Illuminations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Front Page First Opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, It Was Instantly Heralded As a Classic

SUPPORT FOR THE 2019 SEASON OF THE FESTIVAL THEATRE IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY DANIEL BERNSTEIN AND CLAIRE FOERSTER PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY NONA MACDONALD HEASLIP 2 DIRECTOR’S NOTES SCAVENGING FOR THE TRUTH BY GRAHAM ABBEY “Were it left to me to decide between a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.” – Thomas Jefferson, 1787 When The Front Page first opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, it was instantly heralded as a classic. Nearly a century later, this iconic play has retained its place as one of the great American stage comedies of all time. Its lasting legacy stands as a testament to its unique DNA: part farce, part melodrama, with a healthy dose of romance thrown into the mix, The Front Page is at once a veneration and a reproof of the gritty, seductive world of Chicago journalism, firmly embedded in the freewheeling euphoria of the Roaring Twenties. According to playwrights (and former Chicago reporters) Charles MacArthur and Ben Hecht, the play allegedly found its genesis in two real-life events: a practical joke carried out on MacArthur as he was heading west on a train with his fiancée, and the escape and disappearance of the notorious gangster “Terrible” Tommy consuming the conflicted heart of a city O’Conner four days before his scheduled caught in the momentum of progress while execution at the Cook County Jail. celebrating the underdogs who were lost in its wake. O’Conner’s escape proved to be a seminal moment in the history of a city struggling Chicago’s metamorphosis through the to find its identity amidst the social, cultural “twisted twenties” is a paradox in and of and industrial renaissance of the 1920s. -

Mar Customer Order Form

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18MAR 2013 MAR COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Mar Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 3:35:28 PM Available only STAR WARS: “BOBA FETT CHEST from your local HOLE” BLACK T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! MACHINE MAN THE WALKING DEAD: ADVENTURE TIME: CHARCOAL T-SHIRT “KEEP CALM AND CALL “ZOMBIE TIME” Preorder now! MICHONNE” BLACK T-SHIRT BLACK HOODIE Preorder now! Preorder now! 3 March 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 2/7/2013 10:05:45 AM X #1 kiNG CoNaN: Dark Horse ComiCs HoUr oF THe DraGoN #1 Dark Horse ComiCs GreeN Team #1 DC ComiCs THe moVemeNT #1 DoomsDaY.1 #1 DC ComiCs iDW PUBlisHiNG THe BoUNCe #1 imaGe ComiCs TeN GraND #1 UlTimaTe ComiCs imaGe ComiCs sPiDer-maN #23 marVel ComiCs Mar13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 2:21:38 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 2 #1 l ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT Uber #1 l AVATAR PRESS Suicide Risk #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Clive Barker’s New Genesis #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Marble Season HC l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Black Bat #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 1 Battlestar Galactica #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Grimm #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Wars In Toyland HC l ONI PRESS INC. The From Hell Companion SC l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Valiant Masters: Shadowman Volume 1: The Spirits Within HC l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Rurouni Kenshin Restoration Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Soul Eater Soul Art l YEN PRESS BOOKS & MAGAZINES 2 Doctor Who: Who-Ology Official Miscellany HC l DOCTOR WHO / TORCHWOOD Doctor Who: The Official -

