recourse to discussion of the many fragmentary plays for which we have evidence. This project aims to perform an extensive study of the sixty-two fragmentary plays of Euripides in order to provide a picture of his presentation of gender that is as full as possible. Beginning with an overview of the history of the collection and transmission of the fragments and an introduction to the study of gender in tragedy and Euripides’ extant plays, this project takes up the contexts in which the fragments are found and the supplementary information on plot and character (known as testimonia) as a guide in its analysis of the fragments themselves. These contexts include the fifth- century CE anthology of Stobaeus, who preserved over one third of Euripides’ fragments, and other late antique sources such as Clement’s Miscellanies, Plutarch’s Moralia, and Athenaeus’ Deipnosophistae. The sections on testimonia investigate sources ranging from the mythographers Hyginus and Apollodorus to Apulian pottery to a group of papyrus hypotheses known as the “Tales from Euripides”, with a special focus on plot-type, especially the rape-and-recognition and Potiphar’s wife storylines. -

How the Particle Fever Team Made a Physics Thriller Theory Via Stunning Animations

NOVEMBERNOVEMBER / DECEMBER 1313 SCIENCE IN FOCUS How the Particle Fever team made a physics thriller US $7.95 USD Canada $8.95 CDN Int’l $9.95 USD G<ID@KEF%+*-* 9L==8CF#EP L%J%GFJK8><G8@; 8LKF ALSO: INSIDE THE SQUARE | CRAFTING GLOBAL CONTENT GIJIKJK; A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. RRealscreenealscreen Cover.inddCover.indd 3 006/11/136/11/13 112:182:18 PPMM COUNTING CARS® ©2013 A&E Television Networks, LLC. All rights reserved. 1530-14-A. reserved. All rights LLC. Networks, Television A&E ©2013 RODEO GIRLS™ DANCE MOMS® DUCK DYNASTY® ALWAYS ENTERTAINING The most original entertainment lives on our networks. THE LEGEND OF SHELBY THE SWAMP MAN™ PROJECT RUNWAY RRS.23977.AE.inddS.23977.AE.indd 1 008/11/138/11/13 22:28:28 PPMM contents november / december 13 BBC Worldwide’s Million Dollar Intern is moving 13 internationally. BIZ 19 Brands, producers and networks converge on BCON Expo; exec shuffl es at NBCU cable nets ................................9 Director Jehane Noujaim’s doc The Square, recently acquired by Netfl ix, enjoyed two world premieres. AUDIENCE & STRATEGY Crafting global content for international network groups ..................13 “A lot of programs these IDEAS AND EXECUTION Behind the scenes of The Square ........................................................19 days are about celebs going on a ‘life journey,’ SPECIAL REPORT cryin’ at the end of it… SCIENCE FOCUS An exploration of four scintillating science-based projects .................24 This is not that sort of FORMAT FOCUS program.” 30 Syfy going live with Opposite Worlds ..................................................28 AND ONE MORE THING NOVEMBERNOVEMBER / DECEMBER 1313 on the cover F***in’ hell, it’s Karl Pilkington! .........................................................30 Design fi rm MK12 collaborated with SCIENCE the fi lmmakers of the feature doc IN FOCUS Particle Fever to help explain particle How the Particle Fever team made a physics thriller theory via stunning animations. -

Th' Abstract of All Faults: Antony Vs. the Hegemonic

Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, Vol. 3, No. 1 (2010) ARTICLE Th’ Abstract of All Faults: Antony vs. the Hegemonic Man RACHAEL KELLY, UNIVERSITY OF ULSTER ABSTRACT The story of the lives and deaths of Cleopatra VII of Egypt and her lover, the Roman triumvir Marcus Antonius, have been the subject of considerable mythologisation in the two millennia since their suicides at Alexandria. In recent years, some scholars have noted that the image of Cleopatra has been used, in various texts, to perform cultural anxieties about the meaning of acceptable womanhood. However, whilst there is some evidence (albeit problematic) that the screen Cleopatras of the past forty years have been subject to a recuperation of sorts, there has been no similar recuperation or critical analysis of the image of Antonius (or Antony). This paper seeks to examine the use of Antony to interrogate notions of hegemonic masculinity on screen, through an analysis of five texts covering the years 1934-2007 which feature Antony in a key role. By investigating the opposition of Antony and his performance of deficient masculinity against the recurring figure of the paradigm or hegemonic man, this paper seeks to position Antony as a site for the negotiation and articulation of anxieties about the performance of idealised masculinity. KEY WORDS Mark Antony, gender performance, historical films, hegemonic masculinity If bodies in perspective space appear to be ranged along a continuum from closer to father away, might there not be an equivalent continuum in psychic space? To understand masculinity in terms of others, we need to consider two distinct situations: one in which masculinity is defined vis-à-vis various opposites and one in which masculinity is experienced as a kind of merging or fusion of self with others. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room.