Download Book \ Rurouni Kenshin: V. 10 # 5HB0XPJPHEM9

A9XS6AAGYUEB \ Book # Rurouni Kenshin: v. 10 Rurouni Kenshin: v. 10 Filesize: 7.83 MB Reviews Completely among the finest ebook We have at any time read through. it was actually writtern really properly and helpful. You are going to like just how the writer compose this publication. (Mr. Deangelo Considine) DISCLAIMER | DMCA TRMZY0UNH8QK ^ Kindle Rurouni Kenshin: v. 10 RUROUNI KENSHIN: V. 10 To get Rurouni Kenshin: v. 10 eBook, make sure you access the hyperlink below and download the document or gain access to other information which are have conjunction with RUROUNI KENSHIN: V. 10 ebook. Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc. Paperback. Book Condition: new. BRAND NEW, Rurouni Kenshin: v. 10, Nobuhiro Watsuki, Packed with action, romance and historical intrigue, "Rurouni Kenshin" is one of the most beloved and popular manga series worldwide. Set against the backdrop of the Meiji Restoration, it tells the saga of Himura Kenshin, once an assassin of ferocious power, now a humble "rurouni," a wandering swordsman fighting to protect the honor of those in need. A hundred and fiy years ago in Kyoto, amid the flames of revolution, there arose a warrior, an assassin of such ferocious power he was given the title "Hitokiri" Manslayer. With his bloodstained blade, Hitokiri Battosai helped close the turbulent Bakumatsu period and end the reign of the shoguns, slashing open the way toward the progressive Meiji Era. Then he vanished, and with the flow of years became legend. In the 11th year of Meiji, in the middle of Tokyo, the tale begins. Himura Kenshin, a humble "rurouni," or wandering swordsman, comes to the aid of Kamiya Kaoru, a young woman struggling to defend her father's school of swordsmanship against attacks by the infamous Hitokiri Battosai. -

Downloads, and Weekly Attendees

riscilla apersVol 32, No 4 | Autumn 2018 PPThe academic journal of CBE International Social Sciences 3 Muted Group Theory: A Tool for Hearing Marginalized Voices Linda Lee Smith Barkman 8 The Importance of Age Norms When Considering Gender Issues Jason Eden and Naomi Eden 14 Christian Women’s Beliefs on Female Subordination and Male Authority Susan H. Howell and Kristyn Duncan 15 The Experiences of Women in Church and Denominational Leadership Susan H. Howell and Ariel Thompson 18 Marriage Ideology and Decision-Making Susan H. Howell, Bethany G. Lester, Alayna N. Owens 23 The Delight of Daughters: A Theology of Daughterhood Beulah Wood 29 Book Review: Biblical Porn: Affect, Labor, and Pastor Mark Driscoll’s Evangelical Empire by Jessica Johnson Jamin Hübner Priscilla and Aquila instructed Apollos more perfectly in the way of the Lord. (Acts 18:26) I Tertius . that made you fight to stay awake. It was the art (or lack thereof) of communication, which is a social science. Psychology and sociology, ethnography Consider counseling, a profession and skill set which and ethnology, political science and arises primarily from psychology. A Christian counselor economics. These and other social will approach psychology, and therefore counseling, with sciences are tools for understanding a certain set of theological beliefs. To give a final example, the people of the world—as individuals, Bible translation—surely an endeavor that underlies almost as families, as groups, as cultures and all biblical interpretation—happens at the intersection of subcultures. The articles in this issue of biblical studies and human language. And, of course, the Priscilla Papers all arise, directly or indirectly, from one or study of language (linguistics) and of the cultures that more social sciences. -

Spotted.Yankton.Net...Upload & Share Your Photos for FREE...Purchase

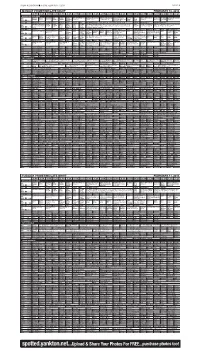

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 7, 2014 PAGE 9B MONDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT FEBRUARY 10, 2014 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Curious Arthur Å WordGirl Wild Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow Independent Lens The Red BBC Charlie Rose (N) (In Tavis Smi- The Mind Antiques Roadshow PBS George (DVS) Å (DVS) Kratts Å Speaks Business Stereo) Å “Detroit” (N) Å “Eugene, OR” Å Mississippi agency and Green World Stereo) Å ley (N) Å of a Chef “Detroit” Å KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report civil rights. (N) Show News Å KTIV $ 4 $ XXII Olympics Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent XXII Winter Olympics Alpine Skiing, Freestyle Skiing, Short Track. Å News 4 XXII Olympics XXII Winter Olympics XXII Winter Olympics Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big XXII Winter Olympics Alpine Skiing, Freestyle Skiing, Short Track. From Sochi, KDLT XXII Winter Olympics XXII Winter Olympics Alpine Skiing, Freestyle NBC Speed Skating, Biath- Judy Å Judy Å News Nightly News Bang Russia. Alpine skiing: women’s super combined; freestyle skiing; short track. (N News Å Short Track, Luge. Å Skiing, Short Track. (In Stereo) Å KDLT % 5 % lon. Å (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory Same-day Tape) (In Stereo) Å KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. Phil Å The Dr. Oz Show News at ABC News Inside The Bachelor (N) (In Stereo) Å Castle “Valkyrie” News Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline Paid Inside ABC World News Dr. -

SBR Media Catalog of Works Genre: Romance

SBR Media Catalog of Works Genre: Romance This catalog features the novels available for foreign translation and audio rights purchases. SBR Media is owned by Stephanie Phillips Contact: [email protected] Phone: 843.421.7570 SBR Media 3761 Renee Dr. Suite #223 Myrtle Beach, SC 29526 The information in this catalog is accurate as of July 29, 2020. Clients, titles, and availability should be confirmed. SBR Media Catalog of Works .................................................................................................................... 1 Alexis Noelle ............................................................................................................................................... 14 Her Series : Contemporary Suspense ...................................................................................................... 14 Keeping Her ......................................................................................................................................... 14 Deathstalkers MC Series : Contemporary Suspense ............................................................................... 15 Corrupted ............................................................................................................................................. 15 Shattered Series : Contemporary Suspense ............................................................................................. 15 Shattered Innocence ............................................................................................................................ -

Aniplex to Release Rurouni Kenshin Ovas and Movie on Blu-Ray Simultaneously with Japan

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 28, 2011 Aniplex to Release Rurouni Kenshin OVAs and Movie on Blu-ray Simultaneously with Japan © N. Watsuki / Shueisha, Fuji-TV, Aniplex Inc. SANTA MONICA, CA (May 28, 2011) – Celebrating the 15th anniversary of the hit series-turned-international anime franchise Rurouni Kenshin, Aniplex of America Inc. announced today that it will be releasing the Blu-ray disc versions of the OVA (Original Video Animation) series and movie in North America, through RightStuf.com and Bandai Entertainment’s The Store on the same day as Japan. A total of three BD releases is scheduled to launch on the following dates: Rurouni Kenshin: Trust & Betrayal – August 24 Rurouni Kenshin: Reflection – September 21 Rurouni Kenshin The Movie – October 26 Aniplex of America will import the Japanese editions of the Blu-ray discs, with each release sporting exclusive packaging that features new illustration artwork by Rurouni Kenshin OVA animation director/animator Atsuko Nakajima (Trinity Blood, Ranma ½, You’re Under Arrest!), along with the inclusion of an English translated booklet. Each Blu-ray release (digitally remastered and includes both the English and Japanese audio with English subtitles), will be distributed in limited quantities and sold through while supplies last. With the 15th Anniversary already underway, Aniplex also plans to develop a new Rurouni Kenshin project, with additional details to follow as soon as they become available. “Those of you who follow and love the story of Kenshin will most likely enjoy this movie immensely, and you will definitely be moved by its tissue invoking emotion” – David Blair / DvdTalk.com “The artwork for the series is amazing” – AnimeNewsNetwork.com “No matter what kind of anime you watch, you will benefit from watching this series.”– AnimeNewsNetwork.com “…there’s enough action to satisfy even the most testosterone-laden anime fan. -

Anime Publisher Year a Tree of Palme ADV Films 2005 Abenobashi ADV

Anime Publisher Year A Tree of Palme ADV Films 2005 Abenobashi ADV Films 2005 Ah! My Goddess Pioneer 2000 Air Gear ADV Films 2007 Akira Pioneer 1994 Alien Nine US Manga 2003 Android Kikaider Bandai Entertainment 2002 Angelic Layer ADV Films 2005 Aquarian Age ADV Films 2005 Arjuna Bandai Entertainment 2001 Black Cat Funimation 2005 Black Heaven Pioneer 1999 Black Lagoon Funimation 2006 Blood: The Last Vampire Manga Entertainment 2001 Blood+ Sony Pictures 2005 BoogiePop Phantom NTSC 2001 Brigadoon Tokyo Pop 2003 C Control Funimation 2011 Ceres: Celestial Legend VIS Media 2000 Chevalier D'Eon Funimation 2006 Cowboy Bebop Bandai Entertainment 1998 Cromartie High Scool ADV Films 2006 Dai-Guard ADV Films 1999 Dears Bandai Visual 2004 DeathNote VIS Media 2003 Elfen Lied ADV Films 2006 Escaflowne Bandai Entertainment 1996 Fate Stay/Night TBS Animation 2013 FLCL Funimation 2000 Fruits Basket Funimation 2002 Full Metal Achemist: Brotherhood Funimation 2010 Full Metal Alchemist Funimation 2004 Full Metal Panic? ADV Films 2004 G Gundam Bandai Entertainment 1994 Gankutsuou Gnzo Media Factory 2004 Gantz ADV Films 2004 Geneshaft Bandai Entertainment 2001 Getbackers ADV Films 2005 Ghost in the Shell Bandai Entertainment 2002 Ghost Stories ADV Films 2000 Grave of the Fireflies Central Pak Media 1988 GTO Great Teacher Onizuka Tokyo Pop 2004 Gungrave Pioneer 2004 Gunslinger Girl Funimation 2002 Gurren Lagann Bandai Entertainment 2007 Guyver ADV Films 2007 Heat Guy J Pioneer 2002 Hellsing Pioneer 2002 Infinite Ryvius Bandai Entertainment 1999 Jin-Roh Bandai -

Animal Traffic: Making, Remaking, and Unmaking Commodities in Global Live Wildlife Trade

ANIMAL TRAFFIC: MAKING, REMAKING, AND UNMAKING COMMODITIES IN GLOBAL LIVE WILDLIFE TRADE by ROSEMARY-CLAIRE MAGDELEINE SOLANGE COLLARD A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Geography) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Rosemary-Claire Magdeleine Solange Collard, 2013 Abstract Against mass species loss and escalating concern over declining biodiversity, legal and illegal trade in wildlife is booming. Annually, it generates tens of billions of dollars and involves the circulation of billions of live and dead animals worldwide. This dissertation examines one dimension of this economy: flows of live, wild-caught animals – namely exotic pets – into North America. My central questions are: how are wild animals’ lives and bodies transformed into commodities that circulate worldwide and can be bought and owned? How are these commodities remade and even unmade? In answering these questions the dissertation is concerned not only with embodied practices, but also with broader, dominant assumptions about particular figures of the human and the animal, and the relations between them. This dissertation draws on reading across economic geography and sociology, political economy and ecology, and political theory to construct a theoretical approach with three strands: a commodity chain framework, a theory of performativity, and an anti-speciesist position. It weaves this theoretical grounding through multi-sited -

Manga Vision: Cultural and Communicative Perspectives / Editors: Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou, Cathy Sell; Queenie Chan, Manga Artist

VISION CULTURAL AND COMMUNICATIVE PERSPECTIVES WITH MANGA ARTIST QUEENIE CHAN EDITED BY SARAH PASFIELD-NEOFITOU AND CATHY SELL MANGA VISION MANGA VISION Cultural and Communicative Perspectives EDITED BY SARAH PASFIELD-NEOFITOU AND CATHY SELL WITH MANGA ARTIST QUEENIE CHAN © Copyright 2016 Copyright of this collection in its entirety is held by Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou and Cathy Sell. Copyright of manga artwork is held by Queenie Chan, unless another artist is explicitly stated as its creator in which case it is held by that artist. Copyright of the individual chapters is held by the respective author(s). All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/mv-9781925377064.html Series: Cultural Studies Design: Les Thomas Cover image: Queenie Chan National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: Manga vision: cultural and communicative perspectives / editors: Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou, Cathy Sell; Queenie Chan, manga artist. ISBN: 9781925377064 (paperback) 9781925377071 (epdf) 9781925377361 (epub) Subjects: Comic books, strips, etc.--Social aspects--Japan. Comic books, strips, etc.--Social aspects. Comic books, strips, etc., in art. Comic books, strips, etc., in education. -

Aniplex Books R.O.D -THE COMPLETE- Blu-Ray BOX for Distribution This Winter Through Bandai and Right Stuf

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 7th, 2010 Aniplex books R.O.D -THE COMPLETE- Blu-ray BOX for distribution this winter through Bandai and Right Stuf © 2001, 2002 Studio Orphee / Aniplex © Studio Orphee / Aniplex SANTA MONICA, CA (October 7, 2010) – Aniplex of America Inc. announced today that R.O.D READ OR DIE -THE COMPLETE- Blu-ray BOX—recently licensed for distribution in North America—will be released January 18th, 2011 through Bandai Entertainment, Inc.’s ―The Store‖ online retail shop and RightStuf.com. In addition, both companies have signed on to distribute Aniplex’s Durarara!! DVDs. Previously released on standard DVD format in North America, both R.O.D -READ OR DIE- OVA series and R.O.D -THE TV- have garnered critical acclaim and a groundswell of support from many anime enthusiasts over the years. Now, with the gradual consumer shift over to high definition Blu-ray players and matching video software, R.O.D -THE COMPLETE- Blu-ray BOX becomes Aniplex’s first official BD release in North America. “…perfect anime fun.” – AintItCool.com “A well put together show that grows better with each episode.” – DVDTalk.com “…R.O.D the TV does not disappoint. This is an action series with intelligence and wit…” – DVDVerdict.com “Mania Grade: A+ R.O.D is a series that has great replay value once it’s finished since it makes you go back to the OVA release and then soak it all in again to see all the little bits that you missed the first time around.” – Chris Beveridge / Mania.com R.O.D -THE COMPLETE- Blu-ray Box includes: ALL 29 episodes on 5 discs: -

2013 Japan Film Festival of San Francisco General

Media Contact: Erik Jansen MediaLab [email protected] (714) 620-5017 PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: JAPAN FILM FESTIVAL OF SAN FRANCISCO LAUNCHES JULY 27th TO OFFER BAY AREA SCREENINGS OF THE BEST IN RECENT JAPANESE LIVE-ACTION AND ANIME CINEMA More Than 15 Titles To Premiere At NEW PEOPLE Cinema In A Special Week-Long Film Festival Set To Launch In Conjunction With The 2013 J-POP Summit San Francisco, CA, July 11, 2013 – The Japan Film Festival of San Francisco, the first fully- dedicated annual Japanese film celebration for the S.F. Bay Area, will launch in just a couple of weeks at NEW PEOPLE Cinema, San Francisco’s famed pop culture movie theatre located inside of the NEW PEOPLE J-Pop entertainment complex in the heart of the city’s Japantown. Kicking off on Saturday, July 27th, in conjunction with the 2013 J-POP Summit Festival, and running thru Sunday, August 4th, the Japan Film Festival of San Francisco (JFFSF) is the first fully-dedicated annual Japanese film event for the S.F. Bay Area and will screen more than 15 acclaimed live-action and anime films representing some of the best in recent Japanese cinema. Several notable Guests of Honor, including directors Miwa Nishikawa (Dreams for Sale) and Shinsuke Sato (GANTZ, Library Wars), as well artist “Zero Yen” architect Kyohei Sakaguchi will also appear in-person for the premieres of their latest projects. Tickets are $13.00 per film. NEW PEOPLE Cinema is located in San Francisco’s Japantown at 1746 Post St. (Cross St.